SHA-1

| General | |

|---|---|

| Designers | National Security Agency |

| First published | 1993 (SHA-0), 1995 (SHA-1) |

| Series | (SHA-0), SHA-1, SHA-2, SHA-3 |

| Certification | FIPS |

| Detail | |

| Digest sizes | 160 bits |

| Structure | Merkle–Damgård construction |

| Rounds | 80 |

| Best public cryptanalysis | |

| A 2008 attack by Stéphane Manuel breaks the hash function, as it can produce hash collisions with a complexity of 251 operations.[1] | |

In cryptography, SHA-1 is a cryptographic hash function designed by the United States National Security Agency and published by the United States NIST as a U.S. Federal Information Processing Standard. SHA stands for "secure hash algorithm". The three SHA algorithms are structured differently and are distinguished as SHA-0, SHA-1, and SHA-2. SHA-1 is very similar to SHA-0, but corrects an error in the original SHA hash specification that led to significant weaknesses. The SHA-0 algorithm was not adopted by many applications. SHA-2 on the other hand significantly differs from the SHA-1 hash function.

SHA-1 is the most widely used of the existing SHA hash functions, and is employed in several widely used security applications and protocols. In 2005, security flaws were identified in SHA-1, namely that a mathematical weakness might exist, indicating that a stronger hash function would be desirable.[2] Although no successful attacks have yet been reported on the SHA-2 variants, they are algorithmically similar to SHA-1 and so efforts are underway to develop improved alternatives.[3][4] A new hash standard, SHA-3, is currently under development — an ongoing NIST hash function competition is scheduled to end with the selection of a winning function in 2012.

Contents |

The SHA-1 hash function

SHA-1 produces a 160-bit message digest based on principles similar to those used by Ronald L. Rivest of MIT in the design of the MD4 and MD5 message digest algorithms, but has a more conservative design.

The original specification of the algorithm was published in 1993 as the Secure Hash Standard, FIPS PUB 180, by US government standards agency NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology). This version is now often referred to as SHA-0. It was withdrawn by NSA shortly after publication and was superseded by the revised version, published in 1995 in FIPS PUB 180-1 and commonly referred to as SHA-1. SHA-1 differs from SHA-0 only by a single bitwise rotation in the message schedule of its compression function; this was done, according to NSA, to correct a flaw in the original algorithm which reduced its cryptographic security. However, NSA did not provide any further explanation or identify the flaw that was corrected. Weaknesses have subsequently been reported in both SHA-0 and SHA-1. SHA-1 appears to provide greater resistance to attacks, supporting the NSA’s assertion that the change increased the security.

Comparison of SHA functions

In the table below, internal state means the “internal hash sum” after each compression of a data block.

| Algorithm and variant | Output size (bits) |

Internal state size (bits) |

Block size (bits) |

Max message size (bits) |

Word size (bits) |

Rounds | Operations | Collisions found? |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHA-0 | 160 | 160 | 512 | 264 − 1 | 32 | 80 | add, and, or, xor, rotate, mod | Yes | |

| SHA-1 | Theoretical attack (251)[5] | ||||||||

| SHA-2 | SHA-256/224 | 256/224 | 256 | 512 | 264 − 1 | 32 | 64 | add, and, or, xor, shift, rotate, mod | No |

| SHA-512/384 | 512/384 | 512 | 1024 | 2128 − 1 | 64 | 80 | |||

Applications

SHA-1 forms part of several widely used security applications and protocols, including TLS and SSL, PGP, SSH, S/MIME, and IPsec. Those applications can also use MD5; both MD5 and SHA-1 are descended from MD4. SHA-1 hashing is also used in distributed revision control systems such as Git, Mercurial, and Monotone to identify revisions, and to detect data corruption or tampering. The algorithm has also been used on Nintendo's Wii gaming console for signature verification when booting, but a significant implementation flaw allows for an attacker to bypass the system's security scheme.[6]

SHA-1 and SHA-2 are the secure hash algorithms required by law for use in certain U.S. Government applications, including use within other cryptographic algorithms and protocols, for the protection of sensitive unclassified information. FIPS PUB 180-1 also encouraged adoption and use of SHA-1 by private and commercial organizations. SHA-1 is being retired for most government uses; the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology says, "Federal agencies should stop using SHA-1 for...applications that require collision resistance as soon as practical, and must use the SHA-2 family of hash functions for these applications after 2010" (emphasis in original).[7]

A prime motivation for the publication of the Secure Hash Algorithm was the Digital Signature Standard, in which it is incorporated.

The SHA hash functions have been used as the basis for the SHACAL block ciphers.

Cryptanalysis and validation

For a hash function for which L is the number of bits in the message digest, finding a message that corresponds to a given message digest can always be done using a brute force search in 2L evaluations. This is called a preimage attack and may or may not be practical depending on L and the particular computing environment. The second criterion, finding two different messages that produce the same message digest, known as a collision, requires on average only 2L/2 evaluations using a birthday attack. For the latter reason the strength of a hash function is usually compared to a symmetric cipher of half the message digest length. Thus SHA-1 was originally thought to have 80-bit strength.

Cryptographers have produced collision pairs for SHA-0 and have found algorithms that should produce SHA-1 collisions in far fewer than the originally expected 280 evaluations.

In terms of practical security, a major concern about these new attacks is that they might pave the way to more efficient ones. Whether this is the case is yet to be seen, but a migration to stronger hashes is believed to be prudent. Some of the applications that use cryptographic hashes, such as password storage, are only minimally affected by a collision attack. Constructing a password that works for a given account requires a preimage attack, as well as access to the hash of the original password, which may or may not be trivial. Reversing password encryption (e.g. to obtain a password to try against a user's account elsewhere) is not made possible by the attacks. (However, even a secure password hash can't prevent brute-force attacks on weak passwords.)

In the case of document signing, an attacker could not simply fake a signature from an existing document—the attacker would have to produce a pair of documents, one innocuous and one damaging, and get the private key holder to sign the innocuous document. There are practical circumstances in which this is possible; until the end of 2008, it was possible to create forged SSL certificates using an MD5 collision.[8]

Due to the block and iterative structure of the algorithms and the absence of additional final steps, all SHA functions are vulnerable to length-extension and partial-message collision attacks.[9] These attacks allow an attacker to forge a message, signed only by a keyed hash -  or

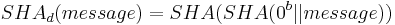

or  - by extending the message and recalculating the hash without knowing the key. The simplest improvement to prevent these attacks is to hash twice -

- by extending the message and recalculating the hash without knowing the key. The simplest improvement to prevent these attacks is to hash twice -  (

( - zero block, length is equal to block size of hash function).

- zero block, length is equal to block size of hash function).

SHA-0

At CRYPTO 98, two French researchers, Florent Chabaud and Antoine Joux, presented an attack on SHA-0 (Chabaud and Joux, 1998): collisions can be found with complexity 261, fewer than the 280 for an ideal hash function of the same size.

In 2004, Biham and Chen found near-collisions for SHA-0—two messages that hash to nearly the same value; in this case, 142 out of the 160 bits are equal. They also found full collisions of SHA-0 reduced to 62 out of its 80 rounds.

Subsequently, on 12 August 2004, a collision for the full SHA-0 algorithm was announced by Joux, Carribault, Lemuet, and Jalby. This was done by using a generalization of the Chabaud and Joux attack. Finding the collision had complexity 251 and took about 80,000 CPU hours on a supercomputer with 256 Itanium 2 processors. (Equivalent to 13 days of full-time use of the computer.)

On 17 August 2004, at the Rump Session of CRYPTO 2004, preliminary results were announced by Wang, Feng, Lai, and Yu, about an attack on MD5, SHA-0 and other hash functions. The complexity of their attack on SHA-0 is 240, significantly better than the attack by Joux et al.[10][11]

In February 2005, an attack by Xiaoyun Wang, Yiqun Lisa Yin, and Hongbo Yu was announced which could find collisions in SHA-0 in 239 operations.[12][13]

SHA-1

In light of the results for SHA-0, some experts suggested that plans for the use of SHA-1 in new cryptosystems should be reconsidered. After the CRYPTO 2004 results were published, NIST announced that they planned to phase out the use of SHA-1 by 2010 in favor of the SHA-2 variants.[14]

In early 2005, Rijmen and Oswald published an attack on a reduced version of SHA-1—53 out of 80 rounds—which finds collisions with a computational effort of fewer than 280 operations.[15]

In February 2005, an attack by Xiaoyun Wang, Yiqun Lisa Yin, and Hongbo Yu was announced.[12] The attacks can find collisions in the full version of SHA-1, requiring fewer than 269 operations. (A brute-force search would require 280 operations.)

The authors write: "In particular, our analysis is built upon the original differential attack on SHA-0 [sic], the near collision attack on SHA-0, the multiblock collision techniques, as well as the message modification techniques used in the collision search attack on MD5. Breaking SHA-1 would not be possible without these powerful analytical techniques."[16] The authors have presented a collision for 58-round SHA-1, found with 233 hash operations. The paper with the full attack description was published in August 2005 at the CRYPTO conference.

In an interview, Yin states that, "Roughly, we exploit the following two weaknesses: One is that the file preprocessing step is not complicated enough; another is that certain math operations in the first 20 rounds have unexpected security problems."[17]

On 17 August 2005, an improvement on the SHA-1 attack was announced on behalf of Xiaoyun Wang, Andrew Yao and Frances Yao at the CRYPTO 2005 rump session, lowering the complexity required for finding a collision in SHA-1 to 263.[18] On 18 December 2007 the details of this result were explained and verified by Martin Cochran.[19]

Christophe De Cannière and Christian Rechberger further improved the attack on SHA-1 in "Finding SHA-1 Characteristics: General Results and Applications,"[20] receiving the Best Paper Award at ASIACRYPT 2006. A two-block collision for 64-round SHA-1 was presented, found using unoptimized methods with 235 compression function evaluations. As this attack requires the equivalent of about 235 evaluations, it is considered to be a significant theoretical break.[21] Their attack was extended further to 73 rounds (of 80) in 2010 by Grechnikov.[22] In order to find an actual collision in the full 80 rounds of the hash function, however, massive amounts of computer time are required. To that end, a collision search for SHA-1 using the distributed computing platform BOINC began August 8, 2007, organized by the Graz University of Technology. The effort was abandoned May 12, 2009 due to lack of progress.[23]

At the Rump Session of CRYPTO 2006, Christian Rechberger and Christophe De Cannière claimed to have discovered a collision attack on SHA-1 that would allow an attacker to select at least parts of the message.[24][25]

In 2008, an attack methodology by Stéphane Manuel may produce hash collisions with an estimated theoretical complexity of 251 to 257 operations.[26]

Cameron McDonald, Philip Hawkes and Josef Pieprzyk presented a hash collision attack with claimed complexity 252 at the Rump session of Eurocrypt 2009.[27] However, the accompanying paper, "Differential Path for SHA-1 with complexity O(252)" has been withdrawn due to the authors' discovery that their estimate was incorrect.[28]

Marc Stevens runs a project called HashClash[29], implementing a differential path attack against SHA-1. On 8 November 2010, he claimed he had a fully working near-collision attack against full SHA-1 working with an estimated complexity equivalent to 257.5 SHA-1 compressions.

Official validation

Implementations of all FIPS-approved security functions can be officially validated through the CMVP program, jointly run by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the Communications Security Establishment (CSE). For informal verification, a package to generate a high number of test vectors is made available for download on the NIST site; the resulting verification however does not replace, in any way, the formal CMVP validation, which is required by law for certain applications.

As of February 2011[update], there are nearly 1400 validated implementations of SHA-1, with around a dozen of them capable of handling messages with a length in bits not a multiple of eight (see SHS Validation List).

Examples and pseudocode

Example hashes

These are examples of SHA-1 digests. ASCII encoding is used for all messages.

SHA1("The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog")

= 2fd4e1c6 7a2d28fc ed849ee1 bb76e739 1b93eb12

Even a small change in the message will, with overwhelming probability, result in a completely different hash due to the avalanche effect. For example, changing dog to cog produces a hash with different values for 81 of the 160 bits:

SHA1("The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy cog")

= de9f2c7f d25e1b3a fad3e85a 0bd17d9b 100db4b3

The hash of the zero-length string is:

SHA1("")

= da39a3ee 5e6b4b0d 3255bfef 95601890 afd80709

SHA-1 pseudocode

Pseudocode for the SHA-1 algorithm follows:

Note 1: All variables are unsigned 32 bits and wrap modulo 232 when calculating Note 2: All constants in this pseudo code are in big endian. Within each word, the most significant byte is stored in the leftmost byte position Initialize variables: h0 = 0x67452301 h1 = 0xEFCDAB89 h2 = 0x98BADCFE h3 = 0x10325476 h4 = 0xC3D2E1F0 Pre-processing: append the bit '1' to the message append 0 ≤ k < 512 bits '0', so that the resulting message length (in bits) is congruent to 448 (mod 512) append length of message (before pre-processing), in bits, as 64-bit big-endian integer Process the message in successive 512-bit chunks: break message into 512-bit chunks for each chunk break chunk into sixteen 32-bit big-endian words w[i], 0 ≤ i ≤ 15 Extend the sixteen 32-bit words into eighty 32-bit words: for i from 16 to 79 w[i] = (w[i-3] xor w[i-8] xor w[i-14] xor w[i-16]) leftrotate 1 Initialize hash value for this chunk: a = h0 b = h1 c = h2 d = h3 e = h4 Main loop:[30] for i from 0 to 79 if 0 ≤ i ≤ 19 then f = (b and c) or ((not b) and d) k = 0x5A827999 else if 20 ≤ i ≤ 39 f = b xor c xor d k = 0x6ED9EBA1 else if 40 ≤ i ≤ 59 f = (b and c) or (b and d) or (c and d) k = 0x8F1BBCDC else if 60 ≤ i ≤ 79 f = b xor c xor d k = 0xCA62C1D6 temp = (a leftrotate 5) + f + e + k + w[i] e = d d = c c = b leftrotate 30 b = a a = temp Add this chunk's hash to result so far: h0 = h0 + a h1 = h1 + b h2 = h2 + c h3 = h3 + d h4 = h4 + e Produce the final hash value (big-endian): digest = hash = h0 append h1 append h2 append h3 append h4

The constant values used are chosen as nothing up my sleeve numbers: the four round constants k are 230 times the square roots of 2, 3, 5 and 10. The first four starting values for h0 through h3 are the same as the MD5 algorithm, and the fifth (for h4) is similar.

Instead of the formulation from the original FIPS PUB 180-1 shown, the following equivalent expressions may be used to compute f in the main loop above:

(0 ≤ i ≤ 19): f = d xor (b and (c xor d)) (alternative 1) (0 ≤ i ≤ 19): f = (b and c) xor ((not b) and d) (alternative 2) (0 ≤ i ≤ 19): f = (b and c) + ((not b) and d) (alternative 3) (0 ≤ i ≤ 19): f = vec_sel(d, c, b) (alternative 4) (40 ≤ i ≤ 59): f = (b and c) or (d and (b or c)) (alternative 1) (40 ≤ i ≤ 59): f = (b and c) or (d and (b xor c)) (alternative 2) (40 ≤ i ≤ 59): f = (b and c) + (d and (b xor c)) (alternative 3) (40 ≤ i ≤ 59): f = (b and c) xor (b and d) xor (c and d) (alternative 4)

Max Locktyukhin has also shown[31] that for the rounds 32–79 the computation of:

w[i] = (w[i-3] xor w[i-8] xor w[i-14] xor w[i-16]) leftrotate 1

can be replaced with:

w[i] = (w[i-6] xor w[i-16] xor w[i-28] xor w[i-32]) leftrotate 2

This transformation keeps all operands 64-bit aligned and, by removing the dependency of w[i] on w[i-3], allows efficient SIMD implementation with a vector length of 4 such as x86 SSE instructions.

See also

- Comparison of cryptographic hash functions

- Digital timestamping

- Hash collision

- Hashcash

- International Association for Cryptologic Research (IACR)

- RIPEMD-160

- Secure Hash Standard

- sha1sum

- Tiger

- Whirlpool

References

- ^ Stéphane Manuel. Classification and Generation of Disturbance Vectors for Collision Attacks against SHA-1. http://eprint.iacr.org/2008/469.pdf.

- ^ Schneier on Security: Cryptanalysis of SHA-1

- ^ Schneier on Security: NIST Hash Workshop Liveblogging (5)

- ^ Hash cracked – heise Security

- ^ Classification and Generation of Disturbance Vectors for Collision Attacks against SHA-1

- ^ http://debugmo.de/?p=61 Debugmo.de "For verifiying the hash (which is the only thing they verify in the signature), they have chosen to use a function (strncmp) which stops on the first nullbyte – with a positive result. Out of the 160 bits of the SHA1-hash, up to 152 bits are thrown away."

- ^ National Institute on Standards and Technology Computer Security Resource Center, NIST's Policy on Hash Functions, accessed March 29, 2009.

- ^ Alexander Sotirov, Marc Stevens, Jacob Appelbaum, Arjen Lenstra, David Molnar, Dag Arne Osvik, Benne de Weger, MD5 considered harmful today: Creating a rogue CA certificate, accessed March 29, 2009

- ^ Niels Ferguson, Bruce Schneier, and Tadayoshi Kohno, Cryptography Engineering, John Wiley & Sons, 2010. ISBN 978-0-470-47424-2

- ^ Freedom to Tinker » Blog Archive » Report from Crypto 2004

- ^ Google.com

- ^ a b Schneier on Security: SHA-1 Broken

- ^ (Chinese) Sdu.edu.cn, Shandong University

- ^ National Institute of Standards and Technology

- ^ Cryptology ePrint Archive

- ^ MIT.edu, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- ^ Fixing a hole in security | Tech News on ZDNet

- ^ Schneier on Security: New Cryptanalytic Results Against SHA-1

- ^ Notes on the Wang et al. $2^{63}$ SHA-1 Differential Path

- ^ Christophe De Cannière, Christian Rechberger (2006-11-15). Finding SHA-1 Characteristics: General Results and Applications. http://www.springerlink.com/content/q42205u702p5604u/.

- ^ "IAIK Krypto Group – Description of SHA-1 Collision Search Project". http://www.iaik.tugraz.at/content/research/krypto/sha1/SHA1Collision_Description.php. Retrieved 2009-06-30.

- ^ "Collisions for 72-step and 73-step SHA-1: Improvements in the Method of Characteristics". http://eprint.iacr.org/2010/413. Retrieved 2010-07-24.

- ^ "SHA-1 Collision Search Graz". http://boinc.iaik.tugraz.at/sha1_coll_search/. Retrieved 2009-06-30.

- ^ SHA-1 hash function under pressure – heise Security

- ^ Crypto 2006 Rump Schedule

- ^ Stéphane Manuel. Classification and Generation of Disturbance Vectors for Collision Attacks against SHA-1. http://eprint.iacr.org/2008/469.pdf. Retrieved 2011-05-19.

- ^ SHA-1 collisions now 2^52

- ^ International Association for Cryptologic Research

- ^ HashClash - Framework for MD5 & SHA-1 Differential Path Construction and Chosen-Prefix Collisions for MD5

- ^ http://www.faqs.org/rfcs/rfc3174.html

- ^ Locktyukhin, Max; Farrel, Kathy (2010-03-31), "Improving the Performance of the Secure Hash Algorithm (SHA-1)", Intel Software Knowledge Base (Intel), http://software.intel.com/en-us/articles/improving-the-performance-of-the-secure-hash-algorithm-1/, retrieved 2010-04-02

- Florent Chabaud, Antoine Joux: Differential Collisions in SHA-0. CRYPTO 1998. pp56–71

- Eli Biham, Rafi Chen, Near-Collisions of SHA-0, Cryptology ePrint Archive, Report 2004/146, 2004 (appeared on CRYPTO 2004), IACR.org

- Xiaoyun Wang, Hongbo Yu and Yiqun Lisa Yin, Efficient Collision Search Attacks on SHA-0, CRYPTO 2005, CMU.edu

- Xiaoyun Wang, Yiqun Lisa Yin and Hongbo Yu, Finding Collisions in the Full SHA-1, Crypto 2005 MIT.edu

- Henri Gilbert, Helena Handschuh: Security Analysis of SHA-256 and Sisters. Selected Areas in Cryptography 2003: pp175–193

- http://www.unixwiz.net/techtips/iguide-crypto-hashes.html

- "Proposed Revision of Federal Information Processing Standard (FIPS) 180, Secure Hash Standard". Federal Register 59 (131): 35317–35318. 1994-07-11. http://frwebgate1.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/waisgate.cgi?WAISdocID=5963452267+0+0+0&WAISaction=retrieve. Retrieved 2007-04-26.

External links

Standards: SHA-1, SHA-2

- CSRC Cryptographic Toolkit – Official NIST site for the Secure Hash Standard

- FIPS 180-2: Secure Hash Standard (SHS) (PDF, 236 kB) – Current version of the Secure Hash Standard (SHA-1, SHA-224, SHA-256, SHA-384, and SHA-512), 1 August 2002, amended 25 February 2004

- RFC 3174 (with sample C implementation)

Cryptanalysis

- Interview with Yiqun Lisa Yin concerning the attack on SHA-1

- Lenstra's Summary of impact of the February 2005 cryptanalytic results

- Explanation of the successful attacks on SHA-1 (3 pages, 2006)

- Cryptography Research – Hash Collision Q&A

- Online SHA1 hash crack using Rainbow tables

- Hash Project Web Site: software- and hardware-based cryptanalysis of SHA-1

- HashClash - Framework for MD5 & SHA-1 Differential Path Construction and Chosen-Prefix Collisions for MD5

Implementations

- Libgcrypt

- A general purpose cryptographic library based on the code from GNU Privacy Guard.

- OpenSSL

- The widely used OpenSSL

cryptolibrary includes free, open-source – implementations of SHA-1, SHA-224, SHA-256, SHA-384, and SHA-512 - cryptlib

- an open source cross-platform software security toolkit library

- Crypto++

- A public domain C++ class library of cryptographic schemes, including implementations of the SHA-1, SHA-224, SHA-256, SHA-384, and SHA-512 algorithms.

- Bouncy Castle

- The Bouncy Castle Library is a free Java and C# class library that contains implementations of the SHA-1, SHA-224, SHA-256, SHA-384 and SHA-512 algorithms as well as other algorithms like Whirlpool, Tiger, RIPEMD, GOST-3411, MD2, MD4 and MD5.

- jsSHA

- A cross-browser JavaScript library for client-side calculation of SHA digests, despite the fact that JavaScript does not natively support the 64-bit operations required for SHA-384 and SHA-512.

- LibTomCrypt

- A portable ISO C cryptographic toolkit, Public Domain.

- Intel

- Fast implementation of SHA-1 using Intel Supplemental SSE3 extensions, free for commercial or non-commercial use.

- md5deep

- A set of programs to compute MD5, SHA-1, SHA-256, Tiger, or Whirlpool cryptographic message digests on an arbitrary number of files. It is used in computer security, system administration and computer forensics communities for purposes of running large numbers of files through any of several different cryptographic digests. It is similar to the md5sum.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||