Supergravity

| Beyond the Standard Model |

|---|

| Standard Model |

|

|

In theoretical physics, supergravity (supergravity theory) is a field theory that combines the principles of supersymmetry and general relativity. Together, these imply that, in supergravity, the supersymmetry is a local symmetry (in contrast to non-gravitational supersymmetric theories, such as the Minimal Supersymmetric Standard Model). Since the generators of supersymmetry (SUSY) are convoluted with the Poincaré group to form a Super-Poincaré algebra it is very natural to see that supergravity follows naturally from supersymmetry.[1]

Contents |

Gravitons

Like any field theory of gravity, a supergravity theory contains a spin-2 field whose quantum is the graviton. Supersymmetry requires the graviton field to have a superpartner. This field has spin 3/2 and its quantum is the gravitino. The number of gravitino fields is equal to the number of supersymmetries. Supergravity theories are often said to be the only consistent theories of interacting massless spin 3/2 fields.

History

Four-dimensional SUGRA

SUGRA, or SUper GRAvity, was initially proposed as a four-dimensional theory in 1976 by Daniel Z. Freedman, Peter van Nieuwenhuizen and Sergio Ferrara at Stony Brook University, but was quickly generalized to many different theories in various numbers of dimensions and greater number (N) of supersymmetry charges. Supergravity theories with N>1 are usually referred to as extended supergravity (SUEGRA). Some supergravity theories were shown to be equivalent to certain higher-dimensional supergravity theories via dimensional reduction (e.g. N = 1 11-dimensional supergravity is dimensionally reduced on S7 to N = 8, d = 4 SUGRA). The resulting theories were sometimes referred to as Kaluza-Klein theories, as Kaluza and Klein constructed, nearly a century ago, a five-dimensional gravitational theory, that when dimensionally reduced on circle, its 4-dimensional non-massive modes describe electromagnetism coupled to gravity.

mSUGRA

mSUGRA means minimal SUper GRAvity. The construction of a realistic model of particle interactions within the N = 1 supergravity framework where supersymmetry (SUSY) is broken by a super Higgs mechanism was carried out by Ali Chamseddine, Richard Arnowitt and Pran Nath in 1982. In these classes of models collectively now known as minimal supergravity Grand Unification Theories (mSUGRA GUT), gravity mediates the breaking of SUSY through the existence of a hidden sector. mSUGRA naturally generates the Soft SUSY breaking terms which are a consequence of the Super Higgs effect. Radiative breaking of electroweak symmetry through Renormalization Group Equations (RGEs) follows as an immediate consequence. mSUGRA is one of the most widely investigated models of particle physics due to it predictive power requiring only four input parameters and a sign, to determine the low energy Phenomenology from the scale of Grand Unification.

11d: the maximal SUGRA

One of these supergravities, the 11-dimensional theory, generated considerable excitement as the first potential candidate for the theory of everything. This excitement was built on four pillars, two of which have now been largely discredited:

- Werner Nahm showed that 11 dimensions was the largest number of dimensions consistent with a single graviton, and that a theory with more dimensions would also have particles with spins greater than 2. These problems are avoided in 12 dimensions if two of these dimensions are timelike, as has been often emphasized by Itzhak Bars.

- In 1981, Ed Witten showed that 11 was the smallest number of dimensions that was big enough to contain the gauge groups of the Standard Model, namely SU(3) for the strong interactions and SU(2) times U(1) for the electroweak interactions. Today many techniques exist to embed the standard model gauge group in supergravity in any number of dimensions. For example, in the mid and late 1980s one often used the obligatory gauge symmetry in type I and heterotic string theories. In type II string theory they could also be obtained by compactifying on certain Calabi-Yau manifolds. Today one may also use D-branes to engineer gauge symmetries.

- In 1978, Eugene Cremmer, Bernard Julia and Joel Scherk (CJS) found the classical action for an 11-dimensional supergravity theory. This remains today the only known classical 11-dimensional theory with local supersymmetry and no fields of spin higher than two. Other 11-dimensional theories are known that are quantum-mechanically inequivalent to the CJS theory, but classically equivalent (that is, they reduce to the CJS theory when one imposes the classical equations of motion). For example, in the mid 1980s Bernard de Wit and Hermann Nicolai found an alternate theory in D=11 Supergravity with Local SU(8) Invariance. This theory, while not manifestly Lorentz-invariant, is in many ways superior to the CJS theory in that, for example, it dimensionally-reduces to the 4-dimensional theory without recourse to the classical equations of motion.

- In 1980, Peter G. O. Freund and M. A. Rubin showed that compactification from 11 dimensions preserving all the SUSY generators could occur in two ways, leaving only 4 or 7 macroscopic dimensions (the other 7 or 4 being compact). Unfortunately, the noncompact dimensions have to form an anti-de Sitter space. Today it is understood that there are many possible compactifications, but that the Freund-Rubin compactifications are invariant under all of the supersymmetry transformations that preserve the action.

Thus, the first two results appeared to establish 11 dimensions uniquely, the third result appeared to specify the theory, and the last result explained why the observed universe appears to be four-dimensional.

Many of the details of the theory were fleshed out by Peter van Nieuwenhuizen, Sergio Ferrara and Daniel Z. Freedman.

The end of the SUGRA era

The initial excitement over 11-dimensional supergravity soon waned, as various failings were discovered, and attempts to repair the model failed as well. Problems included:

- The compact manifolds which were known at the time and which contained the standard model were not compatible with supersymmetry, and could not hold quarks or leptons. One suggestion was to replace the compact dimensions with the 7-sphere, with the symmetry group SO(8), or the squashed 7-sphere, with symmetry group SO(5) times SU(2).

- Until recently, the physical neutrinos seen in the real world were believed to be massless, and appeared to be left-handed, a phenomenon referred to as the chirality of the Standard Model. It was very difficult to construct a chiral fermion from a compactification — the compactified manifold needed to have singularities, but physics near singularities did not begin to be understood until the advent of orbifold conformal field theories in the late 1980s.

- Supergravity models generically result in an unrealistically large cosmological constant in four dimensions, and that constant is difficult to remove, and so require fine-tuning. This is still a problem today.

- Quantization of the theory led to quantum field theory gauge anomalies rendering the theory inconsistent. In the intervening years physicists have learned how to cancel these anomalies.

Some of these difficulties could be avoided by moving to a 10-dimensional theory involving superstrings. However, by moving to 10 dimensions one loses the sense of uniqueness of the 11-dimensional theory.

The core breakthrough for the 10-dimensional theory, known as the first superstring revolution, was a demonstration by Michael B. Green, John H. Schwarz and David Gross that there are only three supergravity models in 10 dimensions which have gauge symmetries and in which all of the gauge and gravitational anomalies cancel. These were theories built on the groups SO(32) and  , the direct product of two copies of E8. Today we know that, using D-branes for example, gauge symmetries can be introduced in other 10-dimensional theories as well. [2]

, the direct product of two copies of E8. Today we know that, using D-branes for example, gauge symmetries can be introduced in other 10-dimensional theories as well. [2]

The second superstring revolution

Initial excitement about the 10-dimensional theories, and the string theories that provide their quantum completion, died by the end of the 1980s. There were too many Calabi-Yaus to compactify on, many more than Yau had estimated, as he admitted in December 2005 at the 23rd International Solvay Conference in Physics. None quite gave the standard model, but it seemed as though one could get close with enough effort in many distinct ways. Plus no one understood the theory beyond the regime of applicability of string perturbation theory.

There was a comparatively quiet period at the beginning of the 1990s; however, several important tools were developed. For example, it became apparent that the various superstring theories were related by "string dualities", some of which relate weak string-coupling (i.e. perturbative) physics in one model with strong string-coupling (i.e. non-perturbative) in another.

Then it all changed, in what is known as the second superstring revolution. Joseph Polchinski realized that obscure string theory objects, called D-branes, which he had discovered six years earlier, are stringy versions of the p-branes that were known in supergravity theories. The treatment of these p-branes was not restricted by string perturbation theory; in fact, thanks to supersymmetry, p-branes in supergravity were understood well beyond the limits in which string theory was understood.

Armed with this new nonperturbative tool, Edward Witten and many others were able to show that all of the perturbative string theories were descriptions of different states in a single theory which he named M-theory. Furthermore he argued that the long wavelength limit* of M-theory should be described by the 11-dimensional supergravity that had fallen out of favor with the first superstring revolution 10 years earlier, accompanied by the 2- and 5-branes. [*= i.e. when the quantum wavelength associated to objects in the theory are much larger than the size of the 11th dimension].

Historically, then, supergravity has come "full circle". It is a commonly used framework in understanding features of string theories, M-theory and their compactifications to lower spacetime dimensions.

Relation to superstrings

Particular 10-dimensional supergravity theories are considered "low energy limits" of the 10-dimensional superstring theories; more precisely, these arise as the massless, tree-level approximation of string theories. True effective field theories of string theories, rather than truncations, are rarely available. Due to string dualities, the conjectured 11-dimensional M-theory is required to have 11-dimensional supergravity as a "low energy limit". However, this doesn't necessarily mean that string theory/M-theory is the only possible UV completion of supergravity; supergravity research is useful independent of those relations.

4D N = 1 SUGRA

Before we move on to SUGRA proper, let's recapitulate some important details about general relativity. We have a 4D differentiable manifold M with a Spin(3,1) principal bundle over it. This principal bundle represents the local Lorentz symmetry. In addition, we have a vector bundle T over the manifold with the fiber having four real dimensions and transforming as a vector under Spin(3,1). We have an invertible linear map from the tangent bundle TM to T. This map is the vierbein. The local Lorentz symmetry has a gauge connection associated with it, the spin connection.

The following discussion will be in superspace notation, as opposed to the component notation, which isn't manifestly covariant under SUSY. There are actually many different versions of SUGRA out there which are inequivalent in the sense that their actions and constraints upon the torsion tensor are different, but ultimately equivalent in that we can always perform a field redefinition of the supervierbeins and spin connection to get from one version to another.

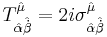

In 4D N=1 SUGRA, we have a 4|4 real differentiable supermanifold M, i.e. we have 4 real bosonic dimensions and 4 real fermionic dimensions. As in the nonsupersymmetric case, we have a Spin(3,1) principal bundle over M. We have an R4|4 vector bundle T over M. The fiber of T transforms under the local Lorentz group as follows; the four real bosonic dimensions transform as a vector and the four real fermionic dimensions transform as a Majorana spinor. This Majorana spinor can be reexpressed as a complex left-handed Weyl spinor and its complex conjugate right-handed Weyl spinor (they're not independent of each other). We also have a spin connection as before.

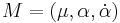

We will use the following conventions; the spatial (both bosonic and fermionic) indices will be indicated by M, N, ... . The bosonic spatial indices will be indicated by μ, ν, ..., the left-handed Weyl spatial indices by α, β,..., and the right-handed Weyl spatial indices by  ,

,  , ... . The indices for the fiber of T will follow a similar notation, except that they will be hatted like this:

, ... . The indices for the fiber of T will follow a similar notation, except that they will be hatted like this:  . See van der Waerden notation for more details.

. See van der Waerden notation for more details.  . The supervierbein is denoted by

. The supervierbein is denoted by  , and the spin connection by

, and the spin connection by  . The inverse supervierbein is denoted by

. The inverse supervierbein is denoted by  .

.

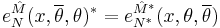

The supervierbein and spin connection are real in the sense that they satisfy the reality conditions

where

where  ,

,  , and

, and  and

and  .

.

The covariant derivative is defined as

![D_\hat{M}f=E^N_{\hat{M}}\left( \partial_N f %2B \omega_N[f] \right)](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/8f1314c80a90bbed7c8b886249c7eb73.png) .

.

The covariant exterior derivative as defined over supermanifolds needs to be super graded. This means that every time we interchange two fermionic indices, we pick up a +1 sign factor, instead of -1.

The presence or absence of R symmetries is optional, but if R-symmetry exists, the integrand over the full superspace has to have an R-charge of 0 and the integrand over chiral superspace has to have an R-charge of 2.

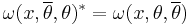

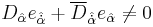

A chiral superfield X is a superfield which satisfies  . In order for this constraint to be consistent, we require the integrability conditions that

. In order for this constraint to be consistent, we require the integrability conditions that  for some coefficients c.

for some coefficients c.

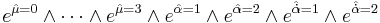

Unlike nonSUSY GR, the torsion has to be nonzero, at least with respect to the fermionic directions. Already, even in flat superspace,  . In one version of SUGRA (but certainly not the only one), we have the following constraints upon the torsion tensor:

. In one version of SUGRA (but certainly not the only one), we have the following constraints upon the torsion tensor:

Here,  is a shorthand notation to mean the index runs over either the left or right Weyl spinors.

is a shorthand notation to mean the index runs over either the left or right Weyl spinors.

The superdeterminant of the supervierbein,  , gives us the volume factor for M. Equivalently, we have the volume 4|4-superform

, gives us the volume factor for M. Equivalently, we have the volume 4|4-superform  .

.

If we complexify the superdiffeomorphisms, there is a gauge where  ,

,  and

and  . The resulting chiral superspace has the coordinates x and Θ.

. The resulting chiral superspace has the coordinates x and Θ.

R is a scalar valued chiral superfield derivable from the supervielbeins and spin connection. If f is any superfield,  is always a chiral superfield.

is always a chiral superfield.

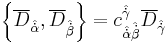

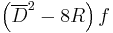

The action for a SUGRA theory with chiral superfields X, is given by

where K is the Kähler potential and W is the superpotential, and  is the chiral volume factor. Unlike the case for flat superspace, adding a constant to either the Kähler or superpotential is now physical. A constant shift to the Kähler potential changes the effective Planck constant, while a constant shift to the superpotential changes the effective cosmological constant. As the effective Planck constant now depends upon the value of the chiral superfield X, we need to rescale the supervierbeins (a field redefinition) to get a constant Planck constant. This is called the Einstein frame.

is the chiral volume factor. Unlike the case for flat superspace, adding a constant to either the Kähler or superpotential is now physical. A constant shift to the Kähler potential changes the effective Planck constant, while a constant shift to the superpotential changes the effective cosmological constant. As the effective Planck constant now depends upon the value of the chiral superfield X, we need to rescale the supervierbeins (a field redefinition) to get a constant Planck constant. This is called the Einstein frame.

Higher-dimensional SUGRA

See the article higher-dimensional supergravity for more details.

See also

- M-theory

- General relativity

- Supersymmetry

- Grand Unified Theory

- Super-Poincaré algebra

- Quantum mechanics

- Supermanifold

- String Theory

References

Historical

- ^ P. van Nieuwenhuizen, Phys. Rep. 68, 189 (1981)

- ^ Blumenhagen, R.; Cvetic, M.; Langacker, P.; Shiu, G. (2005). "Toward Realistic Intersecting D-Brane Models". arXiv:hep-th/0502005 [hep-th].

- D.Z. Freedman, P. van Nieuwenhuizen and S. Ferrara, "Progress Toward A Theory Of Supergravity", Physical Review D13 (1976) pp 3214–3218.

- E. Cremmer, B. Julia and J. Scherk, "Supergravity theory in eleven dimensions", Physics Letters B76 (1978) pp 409–412. scanned version

- P. Freund and M. Rubin, "Dynamics of dimensional reduction", Physics Letters B97 (1980) pp 233–235.

- Ali H. Chamseddine, R. Arnowitt, Pran Nath, "Locally Supersymmetric Grand Unification", " Phys. Rev.Lett.49:970,1982"

- Michael B. Green, John H. Schwarz, "Anomaly Cancellation in Supersymmetric D=10 Gauge Theory and Superstring Theory", Physics Letters B149 (1984) pp117–122.

General

- Bernard de Wit(2002) Supergravity

- A Supersymmetry primer [1] (1998) updated in (2006), (the user friendly guide).

- Adel Bilal, Introduction to supersymmetry (2001) ArXiv hep-th/0101055, (a comprehensive introduction to supersymmetry).

- Friedemann Brandt, Lectures on supergravity (2002) ArXiv hep-th/0204035, (an introduction to 4-dimensional N = 1 supergravity).

- Wess, Julius; Bagger, Jonathan (1992). Supersymmetry and Supergravity. Princeton University Press. pp. 260. ISBN 0691025304.

|

|||||||||

![S = \int d^4x d^2\Theta 2\mathcal{E}\left[ \frac{3}{8} \left( \overline{D}^2 - 8R \right) e^{-K(\overline{X},X)/3} %2B W(X) \right] %2B c.c.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/abff7de71afc73ad7d176fcf5ce0815c.png)