Trapezoidal rule

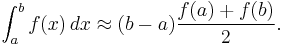

In numerical analysis, the trapezoidal rule (also known as the trapezoid rule or trapezium rule) is an approximate technique for calculating the definite integral

The trapezoidal rule works by approximating the region under the graph of the function  as a trapezoid and calculating its area. It follows that

as a trapezoid and calculating its area. It follows that

Contents |

Applicability and alternatives

The trapezoidal rule is one of a family of formulas for numerical integration called Newton–Cotes formulas, of which the midpoint rule is similar to the trapezoid rule. Simpson's rule is another member of the same family, and in general has faster convergence than the trapezoidal rule for functions which are twice continuously differentiable, though not in all specific cases. However for various classes of rougher functions (ones with weaker smoothness conditions), the trapezoidal rule has faster convergence in general than Simpson's rule.[1]

Moreover, the trapezoidal rule tends to become extremely accurate when periodic functions are integrated over their periods, which can be analyzed in various ways.[2][3]

For non-periodic functions, however, methods with unequally spaced points such as Gaussian quadrature and Clenshaw–Curtis quadrature are generally far more accurate; Clenshaw–Curtis quadrature can be viewed as a change of variables to express arbitrary integrals in terms of periodic integrals, at which point the trapezoidal rule can be applied accurately.

Numerical Implementation

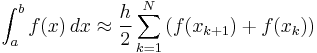

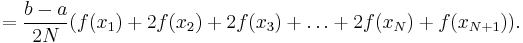

Uniform Grid

For a domain discretized into "N" equally spaced panels, or "N+1" grid points (1, 2, ..., N+1), where the grid spacing is "h=(b-a)/N", the approximation to the integral becomes

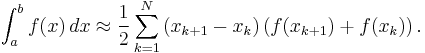

Non-uniform Grid

When the grid spacing is non-uniform, one can use the formula

Error analysis

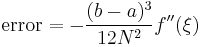

The error of the composite trapezoidal rule is the difference between the value of the integral and the numerical result:

There exists a number ξ between a and b, such that[4]

It follows that if the integrand is concave up (and thus has a positive second derivative), then the error is negative and the trapezoidal rule overestimates the true value. This can also be seen from the geometric picture: the trapezoids include all of the area under the curve and extend over it. Similarly, a concave-down function yields an underestimate because area is unaccounted for under the curve, but none is counted above. If the interval of the integral being approximated includes an inflection point, then the error is harder to identify.

In general, three techniques are used in the analysis of error:[5]

An asymptotic error estimate for N → ∞ is given by

Further terms in this error estimate are given by the Euler–Maclaurin summation formula.

It is argued that the speed of convergence of the trapezoidal rule reflects and can be used as a definition of classes of smoothness of the functions.[2]

Periodic functions

The trapezoidal rule often converges very quickly for periodic functions.[3] This can be explained intuitively as:

- "When the function is periodic and one integrates over one full period, there are about as many sections of the graph that are concave up as concave down, so the errors cancel."[5]

More detailed analysis can be found in.[2][3]

"Rough" functions

For various classes of functions that are not twice-differentiable, the trapezoidal rule has sharper bounds than Simpson's rule.[1]

Sample implementations

Excel

The trapezoidal rule is easily implemented in Excel.

As an example, we show the integral of  .

.

Python

The (composite) trapezoidal rule can be implemented in Python as follows:

#!/usr/bin/env python def trapezoidal_rule(f, a, b, N): """Approximate the definite integral of f from a to b by the composite trapezoidal rule, using N subintervals""" return (b-a) * ( f(a)/2 + f(b)/2 + sum([f(a + (b-a)*k/N) for k in xrange(1,N)]) ) / N print trapezoidal_rule(lambda x:x**9, 0.0, 10.0, 100000) # displays 1000000000.75

MATLAB and GNU Octave

The (composite) trapezoidal rule can be implemented in MATLAB as follows:

function [F] = trap(f,a,b,n) %% f=name of function, a=start value, b=end value, n=number of intervals h = (b - a) / n; x = [a:h:b]; for ii = 1: length(x) y(ii) = f(x(ii)); end F = h*(y(1) + 2*sum(y(2:end-1)) + y(end))/2; end

This method is also built-in to MATLAB under the function name trapz.

C++

In C++, one can implement the trapezoidal rule as follows.

template <class ContainerA, class ContainerB> double trapezoid_integrate(const ContainerA &x, const ContainerB &y) { if (x.size() != y.size()) { throw std::logic_error("x and y must be the same size"); } double sum = 0.0; for (int i = 1; i < x.size(); i++) { sum += (x[i] - x[i-1]) * (y[i] + y[i-1]); } return sum * 0.5; }

Here, x and y can be any object of a class implementing operator[] and size().

See also

- Rectangle method

- Simpson's rule

- Romberg's method

- Newton–Cotes formulas

- Gaussian quadrature

- Tai's method (a rediscovery of the trapezoidal rule)

Notes

- ^ a b (Cruz-Uribe & Neugebauer 2002)

- ^ a b c (Rahman & Schmeisser 1990)

- ^ a b c (Weideman 2002)

- ^ Atkinson (1989, equation (5.1.7))

- ^ a b (Weideman 2002, p. 23, section 2)

- ^ Atkinson (1989, equation (5.1.9))

- ^ Atkinson (1989, p. 285)

References

- Atkinson, Kendall E. (1989), An Introduction to Numerical Analysis (2nd ed.), New York: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-471-50023-0.

- Rahman, Qazi I.; Schmeisser, Gerhard (December 1990), "Characterization of the speed of convergence of the trapezoidal rule", Numerische Mathematik 57 (1): 123–138, doi:10.1007/BF01386402, ISSN 0945-3245

- Burden, Richard L.; J. Douglas Faires (2000), Numerical Analysis (7th ed.), Brooks/Cole, ISBN 0-534-38216-9.

- Weideman, J. A. C. (January 2002), "Numerical Integration of Periodic Functions: A Few Examples", The American Mathematical Monthly 109 (1): 21–36, doi:10.2307/2695765, JSTOR 2695765

- Cruz-Uribe, D.; Neugebauer, C.J. (2002), "Sharp Error Bounds for the Trapezoidal Rule and Simpson's Rule", Journal of Inequalities in Pure and Applied Mathematics 3 (4), http://www.emis.de/journals/JIPAM/images/031_02_JIPAM/031_02.pdf

External links

- Trapezoidal Rule for Numerical Integration

- Notes on the convergence of trapezoidal-rule quadrature

- Trapezoidal Rule of Integration – Notes, PPT, Videos, Mathcad, Matlab, Mathematica, Maple, Multiple Choice Tests at Holistic Numerical Methods Institute

- C Language Implementation of Trapezoidal Rule

![\text{error} = \int_a^b f(x)\,dx - \frac{b-a}{N} \left[ {f(a) %2B f(b) \over 2} %2B \sum_{k=1}^{N-1} f \left( a%2Bk \frac{b-a}{N} \right) \right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/fcc7b80f5e85dce8b8a262ee9ce83223.png)

![\text{error} = -\frac{(b-a)^2}{12N^2} \big[ f'(b)-f'(a) \big] %2B O(N^{-3}).](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/1b56d173d86d901046ad0eef1308513e.png)