Sigma additivity

In mathematics, additivity and sigma additivity of a function defined on subsets of a given set are abstractions of the intuitive properties of size (length, area, volume) of a set.

Contents |

Additive (or finitely additive) set functions

Let  be a function defined on an algebra of sets

be a function defined on an algebra of sets  with values in [−∞, +∞] (see the extended real number line). The function

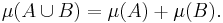

with values in [−∞, +∞] (see the extended real number line). The function  is called additive if, whenever A and B are disjoint sets in

is called additive if, whenever A and B are disjoint sets in  one has

one has

(A consequence of this is that an additive function cannot take both −∞ and +∞ as values, for the expression ∞ − ∞ is undefined.)

One can prove by mathematical induction that an additive function satisfies

for any  disjoint sets in

disjoint sets in  .

.

σ-additive set functions

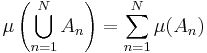

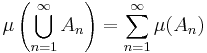

Suppose  is a σ-algebra. If for any sequence

is a σ-algebra. If for any sequence  of disjoint sets in

of disjoint sets in  one has

one has

we say that μ is countably additive or σ-additive.

Any σ-additive function is additive but not vice-versa, as shown below.

Properties

Basic properties

Useful properties of an additive function μ include the following:

- μ(∅) = 0.

- If μ is non-negative and A ⊆ B, then μ(A) ≤ μ(B).

- If A ⊆ B, then μ(B - A) = μ(B) - μ(A).

- Given A and B, μ(A ∪ B) + μ(A ∩ B) = μ(A) + μ(B).

Examples

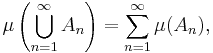

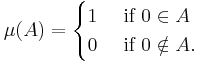

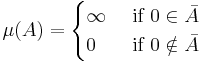

An example of a σ-additive function is the function μ defined over the power set of the real numbers, such that

If  is a sequence of disjoint sets of real numbers, then either none of the sets contains 0, or precisely one of them does. In either case the equality

is a sequence of disjoint sets of real numbers, then either none of the sets contains 0, or precisely one of them does. In either case the equality

holds.

See measure and signed measure for more examples of σ-additive functions.

An example of an additive function which is not σ-additive is obtained by considering μ, defined over the power set of the real numbers by the slightly modified formula

where the bar denotes the closure of a set.

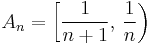

One can check that this function is additive by using the property that the closure of a finite union of sets is the union of the closures of the sets, and looking at the cases when 0 is in the closure of any of those sets or not. That this function is not σ-additive follows by considering the sequence of disjoint sets

for n=1, 2, 3, ... The union of these sets is the interval (0, 1) whose closure is [0, 1] and μ applied to the union is then infinity, while μ applied to any of the individual sets is zero, so the sum of μ(An) is also zero, which proves the counterexample.

Generalizations

One may define additive functions with values in any additive monoid (for example any group or more commonly a vector space). For sigma-additivity, one needs in addition that the concept of limit of a sequence be defined on that set. For example, spectral measures are sigma-additive functions with values in a Banach algebra. Another example, also from quantum mechanics, is the positive operator-valued measure.

See also

This article incorporates material from additive on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License.