TetraVex

TetraVex is a puzzle computer game, available for Windows and Linux systems.

Contents |

Gameplay

TetraVex is an edge-matching puzzle. The player is presented with a grid (by default, 3x3) and nine square tiles, each with a number on each edge. The objective of the game is to place the tiles in the grid in the proper position as fast as possible. Two tiles can only be placed next to each other if the numbers on adjacent faces match.

Availability

TetraVex was originally available for Windows in Windows Entertainment Pack 3. It was later re-released as part of the Best of Windows Entertainment Pack. It is also available as an open source game on the GNOME desktop.

Origins

The original version of TetraVex (for the Windows Entertainment Pack 3) was written (and named) by Scott Ferguson who was also the Development Lead and an architect of the first version of Visual Basic.[1] TetraVex was inspired by "the problem of tiling the plane" as described by Donald Knuth on page 382 of Volume 1: Fundamental Algorithms, the first book in his The Art of Computer Programming series.

In the TetraVex version for Windows, the Microsoft Blibbet logo is displayed if the player solves a 6 by 6 puzzle.

The tiles are also known as McMahon Squares, named for Percy McMahon who explored their possibilities in the 1920s.[2]

Counting the possible number of TetraVex

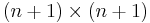

Since the game is simple in its definition, it is easy to count how many possible TetraVex are for each grid of size  . For instance, if

. For instance, if  , there are

, there are  possible squares with a number from zero to nine on each edge. Therefore for

possible squares with a number from zero to nine on each edge. Therefore for  there are

there are  possible TetraVex puzzles.

possible TetraVex puzzles.

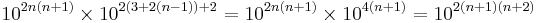

Proposition: There are  possible TetraVex in a grid of size

possible TetraVex in a grid of size  .

.

Proof sketch: For  this is true. We can proceed with mathematical induction.

this is true. We can proceed with mathematical induction.

Take a grid of  . The first

. The first  rows and the first

rows and the first  columns form a grid of

columns form a grid of  and by the hypothesis of induction, there are

and by the hypothesis of induction, there are  possible TetraVex on that subgrid. Now, for each possible TetraVex on the subgrid, we can choose

possible TetraVex on that subgrid. Now, for each possible TetraVex on the subgrid, we can choose  squares to be placed in the position

squares to be placed in the position  of the grid (first row, last column), because only one side is determined. Once this square is chosen, there are

of the grid (first row, last column), because only one side is determined. Once this square is chosen, there are  squares available to be placed in the position

squares available to be placed in the position  , and fixing that square we have

, and fixing that square we have  possibilities for the square on position

possibilities for the square on position  . We can go on until the square on position

. We can go on until the square on position  is fixed.

is fixed.

The same is true for the last row: there are  possibilities for the square on the first column and last row, and

possibilities for the square on the first column and last row, and  for all the other.

for all the other.

This gives us  . Then the proposition is proven by induction.

. Then the proposition is proven by induction.

It is easy to see that if the edges of the squares are allowed to take  possible numbers, then there are

possible numbers, then there are  possible TetraVex puzzles.

possible TetraVex puzzles.

See also

References

- ^ "The Birth of Visual Basic". Forestmoon.com. http://www.forestmoon.com/BIRTHofVB/BIRTHofVB.html. Retrieved 2010-05-11.

- ^ "MacMahon squares". Daviddarling.info. 2007-02-01. http://www.daviddarling.info/encyclopedia/M/MacMahon_squares.html. Retrieved 2010-07-30.