Traffic congestion: Reconstruction with Kerner's three-phase theory

Vehicular traffic can be either free or congested. Traffic occurs in time and space, i.e., it is a spatiotemporal process. However, usually traffic can be measured only at some road locations (for example, via road detectors, video-cameras, probe vehicle data, or phone data). For efficient traffic control and other intelligent transportation systems, the reconstruction of traffic congestion is necessary at all other road locations at which traffic measurements are not available. Traffic congestion can be reconstructed in space and time (Fig. 1) based on Boris Kerner’s three-phase traffic theory with the use of the ASDA and FOTO models introduced by Kerner[1][2][3][4][5]. Kerner’s three-phase traffic theory and, respectively, the ASDA/FOTO models are based on some common spatiotemporal features of traffic congestion observed in measured traffic data.

Common spatiotemporal empirical features of traffic congestion

Definition

Common spatiotemporal empirical features of traffic congestion are those spatiotemporal features of traffic congestion, which are qualitatively the same for different highways in different countries measured during years of traffic observations. In particular, common features of traffic congestion are independent on weather, road conditions and road infrastructure, vehicular technology, driver characteristics, day time, etc.

Kerner’s definitions [S] and [J], respectively, for the synchronized flow and wide moving jam phases in congested traffic[6][7][8] are examples of common spatiotemporal empirical features of traffic congestion.

Propagation of wide moving jams through highway bottlenecks

In empirical observations, traffic congestion occurs usually at a highway bottleneck as a result of traffic breakdown in an initially free flow at the bottleneck. A highway bottleneck can result from on- and off-ramps, road curves and gradients, road works, etc.

In congested traffic (this is a synonym term to traffic congestion), a phenomenon of the propagation of a moving traffic jam (moving jam for short) is often observed. A moving jam is a local region of low speed and great density that propagates upstream as a whole localized structure. The jam is limited spatially by two jam fronts. At the downstream jam front, vehicles accelerate to a higher speed downstream of the jam. At the upstream jam front, vehicles decelerate while approaching the jam.

A wide moving jam is a moving jam that exhibits the characteristic jam feature [J], which is a common spatiotemporal empirical feature of traffic congestion. The jam feature [J] defines the wide moving jam traffic phase in congested traffic as follows.

Definition [J] for wide moving jam

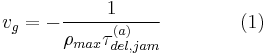

A wide moving jam is a moving traffic jam, which exhibits the characteristic jam feature [J] to propagate through any bottlenecks while maintaining the mean velocity of the downstream jam front denoted by  .

.

Kerner’s jam feature [J] can be explained as follows. The motion of the downstream jam front results from acceleration of drivers from a standstill within the jam to traffic flow downstream of the jam. After a vehicle has begun to accelerate escaping from the jam, to satisfy safety driving, the following vehicle begins to accelerate with a time delay. We denote the mean value of this time delay in vehicle acceleration at the downstream jam front by  . Because the average distance between vehicles within the jam, including average vehicle length, equals to

. Because the average distance between vehicles within the jam, including average vehicle length, equals to  (where

(where  is the average vehicle density within the jam), the mean velocity of the downstream jam front

is the average vehicle density within the jam), the mean velocity of the downstream jam front  is

is

.

.

When traffic parameters (percentage of long vehicles, weather, driver characteristics, etc.) do not change over time,  and

and  are constant in time. This explains why the mean velocity of the downstream jam front

are constant in time. This explains why the mean velocity of the downstream jam front  (1) is the characteristic parameter that does not depend of the flow rates and densities upstream and downstream of the jam.

(1) is the characteristic parameter that does not depend of the flow rates and densities upstream and downstream of the jam.

Catch effect: pinning of downstream front of synchronized flow at bottleneck

In contrast with the jam feature [J], the mean velocity of the downstream front of synchronized flow is not self-maintained during the front propagation. This is the common feature of synchronized flow that is one of the two phases of traffic congestion.

A particular case of this common feature of synchronized flow is that the downstream synchronized flow front is usually caught at a highway bottleneck. This pinning of the downstream front of synchronized flow at the bottleneck is called the catch effect. Note that at this downstream front of synchronized flow, vehicles accelerate from a lower speed within synchronized flow upstream of the front to a higher speed in free flow downstream of the front.

Definition [S] for synchronized flow

Synchronized flow is defined as congested traffic that does not exhibit the jam feature [J]; in particular, the downstream front of synchronized flow is often fixed at the bottleneck.

Thus Kerner’s definitions [J] and [S] for the wide moving jam and synchronized flow phases of his three-phase traffic theory[6][7][8] are indeed associated with common empirical features of traffic congestion.

Empirical example of wide moving jam and synchronized flow

Vehicle speeds measured with road detectors (1 min averaged data) illustrate Kerner’s definitions [J] and [S] (Fig. 2 (a, b)). There are two spatiotemporal patterns of congested traffic with low vehicle speeds in Fig. 2 (a). One pattern of congested traffic propagates upstream with almost constant mean velocity of the downstream pattern front through the freeway bottleneck. According to the definition [J] this pattern of congested traffic belongs to the "wide moving jam" traffic phase. In contrast, the downstream front of the other pattern of the congested traffic is fixed at the bottleneck. According to the definition [S] this pattern of congested traffic belongs to the "synchronized flow" traffic phase (Fig. 2 (a) and (b)).

ASDA and FOTO models

The FOTO (Forecasting of traffic objects) model reconstructs and tracks regions of synchronized flow in space and time. The ASDA (Automatische Staudynamikanalyse: Automatic Tracking of Moving Jams) model reconstructs and tracks wide moving jams. The ASDA/FOTO models are devoted to on-line applications without calibration of model parameters under different environment conditions, road infrastructure, percentage of long vehicles, etc.

General features

Firstly, the ASDA/FOTO models identify the synchronized flow and wide moving jam phases in measured data of congested traffic. One of the empirical features the synchronized flow and wide moving jam phases used in the ASDA/FOTO models for traffic phase identification is as follows: Within a wide moving jam, both the speed and flow rate are very small (Fig. 2 (c-f)). In contrast, whereas the speed with the synchronized flow phase is considerably lower than in free flow (Fig. 2 (c, e)), the flow rate in synchronized flow can be as great as in free flow (Fig. 2 (d, f)).

Secondly, based on the abovementioned common features of wide moving jams and synchronized flow, the FOTO model tracks the downstream and upstream fronts of synchronized flow denoted by  ,

,  , where

, where  is time (Fig. 3). The ADSA model tracks the downstream and upstream fronts of wide moving jams denoted by

is time (Fig. 3). The ADSA model tracks the downstream and upstream fronts of wide moving jams denoted by  ,

,  (Fig. 3). This tracking is carried out between road locations at which the traffic phases have initially been identified in measured data, i.e., when synchronized flow and wide moving jams cannot be measured.

(Fig. 3). This tracking is carried out between road locations at which the traffic phases have initially been identified in measured data, i.e., when synchronized flow and wide moving jams cannot be measured.

In other words, the tracking of synchronized flow by the FOTO model and wide moving jams by the ASDA model is performed at road locations at which no traffic measurements are available, i.e., the ASDA/FOTO models make the forecasting of the front locations of the traffic phases in time. The ASDA/FOTO models enable us to predict the merging and/or the dissolution of one or more initially different synchronized flow regions and of one or more initially different wide moving jams that occur between measurement locations.

ASDA/FOTO models for data measured by road detectors

Cumulative flow approach for FOTO

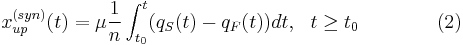

While the downstream front of synchronized flow at which vehicles accelerate to free flow is usually fixed at the bottleneck (see Fig. 2 (a, b)), the upstream front of synchronized flow at which vehicles moving initially in free flow must decelerate approaching synchronized flow can propagate upstream. In empirical (i.e., measured) traffic data, the velocity of the upstream front of synchronized flow depends usually considerably both on traffic variables within synchronized flow downstream of the front and within free flow just upstream of this front. A good correspondence with empirical data is achieved, if a time-dependence of the location of the synchronized flow front is calculated by the FOTO model with the use of a so-called cumulative flow approach:

where  and

and  [vehicles/h] are respectively the flow rates upstream and downstream of the synchronized flow front,

[vehicles/h] are respectively the flow rates upstream and downstream of the synchronized flow front,  is a model parameter [m/vehicles], and

is a model parameter [m/vehicles], and  is the number of road lanes.

is the number of road lanes.

Two approaches for jam tracking with ASDA

There are two main approaches for the tracking of wide moving jams with the ASDA model:

- The use of the Stokes-shock-wave formula.

- The use of a characteristic velocity of wide moving jams.

The use of the Stokes-shock-wave formula in ASDA

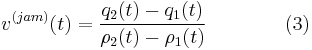

The current velocity  of a front of a wide moving jam is calculated though the use of the shock-wave formula derived by Stokes in 1848[9]:

of a front of a wide moving jam is calculated though the use of the shock-wave formula derived by Stokes in 1848[9]:

,

,

where  and

and  the flow rate and density upstream of the jam front that velocity should be found;

the flow rate and density upstream of the jam front that velocity should be found;  and

and  are the flow rate and density downstream of this jam front. In (3) no any relationship, in particular, no fundamental diagram is used between the flow rates

are the flow rate and density downstream of this jam front. In (3) no any relationship, in particular, no fundamental diagram is used between the flow rates  ,

,  and vehicle densities

and vehicle densities  ,

,  found from measured data independent of each other.

found from measured data independent of each other.

The use of a characteristic velocity of wide moving jams

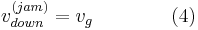

If measured data are not available for the tracking of the downstream jam front with the Stokes-shock-wave formula (3), the formula

is used in which  is the characteristic velocity of the downstream jam front associated with Kerner’s jam feature [J] discussed above. This means that after the downstream front of a wide moving jam has been identified at a time instant

is the characteristic velocity of the downstream jam front associated with Kerner’s jam feature [J] discussed above. This means that after the downstream front of a wide moving jam has been identified at a time instant  , the location of the downstream front of the jam can be estimated with formula

, the location of the downstream front of the jam can be estimated with formula

The characteristic jam velocity is illustrated in Fig. 4. Two wide moving jams propagate upstream while maintaining the mean velocity of their downstream fronts. There are two jams following each other in this empirical example.

However, in contrast with the mean velocity of the downstream jam front, the mean velocity of the upstream jam front depends on the flow rate and density in traffic flow upstream of the jam. Therefore, in a general case the use of formula (5) can lead to a great error by the estimation of the mean velocity of the upstream jam front.

In many data measured on German highways has been found  . However, although the mean velocity

. However, although the mean velocity  of the downstream jam front is independent of the flow rates and densities upstream and downstream of the jam,

of the downstream jam front is independent of the flow rates and densities upstream and downstream of the jam,  can depend considerably on traffic parameters like the percentage of long vehicles in traffic, weather, driver characteristics, etc. As a result, the mean velocity

can depend considerably on traffic parameters like the percentage of long vehicles in traffic, weather, driver characteristics, etc. As a result, the mean velocity  found in different data measured over years of observations varies approximately within the range

found in different data measured over years of observations varies approximately within the range  .

.

On-line applications of ASDA/FOTO models in traffic control centres

Reconstruction and tracking of spatiotemporal congested patterns with the ASDA/FOTO models is done today online permanently in the traffic control centre of the federal state Hessen (Germany) for 1200 km of freeway network. Since April 2004 measured data of nearly 2500 detectors are automatically analyzed by ASDA/FOTO. The resulting spatiotemporal traffic patterns are illustrated in a space-time diagram showing congested pattern features like Fig. 5. The online system has also been installed in 2007 for North-Rhine Westphalia freeways. The raw traffic data are transferred to WDR, the major public radio broadcasting station from North-Rhine Westphalia in Cologne, who offers traffic messages to the end customer (e. g., radio listener or driver) via broadcast channel RDS. The application covers a part of the whole freeway network with 1900 km of freeway and more than 1000 double loop detectors. In addition, since 2009 ASDA/FOTO models are online in the northern part of Bavaria.

Average traffic flow characteristics and travel time

In addition to spatiotemporal reconstruction of traffic congestion (Figs. 1 and 5), the ASDA/FOTO models can provide average traffic flow characteristics within synchronized flow and wide moving jams. In turn, this permits the estimation of either travel time on a road section or travel time along any vehicle trajectory (see examples of trajectories 1-4 in Fig. 5).

ASDA/FOTO models for data measured by probe vehicles

Firstly, the ASDA and FOTO models identify transition points for phase transitions along the trajectory of a probe vehicle[10][11]. Each of the transition points is associated to the front separating spatially two of the three different traffic phases each other (free flow (F), synchronized flow (S), wide moving jam (J)). After the transition points have been found, the ASDA/FOTO models reconstruct regions of synchronized flow and wide moving jams in space and time with the use of empirical features of these traffic phases discussed above (see Figs. 2 and 4).

Publications

- B.S. Kerner, Introduction to Modern Traffic Flow Theory and Control: The Long Road to Three-Phase Traffic Theory, Springer, Berlin, New York 2009

- B.S. Kerner, The Physics of Traffic, Springer, Berlin, New York 2004

References

- Kerner B. S., Konhäuser P. (1994). Structure and parameters of clusters in traffic flow, Physical Review E, Vol. 50, 54

- Kerner B. S., Rehborn H. (1996). Experimental features and characteristics of traffic jams. Physical Review E, Vol. 53, 1297

- Kerner B. S., Rehborn H. (1996). Experimental properties of complexity in traffic flow. Physical Review E, Vol. 53, R4257

- Kerner B. S., Kirschfink H., Rehborn H. (1997) Automatische Stauverfolgung auf Autobahnen, Straßenverkehrstechnik, No. 9, pp 430–438

- Kerner B. S., Rehborn H. (1998) Messungen des Verkehrsflusses: Charakteristische Eigenschaften von Staus auf Autobahnen, Internationales Verkehrswesen, 5/1998, pp 196–203

- Kerner B. S., Rehborn H., Aleksić M., Haug A., Lange R. (2000) Verfolgung und Vorhersage von Verkehrsstörungen auf Autobahnen mit ”ASDA” und ”FOTO” im online-Betrieb in der Verkehrsrechnerzentrale Rüsselsheim, Straßenverkehrstechnik, No. 10, pp 521–527

- Kerner B. S., Rehborn H., Aleksić M., Haug A. (2001) Methods for Tracing and Forecasting of Congested Traffic Patterns on Highways, Traffic Engineering and Control, 09/2001, pp 282–287

- Kerner B. S., Rehborn H., Aleksić M., Haug A., Lange R. (2001) Online Automatic tracing and forecasting of traffic patterns with models “ASDA” and “FOTO”, Traffic Engineering and Control, 11/2001, pp 345–350

- Kerner B. S., Rehborn H., Aleksić M., Haug A. (2004): Recognition and Tracing of Spatial-Temporal Congested Traffic Patterns on Freeways, Transportation Research C, 12, pp 369–400

- Palmer J., Rehborn H. (2007) ASDA/FOTO based on Kerner’s Three-Phase Traffic Theory in North-Rhine Westfalia (in German), Straßenverkehrstechnik, No. 8, pp 463–470

- Palmer J., Rehborn H., Mbekeani L. (2008) Traffic Congestion Interpretation Based on Kerner’s Three-Phase Traffic Theory in USA, In: Proceedings 15th World Congress on ITS, New York

- Palmer J., Rehborn H. (2009) Reconstruction of congested traffic patterns using traffic state detection in autonomous vehicles based on Kerner’s three-phase traffic theory, In: Proceedings of. 16th World Congress on ITS, Stockholm

- Rehborn H, Klenov S.L. (2009) Traffic Prediction of Congested Patterns, In: R. Meyers (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Complexity and Systems Science, Springer New York, 2009, pp 9500–9536

- Boris S. Kerner, Rehborn H, Klenov S L, Palmer J, Prinn M (2009) Verfahren zur Verkehrszustandsbestimmung in einem Fahrzeug, (Method for traffic state detection in a vehicle), German Patent publication DE 10 2008 003 039 A1.

Notes

- ^ Boris S. Kerner, Kirschfink H, Rehborn H; Method for the automatic monitoring of traffic including the analysis of back-up dynamics, Deutsches Patent DE19647127C2, USA patent: US 5861820 (Filed: 1996)

- ^ Boris S. Kerner, Rehborn H., Traffic surveillance method and vehicle flow control in a road network, Deutsche Patentoffenlegung DE19835979A1, USA patent: US 6587779B1 (Filed: 1998)

- ^ Boris S. Kerner, M. Aleksić, U. Denneler; Verfahren und Vorrichtung zur Verkehrszustandsüberwachung, Deutsches Patent DE19944077C1 (Filed: 1999)

- ^ Boris S. Kerner; Method for monitoring the condition of traffic for a traffic network comprising effective narrow points, Deutsche Patentoffenlegung DE19944075A1; USA patent: US 6813555B1; Japan: JP 2002117481 (Filed: 1999)

- ^ Boris S. Kerner Deutsches Patent DE10036789A1; Method for determining the traffic state in a traffic network with effective bottlenecks, USA patent: US 6522970B2 (Filed: 2000)

- ^ a b Boris S. Kerner, "Experimental Features of Self-Organization in Traffic Flow", Physical Review Letters, 81, 3797-3400 (1998)

- ^ a b Boris S. Kerner, "The physics of traffic", Physics World Magazine 12, 25-30 (August 1999)

- ^ a b Boris S. Kerner, "Congested Traffic Flow: Observations and Theory", Transportation Research Record, Vol. 1678, pp. 160-167 (1999)

- ^ George G. Stokes, "On a difficulty in the theory of sound", Philosopical Magazine, 33, pp 349-356 (1848)

- ^ B.S. Kerner, H. Rehborn, J. Palmer, S.L. Klenov, Using probe vehicle to generate jam warning messages, Traffic Engineering and Control Vol 52, No 3 141-148 (2011)

- ^ J. Palmer, H. Rehborn, B.S. Kerner, ASDA and FOTO Models based on Probe Vehicle Data, Traffic Engineering and Control Vol 52 No 4, 183-191 (2011)