Squeeze mapping

In linear algebra, a squeeze mapping is a type of linear map that preserves Euclidean area of regions in the Cartesian plane, but is not a Euclidean motion.

For a fixed positive real number r, the mapping

- (x,y) → (r x, y / r )

is the squeeze mapping with parameter r. Since

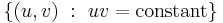

is a hyperbola, if u = r x and v = y / r, then uv = xy and the points of the image of the squeeze mapping are on the same hyperbola as (x,y) is. For this reason it is natural to think of the squeeze mapping as a hyperbolic rotation, as did Émile Borel in 1913, by analogy with circular rotations which preserves circles.

Contents |

Group theory

If r and s are positive real numbers, the composition of their squeeze mappings is the squeeze mapping of their product. Therefore the collection of squeeze mappings forms a one-parameter group isomorphic to the multiplicative group of positive real numbers. An additive view of this group arises from consideration of hyperbolic sectors and hyperbolic angles. In fact, the invariant measure of this group is hyperbolic angle.

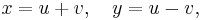

From the point of view of the classical groups, the group of squeeze mappings is SO+(1,1), the identity component of the indefinite orthogonal group of 2 × 2 real matrices preserving the quadratic form  This is equivalent to preserving the form

This is equivalent to preserving the form  via the change of basis

via the change of basis  and corresponds geometrically to preserving hyperbolae. The perspective of the group of squeeze mappings as hyperbolic rotation is analogous to interpreting the group SO(2) (the connected component of the definite orthogonal group) preserving quadratic form

and corresponds geometrically to preserving hyperbolae. The perspective of the group of squeeze mappings as hyperbolic rotation is analogous to interpreting the group SO(2) (the connected component of the definite orthogonal group) preserving quadratic form  ) as being circular rotations.

) as being circular rotations.

Note that the "SO+" notation corresponds to the fact that the reflections  and

and  are not allowed, though they preserve the form (in terms of x and y these are

are not allowed, though they preserve the form (in terms of x and y these are  and

and  ); the additional "+" in the hyperbolic case (as compared with the circular case) is necessary to specify the identity component because the group O(1,1) has 4 connected components, while the group O(2) has 2 components: SO(1,1) has 2 components, while SO(2) only has 1. The fact that the squeeze transforms preserve area and orientation corresponds to the inclusion of subgroups

); the additional "+" in the hyperbolic case (as compared with the circular case) is necessary to specify the identity component because the group O(1,1) has 4 connected components, while the group O(2) has 2 components: SO(1,1) has 2 components, while SO(2) only has 1. The fact that the squeeze transforms preserve area and orientation corresponds to the inclusion of subgroups  – in this case SO(1,1) ⊂ SL(2) – of the subgroup of hyperbolic rotations in the special linear group of transforms preserving area and orientation (a volume form). In the language of Möbius transforms, the squeeze transformations are the hyperbolic elements in the classification of elements.

– in this case SO(1,1) ⊂ SL(2) – of the subgroup of hyperbolic rotations in the special linear group of transforms preserving area and orientation (a volume form). In the language of Möbius transforms, the squeeze transformations are the hyperbolic elements in the classification of elements.

Literature

Among the earliest recognition of a squeeze symmetry was the 1647 discovery by Grégoire de Saint-Vincent that the area under a hyperbola (concretely, the curve given by xy = k) is the same over [a,b] as over [c,d] when a/b = c/d – this corresponds to the area under a hyperbola being preserved under hyperbolic rotation, and was a key step in the development of the logarithm. Formalization of the squeeze group required the theory of groups, which was not developed until the 19th century.

William Kingdon Clifford was the author of Common Sense and the Exact Sciences, published in 1885. In the third chapter on Quantity he discusses area in three sections. Clifford uses the term "stretch" for magnification and the term "squeeze" for contraction. Taking a given square area as fundamental, Clifford relates other areas by stretch and squeeze. He develops this calculus to the point of illustrating the addition of fractions in these terms in the second section. The third section is concerned with shear mapping as area-preserving.

The myth of Procrustes is linked with this mapping in a 1967 educational (SMSG) publication:

- Among the linear transformations, we have considered similarities, which preserve ratios of distances, but have not touched upon the more bizarre varieties, such as the Procrustean stretch (which changes a circle into an ellipse of the same area).

- Coxeter & Greitzer, pp. 100, 101.

Attention had been drawn to this plane mapping by Modenov and Parkhomenko in their Russian book of 1961 which was translated in 1967 by Michael B. P. Slater. It included a diagram showing the squeezing of a circle into an ellipse.

Werner Greub of the University of Toronto includes "pseudo-Euclidean rotation" in the chapter on symmetric bilinear functions of his text on linear algebra. This treatment in 1967 includes in short order both the diagonal form and the form with sinh and cosh.

The Mathematisch Centrum Amsterdam published E.R. Paërl's Representations of the Lorentz group and Projective Geometry in 1969. The squeeze mapping, written as a 2 × 2 diagonal matrix, Paërl calls a "hyperbolic screw".

In his 1999 monograph Classical Invariant Theory, Peter Olver discusses GL(2,R) and calls the group of squeeze mappings by the name the isobaric subgroup. However, in his 1986 book Applications of Lie Groups to Differential Equations (p. 127) he uses the term "hyperbolic rotation" for an equivalent mapping.

In 2004 the American Mathematical Society published Transformation Groups for Beginners by S.V. Duzhin and B.D. Chebotarevsky which mentions hyperbolic rotation on page 225. There the parameter r is given as et and the transformation group of squeeze mappings is used to illustrate the invariance of a differential equation under the group operation.

Applications

In studying linear algebra there are the purely abstract applications such as illustration of the singular-value decomposition or in the important role of the squeeze mapping in the structure of 2 × 2 real matrices. These applications are somewhat bland compared to two physical and a philosophical application.

Corner flow

In fluid dynamics one of the fundamental motions of an incompressible flow involves bifurcation of a flow running up against an immovable wall. Representing the wall by the axis y = 0 and taking the parameter r = exp(t) where t is time, then the squeeze mapping with parameter r applied to an initial fluid state produces a flow with bifurcation left and right of the axis x = 0. The same model gives fluid convergence when time is run backward. Indeed, the area of any hyperbolic sector is invariant under squeezing.

For another approach to a flow with hyperbolic streamlines, see the article potential flow, section "Power law with n = 2".

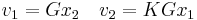

In 1989 Ottino described the "linear isochoric two-dimensional flow" as

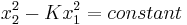

where K lies in the interval [−1,1]. The streamlines follow the curves

so negative K corresponds to an ellipse and positive K to a hyperbola, with the rectangular case of the squeeze mapping corresponding to K = 1.

Stocker and Hosoi (2004) announced their approach to corner flow as follows:

- we suggest an alternative formulation to account for the corner-like geometry, based on the use of hyperbolic coordinates, which allows substantial analytical progress towards determination of the flow in a Plateau border and attached liquid threads. We consider a region of flow forming an angle of π/2 and delimited on the left and bottom by symmetry planes.

Stocker and Hosoi then recall H.K. Moffatt's 1964 paper "Viscous and resistive eddies near a sharp corner" (Journal of Fluid Mechanics 18:1–18). Moffatt considers "flow in a corner between rigid boundaries, induced by an arbitrary disturbance at a large distance." According to Stocker and Hosoi,

- For a free fluid in a square corner, Moffatt's (antisymmetric) stream function ... [indicates] that hyperbolic coordinates are indeed the natural choice to describe these flows.

Relativistic spacetime

Select (0,0) for a "here and now" in a spacetime. Light radiant left and right through this central event tracks two lines in the spacetime, lines that can be used to give coordinates to events away from (0,0). Trajectories of lesser velocity track closer to the original timeline (0,t). Any such velocity can be viewed as a zero velocity under a squeeze mapping called a Lorentz boost. This insight follows from a study of split-complex number multiplications and the "diagonal basis" which corresponds to the pair of light lines. Formally, a squeeze preserves the hyperbolic metric expressed in the form  ; in a different coordinate system. This application in the Theory of relativity was noted in 1912 by Wilson and Lewis (see footnote p. 401 of reference),by Werner Greub in the 1960s, and in 1985 by Louis Kauffman. Furthermore, Wolfgang Rindler, in his popular textbook on relativity, used the squeeze mapping form of Lorentz transformations in his demonstration of their characteristic property (see equation 29.5 on page 45 of the 1969 edition, or equation 2.17 on page 37 of the 1977 edition, or equation 2.16 on page 52 of the 2001 edition).

; in a different coordinate system. This application in the Theory of relativity was noted in 1912 by Wilson and Lewis (see footnote p. 401 of reference),by Werner Greub in the 1960s, and in 1985 by Louis Kauffman. Furthermore, Wolfgang Rindler, in his popular textbook on relativity, used the squeeze mapping form of Lorentz transformations in his demonstration of their characteristic property (see equation 29.5 on page 45 of the 1969 edition, or equation 2.17 on page 37 of the 1977 edition, or equation 2.16 on page 52 of the 2001 edition).

Bridge to transcendentals

The area-preserving property of squeeze mapping has an application in setting the foundation of the transcendental functions natural logarithm and its inverse the exponential function:

Definition: Sector(a,b) is the hyperbolic sector obtained with central rays to (a, 1/a) and (b, 1/b).

Lemma: If bc = ad, then there is a squeeze mapping that moves the sector(a,b) to sector(c,d).

Proof: Take parameter r = c/a so that (u,v) = (rx, y/r) takes (a, 1/a) to (c, 1/c) and (b, 1/b) to (d, 1/d).

Theorem (Gregoire de Saint-Vincent 1647) If bc = ad , then the quadrature of the hyperbola xy = 1 against the asymptote has equal areas between a and b compared to between c and d.

Proof: An argument adding and subtracting triangles of area ½, one triangle being {(0,0), (0,1), (1,1)}, shows the hyperbolic sector area is equal to the area along the asymptote. The theorem then follows from the lemma.

Theorem (Alphonse Antonio de Sarasa 1649) As area measured against the asymptote increases in arithmetic progression, the projections upon the asymptote increase in geometric sequence. Thus the areas form logarithms of the asymptote index.

For instance, for a standard position angle which runs from (1, 1) to (x, 1/x), one may ask "When is the hyperbolic angle equal to one?" The answer is the transcendental number x = e (mathematical constant).

A squeeze with r = e moves the unit angle to one between (e, 1/e) and (ee, 1/ee) which subtends a sector also of area one. The geometric progression

- e, e2, e3, ..., en, ...

corresponds to the asymptotic index achieved with each sum of areas

- 1,2,3, ..., n,...

which is a proto-typical arithmetic progression A + nd where A = 0 and d = 1 .

See also

References

- HSM Coxeter & SL Greitzer (1967) Geometry Revisited, Chapter 4 Transformations, A genealogy of transformation.

- Edwin Bidwell Wilson & Gilbert N. Lewis (1912) "The space-time manifold of relativity. The non-Euclidean geometry of mechanics and electromagnetics", Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 48:387–507.

- W. H. Greub (1967) Linear Algebra, Springer-Verlag. See pages 272 to 274.

- Louis Kauffman (1985) "Transformations in Special Relativity", International Journal of Theoretical Physics 24:223–36.

- P. S. Modenov and A. S. Parkhomenko (1965) Geometric Transformations, volume one. See pages 104 to 106.

- J. M. Ottino (1989) The Kinematics of Mixing: stretching, chaos, transport, page 29, Cambridge University Press.

- Walter, Scott (1999). "The non-Euclidean style of Minkowskian relativity". In J. Gray. The Symbolic Universe: Geometry and Physics. Oxford University Press. pp. 91–127. http://www.univ-nancy2.fr/DepPhilo/walter/papers/nes.pdf.(see page 9 of e-link)

- Roman Stocker & A.E. Hosoi (2004) "Corner flow in free liquid films", Journal of Engineering Mathematics 50:267–88.