Spin group

| Group theory |

|---|

| Group theory |

|

Cyclic group Zn

Symmetric group, Sn Dihedral group, Dn Alternating group An Mathieu groups M11, M12, M22, M23, M24 Conway groups Co1, Co2, Co3 Janko groups J1, J2, J3, J4 Fischer groups F22, F23, F24 Baby Monster group B Monster group M |

|

|

|

Solenoid (mathematics)

Circle group General linear group GL(n) Special linear group SL(n) Orthogonal group O(n) Special orthogonal group SO(n) Unitary group U(n) Special unitary group SU(n) Symplectic group Sp(n) Lorentz group Poincaré group Conformal group Diffeomorphism group Loop group Infinite-dimensional Lie groups O(∞) SU(∞) Sp(∞) |

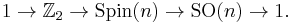

In mathematics the spin group Spin(n) [1][2] is the double cover of the special orthogonal group SO(n), such that there exists a short exact sequence of Lie groups

As a Lie group Spin(n) therefore shares its dimension, n(n − 1)/2, and its Lie algebra with the special orthogonal group. For n > 2, Spin(n) is simply connected and so coincides with the universal cover of SO(n).

The non-trivial element of the kernel is denoted  , which should not be confused with the orthogonal transform of reflection through the origin, generally denoted

, which should not be confused with the orthogonal transform of reflection through the origin, generally denoted  .

.

Spin(n) can be constructed as a subgroup of the invertible elements in the Clifford algebra Cℓ(n).

Contents |

Accidental isomorphisms

In low dimensions, there are isomorphisms among the classical Lie groups called accidental isomorphisms. For instance, there are isomorphisms between low dimensional spin groups and certain classical Lie groups, due to low dimensional isomorphisms between the root systems (and corresponding isomorphisms of Dynkin diagrams) of the different families of simple Lie algebras. Specifically, we have

- Spin(1) = O(1)

- Spin(2) = U(1) = SO(2) which acts on

by double phase rotation

by double phase rotation  →

→

- Spin(3) = Sp(1) = SU(2), corresponding to

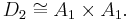

- Spin(4) = Sp(1) × Sp(1), corresponding to

- Spin(5) = Sp(2), corresponding to

- Spin(6) = SU(4), corresponding to

There are certain vestiges of these isomorphisms left over for n = 7,8 (see Spin(8) for more details). For higher n, these isomorphisms disappear entirely.

Indefinite signature

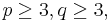

In indefinite signature, the spin group Spin(p,q) is constructed through Clifford algebras in a similar way to standard spin groups. It is a connected double cover of SO0(p,q), the connected component of the identity of the indefinite orthogonal group SO(p,q) (there are a variety of conventions on the connectedness of Spin(p,q); in this article, it is taken to be connected for p+q>2). As in definite signature, there are some accidental isomorphisms in low dimensions:

- Spin(1,1) = GL(1,R)

- Spin(2,1) = SL(2,R)

Note that Spin(p,q) = Spin(q,p).

Topological considerations

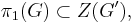

Connected and simply connected Lie groups are classified by their Lie algebra. So if G is a connected Lie group with a simple Lie algebra, with G′ the universal cover of G, there is an inclusion

with Z(G′) the centre of G′. This inclusion and the Lie algebra  of G determine G entirely (note that it is not the fact that

of G determine G entirely (note that it is not the fact that  and

and  determine G entirely; for instance SL(2,R) and PSL(2,R) have the same Lie algebra and same fundamental group

determine G entirely; for instance SL(2,R) and PSL(2,R) have the same Lie algebra and same fundamental group  , but are not isomorphic).

, but are not isomorphic).

The definite signature Spin(n) are all simply connected for (n>2), so they are the universal coverings for SO(n).

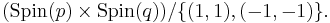

In indefinite signature, Spin(p,q) is not connected, and in general the identity component, Spin0(p,q), is not simply connected, thus it is not a universal cover. The fundamental group is most easily understood by considering the maximal compact subgroup of SO(p,q), which is SO(p)×SO(q), and noting that rather than being the product of the 2-fold covers (hence a 4-fold cover), Spin(p,q) is the "diagonal" 2-fold cover – it is a 2-fold quotient of the 4-fold cover. Explicitly, the maximal compact connected subgroup of Spin(p,q) is

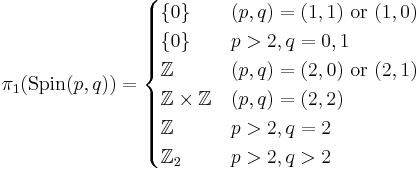

This allows us to calculate the fundamental groups of Spin(p,q), taking  :

:

Thus once  the fundamental group is

the fundamental group is  as it is a 2-fold quotient of a product of two universal covers.

as it is a 2-fold quotient of a product of two universal covers.

The maps on fundamental groups are given as follows. For  , this implies that the map

, this implies that the map  is given by

is given by  going to

going to  . For p=2, q>2, this map is given by

. For p=2, q>2, this map is given by  . And finally, for p=q=2,

. And finally, for p=q=2,  is sent to

is sent to  and

and  is sent to

is sent to  .

.

Center

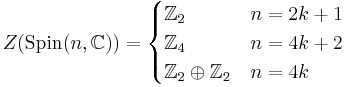

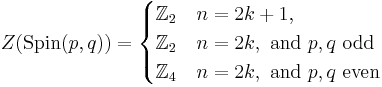

The center of the spin groups (complex and real) are given as follows:[3]

Quotient groups

Quotient groups can be obtained from a spin group by quotienting out by a subgroup of the center, with the spin group then being a covering group of the resulting quotient, and both groups having the same Lie algebra.

Quotienting out by the entire center yields the minimal such group, the projective special orthogonal group, which is centerless, while quotienting out by {±1} yields the special orthogonal group – if the center equals {±1} (namely in odd dimension), these two quotient groups agree. If the spin group is simply connected (as Spin(n) is for  ), then Spin is the maximal group in the sequence, and one has a sequence of three groups,

), then Spin is the maximal group in the sequence, and one has a sequence of three groups,

- Spin(n) → SO(n) → PSO(n),

which are the three compact real forms (or two, if SO=PSO) of the compact Lie algebra

The homotopy groups of the cover and the quotient are related by the long exact sequence of a fibration, with discrete fiber (the fiber being the kernel) – thus all homotopy groups for  are equal, but

are equal, but  and

and  may differ.

may differ.

For Spin(n) with  Spin(n) is simply connected (

Spin(n) is simply connected ( is trivial), so SO(n) is connected and has fundamental group

is trivial), so SO(n) is connected and has fundamental group  while PSO(n) is connected and has fundamental group equal to the center of Spin(n).

while PSO(n) is connected and has fundamental group equal to the center of Spin(n).

In indefinite signature the covers and homotopy groups are more complicated – Spin(p,q) is not simply connected, and quotienting also affects connected components. The analysis is simpler if one considers the maximal (connected) compact  and the component group of Spin(p,q).

and the component group of Spin(p,q).

Discrete subgroups

Discrete subgroups of the spin group can be understood by relating them to discrete subgroups of the special orthogonal group (rotational point groups).

Given the double cover  by the lattice theorem, there is a Galois connection between subgroups of Spin(n) and subgroups of SO(n) (rotational point groups): the image of a subgroup of Spin(n) is a rotational point group, and the preimage of a point group is a subgroup of Spin(n), and the closure operator on subgroups of Spin(n) is multiplication by {±1}. These may be called "binary point groups"; most familiar is the 3-dimensional case, known as binary polyhedral groups.

by the lattice theorem, there is a Galois connection between subgroups of Spin(n) and subgroups of SO(n) (rotational point groups): the image of a subgroup of Spin(n) is a rotational point group, and the preimage of a point group is a subgroup of Spin(n), and the closure operator on subgroups of Spin(n) is multiplication by {±1}. These may be called "binary point groups"; most familiar is the 3-dimensional case, known as binary polyhedral groups.

Concretely, every binary point group is either the preimage of a point group (hence denoted  for the point group

for the point group  ), or is an index 2 subgroup of the preimage of a point group which maps (isomorphically) onto the point group; in the latter case the full binary group is abstractly

), or is an index 2 subgroup of the preimage of a point group which maps (isomorphically) onto the point group; in the latter case the full binary group is abstractly  (since

(since  is central). As an example of these latter, given a cyclic group of odd order

is central). As an example of these latter, given a cyclic group of odd order  in SO(n), its preimage is a cyclic group of twice the order,

in SO(n), its preimage is a cyclic group of twice the order,  and the subgroup

and the subgroup  maps isomorphically to

maps isomorphically to

Of particular note are two series:

- higher binary tetrahedral groups, corresponding to the 2-fold cover of symmetries of the n-simplex.

- This group can also be considered as the double cover of the symmetric group,

with the alternating group being the (rotational) symmetry group of the n-simplex.

with the alternating group being the (rotational) symmetry group of the n-simplex.

- This group can also be considered as the double cover of the symmetric group,

- higher binary octahedral groups, corresponding to the 2-fold covers of the hyperoctahedral group (symmetries of the hypercube, or equivalently of its dual, the cross-polytope).

For point groups that reverse orientation, the situation is more complicated, as there are two pin groups, so there are two possible binary groups corresponding to a given point group.

See also

Related groups

- Pin group Pin(n) – two-fold cover of orthogonal group, O(n)

- Metaplectic group Mp(2n) – two-fold cover of symplectic group, Sp(2n)

References

- ^ Lawson, H. Blaine; Michelsohn, Marie-Louise (1989). Spin Geometry. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-08542-5 page 14

- ^ Friedrich, Thomas (2000), Dirac Operators in Riemannian Geometry, American Mathematical Society, ISBN 978-0-8218-2055-1 page 15

- ^ (Varadarajan 2004, p. 208)

Books

- Lawson, H. Blaine; Michelsohn, Marie-Louise (1989). Spin Geometry. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-08542-5

- Friedrich, Thomas (2000), Dirac Operators in Riemannian Geometry, American Mathematical Society, ISBN 978-0-8218-2055-1

- Varadarajan, V. S. (2004). Supersymmetry for mathematicians. AMS Bookstore. ISBN 978-0-82183574-6.