Hierarchy

A hierarchy (Greek: hierarchia (ἱεραρχία), from hierarches, "leader of sacred rites") is an arrangement of items (objects, names, values, categories, etc.) in which the items are represented as being "above," "below," or "at the same level as" one another. Abstractly, a hierarchy is simply an ordered set or an acyclic directed graph.

A hierarchy (sometimes abbreviated HR) can link entities either directly or indirectly, and either vertically or horizontally. The only direct links in a hierarchy, insofar as they are hierarchical, are to one's immediate superior or to one of one's subordinates, although a system that is largely hierarchical can also incorporate alternative hierarchies. Indirect hierarchical links can extend "vertically" upwards or downwards via multiple links in the same direction, following a path. All parts of the hierarchy which are not linked vertically to one another nevertheless can be "horizontally" linked through a path by traveling up the hierarchy to find a common direct or indirect superior, and then down again. This is akin to two co-workers or colleagues; each reports to a common superior, but they have the same relative amount of authority. Organizational forms exist that are both alternative and complimentary to hierarchy. Heterarchy (sometimes abbreviated HT) is one such form.

Terminology

Hierarchies have their own special vocabulary. These terms are easiest to understand when a hierarchy is diagrammed (see below).

The generic hierarchy uses the following terms:[1][2]

- Object: one entity (e.g., a person, department or concept) or element of arrangement or member of a set

- System: the entire set of objects that are being arranged hierarchically (e.g., an administration)

- Dimension: another word for "system" from on-line analytical processing (e.g. cubes)

- Member: an (element or object) in a (system or dimension) at any (level or rank)

- Rank: the relative value, worth, complexity, power, importance, authority, level etc. of an object

- Level: a set of objects with the same rank OR importance

- Ordering: the arrangement of the (ranks or levels)

- Hierarchy: the arrangement of a particular set of (ranks or levels) i.e. multiple hierarchies are possible per (dimension or system)

- Collection: all of the objects at one level

- Superior: a higher level or an object ranked at a higher level (parent or ancestor)

- Subordinate: a lower level or an object ranked at a lower level (child or descendent)

- Hierarch, the top level of the hierarchy, usually consisting of one object or member of a dimension

- Peer: an object with the same rank (and therefore at the same level)

- Neighbour: the adjacent level/ranking (the immediate superior and immediate inferior)

- Interaction: the relationship between an object and its direct superior or subordinate (i.e. a superior/inferior pair)

- a direct interaction occurs when one object is on a level exactly one higher or one lower than the other (i.e., on a tree, the two objects have a line between them)

- Distance: the minimum number of connections between two objects, i.e., one less than the number of objects that need to be "crossed" to trace a path from one object to another

- Span: a qualitative description of the width of a level when diagrammed, i.e., the number of subordinates an object has

(N.B., while hierarchies are commonly studied using graph theory, the general terminology used is different, and words such as "direct" may have different general meanings)

Most hierarchies use a more specific vocabulary pertaining to their subject, but the idea behind them is the same. For example, with data structures, objects are known as nodes, superiors are called parents and subordinates are called children. In a business setting, a superior is a supervisor/boss and a peer is a colleague.

Degree of branching

Degree of branching refers to the number of direct subordinates or children an object has (equivalent to the number of vertices a node has). Hierarchies can be categorized based on the "maximum degree", the highest degree present in the system as a whole. Categorization in this way yields two broad classes: linear and branching.

In a linear hierarchy, the maximum degree is 1.[1] In other words, all of the objects can be visualized in a lineup, and each object (excluding the top and bottom ones) has exactly one direct subordinate and one direct superior. Note that this is referring to the objects and not the levels; every hierarchy has this property with respect to levels, but normally each level can have an infinite number of objects. An example of a linear hierarchy is the hierarchy of life.

In a branching hierarchy, one or more objects has a degree of 2 or more (and therefore the maximum degree is 2 or higher).[1] For many people, the word "hierarchy" automatically evokes an image of a branching hierarchy.[1] Branching hierarchies are present within numerous systems, including organizations and classification schemes. The broad category of branching hierarchies can be further subdivided based on the degree.

A flat hierarchy is a branching hierarchy in which the maximum degree approaches infinity, i.e., with a wide span.[2] Most often, systems intuitively regarded as hierarchical have at most a moderate span. Therefore, a flat hierarchy is often not viewed as a hierarchy at all at first blush. For example, diamonds and graphite is a flat hierarchy of numerous carbon atoms which can be further decomposed into subatomic particles.

An overlapping hierarchy is a branching hierarchy in which at least one object has two parent objects.[1] For example, a graduate student can have two co-supervisors to whom the student reports directly and equally, and who have the same level of authority within the university hierarchy (i.e., they have the same position or tenure status

History of the term

The first use of the English word "hierarchy" cited by the Oxford English Dictionary was in 1880, when it was used in reference to the three orders of three angels as depicted by Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (5th–6th centuries). Pseudo-Dionysius used the related Latin word (hierarchia) both in reference to the celestial hierarchy and the ecclesiastical hierarchy.[3] His term is derived from the Greek term "ἱεραρχία" meaning "rule by priests" (from "ἱεράρχης" – ierarches, meaning "president of sacred rites, high-priest"[4] and that from "ἱερεύς" – iereus, "priest"[5] + "ἀρχή" – arche, amongst others "first place or power, rule"[6]), and Dionysius is credited with first use of it as an abstract noun. Since hierarchical churches, such as the Roman Catholic (see Catholic Church hierarchy) and Eastern Orthodox churches, had tables of organization that were "hierarchical" in the modern sense of the word (traditionally with God as the pinnacle or head of the hierarchy), the term came to refer to similar organizational methods in secular settings.

Visualization

A hierarchy is typically depicted as a pyramid, where the height of a level represents that level's status and width of a level represents the quantity of items at that level relative to the whole. For example, the few Directors of a company could be at the apex, and the base could be thousands of people who have no subordinates.

These pyramids are typically diagrammed with a tree or triangle diagram (but note that not all triangle/pyramid diagrams are hierarchical), both of which serve to emphasize the size differences between the levels. An example of a triangle diagram appears to the right. An organizational chart is the diagram of a hierarchy within an organization, and is depicted in tree form below.

More recently, as computers have allowed the storage and navigation of ever larger data sets, various methods have been developed to represent hierarchies in a manner that makes more efficient use of the available space on a computer's screen. Examples include fractal maps, TreeMaps and Radial Trees.

Informal representation

In plain English, a hierarchy can be thought of as a set in which:[1]

- No element is superior to itself, and

- One element, the hierarch, is superior to all of the other elements in the set.

The first requirement is also interpreted to mean that a hierarchy can have no circular relationships; the association between two objects is always transitive. The second requirement asserts that a hierarchy must have a leader or root that is common to all of the objects.

Mathematical representation

Mathematically, in its most general form, a hierarchy is a partially ordered set or poset.[7] The system in this case is the entire poset, which is constituted of elements. Within this system, each element shares a particular unambiguous property. Objects with the same property value are grouped together, and each of those resulting levels is referred to as a class.

"Hierarchy" is particularly used to refer to a poset in which the classes are organized in terms of increasing complexity.

Subtypes

Nested hierarchy

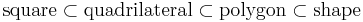

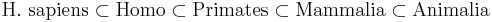

A nested hierarchy or inclusion hierarchy is a hierarchical ordering of nested sets.[8] The concept of nesting is exemplified in Russian matryoshka dolls. Each doll is encompassed by another doll, all the way to the outer doll. The outer doll holds all of the inner dolls, the next outer doll holds all the remaining inner dolls, and so on. Matryoshkas represent a nested hierarchy where each level contains only one object, i.e., there is only one of each size of doll; a generalized nested hierarchy allows for multiple objects within levels but with each object having only one parent at each level. The general concept is both demonstrated and mathematically formulated in the following example:

A square can always also be referred to as a quadrilateral, polygon or shape. In this way, it is a hierarchy. However, consider the set of polygons using this classification. A square can only be a quadrilateral; it can never be a triangle, hexagon, etc.

Nested hierarchies are the organizational schemes behind taxonomies and systematic classifications. For example, using the original Linnaean taxonomy (the version he laid out in the 10th edition of Systema Naturae), a human can be formulated as:[9]

Taxonomies may change frequently (as seen in biological taxonomy), but the underlying concept of nested hierarchies is always the same.

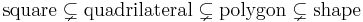

Containment hierarchy

A containment hierarchy is a direct extrapolation of the nested hierarchy concept. All of the ordered sets are still nested, but every set must be "strict"—no two sets can be identical. The shapes example above can be modified to demonstrate this:

The notation  means x is a subset of y but is not equal to y.

means x is a subset of y but is not equal to y.

A general example of a containment hierarchy is demonstrated in class inheritance in object-oriented programming.

Two types of containment hierarchies are the subsumptive containment hierarchy and the compositional containment hierarchy. A subsumptive hierarchy "subsumes" its children, and a compositional hierarchy is "composed" of its children. A hierarchy can also be both subsumptive and compositional.[10]

Subsumptive containment hierarchy

A subsumptive containment hierarchy is a classification of objects from the general to the specific. Other names for this type of hierarchy are "compositional hierarchy", "taxonomic hierarchy" and "IS-A hierarchy".[7][11][12] The last term describes the relationship between each level—a lower-level object "is a" member of the higher class. The taxonomical structure outlined above is a subsumptive containment hierarchy, as are all systematic naming schemes. Using again the example of Linnaean taxonomy, it can be seen that an object that is part of the level Mammalia "is a" member of the level Animalia; more specifically, a human "is a" primate, a primate "is a" mammal, and so on. A subsumptive hierarchy can also be defined abstractly as a hierarchy of "concepts".[12] For example, with the Linnaean hierarchy outlined above, an entity name like Animalia is a way to group all the species that fit the conceptualization of an animal.

Compositional containment hierarchy

A compositional containment hierarchy is an ordering of the parts that make up a system—the system is "composed" of these parts.[13] Most engineered structures, whether natural or artificial, can be broken down in this manner.

The compositional hierarchy that every person encounters at every moment is the hierarchy of life. Every person can be reduced to organ systems, which are composed of organs, which are composed of tissues, which are composed of cells, which are composed of molecules, which are composed of atoms. In fact, the last two levels apply to all matter, at least at the macroscopic scale. Moreover, each of these levels inherit all the properties of their children.

In this particular example, there are also emergent properties—functions that are not seen at the lower level (e.g., cognition is not a property of neurons but is of the brain)—and a scalar quality (molecules are bigger than atoms, cells are bigger than molecules, etc.). Both of these concepts commonly exist in compositional hierarchies, but they are not a required general property. These level hierarchies are characterized by bi-directional causation.[8] Upward causation involves lower-level entities causing some property of a higher level entity; children entities may interact to yield parent entities, and parents are composed at least partly by their children. Downward causation refers to the effect that the incorporation of entity x into a higher-level entity can have on x's properties and interactions. Furthermore, the entities found at each level are autonomous.

Contexts and applications

Almost every system within the world is arranged hierarchically.[14] By their common definitions, every nation has a government and every government is hierarchical.[15][16] Socioeconomic systems are stratified into a social hierarchy (the social stratification of societies), and all systematic classification schemes (taxonomies) are hierarchical. Most organized religions, regardless of their internal governance structures, operate as a hierarchy under God. Many Christian denominations have an autocephalous ecclesiastical hierarchy of leadership. Families are viewed as a hierarchical structure in terms of cousinship (e.g., first cousin once removed, second cousin, etc.), ancestry (as depicted in a family tree) and inheritance (succession and heirship). All the requisites of a well-rounded life and lifestyle can be organized using Maslow's hierarchy of human needs. Learning must often follow a hierarchical scheme—to learn differential equations one must first learn calculus; to learn calculus one must first learn elementary algebra; and so on. Even nature itself has its own hierarchies, as demonstrated in numerous schemes such as Linnaean taxonomy, the organization of life, and biomass pyramids. Hierarchies are so infused into daily life that they are viewed as trivial.[1][14]

While the above examples are often clearly depicted in a hierarchical form and are classic examples, hierarchies exist in numerous systems where this branching structure is not immediately apparent. For example, all postal code systems are necessarily hierarchical. Using the Canadian postal code system, the top level's binding concept is the "postal district", and consists of 18 objects (letters). The next level down is the "zone", where the objects are the digits 0–9. This is an example of an overlapping hierarchy, because each of these 10 objects has 18 parents. The hierarchy continues downward to generate, in theory, 7,200,000 unique codes of the format A0A 0A0. Most library classification systems are also hierarchical. The Dewey Decimal System is regarded as infinitely hierarchical because there is no finite bound on the number of digits can be used after the decimal point.[17]

Organizations

Organizations can be structured using a hierarchy. In an organizational hierarchy, there is a single person or group with the most power and authority, and each subsequent level represents a lesser authority. Most organizations are structured in this manner, including governments, companies, militia and organized religions. The units or persons within an organization are depicted hierarchically in an organizational chart.

In a reverse hierarchy, the conceptual pyramid of authority is turned upside-down, so that the apex is at the bottom and the base is at the top. This model represents the idea that members of the higher rankings are responsible for the members of the lower rankings.

Computer graphic imaging (CGI)

Within most CGI and computer animation programs is the use of hierarchies. On a 3D model of a human, the chest is a parent of the upper left arm, which is a parent of the lower left arm, which is a parent of the hand. This is used in modeling and animation of almost everything built as a 3D digital model.

Hierarchical verbal alignment

In some languages, such as Cree and Mapudungun, subject and object on verbs are distinguished not by different subject and object markers, but via a hierarchy of persons.

In this system, the three (or four with Algonquian languages) persons are placed in a hierarchy of salience. To distinguish which is subject and which object, inverse markers are used if the object outranks the subject.

In music, the structure of a composition is often understood hierarchically (for example by Heinrich Schenker (1768–1835, see Schenkerian analysis), and in the (1985) Generative Theory of Tonal Music, by composer Fred Lerdahl and linguist Ray Jackendoff). The sum of all notes in a piece is understood to be an all-inclusive surface, which can be reduced to successively more sparse and more fundamental types of motion. The levels of structure that operate in Schenker's theory are the foreground, which is seen in all the details of the musical score; the middle ground, which is roughly a summary of an essential contrapuntal progression and voice-leading; and the background or Ursatz, which is one of only a few basic "long-range counterpoint" structures that are shared in the gamut of tonal music literature.

The pitches and form of tonal music are organized hierarchically, all pitches deriving their importance from their relationship to a tonic key, and secondary themes in other keys are brought back to the tonic in a recapitulation of the primary theme. Susan McClary connects this specifically in the sonata-allegro form to the feminist hierarchy of gender (see above) in her book Feminine Endings, even pointing out that primary themes were often previously called "masculine" and secondary themes "feminine."

Ethics, behavioral psychology, philosophies of identity

In ethics, various virtues are enumerated and sometimes organized hierarchically according to certain brands of virtue theory.

In all of these random examples, there is an asymmetry of 'compositional' significance between levels of structure, so that small parts of the whole hierarchical array depend, for their meaning, on their membership in larger parts.

In the work of diverse theorists such as William James (1842–1910), Michel Foucault (1926–1984) and Hayden White, important critiques of hierarchical epistemology are advanced. James famously asserts in his work "Radical Empiricism" that clear distinctions of type and category are a constant but unwritten goal of scientific reasoning, so that when they are discovered, success is declared. But if aspects of the world are organized differently, involving inherent and intractable ambiguities, then scientific questions are often considered unresolved.

Feminists, Marxists, anarchists, communists, critical theorists and others, all of whom have multiple interpretations, criticize the hierarchies commonly found within human society, especially in social relationships. Hierarchies are present in all parts of society: in businesses, schools, families, etc. These relationships are often viewed as necessary. However, feminists, Marxists, critical theorists and others analyze hierarchy in terms of the values and power that it arbitrarily assigns to one group over another.

Further applications

Information-based |

City planning-based |

Linguistics-based |

Power- or authority-based

|

Value-based |

Perception-based |

Religion- and mythology-based

- Levels of consciousness

- Levels of spiritual development

- In Therevada Buddhism

- In Mahayana Buddhism

- In Theosophy

- Ages in the evolution of society

- Degrees of communion between various Christian churches

- UFO religions

- Deities

- In Japanese Buddhism

- In Theosophy

- Angels

- In Christianity

- In Judaism

- In Islam

- In Zoroastrianism

- Devils and Demons

- Hells

- Religions in society

- (organizational hierarchies are listed under "Power- or authority-based")

Methods using the hierarchical model

- Analytic Hierarchy Process

- Hierarchic Object-Oriented Design

- Hierarchical Bayes model

- Hierarchical clustering

- Hierarchical constraint satisfaction

- Hierarchical linear modeling

- Hierarchical modulation

- Hierarchical proportion

- Hierarchical radial basis function

- Hierarchical storage management

- Hierarchical task network

- Hierarchical temporal memory

- Hierarchical token bucket

- Hierarchical visitor pattern

- Presentation-abstraction-control

See also

- Form of government

- Graph theory

- Heterarchy

- Hierarch

- Hierarchical classifier

- Hierarchical epistemology

- Hierarchical hidden Markov model

- Hierarchical incompetence

- Hierarchical INTegration

- Hierarchical Music Specification Language

- Hierarchical protection domains

- Hierarchy Open Service Interface Definition

- Hierarchy problem

- HierarchyBrowser

- Multilevel model

- Peter Principle

Footnotes

- ^ a b c d e f g Dawkins, Richard (1976). "Hierarchical organization: a candidate principle for ethology". In Bateson, Paul Patrick Gordon; Hinde, Robert A.. Growing points in ethology: based on a conference sponsored by St. John's College and King's College, Cambridge. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 7–54. ISBN 0521290864.

- ^ a b Simon, Herbert A. (12 December 1962). "The Architecture of Complexity". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: American Philosophical Society) 106 (6): 467–482. ISSN 0003-049X.

- ^ CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Hierarchy

- ^ ἱεράρχης, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ^ ἱερεύς, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ^ ἀρχή, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ^ a b Lehmann, Fritz (1996). "Big Posets of Participatings and Thematic Roles". In Eklund, Peter G.; Ellis, Gerard; Mann, Graham. Conceptual structures: knowledge representation as interlingua—4th International Conference on Conceptual Structures, ICCS '96, Sydney, Australia, August 19–22, 1996—proceedings. Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence 115. Germany: Springer. pp. 50–74. ISBN 3540615342.

- ^ a b Lane, David (2006). "Hierarchy, Complexity, Society". In Pumain, Denise. Hierarchy in Natural and Social Sciences. New York, New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 81–120. ISBN 9781402041266.

- ^ Linnaei, Carl von (1959) (in Latin). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae :secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (10th ed.). Holmiae: Impensis Direct. ISBN 0665530080. http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/542#. Retrieved 2011-09-24.

- ^ Kopisch, Manfred; Günther, Andreas (1992). "Industrial and Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence and Expert Systems". In Belli, Fevzi. Industrial and engineering applications of artificial intelligence and expert systems: 5th international conference, IEA/AIE-92, Paderborn, Germany, June 9–12, 1992 : proceedings. Lecture Notes in Computer Science Series. 602. Springer. pp. 424–427. doi:10.1007/BFb0024994. ISBN 354055601X. ISSN 0302-9743.

- ^ "Compositional hierarchy". WebSphere Transformation Extender Design Studio. http://publib.boulder.ibm.com/infocenter/wtxdoc/v8r2m0/index.jsp?topic=/com.ibm.websphere.dtx.md.doc/concepts/c_map_design_Compositional_Hierarchy.htm. Retrieved 9 October 2009.

- ^ a b Funke, Birger; Sebastian, Hans-Jürgen (1999). "An advanced modeling environment based on a hybrid AI-OR approach". In Polis, Michael P.; Dontchev, Asen L.; Kall, Peter; Lascieka, Irena; Olbrot, Andrzej W.. Systems modelling and optimization: proceedings of the 18th IFIP TC7 conference. Research notes in mathematics series. 396. CRC Press. ISBN 0849306078.

- ^ Parsons, David (2002). Object Oriented Programming in C++. Cengage Learning. pp. 110–185. ISBN 0826454283.

- ^ a b Kulish, V. V. (2002). Hierarchical Methods: Hierarchy and hierarchical asymptotic methods in electrodynamics. 1. Springer. pp. xvii-xx; 49–71. ISBN 1402007574.

- ^ "government". Compact Oxford English Dictionary. 1991. ISBN 9780198610229. http://www.askoxford.com/concise_oed/government?view=uk.

- ^ "nation". Compact Oxford English Dictionary. 1991. ISBN 9780198610229. http://www.askoxford.com/concise_oed/nation?view=uk.

- ^ Walker, Randy (May/June 2009). "Tracking Nuclear Sources" (PDF). Well Servicing: 28–30. http://wellservicingmagazine.com/sites/default/files/pdfmag/WSM_MAYJUN09.PDF. See also Wikipedia article.

Further reading

- Ahl, Valerie; Allen, Timothy F. H. (1996). Hierarchy Theory. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231084811.

- Akl, Selim G.; Taylor, Peter D. (1983). "Cryptographic solution to a multilevel security problem" (PDF). Advances in Cryptology: Proceedings of CRYPTO '82. New York: Plenum Publishing Corporation. pp. 237–249. ISBN 0306413663. http://dsns.csie.nctu.edu.tw/research/crypto/HTML/PDF/C82/237.PDF.

- Ckurshumova, Wenzislava (2007). written at University of Toronto. "Regulatory hierarchies in auxin signal transduction and vascular tissue development" (Ph.D. dissertation). Dissertation Abstracts International 68 (5): section B. ISBN 9780494276822.

- Galindo, Cipriano; Fernández-Madrigal, Juan-Antonio (2007). Kacprzyk, Janusz. ed. Multiple Abstraction Hierarchies for Mobile Robot Operation in Large Environments. Studies in Computational Intelligence. Berlin: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. ISBN 978-3-540-72688-3.

- Nelson, Julie (1992). "Gender, Metaphor and the Definition of Economics". Economics and Philosophy 8: 103–125. doi:10.1017/S026626710000050X.

- Pumain, Diane (2006). Hierarchy in Natural and Social Sciences. New York, New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 9781402041266.

- Rosenbaum, A. (1999) (in French). Les représentations hiérarchiques en philosophie. Paris: Desclee de Brouwer.

- Shahbaba, Babak (2007). written at University of Toronto. "Improving classification models when a class hierarchy is available" (Ph.D. dissertation). Dissertation Abstracts International 68 (6): section B. ISBN 9780494280768.

- Also includes full copies of:

- Shahbaba, Babak; Neal, Radford M. (2007). "Improving Classification When a Class Hierarchy is Available Using a Hierarchy-Based Prior" (PDF). Bayesian Analysis (Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: International Society for Bayesian Analysis) 2 (1): 221–228. ISSN 1936-0975. http://ba.stat.cmu.edu/journal/2007/vol02/issue01/shahbaba.pdf.

- Shahbaba, Babak; Neal, Radford M. (2006). "Gene function classification using Bayesian models with hierarchy-based priors". BMC Bioinformatics (London, England: BioMed Central) 7: 448. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-7-448. ISBN 1471-2105. PMC 1618412. PMID 17038174. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1618412.

External links

- Principles and annotated bibliography of hierarchy theory

- Summary of the Principles of Hierarchy Theory — S.N. Salthe

- Everything is Hierarchical - Think in a different way.