Seifert surface

In mathematics, a Seifert surface (named after German mathematician Herbert Seifert[1][2]) is a surface whose boundary is a given knot or link.

Such surfaces can be used to study the properties of the associated knot or link. For example, many knot invariants are most easily calculated using a Seifert surface. Seifert surfaces are also interesting in their own right, and the subject of considerable research.

Specifically, let L be a tame oriented knot or link in Euclidean 3-space (or in the 3-sphere). A Seifert surface is a compact, connected, oriented surface S embedded in 3-space whose boundary is L such that the orientation on L is just the induced orientation from S, and every connected component of S has non-empty boundary.

Note that any compact, connected, oriented surface with nonempty boundary in Euclidean 3-space is the Seifert surface associated to its boundary link. A single knot or link can have many different inequivalent Seifert surfaces. A Seifert surface must be oriented. It is possible to associate unoriented (and not necessarily orientable) surfaces to knots as well.

Contents |

Examples

The standard Möbius strip has the unknot for a boundary but is not considered to be a Seifert surface for the unknot because it is not orientable.

The "checkerboard" coloring of the usual minimal crossing projection of the trefoil knot gives a Mobius strip with three half twists. As with the previous example, this is not a Seifert surface as it is not orientable. Applying Seifert's algorithm to this diagram, as expected, does produce a Seifert surface; in this case, it is a punctured torus of genus g=1, and the Seifert matrix is

Existence and Seifert matrix

It is a theorem that any link always has an associated Seifert surface. This theorem was first published by Frankl and Pontrjagin in 1930.[3] A different proof was published in 1934 by Herbert Seifert and relies on what is now called the Seifert algorithm. The algorithm produces a Seifert surface  , given a projection of the knot or link in question.

, given a projection of the knot or link in question.

Suppose that link has m components (m=1 for a knot), the diagram has d crossing points, and resolving the crossings (preserving the orientation of the knot) yields f circles. Then the surface  is constructed from f disjoint disks by attaching d bands. The homology group

is constructed from f disjoint disks by attaching d bands. The homology group  is free abelian on 2g generators, where

is free abelian on 2g generators, where

- g = (2 + d − f − m)/2

is the genus of  . The intersection form Q on

. The intersection form Q on  is skew-symmetric, and there is a basis of 2g cycles

is skew-symmetric, and there is a basis of 2g cycles

- a1,a2,...,a2g

with

- Q=(Q(ai,aj))

the direct sum of g copies of

.

.

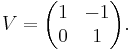

The 2g 2g integer Seifert matrix

2g integer Seifert matrix

- V=(v(i,j)) has

the linking number in Euclidean 3-space (or in the 3-sphere) of ai and the pushoff of aj out of the surface, with

the linking number in Euclidean 3-space (or in the 3-sphere) of ai and the pushoff of aj out of the surface, with

*

*

where V*=(v(j,i)) the transpose matrix. Every integer 2g 2g matrix

2g matrix  with

with  *

* arises as the Seifert matrix of a knot with genus g Seifert surface.

arises as the Seifert matrix of a knot with genus g Seifert surface.

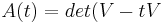

The Alexander polynomial is computed from the Seifert matrix by  *), which is a polynomial in the indeterminate

*), which is a polynomial in the indeterminate  of degree

of degree  . The Alexander polynomial is independent of the choice of Seifert surface

. The Alexander polynomial is independent of the choice of Seifert surface  , and is an invariant of the knot or link.

, and is an invariant of the knot or link.

The signature of a knot is the signature of the symmetric Seifert matrix  . It is again an invariant of the knot or link.

. It is again an invariant of the knot or link.

Genus of a knot

Seifert surfaces are not at all unique: a Seifert surface S of genus g and Seifert matrix V can be modified by a surgery, to be replaced by a Seifert surface S' of genus g+1 and Seifert matrix

- V'=V

.

.

The genus of a knot K is the knot invariant defined by the minimal genus g of a Seifert surface for K.

For instance:

- An unknot—which is, by definition, the boundary of a disc—has genus zero. Moreover, the unknot is the only knot with genus zero.

- The trefoil knot has genus one, as does the figure-eight knot.

- The genus of a (p,q)-torus knot is (p − 1)(q − 1)/2

- The degree of the Alexander polynomial is a lower bound on twice the genus of the knot.

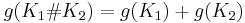

A fundamental property of the genus is that it is additive with respect to the knot sum:

See also

References

- ^ Seifert, H. (1934). "Über das Geschlecht von Knoten". Math. Annalen 110 (1): 571–592. doi:10.1007/BF01448044. (German)

- ^ van Wijk, Jarke J.; Cohen, Arjeh M. (2006). "Visualization of Seifert Surfaces". IEEE Trans. on Visualization and Computer Graphics 12 (4): 485–496. doi:10.1109/TVCG.2006.83.

- ^ Frankl, F.; Pontrjagin, L. (1930). "Ein Knotensatz mit Anwendung auf die Dimensionstheorie". Math. Annalen 102 (1): 785–789. doi:10.1007/BF01782377. (German)

External links

- The SeifertView programme of Jack van Wijk visualizes the Seifert surfaces of knots constructed using Seifert's algorithm.