Soft tissue

In anatomy, the term soft tissue refers to tissues that connect, support, or surround other structures and organs of the body, not being bone. Soft tissue includes tendons, ligaments, fascia, skin, fibrous tissues, fat, and synovial membranes (which are connective tissue), and muscles, nerves and blood vessels (which are not connective tissue).[1]

It is sometimes defined by what it is not. For example, soft tissue has been defined as "nonepithelial, extraskeletal mesenchyme exclusive of the reticuloendothelial system and glia".[2]

Contents |

Composition

The characteristic substances inside the extracellular matrix of this kind of tissue are the collagen, elastin and ground substance. Normally the soft tissue is very hydrated because of the ground substance. The fibroblasts are the most common cell responsible for the production of soft tissues' fibers and ground substance. Variations of fibroblasts, like chondroblasts, may also produce these substances.[3]

Mechanical Characteristics

At small strains, elastin confers stiffness to the tissue and stores most of the strain energy. The collagen fibers are comparatively inextensible and are usually loose (wavy,crimped). With increasing tissue deformation the collagen is gradually stretched in the direction of deformation. When taut, these fibers produce a strong growth in tissue stiffness. The composite behavior is analogous to a nylon stocking, whose rubber band does the role of elastin as the nylon does the role of collagen. In soft tissues the collagen limits the deformation and protects the tissues from injury.

Soft tissues have the potential to undergo big deformations and still come back to the initial configuration when unloaded. The stress-strain curve is nonlinear, as can be seen in Figure 1. The soft tissues are also viscoelastic, incompressible and usually anisotropic. Some viscoelastic properties observable in soft tissues are: relaxation, creep and hysteresis.[4][5]

Pseudoelasticity

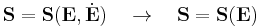

Even though soft tissues have viscoelastic properties, i.e. stress as function of strain rate, it can be approximated by a hyperelastic model after precondition to a load pattern. After some cycles of loading and unloading the material, the mechanical response becomes independent of strain rate.

Despite the independence of strain rate, preconditioned soft tissues still present hysteresis, so the mechanical response can be modeled as hyperelastic with different material constants at loading and unloading (see Figure 1). By this method the elasticity theory is used to model an inelastic material. Fung has called this model as pseudoelastic to point out that the material is not truly elastic.[5]

Residual stress

In physiological state soft tissues usually present residual stress that may be released when the tissue is excised. Physiologists and histologists must be aware of this fact to avoid mistakes when analyzing excised tissues. This retraction usually causes a visual artifact.[5]

Fung-elastic material

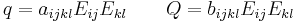

Fung developed a constitutive equation for preconditioned soft tissues which is

with

quadratic forms of Green-Lagrange strains  and

and  ,

,  and

and  material constants.[5]

material constants.[5]  is the strain energy function per volume unit, which is the mechanical strain energy for a given temperature.

is the strain energy function per volume unit, which is the mechanical strain energy for a given temperature.

Remodeling and Growth

Soft tissues have the potential to grow and remodel reacting to chemical and mechanical long term changes. The rate the fibroblasts produce tropocollagen is proportional to these stimuli. Diseases, injuries and changes in the level of mechanical load may induce remodeling. An example of this phenomenon is the thickening of farmer's hands. The remodeling of connective tissues is very know in bones by the Wolff's law (bone remodeling). Mechanobiology is the science that study the relation between stress and growth at cellular level.[4]

Growth and remodeling have a major role in the etiology of some common soft tissue diseases, like arterial stenosis and aneurisms [6][7] and any soft tissue fibrosis. Other instance of tissue remodeling, is the thickening of the cardiac muscle in response to the growth of blood pressure detected by the arterial wall.

See also

References

- ^ Definition at National Cancer Institute

- ^ Skinner, Harry B. (2006). Current diagnosis & treatment in orthopedics. Stamford, Conn: Lange Medical Books/McGraw Hill. p. 346. ISBN 0-07-143833-5.

- ^ Junqueira, L.C.U.; Carneiro, J.; Gratzl, M. (2005). Histologie. Heidelberg: Springer Medizin Verlag. p. 479. ISBN 3-540-21965-X.

- ^ a b Humphrey, Jay D. (2003). The Royal Society. ed. "Continuum biomechanics of soft biological tissues". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London A 459 (2029): 3–46. Bibcode 2003RSPSA.459....3H. doi:10.1098/rspa.2002.1060. http://rspa.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/459/2029/3.full.pdf.

- ^ a b c d Fung, Y.-C. (1993). Biomechanics: Mechanical Properties of Living Tissues. New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 568. ISBN 0387979476.

- ^ Humphrey, Jay D. (2008). Springer-Verlag. ed. "Vascular adaptation and mechanical homeostasis at tissue, cellular, and sub-cellular levels". Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics 50 (2): 53–78. doi:10.1007/s12013-007-9002-3. PMID 18209957. http://www.springerlink.com/content/j3v186330729lw80/.

- ^ Holzapfel, G.A.; Ogden, R.W. (2010). The Royal Society. ed. "Constitutive modelling of arteries". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London A 466 (2118): 1551–1597. doi:10.1098/rspa.2010.0058.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![W = \frac{1}{2}\left[q %2B c\left( e^Q -1 \right) \right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/ca69612479f068fdae4764ce42e17992.png)