Shulba Sutras

The Shulba Sutras or Śulbasūtras (Sanskrit śulba: "string, cord, rope") are sutra texts belonging to the Śrauta ritual and containing geometry related to fire-altar construction.

Contents |

Purpose and origins

The Shulba Sutras are part of the larger corpus of texts called the Shrauta Sutras, considered to be appendices to the Vedas. They are the only sources of knowledge of Indian mathematics from the Vedic period. Unique fire-altar shapes were associated with unique gifts from the Gods. For instance, "he who desires heaven is to construct a fire-altar in the form of a falcon"; "a fire-altar in the form of a tortoise is to be constructed by one desiring to win the world of Brahman" and "those who wish to destroy existing and future enemies should construct a fire-altar in the form of a rhombus".[1]

The four major Shulba Sutras, which are mathematically the most significant, are those composed by Baudhayana, Manava, Apastamba and Katyayana, about whom very little is known.[1] The texts are dated by comparing their grammar and vocabulary with the grammar and vocabulary of other Vedic texts.[1] The texts have been dated from around 800 BCE to 200 CE,[2] with the oldest being the sutra that was written by Baudhayana around 800 BCE to 600 BCE.[1]

There are competing theories about the origin of the geometry that is found in the Shulba sutras, and of geometry in general. According to the theory of the ritual origins of geometry, different shapes symbolized different religious ideas, and the need to manipulate these shapes lead to the creation of the pertinent mathematics. Another theory is that the mystical properties of numbers and geometry were considered spiritually powerful and consequently, led to their incorporation into religious texts.[1]

Mathematics

Pythagorean theorem

The sutras contain discussion and non-axiomatic demonstrations of cases of the Pythagorean theorem and Pythagorean triples. It is also implied and cases presented in the earlier work of Apastamba[2][3] and Baudhayana, although there is no consensus on whether or not Apastamba's rule is derived from Mesopotamia. In Baudhayana, the rules are given as follows:

1.9. The diagonal of a square produces double the area [of the square].

[...]

1.12. The areas [of the squares] produced separately by the lengths of the breadth of a rectangle together equal the area [of the square] produced by the diagonal.

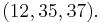

1.13. This is observed in rectangles having sides 3 and 4, 12 and 5, 15 and 8, 7 and 24, 12 and 35, 15 and 36.[4]

The Satapatha Brahmana and the Taittiriya Samhita were probably also aware of the Pythagoras theorem.[5] Seidenberg (1983) argued that either "Old Babylonia got the theorem of Pythagoras from India or that Old Babylonia and India got it from a third source".[6] Seidenberg suggested that this source might be Sumerian and may predate 1700 BC.

Pythagorean triples

Pythagorean triples are found in Apastamba's rules for altar construction.[7] They were used for the construction of right angles.[2] The complete list is:

However, since these triples are easily derived from an old Babylonian rule, Mesopotamian influence is not unlikely.[2]

Geometry

The Baudhayana Shulba sutra gives the construction of geometric shapes such as squares and rectangles.[8] It also gives, sometimes approximate, geometric area-preserving transformations from one geometric shape to another. These include transforming a square into a rectangle, an isosceles trapezium, an isosceles triangle, a rhombus, and a circle, and transforming a circle into a square.[8] In these texts approximations, such as the transformation of a circle into a square, appear side by side with more accurate statements. As an example, the statement of circling the square is given in Baudhayana as:

2.9. If it is desired to transform a square into a circle, [a cord of length] half the diagonal [of the square] is stretched from the centre to the east [a part of it lying outside the eastern side of the square]; with one-third [of the part lying outside] added to the remainder [of the half diagonal], the [required] circle is drawn.[9]

and the statement of squaring the circle is given as:

2.10. To transform a circle into a square, the diameter is divided into eight parts; one [such] part after being divided into twenty-nine parts is reduced by twenty-eight of them and further by the sixth [of the part left] less the eighth [of the sixth part].

2.11. Alternatively, divide [the diameter] into fifteen parts and reduce it by two of them; this gives the approximate side of the square [desired].[9]

The constructions in 2.9 and 2.10 give a value of π as 3.088, while the construction in 2.11 gives π as 3.004.[10]

Square roots

Altar construction also led to an estimation of the square root of 2 as found in three of the sutras. In the Baudhayana sutra it appears as:

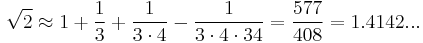

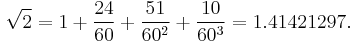

2.12. The measure is to be increased by its third and this [third] again by its own fourth less the thirty-fourth part [of that fourth]; this is [the value of] the diagonal of a square [whose side is the measure].[9]

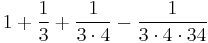

which leads to the value of the square root of two as being:

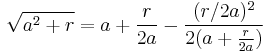

One conjecture about how such an approximation was obtained is that it was taken by the formula:

with

with  and

and  [11]

[11]

which is an approximation that follows a rule given by the twelfth century Muslim mathematician Al-Hassar.[11] The result is correct to 5 decimal places.

This formula is also similar in structure to the formula found on a Mesopotamian tablet[12] from the Old Babylonian period (1900-1600 BCE):[13]

which expresses  in the sexagesimal system, and which too is accurate up to 5 decimal places (after rounding).

in the sexagesimal system, and which too is accurate up to 5 decimal places (after rounding).

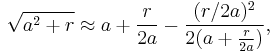

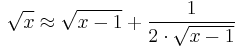

Indeed an early method for calculating square roots can be found in some Sutras, the method involves the recursive formula:  for large values of x, which bases itself on the non-recursive identity

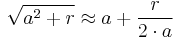

for large values of x, which bases itself on the non-recursive identity  for values of r extremely small relative to a.

for values of r extremely small relative to a.

Numerals

Before the period of the Sulbasutras was at an end, the Brahmi numerals had definitely begun to appear (c. 300BCE) and the similarity with modern day numerals is clear to see. More importantly even still was the development of the concept of decimal place value. Certain rules given by the famous Indian grammarian Pāṇini (c. 500 BCE) add a zero suffix (a suffix with no phonemes in it) to a base to form words, and this can be said somehow to imply the concept of the mathematical zero.

Incommensurables

It has sometimes been suggested the sutras contain knowledge of irrationality, but such claims are not well substantiated and unlikely to be true.[14]

List of Shulba Sutras

The following Shulba Sutras exist in print or manuscript

- Apastamba

- Baudhayana

- Manava

- Katyayana

- Maitrayaniya (somewhat similar to Manava text)

- Varaha (in manuscript)

- Vadhula (in manuscript)

- Hiranyakeshin (similar to Apastamba Shulba Sutras)

Further reading

- Parameswaran Moorthiyedath, "Sulbasutra"

- Seidenberg, A. 1983. "The Geometry of the Vedic Rituals." In The Vedic Ritual of the Fire Altar. Ed. Frits Staal. Berkeley: Asian Humanities Press.

- Sen, S.N., and A.K. Bag. 1983. The Sulbasutras. New Delhi: Indian National Science Academy.

References

- Plofker, Kim (2007). "Mathematics in India". The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A Sourcebook. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691114859.

- Boyer, Carl B. (1991). A History of Mathematics (Second Edition ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 0471543977.

- Cooke, Roger (1997). The History of Mathematics: A Brief Course. Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 0471180823.

- Cooke, Roger (2005), The History of Mathematics: A Brief Course, New York: Wiley-Interscience, 632 pages, ISBN 0471444596, http://www.amazon.com/dp/0471444596/.

Citations and footnotes

- ^ a b c d e Plofker, Kim (2007). p. 387. "Certain shapes and sizes of fire-altars were associated with particular gifts that the sacrificer desired from the gods: "he who desires heaven is to construct a fire-altar in the form of a falcon"; "a fire-altar in the form of a tortoise is to be constructed by one desiring to win the world of Brahman"; "those who wish to destroy existing and future enemies should construct a fire-altar in the form of a rhombus" [Sen and Bag 1983, 86, 98, 111].

The Sulbasutra texts are associated with the names of individual authors, about whom very little is known. Even their dates can only be roughly estimated by comparing their grammar and vocabulary with the more archaic language of earlier Vedic texts and with later works written by so-called "Classical" Sanskrit. The one we shall look at is the oldest according to these criteria, composed by one Baudhayana probably around 800-600 BCE. It tells the priests officiating at sacrifices how to construct certain shapes using stakes and marked cords. [...]

Many of the altar constructions involve area-preserving transformations, such as making a square altar into a circular or oblong rectangular one of the same size. We don't know how these geometric procedures originally came to be associated with sacrificial rituals. Various theories of the "ritual origin of geometry" infer that the geometrical figures symbolized religious ideas, and the need to manipulate them ritually inspired the development of the relevant mathematics. It seems at least equally plausible, though, that the beauty and mystery of independently discovered geometric facts were considered spirirually pwerful (perhaps like the concepts of number and divisibility mentioned about), and were incorporated into religious ritual on that account." - ^ a b c d e f g h Boyer (1991). "China and India". p. 207. "we find rules for the construction of right angles by means of triples of cords the lengths of which form Pythagorean triages, such as 3, 4, and 5, or 5, 12, and 13, or 8, 15, and 17, or 12, 35, and 37. However all of these triads are easily derived from the old Babylonian rule; hence, Mesopotamian influence in the Sulvasutras is not unlikely. Aspastamba knew that the square on the diagonal of a rectangle is equal to the sum of the squares on the two adjacent sides, but this form of the Pythagorean theorem also may have been derived from Mesopotamia. [...] So conjectural are the origin and period of the Sulbasutras that we cannot tell whether or not the rules are related to early Egyptian surveying or to the later Greek problem of altar doubling. They are variously dated within an interval of almost a thousand years stretching from the eighth century B.C. to the second century of our era."

- ^ The rule in the Apastamba cannot be derived from Old Babylon (Cf. Bryant 2001:263)

- ^ Plofker, Kim (2007). pp. 388–389.

- ^ Seidenberg 1983. Bryant 2001:262

- ^ Seidenberg 1983, 121

- ^ Joseph, G. G. 2000. The Crest of the Peacock: The Non-European Roots of Mathematics. Princeton University Press. 416 pages. ISBN 0691006598. page 229.

- ^ a b Plofker, Kim (2007). pp. 388–391.

- ^ a b c Plofker, Kim (2007). p. 391.

- ^ a b Plofker, Kim (2007). pp. 392. "The "circulature" and quadrature techniques in 2.9 and 2.10, the first of which is illustrated in figure 4.4, imply what we would call a value of π of 3.088, [...] The quadrature in 2.11, on the other hand, suggests that π = 3.004 (where s = 2r·13/15), which is already considered only "approximate." In 2.12, the ratio of a square's diagonal to its side (our

is considered to be 1 + 1/3 + 1/(3·4) - 1/(3·4·34) = 1.4142.]"

is considered to be 1 + 1/3 + 1/(3·4) - 1/(3·4·34) = 1.4142.]" - ^ a b c Cooke (1997). "The Mathematics of the Hindus". pp. 200. "The Hindus had a very good system of approximating irrational square roots. Three of the Sulva Sutras contain the approximation

for the diagonal of a square of side 1 (that is

for the diagonal of a square of side 1 (that is  ). [...] We can only conjecture how such an approximation was obtained. One guess is the approximation

). [...] We can only conjecture how such an approximation was obtained. One guess is the approximation  with a = 4/3 and r = 2/9. This approximation follows a rule given by the twelfth century Muslim mathematician Al-Hassar."

with a = 4/3 and r = 2/9. This approximation follows a rule given by the twelfth century Muslim mathematician Al-Hassar." - ^ Neugebauer, O. and A. Sachs. 1945. Mathematical Cuneiform Texts, New Haven, Connecticut, Yale University Press. p. 45.

- ^ (Cooke 2005, p. 200)

- ^ Boyer (1991). "China and India". p. 208. "It has been claimed also that the first recognition of incommensurables is to be found in India during the Sulbasutra period, but such claims are not well substantiated. The case for early Hindu awareness of incommensurable magnitudes is rendered most unlikely by the lack of evidence that Indian mathematicians of that period had come to grips with fundamental concepts."

See also

Vedic Civilization: Rigvedic period