Scale (descriptive set theory)

In the mathematical discipline of descriptive set theory, a scale is a certain kind of object defined on a set of points in some Polish space (for example, a scale might be defined on a set of real numbers). Scales were originally isolated as a concept in the theory of uniformization [1], but have found wide applicability in descriptive set theory, with applications such as establishing bounds on the possible lengths of wellorderings of a given complexity, and showing (under certain assumptions) that there are largest countable sets of certain complexities.

Contents |

Motivation

Scales arose from the question of finding a definable uniformization for a relation of a given complexity. That is, given a relation R, and supposing that for every x there is some y such that xRy, we would like an actual definable function f such that f(x) picks out a particular value y for which xRy.

If a relation — say, between points in the Baire space (which for purposes of descriptive set theory is more or less equivalent to the real numbers) — is "sufficiently definable", then it will have a so-called Suslin representation, a representation in terms of trees. A Suslin representation for a relation R in turn allows giving a definable uniformization for R (with the tree as a parameter to the definition); given x, it suffices to follow the leftmost branch of the tree of attempts to find a y such that xRy.

Scales are closely related to Suslin representations. In fact, if a subset of the Baire space has a κ-scale (that is, a scale all of whose norms take values less than κ; see the formal definition below), then it also has a κ-Suslin representation (that is, it can be represented by the infinite branches through a tree on κ×ω). Conversely, if a set has a κ-Suslin representation, then it has a κω-scale.[2]

The advantage of scales over unadorned Suslin representations is that arguments involving determinacy can use scales on simpler pointsets to obtain scales on more complicated ones, via arguments initiated by Yiannis N. Moschovakis.

Formal definition

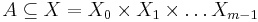

Given a pointset A contained in some product space

where each Xk is either the Baire space or a countably infinite discrete set, we say that a norm on A is a map from A into the ordinal numbers. Each norm has an associated prewellordering, where one element of A precedes another element if the norm of the first is less than the norm of the second.

A scale on A is a countably infinite collection of norms

with the following properties:

- If the sequence xi is such that

- xi is an element of A for each natural number i, and

- xi converges to an element xin the product space X, and

- for each natural number n there is an ordinal λn such that φn(xi)=λn for all sufficiently large i, then

- x is an element of A, and

- for each n, φn(x)≤λn.[3]

By itself, at least granted the axiom of choice, the existence of a scale on a pointset is trivial, as A can be wellordered and each φn can simply enumerate A. To make the concept useful, a definability criterion must be imposed on the norms (individually and together). Here "definability" is understood in the usual sense of descriptive set theory; it need not be definability in an absolute sense, but rather indicates membership in some pointclass of sets of reals. The norms φn themselves are not sets of reals, but the corresponding prewellorderings are (at least in essence).

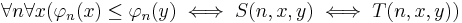

The idea is that, for a given pointclass Γ, we want the prewellorderings below a given point in A to be uniformly represented both as a set in Γ and as one in the dual pointclass of Γ, relative to the "larger" point being an element of A. Formally, we say that the φn form a Γ-scale on A if they form a scale on A and there are ternary relations S and T such that, if y is an element of A, then

where S is in Γ and T is in the dual pointclass of Γ (that is, the complement of T is in Γ).[4] Note here that we think of φn(x) as being ∞ whenever x∉A; thus the condition φn(x)≤φn(y), for y∈A, also implies x∈A.

Note also that the definition does not imply that the collection of norms is in the intersection of Γ with the dual pointclass of Γ. This is because the three-way equivalence is conditional on y being an element of A. For y not in A, it might be the case that one or both of S(n,x,y) or T(n,x,y) fail to hold, even if x is in A (and therefore automatically φn(x)≤φn(y)=∞).

Applications

- This section is yet to be written

Scale property

The scale property is a strengthening of the prewellordering property. For pointclasses of a certain form, it implies that relations in the given pointclass have a uniformization that is also in the pointclass.

Periodicity

- This section is yet to be written

Notes

- ^ Kechris and Moschovakis 2008:28

- ^ Kechris and Moschovakis 2008:52–53

- ^ Kechris and Moschovakis 2008:37

- ^ Kechris and Moschovakis 2008:37, with harmless reworking

References

- Moschovakis, Yiannis N. (1980), Descriptive Set Theory, North Holland, ISBN 0-444-70199-0

- Kechris, Alexander S.; Moschovakis, Yiannis N. (2008), "Notes on the theory of scales", in Kechris, Alexander S.; Löwe, Benedikt; Steel, John R., Games, Scales and Suslin Cardinals: The Cabal Seminar, Volume I, Cambridge University Press, pp. 28–74, ISBN 978-0-521-89951-2