Single-molecule magnet

Single-molecule magnets or SMMs are a class of metalorganic compounds, that show superparamagnetic behavior below a certain blocking temperature at the molecular scale. In this temperature range, SMMs exhibit magnetic hysteresis of purely molecular origin [1]. Contrary to conventional bulk magnets and molecule-based magnets, collective long-range magnetic ordering of magnetic moments is not necessary [1].

Contents |

Intramolecular coupling

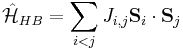

The magnetic coupling between the spins of the metal ions is mediated via superexchange interactions and can be described by the following isotropic Heisenberg Hamiltonian:

where  is the coupling constant between spin i (operator

is the coupling constant between spin i (operator  ) and spin j (operator

) and spin j (operator  ). For positive J the coupling is called ferromagnetic (parallel alignment of spins) and for negative J the coupling is called antiferromagnetic (antiparallel alignment of spins).

). For positive J the coupling is called ferromagnetic (parallel alignment of spins) and for negative J the coupling is called antiferromagnetic (antiparallel alignment of spins).

- a high spin ground state,

- a high zero-field-splitting (due to high magnetic anisotropy), and

- negligible magnetic interaction between molecules.

The combination of these properties can lead to an energy barrier so that, at low temperatures, the system can be trapped in one of the high-spin energy wells.[1]

"These molecules contain a finite number of interacting spin centers (e.g. paramagnetic ions) and thus provide ideal opportunities to study basic concepts of magnetism. Some of them possess magnetic ground states and give rise to hysteresis effects and metastable magnetic phases. They may show quantum tunneling of the magnetization which raises the question of coherent dynamics in such systems. Other types of molecules exhibit pronounced frustration effects[2], whereas so-called spin crossover substances can switch their magnetic ground state and related properties such as color under irradiation of laser light, pressure or heat. Scientists from various fields – chemistry, physics; theory and experiment – have joined the research on molecular magnetism in order to explore the unprecedented properties of these new compounds."[3]

"Single-molecule magnets (SMMs) have many important advantages over conventional nanoscale magnetic particles composed of metals, metal alloys or metal oxides. These advantages include uniform size, solubility in organic solvents, and readily alterable peripheral ligands, among others."[4]

"A single molecule magnet is an example of a macroscopic quantum system. [...] If we could detect spin flips in a single atom or molecule, we could use the spin to store information. This would enable us to increase the storage capacity of computer hard disks. [...] A good starting point for trying to detect spin flips is to find a molecule with a spin of several Bohr magnetons. [An electron has an intrinsic magnetic dipole moment of approximately one Bohr magneton.] There is a very well studied molecular magnet, Mn12-acetate, which has a spin S = 10 (Figure 3). This molecule is a disc-shaped organic molecule in which twelve Mn ions are embedded. Eight of these form a ring, each having a charge of +3 and a spin S = 2. The other four form a tetrahedron, each having a charge of +4 and a spin S = 3/2. The exchange interactions within the molecule are such that the spins of the ring align themselves in opposition to the spins of the tetrahedron, giving the molecule a total net spin S = 10."[5]

Blocking temperature

Measurements take place at very low temperatures. The so-called blocking temperature is defined as the temperature below which the relaxation of the magnetisation becomes slow compared to the time scale of a particular investigation technique.[6] A molecule magnetised at 2 K will keep 40% of its magnetisation after 2 months and by lowering the temperature to 1.5 K this will take 40 years.[6]

Future applications

As of 2008 there are many discovered types and potential uses. "Single molecule magnets (SMM) are a class of molecules exhibiting magnetic properties similar to those observed in conventional bulk magnets, but of molecular origin. SMMs have been proposed as potential candidates for several technological applications that require highly controlled thin films and patterns."[7]

"The ability of a single molecule to behave like a tiny magnet (single molecular magnets, SMMs) has seen a rapid growth in research over the last few years. SMMs represent the smallest possible magnetic devices and are a controllable, bottom-up approach to nanoscale magnetism. Potential applications of SMMs include quantum computing, high-density information storage and magnetic refrigeration."[8]

"A single molecule magnet is an example of a macroscopic quantum system. [...] If we could detect spin flips in a single atom or molecule, we could use the spin to store information. This would enable us to increase the storage capacity of computer hard disks. [...] A good starting point for trying to detect spin flips is to find a molecule with a spin of several Bohr magnetons. [An electron has an intrinsic magnetic dipole moment of approximately one Bohr magneton.] There is a very well studied molecular magnet, Mn12-acetate, which has a spin S = 10 (Figure 3). This molecule is a disc-shaped organic molecule in which twelve Mn ions are embedded. Eight of these form a ring, each having a charge of +3 and a spin S = 2. The other four form a tetrahedron, each having a charge of +4 and a spin S = 3/2. The exchange interactions within the molecule are such that the spins of the ring align themselves in opposition to the spins of the tetrahedron, giving the molecule a total net spin S = 10."[9]

Types

The archetype of single-molecule magnets is called "Mn12". It is a polymetallic manganese (Mn) complex having the formula [Mn12O12(OAc)16(H2O)4], where OAc stands for acetate. It has the remarkable property of showing an extremely slow relaxation of their magnetization below a blocking temperature.[10] [Mn12O12(OAc)16(H2O)4]·4H2O·2AcOH which is called "Mn12-acetate" is a common form of this used in research.

"Mn4" is another researched type single-molecule magnet. Three of these are:[11]

- [Mn4(hmp)6(NO3)2(MeCN)2](ClO4)2·2MeCN

- [Mn4(hmp)6(NO3)4]·(MeCN)

- [Mn4(hmp)4(acac)2(MeO)2](ClO4)2·2MeOH

In each of these Mn4 complexes "there is a planar diamond core of MnIII2MnII2 ions. An analysis of the variable-temperature and variable-field magnetization data indicate that all three molecules have intramolecular ferromagnetic coupling and a S = 9 ground state. The presence of a frequency-dependent alternating current susceptibility signal indicates a significant energy barrier between the spin-up and spin-down states for each of these three MnIII2MnII2 complexes."[11]

Single-molecule magnets are also based on iron clusters[6] because they potentially have large spin states. In addition the biomolecule ferritin is also considered a nanomagnet. In the cluster Fe8Br the cation Fe8 stands for [Fe8O2(OH)12(tacn)6]8+ with tacn representing 1,4,7-triazacyclononane.

History

Although the term "single-molecule magnet" was first employed by David Hendrickson, a chemist at the University of California, San Diego and George Christou (Indiana University) in 1996,[12] the first single-molecule magnet reported dates back to 1991.[13] The European researchers discovered that a Mn12O12(MeCO2)16(H2O)4 complex (Mn12Ac16) first synthesized in 1980[14] exhibits slow relaxation of the magnetization at low temperatures. This manganese oxide compound is composed of a central Mn(IV)4O4 cube surrounded by a ring of 8 Mn(III) units connected through bridging oxo ligands. In addition, it has 16 acetate and 4 water ligands.[15]

It was known in 2006 that the "deliberate structural distortion of a Mn6 compound via the use of a bulky salicylaldoxime derivative switches the intra-triangular magnetic exchange from antiferromagnetic to ferromagnetic resulting in an S = 12 ground state.[16]

A record magnetization was reported in 2007 for a compound related to MnAc12 ([Mn(III) 6O2(sao)6(O2CPh)2(EtOH)4]) with S = 12, D = -0.43 cm−1 and hence U = 62 cm−1 or 86 K[17] at a blocking temperature of 4.3 K. This was accomplished by replacing acetate ligands by the bulkier salicylaldoxime thus distorting the manganese ligand sphere. It is prepared by mixing the perchlorate of manganese, the sodium salt of benzoic acid, a salicylaldoxime derivate and tetramethylammonium hydroxide in water and collecting the filtrate.

Detailed behavior

Molecular magnets exhibit an increasing product (magnetic susceptibility times temperature) with decreasing temperature, and can be characterized by a shift both in position and intensity of the a.c. magnetic susceptibility.

Single-molecule magnets represent a molecular approach to nanomagnets (nanoscale magnetic particles). In addition, single-molecule magnets have provided physicists with useful test-beds for the study of quantum mechanics. Macroscopic quantum tunneling of the magnetization was first observed in Mn12O12, characterized by evenly-spaced steps in the hysteresis curve. The periodic quenching of this tunneling rate in the compound Fe8 has been observed and explained with geometric phases.

Due to the typically large, bi-stable spin anisotropy, single-molecule magnets promise the realization of perhaps the smallest practical unit for magnetic memory, and thus are possible building blocks for a quantum computer. Consequently, many groups have devoted great efforts into synthesis of additional single molecule magnets; however, the Mn12O12 complex and analogous complexes remain the canonical single molecule magnet with a 50 cm−1 spin anisotropy.

The spin anisotropy manifests itself as an energy barrier that spins must overcome when they switch from parallel alignment to antiparallel alignment. This barrier (U) is defined as:

where S is the dimensionless total spin state and D the zero-field splitting parameter (in cm−1); D can be negative but only its absolute value is considered in the equation. The barrier U is generally reported in cm−1 units or in units of Kelvin (see: electronvolt). The higher the barrier the longer a material remains magnetized and a high barrier is obtained when the molecule contains many unpaired electrons and when its zero field splitting value is large. For example, the MnAc12 cluster the spin state is 10 (involving 20 unpaired electrons) and D = -0.5 cm−1 resulting in a barrier of 50 cm−1 (equivalent to 60 K)..

The effect is also observed by hysteresis experienced when magnetization is measured in a magnetic field sweep: on lowering the magnetic field again after reaching the maximum magnetization the magnetization remains at high levels and it requires a reversed field to bring magnetization back to zero.

Recently, it has been has been reported that the energy barrier, U, is slightly dependent on Mn12 crystal size/morphology, as well as the magnetization relaxation times, which varies as function of particle size and size distributions .[18]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Introduction to Molecular Magnetism by Dr. Joris van Slageren

- ^ Frustrated Magnets, Leibniz Institute for Solid State and Materials Research, Dresden, Germany

- ^ Molecular Magnetism Web Introduction page

- ^ ScienceDaily (Mar. 27, 2000) article Several New Single-Molecule Magnets Discovered

- ^ National Physical Laboratory (UK) Home > Science + Technology > Quantum Phenomena > Nanophysics > Research – article Molecular Magnets

- ^ a b c Single-molecule magnets based on iron(III) oxo clusters Dante Gatteschi, Roberta Sessoli and Andrea Cornia Chem. Commun., 2000, 725 – 732, doi:10.1039/a908254i

- ^ Cavallini, Massimiliano; Facchini, Massimo; Albonetti, Cristiano; Biscarini, Fabio (2008). "Single molecule magnets: from thin films to nano-patterns". Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 10 (6): 784. Bibcode 2008PCCP...10..784C. doi:10.1039/b711677b. PMID 18231680.

- ^ Beautiful new single molecule magnets, 26 March 2008 – summary of the article Milios, Constantinos J.; Piligkos, Stergios; Brechin, Euan K. (2008). "Ground state spin-switching via targeted structural distortion: twisted single-molecule magnets from derivatised salicylaldoximes". Dalton Transactions (14): 1809. doi:10.1039/b716355j.

- ^ National Physical Laboratory (UK) Home > Science + Technology > Quantum Phenomena > Nanophysics > Research – article Molecular Magnets

- ^ IPCMS Liquid-crystalline Single Molecule Magnets – summary of the article Terazzi, Emmanuel; Bourgogne, Cyril; Welter, Richard; Gallani, Jean-Louis; Guillon, Daniel; Rogez, Guillaume; Donnio, Bertrand (2008). "Single-Molecule Magnets with Mesomorphic Lamellar Ordering". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47 (3): 490–495. doi:10.1002/anie.200704460.

- ^ a b Yang, E (2003). "Mn4 single-molecule magnets with a planar diamond core and S=9". Polyhedron 22 (14–17): 1857. doi:10.1016/S0277-5387(03)00173-6.

- ^ Aubin, Sheila M. J.; Wemple, Michael W.; Adams, David M.; Tsai, Hui-Lien; Christou, George; Hendrickson, David N. (1996). "Distorted MnIVMnIII3Cubane Complexes as Single-Molecule Magnets". Journal of the American Chemical Society 118 (33): 7746. doi:10.1021/ja960970f.

- ^ Caneschi, Andrea; Gatteschi, Dante; Sessoli, Roberta; Barra, Anne Laure; Brunel, Louis Claude; Guillot, Maurice (1991). "Alternating current susceptibility, high field magnetization, and millimeter band EPR evidence for a ground S = 10 state in [Mn12O12(Ch3COO)16(H2O)4].2CH3COOH.4H2O". Journal of the American Chemical Society 113 (15): 5873. doi:10.1021/ja00015a057.

- ^ Lis, T. (1980). "Preparation, structure, and magnetic properties of a dodecanuclear mixed-valence manganese carboxylate". Acta Crystallographica Section B Structural Crystallography and Crystal Chemistry 36 (9): 2042. doi:10.1107/S0567740880007893.

- ^ Chemistry of Nanostructured Materials; Yang, P., Ed.; World Scientific Publishing: Hong Kong, 2003.

- ^ Milios, Constantinos J.; Vinslava, Alina; Wood, Peter A.; Parsons, Simon; Wernsdorfer, Wolfgang; Christou, George; Perlepes, Spyros P.; Brechin, Euan K. (2007). "A Single-Molecule Magnet with a “Twist”". Journal of the American Chemical Society 129 (1): 8. doi:10.1021/ja0666755. PMID 17199262.

- ^ Milios, Constantinos J.; Vinslava, Alina; Wernsdorfer, Wolfgang; Moggach, Stephen; Parsons, Simon; Perlepes, Spyros P.; Christou, George; Brechin, Euan K. (2007). "A Record Anisotropy Barrier for a Single-Molecule Magnet". Journal of the American Chemical Society 129 (10): 2754. doi:10.1021/ja068961m. PMID 17309264.

- ^ Muntó, María; Gómez-Segura, Jordi; Campo, Javier; Nakano, Motohiro; Ventosa, Nora; Ruiz-Molina, Daniel; Veciana, Jaume (2006). "Controlled crystallization of Mn12 single-molecule magnets by compressed CO2 and its influence on the magnetization relaxation". Journal of Materials Chemistry 16 (26): 2612. doi:10.1039/b603497g.

External links

- European Institute of Molecular Magnetism EIMM

- MAGMANet (Molecular Approach to Nanomagnets and Multifunctional Materials), a Network of centres of Excellence, coordinated by the INSTM – Consorzio Interuniversitario Nazionale per la Scienza e la Tecnologia dei Materiali

- Molecular Magnetism Web, Jürgen Schnack

|

|

|||||