Surface tension

| Continuum mechanics |

|---|

|

Fluids

Fluid statics · Fluid dynamics Surface tension Navier–Stokes equations Viscosity: Newtonian, Non-Newtonian |

Surface tension is a property of the surface of a liquid that allows it to resist an external force. It is revealed, for example, in floating of some objects on the surface of water, even though they are denser than water, and in the ability of some insects (e.g. water striders) to run on the water surface. This property is caused by cohesion of similar molecules, and is responsible for many of the behaviors of liquids.

Surface tension has the dimension of force per unit length, or of energy per unit area. The two are equivalent—but when referring to energy per unit of area, people use the term surface energy—which is a more general term in the sense that it applies also to solids and not just liquids.

In materials science, surface tension is used for either surface stress or surface free energy.

Contents |

Causes

The cohesive forces among the liquid molecules are responsible for this phenomenon of surface tension. In the bulk of the liquid, each molecule is pulled equally in every direction by neighboring liquid molecules, resulting in a net force of zero. The molecules at the surface do not have other molecules on all sides of them and therefore are pulled inwards. This creates some internal pressure and forces liquid surfaces to contract to the minimal area.

Surface tension is responsible for the shape of liquid droplets. Although easily deformed, droplets of water tend to be pulled into a spherical shape by the cohesive forces of the surface layer. In the absence of other forces, including gravity, drops of virtually all liquids would be perfectly spherical. The spherical shape minimizes the necessary "wall tension" of the surface layer according to Laplace's law.

Another way to view it is in terms of energy. A molecule in contact with a neighbor is in a lower state of energy than if it were alone (not in contact with a neighbor). The interior molecules have as many neighbors as they can possibly have, but the boundary molecules are missing neighbors (compared to interior molecules) and therefore have a higher energy. For the liquid to minimize its energy state, the number of higher energy boundary molecules must be minimized. The minimized quantity of boundary molecules results in a minimized surface area.[1]

As a result of surface area minimization, a surface will assume the smoothest shape it can (mathematical proof that "smooth" shapes minimize surface area relies on use of the Euler–Lagrange equation). Since any curvature in the surface shape results in greater area, a higher energy will also result. Consequently the surface will push back against any curvature in much the same way as a ball pushed uphill will push back to minimize its gravitational potential energy.

Effects in everyday life

Water

Several effects of surface tension can be seen with ordinary water:

A. Beading of rain water on the surface of a waxy surface, such as a leaf. Water adheres weakly to wax and strongly to itself, so water clusters into drops. Surface tension gives them their near-spherical shape, because a sphere has the smallest possible surface area to volume ratio.

B. Formation of drops occurs when a mass of liquid is stretched. The animation shows water adhering to the faucet gaining mass until it is stretched to a point where the surface tension can no longer bind it to the faucet. It then separates and surface tension forms the drop into a sphere. If a stream of water were running from the faucet, the stream would break up into drops during its fall. Gravity stretches the stream, then surface tension pinches it into spheres.[2]

C. Floatation of objects denser than water occurs when the object is nonwettable and its weight is small enough to be borne by the forces arising from surface tension.[1] For example, water striders use surface tension to walk on the surface of a pond. The surface of the water behaves like an elastic film: the insect's feet cause indentations in the water's surface, increasing its surface area.[3]

D. Separation of oil and water (in this case, water and liquid wax) is caused by a tension in the surface between dissimilar liquids. This type of surface tension is called "interface tension", but its physics are the same.

E. Tears of wine is the formation of drops and rivulets on the side of a glass containing an alcoholic beverage. Its cause is a complex interaction between the differing surface tensions of water and ethanol; it is induced by a combination of surface tension modification of water by ethanol together with ethanol evaporating faster than water.

Surfactants

Surface tension is visible in other common phenomena, especially when surfactants are used to decrease it:

- Soap bubbles have very large surface areas with very little mass. Bubbles in pure water are unstable. The addition of surfactants, however, can have a stabilizing effect on the bubbles (see Marangoni effect). Notice that surfactants actually reduce the surface tension of water by a factor of three or more.

- Emulsions are a type of solution in which surface tension plays a role. Tiny fragments of oil suspended in pure water will spontaneously assemble themselves into much larger masses. But the presence of a surfactant provides a decrease in surface tension, which permits stability of minute droplets of oil in the bulk of water (or vice versa).

Basic physics

Two definitions

Surface tension, represented by the symbol γ is defined as the force along a line of unit length, where the force is parallel to the surface but perpendicular to the line. One way to picture this is to imagine a flat soap film bounded on one side by a taut thread of length, L. The thread will be pulled toward the interior of the film by a force equal to 2 L (the factor of 2 is because the soap film has two sides, hence two surfaces).[4] Surface tension is therefore measured in forces per unit length. Its SI unit is newton per meter but the cgs unit of dyne per cm is also used.[5] One dyn/cm corresponds to 0.001 N/m.

L (the factor of 2 is because the soap film has two sides, hence two surfaces).[4] Surface tension is therefore measured in forces per unit length. Its SI unit is newton per meter but the cgs unit of dyne per cm is also used.[5] One dyn/cm corresponds to 0.001 N/m.

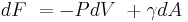

An equivalent definition, one that is useful in thermodynamics, is work done per unit area. As such, in order to increase the surface area of a mass of liquid by an amount, δA, a quantity of work,  δA, is needed.[4] This work is stored as potential energy. Consequently surface tension can be also measured in SI system as joules per square meter and in the cgs system as ergs per cm2. Since mechanical systems try to find a state of minimum potential energy, a free droplet of liquid naturally assumes a spherical shape, which has the minimum surface area for a given volume.

δA, is needed.[4] This work is stored as potential energy. Consequently surface tension can be also measured in SI system as joules per square meter and in the cgs system as ergs per cm2. Since mechanical systems try to find a state of minimum potential energy, a free droplet of liquid naturally assumes a spherical shape, which has the minimum surface area for a given volume.

The equivalence of measurement of energy per unit area to force per unit length can be proven by dimensional analysis.[4]

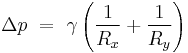

Surface curvature and pressure

If no force acts normal to a tensioned surface, the surface must remain flat. But if the pressure on one side of the surface differs from pressure on the other side, the pressure difference times surface area results in a normal force. In order for the surface tension forces to cancel the force due to pressure, the surface must be curved. The diagram shows how surface curvature of a tiny patch of surface leads to a net component of surface tension forces acting normal to the center of the patch. When all the forces are balanced, the resulting equation is known as the Young–Laplace equation:[6]

where:

-

- Δp is the pressure difference.

is surface tension.

is surface tension.- Rx and Ry are radii of curvature in each of the axes that are parallel to the surface.

The quantity in parentheses on the right hand side is in fact (twice) the mean curvature of the surface (depending on normalisation).

Solutions to this equation determine the shape of water drops, puddles, menisci, soap bubbles, and all other shapes determined by surface tension (such as the shape of the impressions that a water strider's feet make on the surface of a pond).

The table below shows how the internal pressure of a water droplet increases with decreasing radius. For not very small drops the effect is subtle, but the pressure difference becomes enormous when the drop sizes approach the molecular size. (In the limit of a single molecule the concept becomes meaningless.)

| Δp for water drops of different radii at STP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Droplet radius | 1 mm | 0.1 mm | 1 μm | 10 nm |

| Δp (atm) | 0.0014 | 0.0144 | 1.436 | 143.6 |

Liquid surface

To find the shape of the minimal surface bounded by some arbitrary shaped frame using strictly mathematical means can be a daunting task. Yet by fashioning the frame out of wire and dipping it in soap-solution, a locally minimal surface will appear in the resulting soap-film within seconds.[4][7]

The reason for this is that the pressure difference across a fluid interface is proportional to the mean curvature, as seen in the Young-Laplace equation. For an open soap film, the pressure difference is zero, hence the mean curvature is zero, and minimal surfaces have the property of zero mean curvature.

Contact angles

The surface of any liquid is an interface between that liquid and some other medium.[note 1] The top surface of a pond, for example, is an interface between the pond water and the air. Surface tension, then, is not a property of the liquid alone, but a property of the liquid's interface with another medium. If a liquid is in a container, then besides the liquid/air interface at its top surface, there is also an interface between the liquid and the walls of the container. The surface tension between the liquid and air is usually different (greater than) its surface tension with the walls of a container. And where the two surfaces meet, their geometry must be such that all forces balance.[4][6]

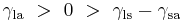

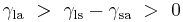

Where the two surfaces meet, they form a contact angle,  , which is the angle the tangent to the surface makes with the solid surface. The diagram to the right shows two examples. Tension forces are shown for the liquid-air interface, the liquid-solid interface, and the solid-air interface. The example on the left is where the difference between the liquid-solid and solid-air surface tension,

, which is the angle the tangent to the surface makes with the solid surface. The diagram to the right shows two examples. Tension forces are shown for the liquid-air interface, the liquid-solid interface, and the solid-air interface. The example on the left is where the difference between the liquid-solid and solid-air surface tension,  , is less than the liquid-air surface tension,

, is less than the liquid-air surface tension,  , but is nevertheless positive, that is

, but is nevertheless positive, that is

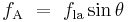

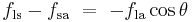

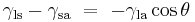

In the diagram, both the vertical and horizontal forces must cancel exactly at the contact point, known as equilibrium. The horizontal component of  is canceled by the adhesive force,

is canceled by the adhesive force,  .[4]

.[4]

The more telling balance of forces, though, is in the vertical direction. The vertical component of  must exactly cancel the force,

must exactly cancel the force,  .[4]

.[4]

| Liquid | Solid | Contact angle | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| water |

|

0° | |||

| ethanol | |||||

| diethyl ether | |||||

| carbon tetrachloride | |||||

| glycerol | |||||

| acetic acid | |||||

| water | paraffin wax | 107° | |||

| silver | 90° | ||||

| methyl iodide | soda-lime glass | 29° | |||

| lead glass | 30° | ||||

| fused quartz | 33° | ||||

| mercury | soda-lime glass | 140° | |||

| Some liquid-solid contact angles[4] | |||||

Since the forces are in direct proportion to their respective surface tensions, we also have:[6]

where

This means that although the difference between the liquid-solid and solid-air surface tension,  , is difficult to measure directly, it can be inferred from the liquid-air surface tension,

, is difficult to measure directly, it can be inferred from the liquid-air surface tension,  , and the equilibrium contact angle,

, and the equilibrium contact angle,  , which is a function of the easily measurable advancing and receding contact angles (see main article contact angle).

, which is a function of the easily measurable advancing and receding contact angles (see main article contact angle).

This same relationship exists in the diagram on the right. But in this case we see that because the contact angle is less than 90°, the liquid-solid/solid-air surface tension difference must be negative:

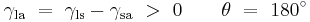

Special contact angles

Observe that in the special case of a water-silver interface where the contact angle is equal to 90°, the liquid-solid/solid-air surface tension difference is exactly zero.

Another special case is where the contact angle is exactly 180°. Water with specially prepared Teflon approaches this.[6] Contact angle of 180° occurs when the liquid-solid surface tension is exactly equal to the liquid-air surface tension.

Methods of measurement

Because surface tension manifests itself in various effects, it offers a number of paths to its measurement. Which method is optimal depends upon the nature of the liquid being measured, the conditions under which its tension is to be measured, and the stability of its surface when it is deformed.

- Du Noüy Ring method: The traditional method used to measure surface or interfacial tension. Wetting properties of the surface or interface have little influence on this measuring technique. Maximum pull exerted on the ring by the surface is measured.[8]

- Du Noüy-Padday method: A minimized version of Du Noüy method uses a small diameter metal needle instead of a ring, in combination with a high sensitivity microbalance to record maximum pull. The advantage of this method is that very small sample volumes (down to few tens of microliters) can be measured with very high precision, without the need to correct for buoyancy (for a needle or rather, rod, with proper geometry). Further, the measurement can be performed very quickly, minimally in about 20 seconds. First commercial multichannel tensiometers [CMCeeker] were recently built based on this principle.

- Wilhelmy plate method: A universal method especially suited to check surface tension over long time intervals. A vertical plate of known perimeter is attached to a balance, and the force due to wetting is measured.[9]

- Spinning drop method: This technique is ideal for measuring low interfacial tensions. The diameter of a drop within a heavy phase is measured while both are rotated.

- Pendant drop method: Surface and interfacial tension can be measured by this technique, even at elevated temperatures and pressures. Geometry of a drop is analyzed optically. For details, see Drop.[9]

- Bubble pressure method (Jaeger's method): A measurement technique for determining surface tension at short surface ages. Maximum pressure of each bubble is measured.

- Drop volume method: A method for determining interfacial tension as a function of interface age. Liquid of one density is pumped into a second liquid of a different density and time between drops produced is measured.[10]

- Capillary rise method: The end of a capillary is immersed into the solution. The height at which the solution reaches inside the capillary is related to the surface tension by the equation discussed below.[11]

- Stalagmometric method: A method of weighting and reading a drop of liquid.

- Sessile drop method: A method for determining surface tension and density by placing a drop on a substrate and measuring the contact angle (see Sessile drop technique).[12]

- Vibrational frequency of levitated drops: The natural frequency of vibrational oscillations of magnetically levitated drops has been used to measure the surface tension of superfluid 4He. This value is estimated to be 0.375 dyn/cm at T = 0 K.[13]

Effects

Liquid in a vertical tube

An old style mercury barometer consists of a vertical glass tube about 1 cm in diameter partially filled with mercury, and with a vacuum (called Torricelli's vacuum) in the unfilled volume (see diagram to the right). Notice that the mercury level at the center of the tube is higher than at the edges, making the upper surface of the mercury dome-shaped. The center of mass of the entire column of mercury would be slightly lower if the top surface of the mercury were flat over the entire crossection of the tube. But the dome-shaped top gives slightly less surface area to the entire mass of mercury. Again the two effects combine to minimize the total potential energy. Such a surface shape is known as a convex meniscus.

The reason we consider the surface area of the entire mass of mercury, including the part of the surface that is in contact with the glass, is because mercury does not adhere at all to glass. So the surface tension of the mercury acts over its entire surface area, including where it is in contact with the glass. If instead of glass, the tube were made out of copper, the situation would be very different. Mercury aggressively adheres to copper. So in a copper tube, the level of mercury at the center of the tube will be lower than at the edges (that is, it would be a concave meniscus). In a situation where the liquid adheres to the walls of its container, we consider the part of the fluid's surface area that is in contact with the container to have negative surface tension. The fluid then works to maximize the contact surface area. So in this case increasing the area in contact with the container decreases rather than increases the potential energy. That decrease is enough to compensate for the increased potential energy associated with lifting the fluid near the walls of the container.

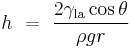

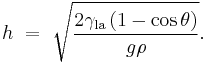

If a tube is sufficiently narrow and the liquid adhesion to its walls is sufficiently strong, surface tension can draw liquid up the tube in a phenomenon known as capillary action. The height the column is lifted to is given by:[4]

where

-

is the height the liquid is lifted,

is the height the liquid is lifted, is the liquid-air surface tension,

is the liquid-air surface tension, is the density of the liquid,

is the density of the liquid, is the radius of the capillary,

is the radius of the capillary, is the acceleration due to gravity,

is the acceleration due to gravity, is the angle of contact described above. If

is the angle of contact described above. If  is greater than 90°, as with mercury in a glass container, the liquid will be depressed rather than lifted.

is greater than 90°, as with mercury in a glass container, the liquid will be depressed rather than lifted.

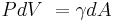

Puddles on a surface

Pouring mercury onto a horizontal flat sheet of glass results in a puddle that has a perceptible thickness. The puddle will spread out only to the point where it is a little under half a centimeter thick, and no thinner. Again this is due to the action of mercury's strong surface tension. The liquid mass flattens out because that brings as much of the mercury to as low a level as possible, but the surface tension, at the same time, is acting to reduce the total surface area. The result is the compromise of a puddle of a nearly fixed thickness.

The same surface tension demonstration can be done with water, lime water or even saline, but only on a surface made of a substance that the water does not adhere to. Wax is such a substance. Water poured onto a smooth, flat, horizontal wax surface, say a waxed sheet of glass, will behave similarly to the mercury poured onto glass.

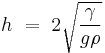

The thickness of a puddle of liquid on a surface whose contact angle is 180° is given by:[6]

where

-

is the depth of the puddle in centimeters or meters.

is the depth of the puddle in centimeters or meters. is the surface tension of the liquid in dynes per centimeter or newtons per meter.

is the surface tension of the liquid in dynes per centimeter or newtons per meter. is the acceleration due to gravity and is equal to 980 cm/s2 or 9.8 m/s2

is the acceleration due to gravity and is equal to 980 cm/s2 or 9.8 m/s2 is the density of the liquid in grams per cubic centimeter or kilograms per cubic meter

is the density of the liquid in grams per cubic centimeter or kilograms per cubic meter

In reality, the thicknesses of the puddles will be slightly less than what is predicted by the above formula because very few surfaces have a contact angle of 180° with any liquid. When the contact angle is less than 180°, the thickness is given by:[6]

For mercury on glass, γHg = 487 dyn/cm, ρHg = 13.5 g/cm3 and θ = 140°, which gives hHg = 0.36 cm. For water on paraffin at 25 °C, γ = 72 dyn/cm, ρ = 1.0 g/cm3, and θ = 107° which gives hH2O = 0.44 cm.

The formula also predicts that when the contact angle is 0°, the liquid will spread out into a micro-thin layer over the surface. Such a surface is said to be fully wettable by the liquid.

The breakup of streams into drops

In day-to-day life we all observe that a stream of water emerging from a faucet will break up into droplets, no matter how smoothly the stream is emitted from the faucet. This is due to a phenomenon called the Plateau–Rayleigh instability,[6] which is entirely a consequence of the effects of surface tension.

The explanation of this instability begins with the existence of tiny perturbations in the stream. These are always present, no matter how smooth the stream is. If the perturbations are resolved into sinusoidal components, we find that some components grow with time while others decay with time. Among those that grow with time, some grow at faster rates than others. Whether a component decays or grows, and how fast it grows is entirely a function of its wave number (a measure of how many peaks and troughs per centimeter) and the radii of the original cylindrical stream.

Thermodynamics

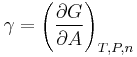

As stated above, the mechanical work needed to increase a surface is  . Hence at constant temperature and pressure, surface tension equals Gibbs free energy per surface area:[6]

. Hence at constant temperature and pressure, surface tension equals Gibbs free energy per surface area:[6]

where  is Gibbs free energy and

is Gibbs free energy and  is the area.

is the area.

Thermodynamics requires that all spontaneous changes of state are accompanied by a decrease in Gibbs free energy.

From this it is easy to understand why decreasing the surface area of a mass of liquid is always spontaneous ( ), provided it is not coupled to any other energy changes. It follows that in order to increase surface area, a certain amount of energy must be added.

), provided it is not coupled to any other energy changes. It follows that in order to increase surface area, a certain amount of energy must be added.

Gibbs free energy is defined by the equation,[14]  , where

, where  is enthalpy and

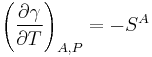

is enthalpy and  is entropy. Based upon this and the fact that surface tension is Gibbs free energy per unit area, it is possible to obtain the following expression for entropy per unit area:

is entropy. Based upon this and the fact that surface tension is Gibbs free energy per unit area, it is possible to obtain the following expression for entropy per unit area:

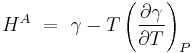

Kelvin's Equation for surfaces arises by rearranging the previous equations. It states that surface enthalpy or surface energy (different from surface free energy) depends both on surface tension and its derivative with temperature at constant pressure by the relationship.[15]

Thermodynamics of soap bubble

The pressure inside an ideal (one surface) soap bubble can be derived from thermodynamic free energy considerations. At constant temperature and particle number,  , the differential Helmholtz free energy is given by

, the differential Helmholtz free energy is given by

where  is the difference in pressure inside and outside of the bubble, and

is the difference in pressure inside and outside of the bubble, and  is the surface tension. In equilibrium,

is the surface tension. In equilibrium,  , and so,

, and so,

-

.

.

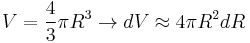

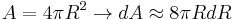

For a spherical bubble, the volume and surface area are given simply by

-

,

,

and

-

.

.

Substituting these relations into the previous expression, we find

-

,

,

which is equivalent to the Young-Laplace equation when Rx = Ry. For real soap bubbles, the pressure is doubled due to the presence of two interfaces, one inside and one outside.

Influence of temperature

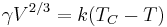

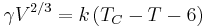

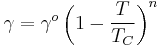

Surface tension is dependent on temperature. For that reason, when a value is given for the surface tension of an interface, temperature must be explicitly stated. The general trend is that surface tension decreases with the increase of temperature, reaching a value of 0 at the critical temperature. For further details see Eötvös rule. There are only empirical equations to relate surface tension and temperature:

Here V is the molar volume of a substance, TC is the critical temperature and k is a constant valid for almost all substances.[8] A typical value is k = 2.1 x 10−7 [J K−1 mol−2/3].[8][16] For water one can further use V = 18 ml/mol and TC = 374°C.

A variant on Eötvös is described by Ramay and Shields:[14]

where the temperature offset of 6 kelvins provides the formula with a better fit to reality at lower temperatures.

- Guggenheim-Katayama:[15]

is a constant for each liquid and n is an empirical factor, whose value is 11/9 for organic liquids. This equation was also proposed by van der Waals, who further proposed that

is a constant for each liquid and n is an empirical factor, whose value is 11/9 for organic liquids. This equation was also proposed by van der Waals, who further proposed that  could be given by the expression,

could be given by the expression,  , where

, where  is a universal constant for all liquids, and

is a universal constant for all liquids, and  is the critical pressure of the liquid (although later experiments found

is the critical pressure of the liquid (although later experiments found  to vary to some degree from one liquid to another).[15]

to vary to some degree from one liquid to another).[15]

Both Guggenheim-Katayama and Eötvös take into account the fact that surface tension reaches 0 at the critical temperature, whereas Ramay and Shields fails to match reality at this endpoint.

Influence of solute concentration

Solutes can have different effects on surface tension depending on their structure:

- Little or no effect, for example sugar

- Increase surface tension, inorganic salts

- Decrease surface tension progressively, alcohols

- Decrease surface tension and, once a minimum is reached, no more effect: surfactants

What complicates the effect is that a solute can exist in a different concentration at the surface of a solvent than in its bulk. This difference varies from one solute/solvent combination to another.

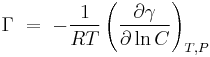

Gibbs isotherm states that:[14]

is known as surface concentration, it represents excess of solute per unit area of the surface over what would be present if the bulk concentration prevailed all the way to the surface. It has units of mol/m2

is known as surface concentration, it represents excess of solute per unit area of the surface over what would be present if the bulk concentration prevailed all the way to the surface. It has units of mol/m2

is the concentration of the substance in the bulk solution.

is the concentration of the substance in the bulk solution.

is the gas constant and

is the gas constant and  the temperature

the temperature

Certain assumptions are taken in its deduction, therefore Gibbs isotherm can only be applied to ideal (very dilute) solutions with two components.

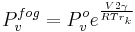

Influence of particle size on vapor pressure

The Clausius-Clapeyron relation leads to another equation also attributed to Kelvin. It explains why, because of surface tension, the vapor pressure for small droplets of liquid in suspension is greater than standard vapor pressure of that same liquid when the interface is flat. That is to say that when a liquid is forming small droplets, the equilibrium concentration of its vapor in its surroundings is greater. This arises because the pressure inside the droplet is greater than outside.[14]

-

is the standard vapor pressure for that liquid at that temperature and pressure.

is the standard vapor pressure for that liquid at that temperature and pressure. is the molar volume.

is the molar volume. is the gas constant

is the gas constant

is the Kelvin radius, the radius of the droplets.

is the Kelvin radius, the radius of the droplets.

The effect explains supersaturation of vapors. In the absence of nucleation sites, tiny droplets must form before they can evolve into larger droplets. This requires a vapor pressure many times the vapor pressure at the phase transition point.[14]

This equation is also used in catalyst chemistry to assess mesoporosity for solids.[17]

The effect can be viewed in terms of the average number of molecular neighbors of surface molecules (see diagram).

The table shows some calculated values of this effect for water at different drop sizes:

| P/P0 for water drops of different radii at STP[15] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Droplet radius (nm) | 1000 | 100 | 10 | 1 |

| P/P0 | 1.001 | 1.011 | 1.114 | 2.95 |

The effect becomes clear for very small drop sizes, as a drop of 1 nm radius has about 100 molecules inside, which is a quantity small enough to require a quantum mechanics analysis.

Data table

| Liquid | Temperature °C | Surface tension, γ |

|---|---|---|

| Acetic acid | 20 | 27.6 |

| Acetic acid (40.1%) + Water | 30 | 40.68 |

| Acetic acid (10.0%) + Water | 30 | 54.56 |

| Acetone | 20 | 23.7 |

| Diethyl ether | 20 | 17.0 |

| Ethanol | 20 | 22.27 |

| Ethanol (40%) + Water | 25 | 29.63 |

| Ethanol (11.1%) + Water | 25 | 46.03 |

| Glycerol | 20 | 63 |

| n-Hexane | 20 | 18.4 |

| Hydrochloric acid 17.7M aqueous solution | 20 | 65.95 |

| Isopropanol | 20 | 21.7 |

| Liquid Nitrogen | -196 | 8.85 |

| Mercury | 15 | 487 |

| Methanol | 20 | 22.6 |

| n-Octane | 20 | 21.8 |

| Sodium chloride 6.0M aqueous solution | 20 | 82.55 |

| Sucrose (55%) + water | 20 | 76.45 |

| Water | 0 | 75.64 |

| Water | 25 | 71.97 |

| Water | 50 | 67.91 |

| Water | 100 | 58.85 |

See also

- Anti-fog

- Capillary wave—short waves on a water surface, governed by surface tension and inertia

- Cheerio effect—the tendency for small wettable floating objects to attract one another.

- Cohesion

- Dimensionless numbers

- Dortmund Data Bank—contains experimental temperature-dependent surface tensions.

- Electrodipping force

- Electrowetting

- Eötvös rule—a rule for predicting surface tension dependent on temperature.

- Fluid pipe

- Hydrostatic equilibrium—the effect of gravity pulling matter into a round shape.

- Meniscus—surface curvature formed by a liquid in a container.

- Mercury beating heart—a consequence of inhomogeneous surface tension.

- Microfluidics

- Sessile drop technique

- Specific surface energy—same as surface tension in isotropic materials.

- Spinning drop method

- Stalagmometric method

- Surface tension values

- Surfactants—substances which reduce surface tension.

- Tears of wine—the surface tension induced phenomenon seen on the sides of glasses containing alcoholic beverages.

- Tolman length—leading term in correcting the surface tension for curved surfaces.

- Wetting and dewetting

Gallery of effects

Notes

- ^ In a mercury barometer, the upper liquid surface is an interface between the liquid and a vacuum containing some molecules of evaporated liquid.

References

- ^ a b c White, Harvey E. (1948). Modern College Physics. van Nostrand. ISBN 0442294018.

- ^ John W. M. Bush (May 2004). "MIT Lecture Notes on Surface Tension, lecture 5" (PDF). Massachusetts Institute of Technology. http://web.mit.edu/1.63/www/Lec-notes/Surfacetension/Lecture5.pdf. Retrieved April 1, 2007.

- ^ John W. M. Bush (May 2004). "MIT Lecture Notes on Surface Tension, lecture 3" (PDF). Massachusetts Institute of Technology. http://web.mit.edu/1.63/www/Lec-notes/Surfacetension/Lecture3.pdf. Retrieved April 1, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Sears, Francis Weston; Zemanski, Mark W. University Physics 2nd ed. Addison Wesley 1955

- ^ John W. M. Bush (April 2004). "MIT Lecture Notes on Surface Tension, lecture 1" (PDF). Massachusetts Institute of Technology. http://web.mit.edu/1.63/www/Lec-notes/Surfacetension/Lecture1.pdf. Retrieved April 1, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Pierre-Gilles de Gennes; Françoise Brochard-Wyart; David Quéré (2002). Capillary and Wetting Phenomena—Drops, Bubbles, Pearls, Waves. Alex Reisinger. Springer. ISBN 0-387-00592-7.

- ^ Aaronson, Scott. "NP-Complete Problems and physical reality.". SIGACT News. http://www.scottaaronson.com/papers/npcomplete.pdf.

- ^ a b c d "Surface Tension by the Ring Method (Du Nouy Method)" (PDF). PHYWE. http://www.nikhef.nl/~h73/kn1c/praktikum/phywe/LEP/Experim/1_4_05.pdf. Retrieved 2007-09-08.

- ^ a b "Surface and Interfacial Tension". Langmuir-Blodgett Instruments. http://www.ksvinc.com/surface_tension1.htm. Retrieved 2007-09-08.

- ^ "Surfacants at interfaces" (PDF). lauda.de. http://lauda.de/hosting/lauda/webres.nsf/urlnames/graphics_tvt2/$file/Tensio-dyn-meth-e.pdf. Retrieved 2007-09-08.

- ^ Calvert, James B. "Surface Tension (physics lecture notes)". University of Denver. http://mysite.du.edu/~jcalvert/phys/surftens.htm. Retrieved 2007-09-08.

- ^ "Sessile Drop Method". Dataphysics. Archived from the original on August 8, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20070808082309/http://www.dataphysics.de/english/messmeth_sessil.htm. Retrieved 2007-09-08.

- ^ Vicente, C.; Yao, W.; Maris, H.; Seidel, G. (2002). "Surface tension of liquid 4He as measured using the vibration modes of a levitated drop". Physical Review B 66 (21). Bibcode 2002PhRvB..66u4504V. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.66.214504.

- ^ a b c d e Moore, Walter J. (1962). Physical Chemistry, 3rd ed. Prentice Hall.

- ^ a b c d e Adam, Neil Kensington (1941). The Physics and Chemistry of Surfaces, 3rd ed. Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b "Physical Properties Sources Index: Eötvös Constant". http://www.ppsi.ethz.ch/fmi/xsl/eqi/eqi_property_details_en.xsl?node_id=1113. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

- ^ G. Ertl, H. Knözinger and J. Weitkamp; Handbook of heterogeneous catalysis, Vol. 2, page 430; Wiley-VCH; Weinheim; 1997 ISBN 3-527-31241-2

- ^ Lange's Handbook of Chemistry (1967) 10th ed. pp 1661–1665 ISBN 0070161909 (11th ed.)

External links

- On surface tension and interesting real-world cases

- MIT Lecture Notes on Surface Tension

- Surface Tensions of Various Liquids

- Calculation of temperature-dependent surface tensions for some common components

- Surface Tension Calculator For Aqueous Solutions Containing the Ions H+, NH4+, Na+, K+, Mg2+, Ca2+, SO42–, NO3–, Cl–, CO32–, Br– and OH–.

- The Bubble Wall (Audio slideshow from the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory explaining cohesion, surface tension and hydrogen bonds)

|

|||||

is the liquid-solid surface tension,

is the liquid-solid surface tension, is the solid-air surface tension,

is the solid-air surface tension,