Single crossing condition

In economics, the single-crossing condition or single-crossing property refers to how the probability distribution of outcomes changes as a function of an input and a parameter.

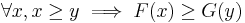

Cumulative distribution functions F and G satisfy the single-crossing condition if there exists a y such that

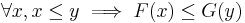

and

;

;

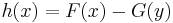

that is, function  crosses the x-axis at most once, in which case it does so from below.

crosses the x-axis at most once, in which case it does so from below.

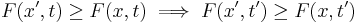

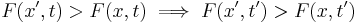

This property can be extended to two or more variables. Given x and t, for all x'>x, t'>t,

and

.

.

This condition could be interpreted as saying that for x'>x, the function g(t)=F(x',t)-F(x,t) crosses the horizontal axis at most once, and from below. The condition is not symmetric in the variables (i.e., we cannot switch x and t in the definition; the necessary inequality in the first argument is weak, while the inequality in the second argument is strict).

The single-crossing condition was posited in Samuel Karlin's 1968 monograph 'Total Positivity'[1] It was later used by Peter Diamond, Joseph Stiglitz[2], and Susan Athey[3] in studying the economics of uncertainty[4]. The single-crossing condition is also used in applications where there are a few agents or types of agents that have preferences over an ordered set. Such situations appear often in information economics, contract theory, social choice and political economics, amongst other fields.

See Also

References

- ^ Karlin, Samuel. Total positivity. Stanford Univ Pr, 1968.

- ^ Diamond, Peter A. & Stiglitz, Joseph E., 1974. "Increases in risk and in risk aversion," Journal of Economic Theory, Elsevier, vol. 8(3), pages 337-360, July.

- ^ Athey, Susan, 2001. "Single Crossing Properties and the Existence of Pure Strategy Equilibria in Games of Incomplete Information," Econometrica, Econometric Society, vol. 69(4), pages 861-89, July.

- ^ Gollier, Christian. The Economics of Risk and Time. The MIT Press, 2001, p. 103.