Parrotfish

| Parrotfish | |

|---|---|

| Bicolor parrotfish | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Superclass: | Osteichthyes |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Perciformes |

| Suborder: | Labroidei |

| Family: | Scaridae |

| Genera | |

|

Bolbometopon |

|

Parrotfishes are a group of fishes that traditionally had been considered a family (Scaridae), but now often are considered a subfamily (Scarinae) of the wrasses.[1] They are found in relatively shallow tropical and subtropical oceans throughout the world, but with the largest species richness in the Indo-Pacific. The approximately 90 species are found in coral reefs, rocky coasts and seagrass beds, and play a significant role in bioerosion.[2][3][4]

Contents |

Taxonomy

Traditionally, the parrotfishes have been considered a family level taxon, Scaridae. Although phylogenetic and evolutionary analysis of parrotfishes is still ongoing, it is now accepted that they are a clade in the tribe Cheilini, and are now commonly referred to as scarine labrids (subfamily Scarinae, family Labridae).[1] Some authorities have preferred to maintain the parrotfishes as a family level taxon,[5] resulting in Labridae not being monophyletic.

Characteristics

Parrotfish are named for their dentition, which also is distinct from that of other labrids. Their numerous teeth are arranged in a tightly packed mosaic on the external surface of the jaw bones, forming a parrot-like beak with which they rasp algae from coral and other rocky substrates[6] (which contributes to the process of bioerosion).

Although they are considered to be herbivores, parrotfish eat a wide variety of reef organisms, and they are not necessarily vegetarian. Species such as the green humphead parrotfish (Bolbometopon muricatum) include coral (polyps) in their diet.[6] Their feeding activity is important for the production and distribution of coral sands in the reef biome, and can prevent algae from choking coral. The teeth grow continuously, replacing material worn away by feeding.[7] The pharyngeal teeth grind up coral rock the fish ingest during feeding. After they digest the rock, they excrete it as sand, helping to create small islands and the sandy beaches of the Caribbean. One parrotfish can produce 90 kg of sand each year.[8]

Maximum sizes vary within the family, with the majority of species reaching 30–50 centimetres (12–20 in) in length. However, a few species reach lengths in excess of 1 m, and the green humphead parrotfish can reach up to 1.3 metres (4.3 ft).[9]

Life cycle

The development of parrotfish is complex and accompanied by a series of changes in color termed polychromatism. Almost all species are sequential hermaphrodites, starting as females (known as the initial phase) and then changing to males (the terminal phase). However, in many species, for example the stoplight parrotfish (Sparisoma viride), a number of individuals develop directly to males (i.e., they do not start as females). These directly developing males usually most resemble the initial phase, and often display a different mating strategy than the terminal phase males of the same species.[10] A few species, for example the Mediterranean parrotfish (S. cretense), are secondary gonochorist, meaning that some females do not change sex, and the ones that do, change from female to male while still immature (i.e., reproductively functioning females do not change to males).[11] The marbled parrotfish (Leptoscarus vaigiensis) is the only species of parrotfish known not to change sex.[7] In most species, the initial phase is dull red, brown or grey, while the terminal phase is vividly green or blue with bright pink or yellow patches. The remarkably different terminal and initial phases were first described as separate species in several cases, but there are also some species where the phases are similar.

In most parrotfish species, juveniles have a different color pattern from adults. Juveniles of some tropical species can alter their color temporarily to mimic other species. Feeding parrotfish of most tropical species form large schools grouped by size. Fights of several females presided over by a single male are normal in most species, the males vigorously defending their position from any challenge.

Parrotfish are pelagic spawners; they release many tiny buoyant eggs into the water, which become part of the plankton. The eggs float freely, settling into the coral until hatching.

Economic importance

A commercial fishery exists for some of the larger tropical species, particularly in the Indo-Pacific.

Protecting parrotfish is proposed as a way of saving Caribbean coral reefs from being overgrown with seaweed.[12]

Despite their striking colors, their feeding behavior renders them highly unsuitable for most marine aquaria.[7]

Mucus

A number of parrotfish species, including the queen parrotfish (Scarus vetula), secrete a mucus cocoon, particularly at night.[13] Prior to going to sleep, some species extrude mucus from their mouths, forming a protective cocoon that envelops the fish, presumably hiding its scent from potential predators.[14][15] This mucous envelope may also act as an early warning system, allowing the parrotfish to flee when it detects predators such as moray eels disturbing the protective membrane.[15] The skin itself is covered in another mucous substance that may have antioxidant properties that may serve to repair bodily damage,[13][15] or serve to repel parasites, in addition to providing protection from UV light.[13]

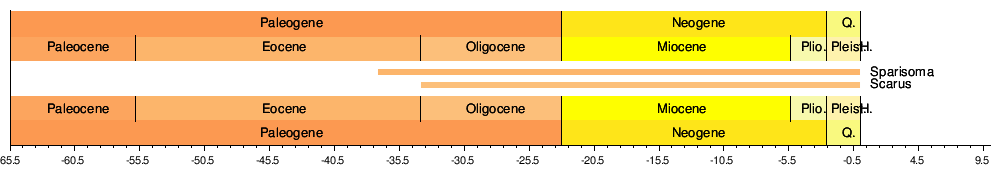

Timeline of genera

References

- ^ a b Westneat, M. W. and M. E. Alfaro (2005). "Phylogenetic relationships and evolutionary history of the reef fish family Labridae." Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 36(2): 201-428.

- ^ Streelman, J. T., M. E. Alfaro, et al. (2002). "Evolutionary History of The Parrotfishes: Biogeography, Ecomorphology, and Comparative Diversity." Evolution 56(5): 961-971.

- ^ Bellwood, D. R., Hoey, A. S., J. H. Choat. (2003). "Limited functional redundancy in high diversity systems: resilience and ecosystem function on coral reefs." Ecology Letters 6(4): 281–285.

- ^ Lokrantz, J., Nyström, Thyresson, M., M., C. Johansson. (2008). "The non-linear relationship between body size and function in parrotfishes." Coral reefs 27(4): 967-974.

- ^ Randall, J. E. (2007). Reef and Shore Fishes of the Hawaiian Islands. ISBN 9781929054039

- ^ a b Choat, J.H. & Bellwood, D.R. (1998). Paxton, J.R. & Eschmeyer, W.N.. ed. Encyclopedia of Fishes. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 209–211. ISBN 0-12-547665-5.

- ^ a b c Lieske, E., & R. Myers (1999). Coral Reef Fishes. 2nd edition. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00481-1

- ^ Thurman, H.V; Webber, H.H. (1984). "Chapter 12, Benthos on the Continental Shelf". Marine Biology. Charles E. Merrill Publishing. pp. 303–313. http://www.geology.iupui.edu/academics/CLASSES/G130/reefs/MB.htm. Accessed 2009-06-14.

- ^ Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2009). "Bolbometopon muricatum" in FishBase. December 2009 version.

- ^ Bester, C. Stoplight parrotfish. Florida Museum of Natural History, Ichthyology Department. Accessed 15-12-2009

- ^ Afonsoa, Moratoa & Santos (2008). Spatial patterns in reproductive traits of the temperate parrotfish Sparisoma cretense. Fisheries Research 90(1-3): 92-99

- ^ BBC Parrotfish to aid reef repair 1 November 2007

- ^ a b c Cerny-Chipman, E. "Distribution of Ultraviolet-Absorbing Sunscreen Compounds Across the Body Surface of Two Species of Scaridae." DigitalCollections@SIT 2007. Accessed 2009-06-21.

- ^ Langerhans, R.B. "Evolutionary consequences of predation: avoidance, escape, reproduction, and diversification." pp. 177-220 in Elewa, A.M.T. ed. Predation in organisms: a distinct phenomenon. Heidelberg, Germany, Springer-Verlag. 2007. Accessed 2009-06-21.

- ^ a b c Videlier, H.; Geertjes, G.J. and Videlier, J.J. (1999). "Biochemical characteristics and antibiotic properties of the mucous envelope of the queen parrotfish". Journal of Fish Biology. 54 (5): 1124–1127. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.1999.tb00864.x. http://www.rug.nl/staff/j.j.videler/1999VidelerGeertjesVideler.pdf. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- Sepkoski, Jack (2002). "A compendium of fossil marine animal genera". Bulletins of American Paleontology 364: p.560. http://strata.ummp.lsa.umich.edu/jack/showgenera.php?taxon=611&rank=class. Retrieved 2011-05-18.