Sone

The sone was proposed as a unit of perceived loudness by Stanley Smith Stevens in 1936. In acoustics, loudness is the subjective perception of sound intensity. Although defined by Stevens as a unit, it is not one of the SI units.

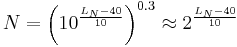

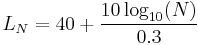

According to Stevens' definition,[1] a loudness of 1 sone is equivalent to the loudness of a signal at 40 phons, the loudness level of a 1 kHz tone at 40 dB SPL. But phons scale with level in dB, not with loudness, so the sone and phon scales are not proportional. Rather, the loudness in sones is, at least very nearly, a power law function of the signal intensity, with an exponent of 0.3.[2][3] With this exponent, each 10 phon increase (or 10 dB at 1 kHz) produces almost exactly a doubling of the loudness in sones.[4]

At frequencies other than 1 kHz, the loudness level in phons is calibrated according to the frequency response of human hearing, via a set of equal-loudness contours, and then the loudness level in phons is mapped to loudness in sones via the same power law.

The study of apparent loudness is included in the topic of psychoacoustics and employs methods of psychophysics.

Contents |

Formulas

Loudness N in sones (for LN > 40 phon):[5]

or loudness level LN in phons (for N > 1 sone):

Corrections are needed at lower levels, near the threshold of hearing.

These formulas are for single-frequency sine waves or narrowband signals. For multi-component or broadband signals, a more elaborate loudness model is required, accounting for critical bands.

To be fully precise, a measurement in sones must be specified in terms of the optional suffix G, which means that the loudness value is calculated from frequency groups, and by one of the two suffixes D (for direct field or free field) or R (for room field or diffuse field).

Examples of sound pressure, sound pressure levels, and loudness in sone

-

Source of sound sound pressure sound pressure level loudness pascal dB re 20 µPa sone threshold of pain 100 134 ~ 676 hearing damage during short-term effect 20 approx. 120 ~ 256 jet, 100 m away 6 ... 200 110 ... 140 ~ 128 ... 1024 jack hammer, 1 m away / discotheque 2 approx. 100 ~ 64 hearing damage during long-term effect 6×10−1 approx. 90 ~ 32 major road, 10 m away 2×10−1 ... 6×10−1 80 ... 90 ~ 16 ... 32 passenger car, 10 m away 2×10−2 ... 2×10−1 60 ... 80 ~ 4 ... 16 TV set at home level, 1 m away 2×10−2 ca. 60 ~ 4 normal talking, 1 m away 2×10−3 ... 2×10−2 40 ... 60 ~ 1 ... 4 very calm room 2×10−4 ... 6×10−4 20 ... 30 ~ 0.15 ... 0.4 leaves' noise, calm breathing 6×10−5 10 ~ 0.02 auditory threshold at 1 kHz 2×10−5 0 0

-

sone 1 2 4 8 16 32 64 128 256 512 1024 phon 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 110 120 130 140

See also

References

- ^ Stanley Smith Stevens: A scale for the measurement of the psychological magnitude: loudness. See: Psychological Review. 43, Nr. 5,APA Journals, 1936, pp. 405-416

- ^ Brian C. J. Moore (2007). Cochlear hearing loss: physiological, psychological and technical issues (2nd ed.). Wiley-Interscience. p. 94–95. ISBN 9780470516331. http://books.google.com/books?id=G6SbxrLVWn4C&pg=PA94.

- ^ Irving P. Herman (2007). Physics of the human body. Springer. p. 613. ISBN 9783540296034. http://books.google.com/books?id=vtubxNaSAdAC&pg=PA613.

- ^ Eberhard Hänsler, Gerhard Schmidt (2008). Speech and audio processing in adverse environments. Springer. p. 299. ISBN 9783540706014. http://books.google.com/books?id=U8cxxaVVjqYC&pg=PA299.

- ^ Hugo Fastl and Eberhard Zwicker (2007). Psychoacoustics: facts and models (3rd ed.). Springer. p. 207. ISBN 9783540231592. http://books.google.com/books?id=eGcfn9ddRhcC&pg=PA207.