Seiche

- "Seiche" is also a French term for a cuttlefish or Bobtail squid.

A seiche ( /ˈseɪʃ/ saysh) is a standing wave in an enclosed or partially enclosed body of water. Seiches and seiche-related phenomena have been observed on lakes, reservoirs, swimming pools, bays, harbors and seas. The key requirement for formation of a seiche is that the body of water be at least partially bounded, allowing the formation of the standing wave.

The term was promoted by the Swiss hydrologist François-Alphonse Forel in 1890, who was the first to make scientific observations of the effect in Lake Geneva, Switzerland.[1] The word originates in a Swiss French dialect word that means "to sway back and forth", which had apparently long been used in the region to describe oscillations in alpine lakes.

Contents |

Causes and nature of seiches

Seiches are often imperceptible to the naked eye, and observers in boats on the surface may not notice that a seiche is occurring due to the extremely long wavelengths. The effect is caused by resonances in a body of water that has been disturbed by one or more of a number of factors, most often meteorological effects (wind and atmospheric pressure variations), seismic activity or by tsunamis.[2] Gravity always seeks to restore the horizontal surface of a body of liquid water, as this represents the configuration in which the water is in hydrostatic equilibrium. Vertical harmonic motion results, producing an impulse that travels the length of the basin at a velocity that depends on the depth of the water. The impulse is reflected back from the end of the basin, generating interference. Repeated reflections produce standing waves with one or more nodes, or points, that experience no vertical motion. The frequency of the oscillation is determined by the size of the basin, its depth and contours, and the water temperature.

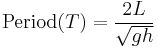

The longest natural period[3] for a seiche in an enclosed rectangular body of water is usually represented by the Merian formula:

where L is the length, h the average depth of the body of water, and g the acceleration of gravity.[4]

Higher order harmonics are also observed. The period of the second harmonic will be half the natural period, the period of the third harmonic will be a third of the natural period, and so forth.

Seiches around the world

Seiches have been observed on both lakes and seas. The key requirement is that the body of water be partially constrained to allow formation of standing waves. Regularity of geometry is not required, even harbors with exceedingly irregular shapes are routinely observed to oscillate with very stable frequencies.

Lake seiches

Small rhythmic seiches are almost always present on larger lakes. On the North American Great Lakes, seiche is often called slosh. It is always present, but is usually unnoticeable, except during periods of unusual calm. Harbours, bays, and estuaries are often prone to small seiches with amplitudes of a few centimeters and periods of a few minutes. Seiches can also form in semi-enclosed seas; the North Sea often experiences a lengthwise seiche with a period of about 36 hours.

The National Weather Service issues low water advisories for portions of the Great Lakes when seiches of 2 feet or greater are likely to occur.[5] Lake Erie is particularly prone to wind-caused seiches because of its shallowness and elongation. These can lead to extreme seiches of up to 5 m (16 feet) between the ends of the lake. The effect is similar to a storm surge like that caused by hurricanes along ocean coasts, but the seiche effect can cause oscillation back and forth across the lake for some time. In 1954, Hurricane Hazel piled up water along the northwestern Lake Ontario shoreline near Toronto, causing extensive flooding, and established a seiche that subsequently caused flooding along the south shore.

Lake seiches can occur very quickly: on July 13, 1995, a big seiche on Lake Superior caused the water level to fall and then rise again by three feet (one meter) within fifteen minutes, leaving some boats hanging from the docks on their mooring lines when the water retreated.[6] The same storm system that caused the 1995 seiche on Lake Superior produced a similar effect in Lake Huron, in which the water level at Port Huron changed by six feet (1.8 m) over two hours.[7] On Lake Michigan, eight fishermen were swept away and drowned when a 10-foot seiche hit the Chicago waterfront on June 26, 1954.[8]

Lakes in seismically active areas, such as Lake Tahoe in California/Nevada, are significantly at risk from seiches. Geological evidence indicates that the shores of Lake Tahoe may have been hit by seiches and tsunamis as much as 10 m (33 feet) high in prehistoric times, and local researchers have called for the risk to be factored into emergency plans for the region.[9]

Earthquake-generated seiches can be observed thousands of miles away from the epicentre of a quake. Swimming pools are especially prone to seiches caused by earthquakes, as the ground tremors often match the resonant frequencies of small bodies of water. The 1994 Northridge earthquake in California caused swimming pools to overflow across southern California. The massive Good Friday Earthquake that hit Alaska in 1964 caused seiches in swimming pools as far away as Puerto Rico. The earthquake that hit Lisbon, Portugal in 1755 caused seiches 2,000 miles (3,000 km) away in Loch Lomond, Loch Long, Loch Katrine and Loch Ness in Scotland [1] and in canals in Sweden. The 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake caused seiches in standing water bodies in many Indian states as well as in Bangladesh, Nepal and northern Thailand.[10] Seiches were again observed in Uttar Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and West Bengal in India as well as in many locations in Bangladesh during the 2005 Kashmir earthquake.[11] The 1950 Chayu-Upper Assam earthquake is known to have generated seiches as far as Norway and southern England. Other earthquakes in the Indian sub-continent known to have generated seiches include the 1803 Kumaon-Barahat, 1819 Allah Bund, 1842 Central Bengal, 1905 Kangra, 1930 Dhubri, 1934 Nepal-Bihar, 2001 Bhuj, 2005 Nias, 2005 Teresa Island earthquakes. The February 27, 2010 Chile earthquake produced a seiche on Lake Pontchartrain, Louisiana with a height of around 0.5 feet. Seiches up to at least 1.8 m (6 feet) were observed in Sognefjorden, Norway during the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake.[12]

Sea and bay seiches

Seiches have been observed in seas such as the Adriatic Sea and the Baltic Sea, resulting in flooding of Venice and St. Petersburg respectively. The latter is constructed on drained marshlands at the mouth of the Neva river. Seiche-induced flooding is common along the Neva river in the autumn. The seiche is driven by a low pressure region in the North Atlantic moving onshore, giving rise to cyclonic lows on the Baltic Sea. The low pressure of the cyclone draws greater-than-normal quantities of water into the virtually land-locked Baltic. As the cyclone continues inland, long, low-frequency seiche waves with wavelengths up to several hundred kilometers are established in the Baltic. When the waves reach the narrow and shallow Neva Bay, they become much higher — ultimately flooding the Neva embankments.[13] Similar phenomena are observed at Venice, resulting in the MOSE Project, a system of 79 mobile barriers designed to protect the three entrances to the Venetian Lagoon.

Nagasaki Bay is a typical area in Japan where seiches have been observed from time to time, most often in the spring — especially in March. On 31 March 1979, the Nagasaki tide station recorded a maximum water-level displacement of 2.78 metres (9.1 ft), at that location and due to the seiche. The maximum water-level displacement in the whole bay during this seiche event is assumed to have reached 4.70 metres (15.4 ft), at the bottom of the bay. Seiches in Western Kyushu — including Nagasaki Bay — are often induced by a low in the atmospheric pressure passing South of Kyushu island.[14] Seiches in Nagasaki Bay have a period of about 30 to 40 minutes. Locally, seiche is called Abiki. The word of Abiki is considered to have been derived from Amibiki, which literally means: the dragging-away (biki) of a fishing net (ami). Seiches not only cause damage to the local fishery but also may result in flooding of the coast around the bay, as well as in the destruction of port facilities.

Seiches can also be induced by tsunami, a wave train (series of waves) generated in a body of water by a pulsating or abrupt disturbance that vertically displaces the water column. On occasion, tsunamis can produce seiches as a result of local geographic peculiarities. For instance, the tsunami that hit Hawaii in 1946 had a fifteen-minute interval between wave fronts. The natural resonant period of Hilo Bay is about thirty minutes. That meant that every second wave was in phase with the motion of Hilo Bay, creating a seiche in the bay. As a result, Hilo suffered worse damage than any other place in Hawaii, with the tsunami/seiche reaching a height of 26 feet along the Hilo Bayfront, killing 96 people in the city alone. Seiche waves may continue for several days after a tsunami.

Underwater (internal) waves

Although the bulk of the technical literature addresses surface seiches, which are readily observed, seiches are also observed beneath the lake surface acting along the thermocline[15] in constrained bodies of water.

Engineering for seiche protection

Engineers consider seiche phenomena in the design of flood protection works (e.g., Saint Petersburg Dam), reservoirs and dams (e.g., Grand Coulee Dam), potable water storage basins, harbours and even spent nuclear fuel storage basins.

See also

- Clapotis

- Earthquake engineering

- Severe weather terminology (United States)

- Severe weather terminology (Canada)

- Tsunami hazard in lakes

- Vajont Dam

Notes

- ^ Darwin, G. H. (1898). The Tides and Kindred Phenomena in the Solar System. London: John Murray.. See pp. 21–31.

- ^ Tsunamis are normally associated with earthquakes, but landslides, volcanic eruptions and meteorite impacts all have the potential to generate a tsunami.

- ^ The longest natural period is the period associated with the fundamental resonance for the body of water—corresponding to the longest standing wave.

- ^ As an example, the period for a seiche wave in a body of water 10 meters deep and 5 kilometers long would be 1000 seconds or about 17 minutes, while a body about 300 km long (such as the Gulf of Finland) and somewhat deeper has a period closer to 12 hours.

- ^ National Weather Service. National Weather Service Instruction 10-301. Retrieved on 2008-01-31.

- ^ Ben Korgen. Bonanza for Lake Superior: Seiches Do More Than Move Water. Retrieved on 2008-01-31

- ^ "Lake Huron Storm Surge July 13, 1995". NOAA. http://www.glerl.noaa.gov/seagrant/glwlphotos/Seiche/13July1995/13July1995Storm.html. Retrieved 2009-03-13.

- ^ Illinois State Geological Survey. Seiches: Sudden, Large Waves a Lake Michigan Danger. Retrieved on 2008-01-31.

- ^ Kathryn Brown. Tsunami! At Lake Tahoe? Retrieved on 2008-01-31.

- ^ In fact, one person was drowned after being swept away in a particularly energetic seiches in the Jalangi River in the Nadia district to the north of Kolkata in West Bengal (see also Sumatra-Andaman Earthquake)

- ^ Kashmir earthquake

- ^ Fjorden svinga av skjelvet Retrieved on 2011-03-17.

- ^ This behaves in a fashion similar to a tidal bore where incoming tides are funneled into a shallow, narrowing river via a broad bay. The funnel-like shape increases the height of the tide above normal, and the flood appears as a relatively rapid increase in the water level.

- ^ Hibiya, Toshiyuki; Kinjiro Kajiura (1982). "Origin of the Abiki Phenomenon (a kind of Seiche) in Nagasaki Bay" (PDF). Journal of Oceanographical Society of Japan 38 (3): 172–182. doi:10.1007/BF02110288. http://www.terrapub.co.jp/journals/JO/JOSJ/pdf/3803/38030172.pdf. Retrieved 2009-02-26.

- ^ The thermocline is the boundary between colder lower layer (hypolimnion) and warmer upper layer (epilimnion).

Further reading

- Jackson, J. R. (1833). "On the Seiches of Lakes". Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London 3: 271–275. doi:10.2307/1797612.

External links

General

- What is a seiche?

- Seiche. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved January 24, 2004, from Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service.

- Seiche calculator

- Bonanza for Lake Superior: Seiches Do More Than Move Water

- Great Lakes Storms Photo Gallery Seiches, Storm Surges, and Edge Waves from NOAA

Relationship to aquatic "monsters"