Short-time Fourier transform

The short-time Fourier transform (STFT), or alternatively short-term Fourier transform, is a Fourier-related transform used to determine the sinusoidal frequency and phase content of local sections of a signal as it changes over time.

Contents |

STFT

Continuous-time STFT

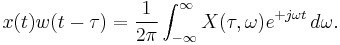

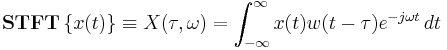

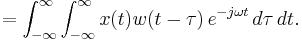

Simply, in the continuous-time case, the function to be transformed is multiplied by a window function which is nonzero for only a short period of time. The Fourier transform (a one-dimensional function) of the resulting signal is taken as the window is slid along the time axis, resulting in a two-dimensional representation of the signal. Mathematically, this is written as:

where w(t) is the window function, commonly a Hann window or Gaussian "hill" centered around zero, and x(t) is the signal to be transformed. X(τ,ω) is essentially the Fourier Transform of x(t)w(t-τ), a complex function representing the phase and magnitude of the signal over time and frequency. Often phase unwrapping is employed along either or both the time axis, τ, and frequency axis, ω, to suppress any jump discontinuity of the phase result of the STFT. The time index τ is normally considered to be "slow" time and usually not expressed in as high resolution as time t.

Discrete-time STFT

In the discrete time case, the data to be transformed could be broken up into chunks or frames (which usually overlap each other, to reduce artifacts at the boundary). Each chunk is Fourier transformed, and the complex result is added to a matrix, which records magnitude and phase for each point in time and frequency. This can be expressed as:

likewise, with signal x[n] and window w[n]. In this case, m is discrete and ω is continuous, but in most typical applications the STFT is performed on a computer using the Fast Fourier Transform, so both variables are discrete and quantized.

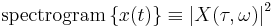

The magnitude squared of the STFT yields the spectrogram of the function:

See also the modified discrete cosine transform (MDCT), which is also a Fourier-related transform that uses overlapping windows.

Sliding DFT

If only a small number of ω are desired, or if the STFT is desired to be evaluated for every shift m of the window, then the STFT may be more efficiently evaluated using a sliding DFT algorithm.[1]

Inverse STFT

The STFT is invertible, that is, the original signal can be recovered from the transform by the Inverse STFT.

Continuous-time STFT

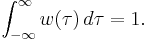

Given the width and definition of the window function w(t), we initially require the height of the window function to be scaled so that

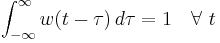

It easily follows that

and

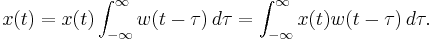

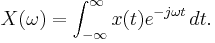

The continuous Fourier Transform is

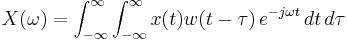

Substituting x(t) from above:

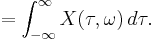

Swapping order of integration:

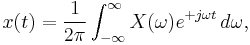

So the Fourier Transform can be seen as a sort of phase coherent sum of all of the STFTs of x(t). Since the inverse Fourier transform is

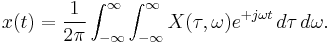

then x(t) can be recovered from X(τ,ω) as

or

It can be seen, comparing to above that windowed "grain" or "wavelet" of x(t) is

the inverse Fourier transform of X(τ,ω) for τ fixed.

Discrete-time STFT

Resolution issues

One of the downfalls of the STFT is that it has a fixed resolution. The width of the windowing function relates to how the signal is represented—it determines whether there is good frequency resolution (frequency components close together can be separated) or good time resolution (the time at which frequencies change). A wide window gives better frequency resolution but poor time resolution. A narrower window gives good time resolution but poor frequency resolution. These are called narrowband and wideband transforms, respectively.

This is one of the reasons for the creation of the wavelet transform (or multiresolution analysis in general), which can give good time resolution for high-frequency events, and good frequency resolution for low-frequency events, which is the type of analysis best suited for many real signals.

This property is related to the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, but it is not a direct relationship – see Gabor limit for discussion. The product of the standard deviation in time and frequency is limited. The boundary of the uncertainty principle (best simultaneous resolution of both) is reached with a Gaussian window function, as the Gaussian minimizes the Fourier uncertainty principle.

One can consider the STFT for varying window size as a two-dimensional domain (time and frequency), as illustrated in the example below, which can be calculated by varying the window size. However, this is no longer a strictly time–frequency representation – the kernel is not constant over the entire signal.

Example

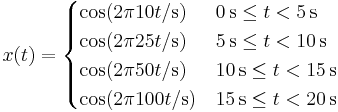

Using the following sample signal  that is composed of a set of four sinusoidal waveforms joined together in sequence. Each waveform is only composed of one of four frequencies (10, 25, 50, 100 Hz). The definition of

that is composed of a set of four sinusoidal waveforms joined together in sequence. Each waveform is only composed of one of four frequencies (10, 25, 50, 100 Hz). The definition of  is:

is:

Then it is sampled at 400 Hz. The following spectrograms were produced:

The 25 ms window allows us to identify a precise time at which the signals change but the precise frequencies are difficult to identify. At the other end of the scale, the 1000 ms window allows the frequencies to be precisely seen but the time between frequency changes is blurred.

Explanation

It can also be explained with reference to the sampling and Nyquist frequency.

Take a window of N samples from an arbitrary real-valued signal at sampling rate fs . Taking the Fourier transform produces N complex coefficients. Of these coefficients only half are useful (the last N/2 being the complex conjugate of the first N/2 in reverse order, as this is a real valued signal).

These N/2 coefficients represent the frequencies 0 to fs/2 (Nyquist) and two consecutive coefficients are spaced apart by fs/N Hz.

To increase the frequency resolution of the window the frequency spacing of the coefficients needs to be reduced. There are only two variables, but decreasing fs (and keeping N constant) will cause the window size to increase — since there are now fewer samples per unit time. The other alternative is to increase N, but this again causes the window size to increase. So any attempt to increase the frequency resolution causes a larger window size and therefore a reduction in time resolution—and vice-versa.

Application

STFTs as well as standard Fourier transforms and other tools are frequently used to analyze music. The spectrogram can, for example, show frequency on the horizontal axis, with the lowest frequencies at left, and the highest at the right. The height of each bar (augmented by color) represents the amplitude of the frequencies within that band. The depth dimension represents time, where each new bar was a separate distinct transform. Audio engineers use this kind of visual to gain information about an audio sample, for example, to locate the frequencies of specific noises (especially when used with greater frequency resolution) or to find frequencies which may be more or less resonant in the space where the signal was recorded. This information can be used for equalization or tuning other audio effects.

See also

Other time-frequency transforms:

- wavelet transform

- chirplet transform

- fractional Fourier transform

- Newland transform

- Constant Q transform

References

- ^ E. Jacobsen and R. Lyons, The sliding DFT, Signal Processing Magazine vol. 20, issue 2, pp. 74–80 (March 2003).

External links

- DiscreteTFDs – software for computing the short-time Fourier transform and other time-frequency distributions

- Singular Spectral Analysis - MultiTaper Method Toolkit - a free software program to analyze short, noisy time series.

- kSpectra Toolkit for Mac OS X from SpectraWorks

![\mathbf{STFT} \left \{ x[n] \right \} \equiv X(m,\omega) = \sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty} x[n]w[n-m]e^{-j \omega n}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/b8a341b5205029b7132e806677c6f5b0.png)

![X(\omega) = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \left[ \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} x(t) w(t-\tau) \, d\tau \right] \, e^{-j \omega t} \, dt](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/8262d82b5dc191e824e1f873c31e6ad3.png)

![= \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \left[ \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} x(t) w(t-\tau) \, e^{-j \omega t} \, dt \right] \, d\tau](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/7ee2f316ceb3d0e9f524f8d538da972d.png)

![x(t) = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \left[ \frac{1}{2 \pi} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} X(\tau, \omega) e^{%2Bj \omega t} \, d\omega \right] \, d\tau.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/dd4457409e90af6b68eb687c7cbbeb19.png)