Thermal resistance

Thermal resistance is a heat property and a measure of a temperature difference by which an object or material resist a heat flow (heat per time unit or thermal resistance). Thermal resistance is the reciprocal thermal conductance.

- Specific thermal resistance or specific thermal resistivity Rλ in (K·m)/W is a material constant.

- Absolute thermal resistance Rth in K/W is a specific property of a component. It is e.g., a characteristic of a heat sink.

Contents |

Absolute thermal resistance

Absolute thermal resistance is the temperature difference across a structure when a unit of heat energy flows through it in unit time. It is the reciprocal of thermal conductance. The SI units of thermal resistance are kelvins per watt or the equivalent degrees Celsius per watt (the two are the same since as intervals 1 K = 1 °C).

The thermal resistance of materials is of great interest to electronic engineers because most electrical components generate heat and need to be cooled. Electronic components malfunction or fail if they overheat, and some parts routinely need measures taken in the design stage to prevent this.

Explanation from a electronics point of view

Equivalent thermal circuits

The heat flow can be modelled by analogy to an electrical circuit where heat flow is represented by current, temperatures are represented by voltages, heat sources are represented by constant current sources, absolute thermal resistances are represented by resistors and thermal capacitances by capacitors.

The diagram shows an equivalent thermal circuit for a semiconductor device with a heat sink.

Example calculation

Consider a component such as a silicon transistor that is bolted to the metal frame of a piece of equipment. The transistor's manufacturer will specify parameters in the datasheet called the absolute thermal resistance from junction to case (symbol:  ), and the maximum allowable temperature of the semiconductor junction (symbol:

), and the maximum allowable temperature of the semiconductor junction (symbol:  ). The specification for the design should include a maximum temperature at which the circuit should function correctly. Finally, the designer should consider how the heat from the transistor will escape to the environment: this might be by convection into the air, with or without the aid of a heat sink, or by conduction through the printed circuit board. For simplicity, let us assume that the designer decides to bolt the transistor to a metal surface (or heat sink) that is guaranteed to be less than

). The specification for the design should include a maximum temperature at which the circuit should function correctly. Finally, the designer should consider how the heat from the transistor will escape to the environment: this might be by convection into the air, with or without the aid of a heat sink, or by conduction through the printed circuit board. For simplicity, let us assume that the designer decides to bolt the transistor to a metal surface (or heat sink) that is guaranteed to be less than  above the ambient temperature. Note: THS appears to be undefined.

above the ambient temperature. Note: THS appears to be undefined.

Given all this information, the designer can construct a model of the heat flow from the semiconductor junction, where the heat is generated, to the outside world. In our example, the heat has to flow from the junction to the case of the transistor, then from the case to the metalwork. We do not need to consider where the heat goes after that, because we are told that the metalwork will conduct heat fast enough to keep the temperature less than  above ambient: this is all we need to know.

above ambient: this is all we need to know.

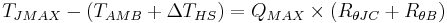

Suppose the engineer wishes to know how much power he can put into the transistor before it overheats. The calculations are as follows.

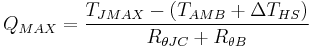

- Total absolute thermal resistance from junction to ambient =

where  is the absolute thermal resistance of the bond between the transistor's case and the metalwork. This figure depends on the nature of the bond - for example, a thermal bonding pad or thermal transfer grease might be used to reduce the absolute thermal resistance.

is the absolute thermal resistance of the bond between the transistor's case and the metalwork. This figure depends on the nature of the bond - for example, a thermal bonding pad or thermal transfer grease might be used to reduce the absolute thermal resistance.

- Maximum temperature drop from junction to ambient =

.

.

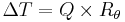

We use the general principle that the temperature drop  across a given absolute thermal resistance

across a given absolute thermal resistance  with a given heat flow

with a given heat flow  through it is:

through it is:

.

.

Substituting our own symbols into this formula gives:

,

,

and, rearranging,

The designer now knows  , the maximum power that the transistor can be allowed to dissipate, so he can design the circuit to limit the temperature of the transistor to a safe level.

, the maximum power that the transistor can be allowed to dissipate, so he can design the circuit to limit the temperature of the transistor to a safe level.

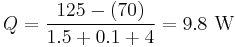

Let us plug in some sample numbers:

(typical for a silicon transistor)

(typical for a silicon transistor) (a typical specification for commercial equipment)

(a typical specification for commercial equipment) (for a typical TO-220 package)

(for a typical TO-220 package) (a typical value for an elastomer heat-transfer pad for a TO-220 package)

(a typical value for an elastomer heat-transfer pad for a TO-220 package) (a typical value for a heatsink for a TO-220 package)

(a typical value for a heatsink for a TO-220 package)

The result is then:

This means that the transistor can dissipate about 9 watts before it overheats. A cautious designer would operate the transistor at a lower power level to increase its reliability.

This method can be generalised to include any number of layers of heat-conducting materials, simply by adding together the absolute thermal resistances of the layers and the temperature drops across the layers.

Derived from Fourier's Law for heat conduction

From Fourier's Law for heat conduction, the following equation can be derived, and is valid as long as all of the parameters (x, A, and k) are constant throughout the sample.

where:

is the absolute thermal resistance (across the length of the material) (K/W)

is the absolute thermal resistance (across the length of the material) (K/W)- x is the length of the material (measured on a path parallel to the heat flow) (m)

- k is the thermal conductivity of the material ( W/(K·m) )

- A is the total cross sectional area of the material (measured perpendicular to the heat flow) (m2)

References

- Michael Lenz, Günther Striedl, Ulrich Fröhler (January 2000) Thermal Resistance, Theory and Practice. Infineon Technologies AG, Munich, Germany.

- Directed Energy, Inc./IXYSRF (March 31, 2003) R Theta And Power Dissipation Technical Note. Ixys RF, Fort Collins, Colorado. Example thermal resistance and power dissipation calculation in semiconductors.