Scattering parameters

Scattering parameters or S-parameters (the elements of a scattering matrix or S-matrix) describe the electrical behavior of linear electrical networks when undergoing various steady state stimuli by electrical signals.

The parameters are useful for electrical engineering, electronics engineering, and communication systems design, and especially for microwave engineering.

The S-parameters are members of a family of similar parameters, other examples being: Y-parameters,[1] Z-parameters,[2] H-parameters, T-parameters or ABCD-parameters.[3][4] They differ from these, in the sense that S-parameters do not use open or short circuit conditions to characterize a linear electrical network; instead, matched loads are used. These terminations are much easier to use at high signal frequencies than open-circuit and short-circuit terminations. Moreover, the quantities are measured in terms of power.

Many electrical properties of networks of components (inductors, capacitors, resistors) may be expressed using S-parameters, such as gain, return loss, voltage standing wave ratio (VSWR), reflection coefficient and amplifier stability. The term 'scattering' is more common to optical engineering than RF engineering, referring to the effect observed when a plane electromagnetic wave is incident on an obstruction or passes across dissimilar dielectric media. In the context of S-parameters, scattering refers to the way in which the traveling currents and voltages in a transmission line are affected when they meet a discontinuity caused by the insertion of a network into the transmission line. This is equivalent to the wave meeting an impedance differing from the line's characteristic impedance.

Although applicable at any frequency, S-parameters are mostly used for networks operating at radio frequency (RF) and microwave frequencies where signal power and energy considerations are more easily quantified than currents and voltages. S-parameters change with the measurement frequency, so frequency must be specified for any S-parameter measurements stated, in addition to the characteristic impedance or system impedance.

S-parameters are readily represented in matrix form and obey the rules of matrix algebra.

Background

Historically, an electrical network would have comprised a 'black box' containing various interconnected basic electrical circuit components or lumped elements such as resistors, capacitors, inductors and transistors. For the S-parameter definition, it is understood that a network may contain any components provided that the entire network behaves linearly with incident small signals. It may also include many typical communication system components or 'blocks' such as amplifiers, attenuators, filters, couplers and equalizers provided they are also operating under linear and defined conditions.

An electrical network to be described by S-parameters may have any number of ports. Ports are the points at which electrical currents either enter or exit the network. Sometimes these are referred to as pairs of terminals[5][6] so for example a 2-port network is equivalent to a 4-terminal network, though this terminology is unusual with S-parameters, because most S-parameter measurements are made at frequencies where coaxial or waveguide connectors are more appropriate.

The S-parameter matrix describing an N-port network will be square of dimension 'N' and will therefore contain  elements. At the test frequency each element or S-parameter is represented by a unitless complex number that represents magnitude and angle, i.e. amplitude and phase. The complex number may either be expressed in rectangular form or, more commonly, in polar form. The S-parameter magnitude may be expressed in linear form or logarithmic form. When expressed in logarithmic form, magnitude has the "dimensionless unit" of decibels. The S-parameter angle is most frequently expressed in degrees but occasionally in radians. Any S-parameter may be displayed graphically on a polar diagram by a dot for one frequency or a locus for a range of frequencies. If it applies to one port only (being of the form

elements. At the test frequency each element or S-parameter is represented by a unitless complex number that represents magnitude and angle, i.e. amplitude and phase. The complex number may either be expressed in rectangular form or, more commonly, in polar form. The S-parameter magnitude may be expressed in linear form or logarithmic form. When expressed in logarithmic form, magnitude has the "dimensionless unit" of decibels. The S-parameter angle is most frequently expressed in degrees but occasionally in radians. Any S-parameter may be displayed graphically on a polar diagram by a dot for one frequency or a locus for a range of frequencies. If it applies to one port only (being of the form  ), it may be displayed on an impedance or admittance Smith Chart normalised to the system impedance. The Smith Chart allows simple conversion between the

), it may be displayed on an impedance or admittance Smith Chart normalised to the system impedance. The Smith Chart allows simple conversion between the  parameter, equivalent to the voltage reflection coefficient and the associated (normalised) impedance (or admittance) 'seen' at that port.

parameter, equivalent to the voltage reflection coefficient and the associated (normalised) impedance (or admittance) 'seen' at that port.

The following information must be defined when specifying any S-parameter:

(1) The characteristic impedance (often 50  ).

).

(2) The allocation of port numbers.

(3) Conditions which may affect the network, such as frequency, temperature, control voltage, and bias current, where applicable.

The general S-parameter matrix

Definition

For a generic multi-port network, each of the ports is allocated an integer 'n' ranging from 1 to N, where N is the total number of ports. For port n, the associated S-parameter definition is in terms of incident and reflected 'power waves',  and

and  respectively.

respectively.

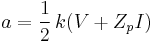

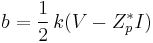

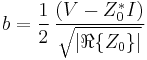

Kurokawa[7] defines the incident power wave for each port as

and the reflected wave for each port is defined as

where  is the diagonal matrix of the complex reference impedance for each port,

is the diagonal matrix of the complex reference impedance for each port,  is the elementwise complex conjugate of

is the elementwise complex conjugate of  ,

,  and

and  are respectively the column vectors of the voltages and currents at each port and

are respectively the column vectors of the voltages and currents at each port and

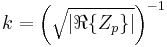

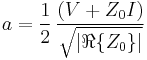

Sometimes it is useful to assume that the reference impedance is the same for all ports in which case the definitions of the incident and reflected waves may be simplified to

and

For all ports the reflected power waves may be defined in terms of the S-parameter matrix and the incident power waves by the following matrix equation:

where S is an N x N matrix the elements of which can be indexed using conventional matrix (mathematics) notation.

Reciprocity

A network will be reciprocal if it is passive and it contains only reciprocal materials that influence the transmitted signal. For example, attenuators, cables, splitters and combiners are all reciprocal networks and  in each case, or the S-parameter matrix will be equal to its transpose. Networks which include non-reciprocal materials in the transmission medium such as those containing magnetically biased ferrite components will be non-reciprocal. An amplifier is another example of a non-reciprocal network.

in each case, or the S-parameter matrix will be equal to its transpose. Networks which include non-reciprocal materials in the transmission medium such as those containing magnetically biased ferrite components will be non-reciprocal. An amplifier is another example of a non-reciprocal network.

An interesting property of 3-port networks, however, is that they cannot be simultaneously reciprocal, loss-free, and perfectly matched.[8]

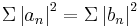

Lossless networks

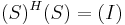

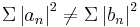

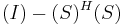

A lossless network is one which does not dissipate any power, or : . The sum of the incident powers at all ports is equal to the sum of the reflected powers at all ports. This implies that the S-parameter matrix is unitary, that is

. The sum of the incident powers at all ports is equal to the sum of the reflected powers at all ports. This implies that the S-parameter matrix is unitary, that is  , where

, where  is the conjugate transpose of

is the conjugate transpose of  and

and  is the identity matrix.

is the identity matrix.

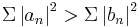

Lossy networks

A lossy passive network is one in which the sum of the incident powers at all ports is greater than the sum of the reflected powers at all ports. It therefore dissipates power, or : . In this case

. In this case  , and

, and  is positive definite.

is positive definite.

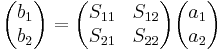

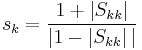

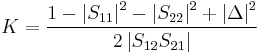

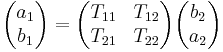

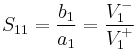

Two-Port S-Parameters

The S-parameter matrix for the 2-port network is probably the most commonly used and serves as the basic building block for generating the higher order matrices for larger networks.[9] In this case the relationship between the reflected, incident power waves and the S-parameter matrix is given by:

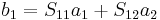

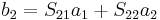

Expanding the matrices into equations gives:

and

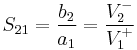

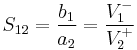

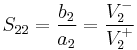

Each equation gives the relationship between the reflected and incident power waves at each of the network ports, 1 and 2, in terms of the network's individual S-parameters,  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  . If one considers an incident power wave at port 1 (

. If one considers an incident power wave at port 1 ( ) there may result from it waves exiting from either port 1 itself (

) there may result from it waves exiting from either port 1 itself ( ) or port 2 (

) or port 2 ( ). However if, according to the definition of S-parameters, port 2 is terminated in a load identical to the system impedance (

). However if, according to the definition of S-parameters, port 2 is terminated in a load identical to the system impedance ( ) then, by the maximum power transfer theorem,

) then, by the maximum power transfer theorem,  will be totally absorbed making

will be totally absorbed making  equal to zero. Therefore

equal to zero. Therefore

and

and

Similarly, if port 1 is terminated in the system impedance then  becomes zero, giving

becomes zero, giving

and

and

Each 2-port S-parameter has the following generic descriptions:

is the input port voltage reflection coefficient

is the input port voltage reflection coefficient is the reverse voltage gain

is the reverse voltage gain is the forward voltage gain

is the forward voltage gain is the output port voltage reflection coefficient

is the output port voltage reflection coefficient

S-Parameter properties of 2-port networks

An amplifier operating under linear (small signal) conditions is a good example of a non-reciprocal network and a matched attenuator is an example of a reciprocal network. In the following cases we will assume that the input and output connections are to ports 1 and 2 respectively which is the most common convention. The nominal system impedance, frequency and any other factors which may influence the device, such as temperature, must also be specified.

Complex linear gain

The complex linear gain G is given by

.

.

That is simply the voltage gain as a linear ratio of the output voltage divided by the input voltage, all values expressed as complex quantities.

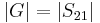

Scalar linear gain

The scalar linear gain (or linear gain magnitude) is given by

.

.

That is simply the scalar voltage gain as a linear ratio of the output voltage and the input voltage. As this is a scalar quantity, the phase is not relevant in this case.

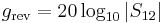

Scalar logarithmic gain

The scalar logarithmic (decibel or dB) expression for gain (g) is

dB.

dB.

This is more commonly used than scalar linear gain and a positive quantity is normally understood as simply a 'gain'... A negative quantity can be expressed as a 'negative gain' or more usually as a 'loss' equivalent to its magnitude in dB. For example, a 10 m length of cable may have a gain of - 1 dB at 100 MHz or a loss of 1 dB at 100 MHz.

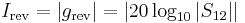

Insertion loss

In case the two measurement ports use the same reference impedance, the insertion loss ( ) is the dB expression of the transmission coefficient

) is the dB expression of the transmission coefficient  . It is thus given by:[10]

. It is thus given by:[10]

dB.

dB.

It is the extra loss produced by the introduction of the DUT between the 2 reference planes of the measurement. Notice that the extra loss can be introduced by intrinsic loss in the DUT and/or mismatch. In case of extra loss the insertion loss is defined to be positive.

Input return loss

Input return loss ( ) is a scalar measure of how close the actual input impedance of the network is to the nominal system impedance value and, expressed in logarithmic magnitude, is given by

) is a scalar measure of how close the actual input impedance of the network is to the nominal system impedance value and, expressed in logarithmic magnitude, is given by

dB.

dB.

By definition, return loss is a positive scalar quantity implying the 2 pairs of magnitude (|) symbols. The linear part,  is equivalent to the reflected voltage magnitude divided by the incident voltage magnitude.

is equivalent to the reflected voltage magnitude divided by the incident voltage magnitude.

Output return loss

The output return loss ( ) has a similar definition to the input return loss but applies to the output port (port 2) instead of the input port. It is given by

) has a similar definition to the input return loss but applies to the output port (port 2) instead of the input port. It is given by

dB.

dB.

Reverse gain and reverse isolation

The scalar logarithmic (decibel or dB) expression for reverse gain ( ) is:

) is:

dB.

dB.

Often this will be expressed as reverse isolation ( ) in which case it becomes a positive quantity equal to the magnitude of

) in which case it becomes a positive quantity equal to the magnitude of  and the expression becomes:

and the expression becomes:

dB.

dB.

Voltage reflection coefficient

The voltage reflection coefficient at the input port ( ) or at the output port (

) or at the output port ( ) are equivalent to

) are equivalent to  and

and  respectively, so

respectively, so

and

and  .

.

As  and

and  are complex quantities, so are

are complex quantities, so are  and

and  .

.

Voltage reflection coefficients are complex quantities and may be graphically represented on polar diagrams or Smith Charts

See also the Reflection Coefficient article.

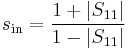

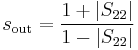

Voltage standing wave ratio

The voltage standing wave ratio (VSWR) at a port, represented by the lower case 's', is a similar measure of port match to return loss but is a scalar linear quantity, the ratio of the standing wave maximum voltage to the standing wave minimum voltage. It therefore relates to the magnitude of the voltage reflection coefficient and hence to the magnitude of either  for the input port or

for the input port or  for the output port.

for the output port.

At the input port, the VSWR ( ) is given by

) is given by

At the output port, the VSWR ( ) is given by

) is given by

This is correct for reflection coefficients with a magnitude no greater than unity, which is usually the case. A reflection coefficient with a magnitude greater than unity, such as in a tunnel diode amplifier, will result in a negative value for this expression. VSWR, however, from its definition, is always positive. A more correct expression for port k of a multiport is;

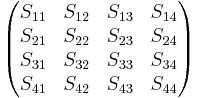

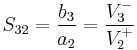

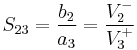

4-Port S-Parameters

4 Port S Parameters are used to characterize 4 port networks. They include information regarding the reflected and incident power waves between the 4 ports of the network.

They are commonly used to analyze a pair of coupled transmission lines to determine the amount of cross-talk between them, if they are driven by two separate single ended signals, or the reflected and incident power of a differential signal driven across them. Many specifications of high speed differential signals define a communication channel in terms of the 4-Port S-Parameters, for example the 10-Gigabit Attachment Unit Interface (XAUI), SATA, PCI-X, and InfiniBand systems.

4-Port Mixed-Mode S-Parameters

4-Port mixed-Mode S-Parameters characterize a 4 port network in terms of the response of the network to common mode and differential stimulus signals. The following table displays the 4-Port Mixed-Mode S-Parameters.

| Stimulus | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Differential | Common Mode | |||||

| Port 1 | Port 2 | Port 1 | Port 2 | |||

| Response | Differential | Port 1 | SDD11 | SDD12 | SDC11 | SDC12 |

| Port 2 | SDD21 | SDD22 | SDC21 | SDC22 | ||

| Common Mode | Port 1 | SCD11 | SCD12 | SCC11 | SCC12 | |

| Port 2 | SCD21 | SCD22 | SCC21 | SCC22 | ||

Note the format of the parameter notation SXYab, where “S” stands for scatttering parameter or S-parameter, “X” is the response mode (differential or common), “Y” is the stimulus mode (differential or common), “a” is the response (output) port and b is the stimulus (input) port. This is the typical nomenclature for scattering parameters.

The first quadrant is defined as the upper left 4 parameters describing the differential stimulus and differential response characteristics of the device under test. This is the actual mode of operation for most high-speed differential interconnects and is the quadrant that receives the most attention. It includes input differential return loss (SDD11), input differential insertion loss (SDD21), output differential return loss (SDD22) and output differential insertion loss (SDD12). Some benefits of differential signal processing are;

- reduced electromagnetic interference susceptibility

- reduction in electromagnetic radiation from balanced differential circuit

- even order differential distortion products transformed to common mode signals

- factor of two increase in voltage level relative to single-ended

- rejection to common mode supply and ground noise encoding onto differential signal

The second and third quadrants are the upper right and lower left 4 parameters, respectively. These are also referred to as the cross-mode quadrants. This is because they fully characterize any mode conversion occurring in the device under test, whether it is common-to-differential SDCab conversion (EMI susceptibility for an intended differential signal SDD transmission application) or differential-to-common SCDab conversion (EMI radiation for a differential application). Understanding mode conversion is very helpful when trying to optimize the design of interconnects for gigabit data throughput.

The fourth quadrant is the lower right 4 parameters and describes the performance characteristics of the common-mode signal SCCab propagating through the device under test. For a properly designed SDDab differential device there should be minimal common-mode output SCCab. However, the fourth quadrant common-mode response data is a measure of common-mode transmission response and used in a ratio with the differential transmission response to determine the network common-mode rejection. This common mode rejection is an important benefit of differential signal processing and can be reduced to one in some differential circuit implementations.[11][12]

S-parameters in amplifier design

The reverse isolation parameter  determines the level of feedback from the output of an amplifier to the input and therefore influences its stability (its tendency to refrain from oscillation) together with the forward gain

determines the level of feedback from the output of an amplifier to the input and therefore influences its stability (its tendency to refrain from oscillation) together with the forward gain  . An amplifier with input and output ports perfectly isolated from each other would have infinite scalar log magnitude isolation or the linear magnitude of

. An amplifier with input and output ports perfectly isolated from each other would have infinite scalar log magnitude isolation or the linear magnitude of  would be zero. Such an amplifier is said to be unilateral. Most practical amplifiers though will have some finite isolation allowing the reflection coefficient 'seen' at the input to be influenced to some extent by the load connected on the output. An amplifier which is deliberately designed to have the smallest possible value of

would be zero. Such an amplifier is said to be unilateral. Most practical amplifiers though will have some finite isolation allowing the reflection coefficient 'seen' at the input to be influenced to some extent by the load connected on the output. An amplifier which is deliberately designed to have the smallest possible value of  is often called a buffer amplifier.

is often called a buffer amplifier.

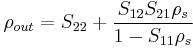

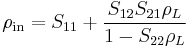

Suppose the output port of a real (non-unilateral or bilateral) amplifier is connected to an arbitrary load with a reflection coefficient of  . The actual reflection coefficient 'seen' at the input port

. The actual reflection coefficient 'seen' at the input port  will be given by[13]

will be given by[13]

.

.

If the amplifier is unilateral then  and

and  or, to put it another way, the output loading has no effect on the input.

or, to put it another way, the output loading has no effect on the input.

A similar property exists in the opposite direction, in this case if  is the reflection coefficient seen at the output port and

is the reflection coefficient seen at the output port and  is the reflection coefficient of the source connected to the input port.

is the reflection coefficient of the source connected to the input port.

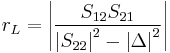

Port loading conditions for an amplifier to be unconditionally stable

An amplifier is unconditionally stable if a load or source of any reflection coefficient can be connected without causing instability. This condition occurs if the magnitudes of the reflection coefficients at the source, load and the amplifier's input and output ports are simultaneously less than unity. An important requirement that is often overlooked is that the amplifier be a linear network with no poles in the right half plane.[14] Instability can cause severe distortion of the amplifier's gain frequency response or, in the extreme, oscillation. To be unconditionally stable at the frequency of interest, an amplifier must satisfy the following 4 equations simultaneously:[15]

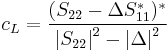

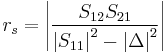

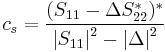

The boundary condition for when each of these values is equal to unity may be represented by a circle drawn on the polar diagram representing the (complex) reflection coefficient, one for the input port and the other for the output port. Often these will be scaled as Smith Charts. In each case coordinates of the circle centre and the associated radius are given by the following equations:

values for

values for  (output stability circle)

(output stability circle)

Radius

Center

values for

values for  (input stability circle)

(input stability circle)

Radius

Center

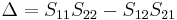

where, in both cases

and the superscript star (*) indicates a complex conjugate.

The circles are in complex units of reflection coefficient so may be drawn on impedance or admittance based Smith Charts normalised to the system impedance. This serves to readily show the regions of normalised impedance (or admittance) for predicted unconditional stability. Another way of demonstrating unconditional stability is by means of the Rollet stability factor ( ), defined as

), defined as

The condition of unconditional stability is achieved when  and

and

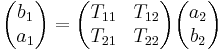

Scattering transfer parameters

The Scattering transfer parameters or T-parameters of a 2-port network are expressed by the T-parameter matrix and are closely related to the corresponding S-parameter matrix. The T-parameter matrix is related to the incident and reflected normalised waves at each of the ports as follows:

However, they could be defined differently, as follows :

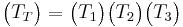

The RF Toolbox add-on to MATLAB[16] and several books (for example "Network scattering parameters"[17]) use this last definition, so caution is necessary. The "From S to T" and "From T to S" paragraphs in this article are based on the first definition. Adaptation to the second definition is trivial (interchanging T11 for T22, and T12 for T21). The advantage of T-parameters compared to S-parameters is that they may be used to readily determine the effect of cascading 2 or more 2-port networks by simply multiplying the associated individual T-parameter matrices. If the T-parameters of say three different 2-port networks 1, 2 and 3 are  ,

,  and

and  respectively then the T-parameter matrix for the cascade of all three networks (

respectively then the T-parameter matrix for the cascade of all three networks ( ) in serial order is given by:

) in serial order is given by:

As with S-parameters, T-parameters are complex values and there is a direct conversion between the two types. Although the cascaded T-parameters is a simple matrix multiplication of the individual T-parameters, the conversion for each network's S-parameters to the corresponding T-parameters and the conversion of the cascaded T-parameters back to the equivalent cascaded S-parameters, which are usually required, is not trivial. However once the operation is completed, the complex full wave interactions between all ports in both directions will be taken into account. The following equations will provide conversion between S and T parameters for 2-port networks.[18]

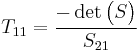

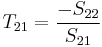

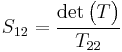

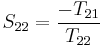

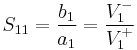

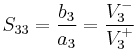

From S to T:

From T to S

Where  indicates the determinant of the matrix

indicates the determinant of the matrix  .

.

1-port S-parameters

The S-parameter for a 1-port network is given by a simple 1 x 1 matrix of the form  where n is the allocated port number. To comply with the S-parameter definition of linearity, this would normally be a passive load of some type.

where n is the allocated port number. To comply with the S-parameter definition of linearity, this would normally be a passive load of some type.

Higher-order S-parameter matrices

Higher order S-parameters for pairs of dissimilar ports ( ), where

), where  may be deduced similarly to those for 2-port networks by considering pairs of ports in turn, in each case ensuring that all of the remaining (unused) ports are loaded with an impedance identical to the system impedance. In this way the incident power wave for each of the unused ports becomes zero yielding similar expressions to those obtained for the 2-port case. S-parameters relating to single ports only (

may be deduced similarly to those for 2-port networks by considering pairs of ports in turn, in each case ensuring that all of the remaining (unused) ports are loaded with an impedance identical to the system impedance. In this way the incident power wave for each of the unused ports becomes zero yielding similar expressions to those obtained for the 2-port case. S-parameters relating to single ports only ( ) require all of the remaining ports to be loaded with an impedance identical to the system impedance therefore making all of the incident power waves zero except that for the port under consideration. In general therefore we have:

) require all of the remaining ports to be loaded with an impedance identical to the system impedance therefore making all of the incident power waves zero except that for the port under consideration. In general therefore we have:

and

For example, a 3-port network such as a 2-way splitter would have the following S-parameter definitions

Measurement of S-parameters

Vector network analyzer

The diagram shows the essential parts of a typical 2-port vector network analyzer (VNA). The two ports of the device under test (DUT) are denoted port 1 (P1) and port 2 (P2). The test port connectors provided on the VNA itself are precision types which will normally have to be extended and connected to P1 and P2 using precision cables 1 and 2, PC1 and PC2 respectively and suitable connector adaptors A1 and A2 respectively.

The test frequency is generated by a variable frequency CW source and its power level is set using a variable attenuator. The position of switch SW1 sets the direction that the test signal passes through the DUT. Initially consider that SW1 is at position 1 so that the test signal is incident on the DUT at P1 which is appropriate for measuring  and

and  . The test signal is fed by SW1 to the common port of splitter 1, one arm (the reference channel) feeding a reference receiver for P1 (RX REF1) and the other (the test channel) connecting to P1 via the directional coupler DC1, PC1 and A1. The third port of DC1 couples off the power reflected from P1 via A1 and PC1, then feeding it to test receiver 1 (RX TEST1). Similarly, signals leaving P2 pass via A2, PC2 and DC2 to RX TEST2. RX REF1, RX TEST1, RX REF2 and RXTEST2 are known as coherent receivers as they share the same reference oscillator, and they are capable of measuring the test signal's amplitude and phase at the test frequency. All of the complex receiver output signals are fed to a processor which does the mathematical processing and displays the chosen parameters and format on the phase and amplitude display. The instantaneous value of phase includes both the temporal and spatial parts, but the former is removed by virtue of using 2 test channels, one as a reference and the other for measurement. When SW1 is set to position 2, the test signals are applied to P2, the reference is measured by RX REF2, reflections from P2 are coupled off by DC2 and measured by RX TEST2 and signals leaving P1 are coupled off by DC1 and measured by RX TEST1. This position is appropriate for measuring

. The test signal is fed by SW1 to the common port of splitter 1, one arm (the reference channel) feeding a reference receiver for P1 (RX REF1) and the other (the test channel) connecting to P1 via the directional coupler DC1, PC1 and A1. The third port of DC1 couples off the power reflected from P1 via A1 and PC1, then feeding it to test receiver 1 (RX TEST1). Similarly, signals leaving P2 pass via A2, PC2 and DC2 to RX TEST2. RX REF1, RX TEST1, RX REF2 and RXTEST2 are known as coherent receivers as they share the same reference oscillator, and they are capable of measuring the test signal's amplitude and phase at the test frequency. All of the complex receiver output signals are fed to a processor which does the mathematical processing and displays the chosen parameters and format on the phase and amplitude display. The instantaneous value of phase includes both the temporal and spatial parts, but the former is removed by virtue of using 2 test channels, one as a reference and the other for measurement. When SW1 is set to position 2, the test signals are applied to P2, the reference is measured by RX REF2, reflections from P2 are coupled off by DC2 and measured by RX TEST2 and signals leaving P1 are coupled off by DC1 and measured by RX TEST1. This position is appropriate for measuring  and

and  .

.

Calibration

Prior to making a VNA S-parameter measurement, the first essential step is to perform an accurate calibration appropriate to the intended measurements. Several types of calibration are normally available on the VNA. It is only in the last few years that VNAs have had the sufficiently advanced processing capability, at realistic cost, required to accomplish the more advanced types of calibration, including corrections for systematic errors.[19] The more basic types, often called 'response' calibrations, may be performed quickly but will only provide a result with moderate uncertainty. For improved uncertainty and dynamic range of the measurement a full 2 port calibration is required prior to DUT measurement. This will effectively eliminate all sources of systematic errors inherent in the VNA measurement system.

Minimization of systematic errors

Systematic errors are those which do not vary with time during a calibration. For a set of 2 port S-parameter measurements there are a total of 12 types of systematic errors which are measured and removed mathematically as part of the full 2 port calibration procedure. They are, for each port:

1. directivity and crosstalk

2. source and load mismatches

3. frequency response errors caused by reflection and transmission tracking within the test receivers

The calibration procedure requires initially setting up the VNA with all the cables, adaptors and connectors necessary to connect to the DUT but not at this stage connecting it. A calibration kit is used according to the connector types fitted to the DUT. This will normally include adaptors, nominal short circuits (SCs), open circuits (OCs) and load termination (TERM) standards of both connector sexes appropriate to the VNA and DUT connectors. Even with standards of high quality, when performing tests at the higher frequencies into the microwave range various stray capacitances and inductances will become apparent and cause uncertainty during the calibration. Data relating to the strays of the particular calibration kit used are measured at the factory traceable to national standards and the results are programmed into the VNA memory prior to performing the calibration.

The calibration procedure is normally software controlled, and instructs the operator to fit various calibration standards to the ends of the DUT connecting cables as well as making a through connection. At each step the VNA processor captures data across the test frequency range and stores it. At the end of the calibration procedure, the processor uses the stored data thus obtained to apply the systematic error corrections to all subsequent measurements made. All subsequent measurements are known as 'corrected measurements. At this point the DUT is connected and a corrected measurement of its S-parameters made.

Output format of measured and corrected S-parameter data

The S-parameter test data may be provided in many alternative formats, for example: list, graphical (Smith chart or polar diagram).

List format

In list format the measured and corrected S-parameters are tabulated against frequency. The most common list format is known as Touchstone or SNP, where N is the number of ports. Commonly text files containing this information would have the filename extension '.s2p'. An example of a Touchstone file listing for the full 2-port S-parameter data obtained for a device is shown below:

! Created Fri Jul 21 14:28:50 2005 # MHZ S DB R 50 ! SP1.SP 50 -15.4 100.2 10.2 173.5 -30.1 9.6 -13.4 57.2 51 -15.8 103.2 10.7 177.4 -33.1 9.6 -12.4 63.4 52 -15.9 105.5 11.2 179.1 -35.7 9.6 -14.4 66.9 53 -16.4 107.0 10.5 183.1 -36.6 9.6 -14.7 70.3 54 -16.6 109.3 10.6 187.8 -38.1 9.6 -15.3 71.4

Rows beginning with an exclamation mark contains only comments. The row beginning with the hash symbol indicates that in this case frequencies are in megahertz (MHZ), S-parameters are listed (S), magnitudes are in dB log magnitude (DB) and the system impedance is 50 Ohm (R 50). There are 9 columns of data. Column 1 is the test frequency in megahertz in this case. Columns 2, 4, 6 and 8 are the magnitudes of  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  respectively in dB. Columns 3, 5, 7 and 9 are the angles of

respectively in dB. Columns 3, 5, 7 and 9 are the angles of  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  respectively in degrees.

respectively in degrees.

Graphical (Smith chart)

Any 2-port S-parameter may be displayed on a Smith chart using polar co-ordinates, but the most meaningful would be  and

and  since either of these may be converted directly into an equivalent normalized impedance (or admittance) using the characteristic Smith Chart impedance (or admittance) scaling appropriate to the system impedance.

since either of these may be converted directly into an equivalent normalized impedance (or admittance) using the characteristic Smith Chart impedance (or admittance) scaling appropriate to the system impedance.

Graphical (polar diagram)

Any 2-port S-parameter may be displayed on a polar diagram using polar co-ordinates.

In either graphical format each S-parameter at a particular test frequency is displayed as a dot. If the measurement is a sweep across several frequencies a dot will appear for each. Many VNAs connect successive dots with straight lines for easier visibility.

Measuring S-parameters of a one-port network

The S-parameter matrix for a network with just one port will have just one element represented in the form  , where n is the number allocated to the port. Most VNAs provide a simple one-port calibration capability for one port measurement to save time if that is all that is required.

, where n is the number allocated to the port. Most VNAs provide a simple one-port calibration capability for one port measurement to save time if that is all that is required.

Measuring S-parameters of networks with more than 2 ports

VNAs designed for the simultaneous measurement of the S-parameters of networks with more than two ports are feasible but quickly become prohibitively complex and expensive. Usually their purchase is not justified since the required measurements can be obtained using a standard 2-port calibrated VNA with extra measurements followed by the correct interpretation of the results obtained. The required S-parameter matrix can be assembled from successive two port measurements in stages, two ports at a time, on each occasion with the unused ports being terminated in high quality loads equal to the system impedance. One risk of this approach is that the return loss or VSWR of the loads themselves must be suitably specified to be as close as possible to a perfect 50 Ohms, or whatever the nominal system impedance is. For a network with many ports there may be a temptation, on grounds of cost, to inadequately specify the VSWRs of the loads. Some analysis will be necessary to determine what the worst acceptable VSWR of the loads will be.

Assuming that the extra loads are specified adequately, if necessary, two or more of the S-parameter subscripts are modified from those relating to the VNA (1 and 2 in the case considered above) to those relating to the network under test (1 to N, if N is the total number of DUT ports). For example, if the DUT has 5 ports and a two port VNA is connected with VNA port 1 to DUT port 3 and VNA port 2 to DUT port 5, the measured VNA results ( ,

,  ,

,  and

and  ) would be equivalent to

) would be equivalent to  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  respectively, assuming that DUT ports 1, 2 and 4 were terminated in adequate 50 Ohm loads . This would provide 4 of the necessary 25 S-parameters.

respectively, assuming that DUT ports 1, 2 and 4 were terminated in adequate 50 Ohm loads . This would provide 4 of the necessary 25 S-parameters.

References

- ^ Pozar, David M. (2005); Microwave Engineering, Third Edition (Intl. Ed.); John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; pp 170-174. ISBN 0-471-44878-8.

- ^ Pozar, David M. (2005) (op. cit); pp 170-174.

- ^ Pozar, David M. (2005) (op. cit);pp 183-186.

- ^ Morton, A. H. (1985); Advanced Electrical Engineering;Pitman Publishing Ltd.; pp 33-72. ISBN 0-273-40172-6

- ^ Pozar, David M. (2005) (op. cit);p170.

- ^ Morton, A. H. (1985) (op. cit.); p 33

- ^ Kurokawa, K., "Power Waves and the Scattering Matrix", IEEE Trans. Micr. Theory & Tech., Mar. 1965, pp194-202

- ^ Pozar, David M. (2005) (op. cit); p 173.

- ^ J Choma & WK Chen (2007). Feedback networks: theory and circuit applications. Singapore: World Scientific. Chapter 3, p. 225 ff. ISBN 981-02-2770-1. http://books.google.com/?id=EWAIYfilhfwC&pg=PA225&dq=isbn=9810227701.

- ^ Collin, Robert E.; Foundations For Microwave Engineering, Second Edition

- ^ Backplane Channels and Correlation Between Their Frequency and Time Domain Performance

- ^ Bockelman, DE and Eisenstadt, WR "Combined differential and common-mode scattering parameteres: theory and simulation," MTT, IEEE transactions volume 43 issue 7 part 1–2 July 1995 pages 1530-1539

- ^ Gonzalez, Guillermo (1997); Microwave Transistor Amplifiers Analysis and Design, Second Edition; Prentice Hall NJ; pp 212-216. ISBN 0-13-254335-4.

- ^ J.M. Rollett, "Stability and Power-Gain Invariants of Linear Two-Ports", IRE Trans. on Circuit Theory vol. CT-9, pp. 29-32, March 1962

- ^ Gonzalez, Guillermo (op. cit.); pp 217-222

- ^ "RF Toolbox documentation". http://www.mathworks.com/access/helpdesk/help/toolbox/rf/index.html?/access/helpdesk/help/toolbox/rf/s2t.html.

- ^ R. Mavaddat. (1996). Network scattering parameter. Singapore: World Scientific. ISBN 978-9810223052. http://books.google.com/?id=287g2NkRYxUC&lpg=PA65&dq=T-parameters+&pg=PA66.

- ^ S-Parameter Design; Application Note AN 154; Agilent Technologies; p 14

- ^ Applying Error Correction to Network Analyzer Measurements; Agilent Application Note AN 1287-3, Agilent Technologies; p6

Bibliography

- Guillermo Gonzalez, "Microwave Transistor Amplifiers, Analysis and Design, 2nd. Ed.", Prentice Hall, New Jersey; ISBN 0135816467

- David M. Pozar, "Microwave Engineering", Third Edition, John Wiley & Sons Inc.; ISBN 0471170968

- William Eisenstadt, Bob Stengel, and Bruce Thompson, "Microwave Differential Circuit Design usign Mixed-Mode S-Parameters", Artech House; ISBN 1580539335; ISBN13: 9781580539333

- "S-Parameter Design", Application Note AN 154, Agilent Technologies

- "S-Parameter Techniques for Faster, More Accurate Network Design", Application Note AN 95-1, Agilent Technologies, PDF slides plus QuickTime video or scan of Richard W. Anderson's original article

- A. J. Baden Fuller, "An Introduction to Microwave Theory and Techniques, Second Edition, Pergammon International Library; ISBN 0-08-024227-8

- Ramo, Whinnery and Van Duzer, "Fields and Waves in Communications Electronics", John Wiley & Sons; ISBN 0-471-70721-X

- C. W. Davidson, "Transmission Lines for Communications with CAD Programs", Second Edition, Macmillan Education Ltd.; ISBN 0-333-47398-1

See also

- Admittance parameters

- Impedance parameters

- Two-port network

- X-parameters, a non-linear superset of S-parameters

- Belevitch's theorem