Tax rate

In a tax system and in economics, the tax rate describes the burden ratio (usually expressed as a percentage) at which a business or person is taxed. There are several methods used to present a tax rate: statutory, average, marginal, effective, effective average, and effective marginal. These rates can also be presented using different definitions applied to a tax base: inclusive and exclusive.

Contents |

Statutory

A statutory tax rate is the legally imposed rate. An income tax could have multiple statutory rates for different income levels, where a sales tax may have a flat statutory rate.[1]

Average

An average tax rate is the ratio of the amount of taxes paid to the tax base (taxable income or spending).[1]

- To calculate the average tax rate on an income tax, divide total tax liability by taxable income:

- Let

be the average tax rate.

be the average tax rate. - Let

be the tax liability.

be the tax liability. - Let

be the taxable income.

be the taxable income.

Marginal

A marginal tax rate is the tax rate that applies to the last dollar of the tax base (taxable income or spending),[1] and is often applied to the change in one's tax obligation as income rises:

- To calculate the marginal tax rate on an income tax:

- Let

be the marginal tax rate.

be the marginal tax rate. - Let

be the tax liability.

be the tax liability. - Let

be the taxable income.

be the taxable income.

For an individual, it can be determined by increasing or decreasing the income earned or spent and calculating the change in taxes payable. An individual's tax bracket is the range of income for which a given marginal tax rate applies. The marginal tax rate may increase or decrease as income or consumption increases, although in most countries the tax rate is (in principle) progressive. In such cases, the average tax rate will be lower than the marginal tax rate: an individual may have a marginal tax rate of 45%, but pay average tax of half this amount.

In a jurisdiction with a flat tax on earnings, every taxpayer pays the same percentage of income, regardless of income or consumption. Some proponents of this system propose to exempt a fixed amount of earnings (such as the first $10,000) from the flat tax. In a revenue neutral situation in jurisdictions with progressive taxation regimes, where imposition of a "flat tax" would target neither an increase nor decrease in the total tax revenue, the net effect of the flat tax would be to shift a significant portion of the tax burden from wealthier tax brackets to less wealthy tax brackets.

In economics, marginal tax rates are important because they are one of the factors that determine incentives to increase income; at higher marginal tax rates, some argue, the individual has less incentive to earn more. This is the foundation of the Laffer curve, which claims taxable income decreases as a function of marginal tax rate, and therefore tax revenue begins to decrease after a certain point.

Public discussion of "high taxes" may refer to overall tax rates or marginal taxes.

Marginal tax rates may be published explicitly, together with the corresponding tax brackets, but they can also be derived from published tax tables showing the tax for each income. It may be calculated noting how tax changes with changes in pre-tax income, rather than with taxable income.

Marginal tax rates do not fully describe the impact of taxation. A flat rate poll tax has a marginal rate of zero, but a discontinuity in tax paid can lead to positively or negatively infinite marginal rates at particular points.

Effective

An effective tax rate refers to the actual rate, the rate existing in fact.[1] Both average and marginal tax rates can be expressed as effective tax rates.

The effective tax rate is the amount of tax an individual or firm pays when all other government tax offsets or payments are applied, divided by the tax base (total income or spending).[2] If certain groups have high degrees of tax offsets compared to other groups, their effective tax rate will be different, even where their official tax rates and marginal tax rates will be equal. The effective rate of tax can often be discussed in terms of the effective marginal rate of tax, namely, the amount of effective tax paid as a percentage of the last dollar earned or spent.

Effective average

An effective average tax rate (or average effective tax rate) may differ from an average tax rate because some measure of income other than taxable income is used. For example, the Joint Committee on Taxation typically calculates the effective average tax rate as the ratio of taxes paid to a constructed measure of "economic income".[1]

Effective marginal

An effective marginal tax rate (or marginal effective tax rate, marginal deduction rate) may differ from a marginal tax rate because the taxpayer may be in an income range in which the person is subject to a phase-out of some exclusion or deduction.[1] Where social security and other benefits are related to income, the combined tax and benefit effect can also be taken into account giving a result sometimes described as the marginal effective tax rate or the marginal deduction rate. If the marginal deduction rate exceeds 100%, an increase in gross income leads to a decrease in disposable income, discouraging attempts to increase income. When this occurs for low-income individuals, it is known as the welfare trap.

Inclusive/exclusive

Tax rates can be presented differently due to differing definitions of tax base, which can make comparisons between tax systems confusing.

Some tax systems include the taxes owed in the tax base (tax-inclusive), while other tax systems do not include taxes owed as part of the base (tax-exclusive).[3] In the United States, sales taxes are usually quoted exclusively and income taxes are quoted inclusively. The majority of Europe, value added tax (VAT) countries, include the tax amount when quoting merchandise prices, including Goods and Services Tax (GST) countries, such as Australia and New Zealand. However, those countries still define their tax rates on a tax exclusive basis.

For direct rate comparisons between exclusive and inclusive taxes, one rate must be manipulated to look like the other. When a tax system imposes taxes primarily on income, the tax base is a household's pre-tax income. The appropriate income tax rate is applied to the tax base to calculate taxes owed. Under this formula, taxes to be paid are included in the base on which the tax rate is imposed. If an individual's gross income is $100 and income tax rate is 20%, taxes owed equals $20.

The income tax is taken "off the top", so the individual is left with $80 in after-tax money. Some tax laws impose taxes on a tax base equal to the pre-tax portion of a good's price. Unlike the income tax example above, these taxes do not include actual taxes owed as part of the base. A good priced at $80 with a 25% exclusive sales tax rate yields $20 in taxes owed. Since the sales tax is added "on the top", the individual pays $20 of tax on $80 of pre-tax goods for a total cost of $100. In either case, the tax base of $100 can be treated as two parts—$80 of after-tax spending money and $20 of taxes owed. A 25% exclusive tax rate approximates a 20% inclusive tax rate after adjustment.[3] By including taxes owed in the tax base, an exclusive tax rate can be directly compared to an inclusive tax rate.

- Inclusive income tax rate comparison to an exclusive sales tax rate:

- Let

be the income tax rate. For a 20% rate, then

be the income tax rate. For a 20% rate, then

- Let

be the rate in terms of a sales tax.

be the rate in terms of a sales tax. - Let

be the price of the good (including the tax).

be the price of the good (including the tax).

- The revenue that would go to the government:

- The revenue remaining for the seller of the good:

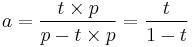

- To convert the tax, divide the money going to the government by the money the company nets:

- Therefore, to adjust any inclusive tax rate to that of an exclusive tax rate, divide the given rate by 1 minus that rate.

- 15% inclusive = 18% exclusive

- 20% inclusive = 25% exclusive

- 25% inclusive = 33% exclusive

- 33% inclusive = 50% exclusive

- 50% inclusive = 100% exclusive

See also

- Progressive tax

- Proportional tax

- Regressive tax

- Tax incidence

- Tax rates around the world

- List of countries by tax revenue as percentage of GDP

- Tax rates of Europe

- Tax exporting

- Capital flight

References

- ^ a b c d e f "What is the difference between statutory, average, marginal, and effective tax rates?". Americans For Fair Taxation. http://www.fairtax.org/PDF/WhatIsTheDifferenceBetweenTaxRates.pdf. Retrieved 2007-04-23.

- ^ "A statistical overview". Australian Commonwealth Government Treasury. http://comparativetaxation.treasury.gov.au/content/report/html/05_Chapter_3.asp. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- ^ a b Bachman, Paul; Haughton, Jonathan; Kotlikoff, Laurence J.; Sanchez-Penalver, Alfonso; Tuerck, David G. (2006-11). "Taxing Sales under the FairTax – What Rate Works?". Beacon Hill Institute. Tax Analysts. http://www.beaconhill.org/FairTax2006/TaxingSalesundertheFairTaxWhatRateWorks061005.pdf. Retrieved 2007-04-24.