Shannon–Hartley theorem

In information theory, the Shannon–Hartley theorem tells the maximum rate at which information can be transmitted over a communications channel of a specified bandwidth in the presence of noise. It is an application of the noisy channel coding theorem to the archetypal case of a continuous-time analog communications channel subject to Gaussian noise. The theorem establishes Shannon's channel capacity for such a communication link, a bound on the maximum amount of error-free digital data (that is, information) that can be transmitted with a specified bandwidth in the presence of the noise interference, assuming that the signal power is bounded, and that the Gaussian noise process is characterized by a known power or power spectral density. The law is named after Claude Shannon and Ralph Hartley.

Contents |

Statement of the theorem

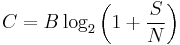

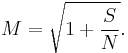

Considering all possible multi-level and multi-phase encoding techniques, the Shannon–Hartley theorem states the channel capacity C, meaning the theoretical tightest upper bound on the information rate (excluding error correcting codes) of clean (or arbitrarily low bit error rate) data that can be sent with a given average signal power S through an analog communication channel subject to additive white Gaussian noise of power N, is:

where

- C is the channel capacity in bits per second;

- B is the bandwidth of the channel in hertz (passband bandwidth in case of a modulated signal);

- S is the total received signal power over the bandwidth (in case of a modulated signal, often denoted C, i.e. modulated carrier), measured in watt or volt2;

- N is the total noise or interference power over the bandwidth, measured in watt or volt2; and

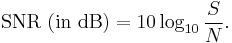

- S/N is the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) or the carrier-to-noise ratio (CNR) of the communication signal to the Gaussian noise interference expressed as a linear power ratio (not as logarithmic decibels).

Historical development

During the late 1920s, Harry Nyquist and Ralph Hartley developed a handful of fundamental ideas related to the transmission of information, particularly in the context of the telegraph as a communications system. At the time, these concepts were powerful breakthroughs individually, but they were not part of a comprehensive theory. In the 1940s, Claude Shannon developed the concept of channel capacity, based in part on the ideas of Nyquist and Hartley, and then formulated a complete theory of information and its transmission.

Nyquist rate

- Main article: Nyquist rate

In 1927, Nyquist determined that the number of independent pulses that could be put through a telegraph channel per unit time is limited to twice the bandwidth of the channel. In symbols,

where fp is the pulse frequency (in pulses per second) and B is the bandwidth (in hertz). The quantity 2B later came to be called the Nyquist rate, and transmitting at the limiting pulse rate of 2B pulses per second as signalling at the Nyquist rate. Nyquist published his results in 1928 as part of his paper "Certain topics in Telegraph Transmission Theory."

Hartley's law

During that same year, Hartley formulated a way to quantify information and its line rate (also known as data signalling rate or gross bitrate inclusive of error-correcting code 'R' across a communications channel).[1] This method, later known as Hartley's law, became an important precursor for Shannon's more sophisticated notion of channel capacity.

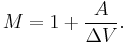

Hartley argued that the maximum number of distinct pulses that can be transmitted and received reliably over a communications channel is limited by the dynamic range of the signal amplitude and the precision with which the receiver can distinguish amplitude levels. Specifically, if the amplitude of the transmitted signal is restricted to the range of [ –A ... +A ] volts, and the precision of the receiver is ±ΔV volts, then the maximum number of distinct pulses M is given by

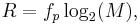

By taking information per pulse in bit/pulse to be the base-2-logarithm of the number of distinct messages M that could be sent, Hartley[2] constructed a measure of the line rate R as:

where fp is the pulse rate, also known as the symbol rate, in symbols/second or baud.

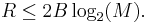

Hartley then combined the above quantification with Nyquist's observation that the number of independent pulses that could be put through a channel of bandwidth B hertz was 2B pulses per second, to arrive at his quantitative measure for achievable line rate.

Hartley's law is sometimes quoted as just a proportionality between the analog bandwidth, B, in Hertz and what today is called the digital bandwidth, R, in bit/s.[3] Other times it is quoted in this more quantitative form, as an achievable line rate of R bits per second:[4]

Hartley did not work out exactly how the number M should depend on the noise statistics of the channel, or how the communication could be made reliable even when individual symbol pulses could not be reliably distinguished to M levels; with Gaussian noise statistics, system designers had to choose a very conservative value of M to achieve a low error rate.

The concept of an error-free capacity awaited Claude Shannon, who built on Hartley's observations about a logarithmic measure of information and Nyquist's observations about the effect of bandwidth limitations.

Hartley's rate result can be viewed as the capacity of an errorless M-ary channel of 2B symbols per second. Some authors refer to it as a capacity. But such an errorless channel is an idealization, and the result is necessarily less than the Shannon capacity of the noisy channel of bandwidth B, which is the Hartley–Shannon result that followed later.

Noisy channel coding theorem and capacity

Claude Shannon's development of information theory during World War II provided the next big step in understanding how much information could be reliably communicated through noisy channels. Building on Hartley's foundation, Shannon's noisy channel coding theorem (1948) describes the maximum possible efficiency of error-correcting methods versus levels of noise interference and data corruption.[5][6] The proof of the theorem shows that a randomly constructed error correcting code is essentially as good as the best possible code; the theorem is proved through the statistics of such random codes.

Shannon's theorem shows how to compute a channel capacity from a statistical description of a channel, and establishes that given a noisy channel with capacity C and information transmitted at a line rate R, then if

there exists a coding technique which allows the probability of error at the receiver to be made arbitrarily small. This means that theoretically, it is possible to transmit information nearly without error up to nearly a limit of C bits per second.

The converse is also important. If

the probability of error at the receiver increases without bound as the rate is increased. So no useful information can be transmitted beyond the channel capacity. The theorem does not address the rare situation in which rate and capacity are equal.

Shannon–Hartley theorem

The Shannon–Hartley theorem establishes what that channel capacity is for a finite-bandwidth continuous-time channel subject to Gaussian noise. It connects Hartley's result with Shannon's channel capacity theorem in a form that is equivalent to specifying the M in Hartley's line rate formula in terms of a signal-to-noise ratio, but achieving reliability through error-correction coding rather than through reliably distinguishable pulse levels.

If there were such a thing as an infinite-bandwidth, noise-free analog channel, one could transmit unlimited amounts of error-free data over it per unit of time. Real channels, however, are subject to limitations imposed by both finite bandwidth and nonzero noise.

So how do bandwidth and noise affect the rate at which information can be transmitted over an analog channel?

Surprisingly, bandwidth limitations alone do not impose a cap on maximum information rate. This is because it is still possible for the signal to take on an indefinitely large number of different voltage levels on each symbol pulse, with each slightly different level being assigned a different meaning or bit sequence. If we combine both noise and bandwidth limitations, however, we do find there is a limit to the amount of information that can be transferred by a signal of a bounded power, even when clever multi-level encoding techniques are used.

In the channel considered by the Shannon-Hartley theorem, noise and signal are combined by addition. That is, the receiver measures a signal that is equal to the sum of the signal encoding the desired information and a continuous random variable that represents the noise. This addition creates uncertainty as to the original signal's value. If the receiver has some information about the random process that generates the noise, one can in principle recover the information in the original signal by considering all possible states of the noise process. In the case of the Shannon-Hartley theorem, the noise is assumed to be generated by a Gaussian process with a known variance. Since the variance of a Gaussian process is equivalent to its power, it is conventional to call this variance the noise power.

Such a channel is called the Additive White Gaussian Noise channel, because Gaussian noise is added to the signal; "white" means equal amounts of noise at all frequencies within the channel bandwidth. Such noise can arise both from random sources of energy and also from coding and measurement error at the sender and receiver respectively. Since sums of independent Gaussian random variables are themselves Gaussian random variables, this conveniently simplifies analysis, if one assumes that such error sources are also Gaussian and independent.

Implications of the theorem

Comparison of Shannon's capacity to Hartley's law

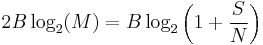

Comparing the channel capacity to the information rate from Hartley's law, we can find the effective number of distinguishable levels M:[7]

The square root effectively converts the power ratio back to a voltage ratio, so the number of levels is approximately proportional to the ratio of rms signal amplitude to noise standard deviation.

This similarity in form between Shannon's capacity and Hartley's law should not be interpreted to mean that M pulse levels can be literally sent without any confusion; more levels are needed, to allow for redundant coding and error correction, but the net data rate that can be approached with coding is equivalent to using that M in Hartley's law.

Alternative forms

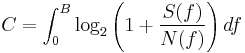

Frequency-dependent (colored noise) case

In the simple version above, the signal and noise are fully uncorrelated, in which case S + N is the total power of the received signal and noise together. A generalization of the above equation for the case where the additive noise is not white (or that the S/N is not constant with frequency over the bandwidth) is obtained by treating the channel as many narrow, independent Gaussian channels in parallel:

where

- C is the channel capacity in bits per second;

- B is the bandwidth of the channel in Hz;

- S(f) is the signal power spectrum

- N(f) is the noise power spectrum

- f is frequency in Hz.

Note: the theorem only applies to Gaussian stationary process noise. This formula's way of introducing frequency-dependent noise cannot describe all continuous-time noise processes. For example, consider a noise process consisting of adding a random wave whose amplitude is 1 or -1 at any point in time, and a channel that adds such a wave to the source signal. Such a wave's frequency components are highly dependent. Though such a noise may have a high power, it is fairly easy to transmit a continuous signal with much less power than one would need if the underlying noise was a sum of independent noises in each frequency band.

Approximations

For large or small and constant signal-to-noise ratios, the capacity formula can be approximated:

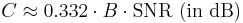

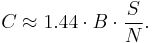

- If S/N >> 1, then

-

- where

-

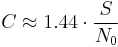

- Similarly, if S/N << 1, then

- In this low-SNR approximation, capacity is independent of bandwidth if the noise is white, of spectral density

watts per hertz, in which case the total noise power is

watts per hertz, in which case the total noise power is  .

.

Examples

- If the SNR is 20 dB, and the bandwidth available is 4 kHz, which is appropriate for telephone communications, then C = 4 log2(1 + 100) = 4 log2 (101) = 26.63 kbit/s. Note that the value of S/N = 100 is equivalent to the SNR of 20 dB.

- If the requirement is to transmit at 50 kbit/s, and a bandwidth of 1 MHz is used, then the minimum S/N required is given by 50 = 1000 log2(1+S/N) so S/N = 2C/B -1 = 0.035, corresponding to an SNR of -14.5 dB (10 x log10(0.035)).

- Let’s take the example of W-CDMA (Wideband Code Division Multiple Access), the bandwidth = 5 MHz, you want to carry 12.2 kbit/s of data (AMR voice), then the required SNR is given by 212.2/5000 -1 corresponding to an SNR of -27.7 dB for a single channel. This shows that it is possible to transmit using signals which are actually much weaker than the background noise level, as in spread-spectrum communications. However, in W-CDMA the required SNR will vary based on design calculations.

- As stated above, channel capacity is proportional to the bandwidth of the channel and to the logarithm of SNR. This means channel capacity can be increased linearly either by increasing the channel's bandwidth given a fixed SNR requirement or, with fixed bandwidth, by using higher-order modulations that need a very high SNR to operate. As the modulation rate increases, the spectral efficiency improves, but at the cost of the SNR requirement. Thus, there is an exponential rise in the SNR requirement if one adopts a 16QAM or 64QAM (see: Quadrature amplitude modulation); however, the spectral efficiency improves.

See also

Notes

- ^ R. V. L. Hartley (July 1928). "Transmission of Information" (PDF). Bell System Technical Journal. http://www.dotrose.com/etext/90_Miscellaneous/transmission_of_information_1928b.pdf.

- ^ D. A. Bell (1962). Information Theory; and its Engineering Applications (3rd ed.). New York: Pitman.

- ^ Anu A. Gokhale (2004). Introduction to Telecommunications (2nd ed.). Thomson Delmar Learning. ISBN 1401856489. http://books.google.com/?id=QowmxWAOEtYC&pg=PA37&dq=%22hartley%27s+law%22+proportional.

- ^ John Dunlop and D. Geoffrey Smith (1998). Telecommunications Engineering. CRC Press. ISBN 0748740449. http://books.google.com/?id=-kyPyn3Dst8C&pg=RA4-PA30&dq=%22hartley%27s+law%22.

- ^ C. E. Shannon (1949, reprinted 1998). The Mathematical Theory of Communication. Urbana, IL:University of Illinois Press.

- ^ C. E. Shannon (January 1949). "Communication in the presence of noise" (PDF). Proc. Institute of Radio Engineers vol. 37 (1): 10–21. http://www.stanford.edu/class/ee104/shannonpaper.pdf.

- ^ John Robinson Pierce (1980). An Introduction to Information Theory: symbols, signals & noise. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0486240614. http://books.google.com/?id=fXxde44_0zsC&pg=PP1&dq=intitle:information+intitle:theory+inauthor:pierce.

References

- Herbert Taub, Donald L. Schilling (1986). Principles of Communication Systems. McGraw-Hill.

- John M. Wozencraft and Irwin Mark Jacobs (1965). Principles of Communications Engineering. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

External links

- The relationship between information, bandwidth and noise

- On-line textbook: Information Theory, Inference, and Learning Algorithms, by David MacKay - gives an entertaining and thorough introduction to Shannon theory, including two proofs of the noisy-channel coding theorem. This text also discusses state-of-the-art methods from coding theory, such as low-density parity-check codes, and Turbo codes.

- MIT News article on Shannon Limit