Ruffini's rule

In mathematics, Ruffini's rule allows the rapid division of any polynomial by a binomial of the form x − r. It was described by Paolo Ruffini in 1809. Ruffini's rule is a special case of synthetic division when the divisor is a linear factor. The Horner scheme is a fast algorithm for dividing a polynomial by a linear polynomial with Ruffini's rule. See also polynomial long division for related background.

Contents |

Algorithm

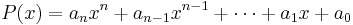

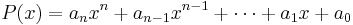

The rule establishes a method for dividing the polynomial

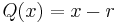

by the binomial

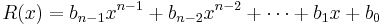

to obtain the quotient polynomial

and a remainder s.

The algorithm is in fact the long division of P(x) by Q(x).

To divide P(x) by Q(x):

1. Take the coefficients of P(x) and write them down in order. Then write r at the bottom left edge, just over the line:

| an an-1 ... a1 a0

|

r |

----|---------------------------------------------------------

|

|

2. Pass the leftmost coefficient (an) to the bottom, just under the line:

| an an-1 ... a1 a0

|

r |

----|---------------------------------------------------------

| an

|

| = bn-1

|

3. Multiply the rightmost number under the line by r and write it over the line and one position to the right:

| an an-1 ... a1 a0

|

r | bn-1r

----|---------------------------------------------------------

| an

|

| = bn-1

|

4. Add the two values just placed in the same column

| an an-1 ... a1 a0

|

r | bn-1r

----|---------------------------------------------------------

| an an-1+(bn-1r)

|

| = bn-1 = bn-2

|

5. Repeat steps 3 and 4 until no numbers remain

| an an-1 ... a1 a0

|

r | bn-1r ... b1r b0r

----|---------------------------------------------------------

| an an-1+(bn-1r) ... a1+b1r a0+b0r

|

| = bn-1 = bn-2 ... = b0 = s

|

The b values are the coefficients of the result (R(x)) polynomial, the degree of which is one less than that of P(x). The final value obtained, s, is the remainder. As shown in the polynomial remainder theorem, this remainder is equal to P(r), the value of the polynomial at r.

There is a numerical example below.

Uses of the rule

Ruffini's rule has many practical applications; most of them rely on simple division (as demonstrated below) or the common extensions given still further below.

Polynomial division by x − r

A worked example of polynomial division, as described above.

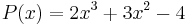

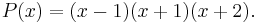

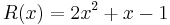

Let:

We want to divide P(x) by Q(x) using Ruffini's rule. The main problem is that Q(x) is not a binomial of the form x − r, but rather x + r. We must rewrite Q(x) in this way:

Now we apply the algorithm:

1. Write down the coefficients and r. Note that, as P(x) didn't contain a coefficient for x, we've written 0:

| 2 3 0 -4

|

-1 |

----|----------------------------

|

|

2. Pass the first coefficient down:

| 2 3 0 -4

|

-1 |

----|----------------------------

| 2

|

3. Multiply the last obtained value by r:

| 2 3 0 -4

|

-1 | -2

----|----------------------------

| 2

|

4. Add the values:

| 2 3 0 -4

|

-1 | -2

----|----------------------------

| 2 1

|

5. Repeat steps 3 and 4 until we've finished:

| 2 3 0 -4

|

-1 | -2 -1 1

----|----------------------------

| 2 1 -1 -3

|{result coefficients}{remainder}

So, if original number = divisor×quotient+remainder, then

, where

, where

and

and

Polynomial root-finding

The rational root theorem tells us that for a polynomial f(x) = anxn + an−1xn−1 + ... + a1x + a0 all of whose coefficients (an through a0) are integers, the real rational roots are always of the form p/q, where p is an integer divisor of a0 and q is an integer divisor of an. Thus if our polynomial is

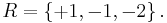

then the possible rational roots are all the integer divisors of a0 (−2):

(This example is simple because the polynomial is monic (i.e. an = 1); for non-monic polynomials the set of possible roots will include some fractions, but only a finite number of them since an and a0 only have a finite number of integer divisors each.) In any case, for monic polynomials, every rational root is an integer, and so every integer root is just a divisor of the constant term. It can be shown that this remains true for non-monic polynomials, i.e. to find the integer roots of any polynomials with integer coefficients, it suffices to check the divisors of the constant term.

So, setting r equal to each of these possible roots in turn, we will test-divide the polynomial by (x − r). If the resulting quotient has no remainder, we have found a root.

You can choose one of the following three methods: they will all yield the same results, with the exception that only through the second method and the third method (when applying Ruffini's rule to obtain a factorization) can you discover that a given root is repeated. (Remember that neither method will discover irrational or complex roots.)

Method 1

We try to divide P(x) by the binomial (x − each possible root). If the remainder is 0, the selected number is a root (and vice versa):

| +1 +2 -1 -2 | +1 +2 -1 -2

| |

+1 | +1 +3 +2 -1 | -1 -1 +2

----|---------------------------- ----|---------------------------

| +1 +3 +2 0 | +1 +1 -2 0

| +1 +2 -1 -2 | +1 +2 -1 -2

| |

+2 | +2 +8 +14 -2 | -2 0 +2

----|---------------------------- ----|---------------------------

| +1 +4 +7 +12 | +1 0 -1 0

Method 2

We start just as in Method 1 until we find a valid root. Then, instead of restarting the process with the other possible roots, we continue testing the possible roots against the result of the Ruffini on the valid root we've just found until we only have a coefficient remaining (remember that roots can be repeated: if you get stuck, try each valid root twice):

| +1 +2 -1 -2 | +1 +2 -1 -2

| |

-1 | -1 -1 +2 -1 | -1 -1 +2

----|--------------------------- ----|---------------------------

| +1 +1 -2 | 0 | +1 +1 -2 | 0

| |

+2 | +2 +6 +1 | +1 +2

------------------------- -------------------------

| +1 +3 |+4 | +1 +2 | 0

|

-2 | -2

-------------------

| +1 | 0

Method 3

- Determine the set of the possible integer or rational roots of the polynomial according to the rational root theorem.

- For each possible root r, instead of performing the division P(x)/(x -r), apply the polynomial remainder theorem, which states that the remainder of this division is P(r), i.e. the polynomial evaluated for x = r.

Thus, for each r in our set, r is actually a root of the polynomial if and only if P(r) = 0

This shows that finding integer and rational roots of a polynomial neither requires any division nor the application of Ruffini's rule.

However, once a valid root has been found, call it r1: you can apply Ruffini's rule to determine

Q(x) = P(x)/(x-r1).

This allows you to partially factorize the polynomial as

P(x) = (x -r1)·Q(X)

Any additional (rational) root of the polynomial is also a root of Q(x) and, of course, is still to be found among the possible roots determined earlier which have not yet been checked (any value already determined not to be a root of P(x) is not a root of Q(x) either; more formally, P(r)≠0 → Q(r)≠0 ).

Thus, you can proceed evaluating Q(r) instead of P(r), and (as long as you can find another root, r2) dividing Q(r) by (x-r2).

Even if you're only searching for roots, this allows you to evaluate polynomials of successively smaller degree, as the factorization proceeds.

If, as is often the case, you're also factorizing a polynomial of degree n, then:

- if you've found p=n rational solutions you end up with a complete factorization (see below) into p=n linear factors;

- if you've found p<n rational solutions you end up with a partial factorization (see below) into p linear factors and another non-linear factor of degree n-p, which, in turn, may have irrational or complex roots.

Remember to check out the limitations of the whole procedure.

Examples:

Finding roots without applying Ruffini's Rule

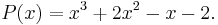

P(x) = x³ +2x² -x -2

Possible roots = {1, -1, 2, -2}

- P(1) = 0 → x1 = 1

- P(-1) = 0 → x2 = -1

- P(2) = 12 → 2 is not a root of the polynomial

and the remainder of (x³ +2x² -x -2)/(x-2) is 12

- P(-2) = 0 → x3 = -2

Finding roots applying Ruffini's Rule and obtaining a (complete) factorization

P(x) = x³ +2x² -x -2

Possible roots = {1, -1, 2, -2}

- P(1) = 0 → x1 = 1

Then, applying Ruffini's Rule:

(x³ +2x² -x -2) / (x -1) = (x² +3x +2) →

→ x³ +2x² -x -2 = (x-1)(x² +3x +2)

Here, r1=-1 and Q(x) = x² +3x +2

- Q(-1) = 0 → x2 = -1

Again, applying Ruffini's Rule:

(x² +3x +2) / (x +1) = (x +2) →

→ x³ +2x² -x -2 = (x-1)(x² +3x +2) = (x-1)(x+1)(x+2)

As it was possible to completely factorize the polynomial, it's clear that the last root is -2 (the previous procedure would have given the same result, with a final quotient of 1).

Polynomial factoring

Having used the "p/q" result above (or, to be fair, any other means) to find all the real rational roots of a particular polynomial, it is but a trivial step further to partially factor that polynomial using those roots. As is well-known, each linear factor (x − r) which divides a given polynomial corresponds with a root r, and vice versa.

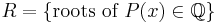

So if

is our polynomial; and

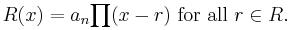

is our polynomial; and are the roots we have found, then consider the product

are the roots we have found, then consider the product

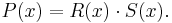

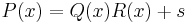

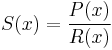

By the fundamental theorem of algebra, R(x) should be equal to P(x), if all the roots of P(x) are rational. But since we have been using a method which finds only rational roots, it is very likely that R(x) is not equal to P(x); it is very likely that P(x) has some irrational or complex roots not in R. So consider

, which can be calculated using polynomial long division.

, which can be calculated using polynomial long division.

If S(x) = 1, then we know R(x) = P(x) and we are done. Otherwise, S(x) will itself be a polynomial; this is another factor of P(x) which has no real rational roots. So write out the right-hand-side of the following equation in full:

We can call this a complete factorization of P(x) over Q (the rationals) if S(x) = 1. Otherwise, we only have a partial factorization of P(x) over Q, which may or may not be further factorable over the rationals; but which will certainly be further factorable over the reals or at worst the complex plane. (Note: by a "complete factorization" of P(x) over Q, we mean a factorization as a product of polynomials with rational coefficients, such that each factor is irreducible over Q, where "irreducible over Q" means that the factor cannot be written as the product of two non-constant polynomials with rational coefficients and smaller degree.)

Example 1: no remainder

Let

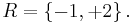

Using the methods described above, the rational roots of P(x) are:

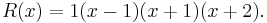

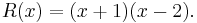

Then, the product of (x − each root) is

And P(x)/R(x):

Hence the factored polynomial is P(x) = R(x) · 1 = R(x):

Example 2: with remainder

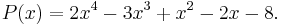

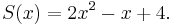

Let

Using the methods described above, the rational roots of P(x) are:

Then, the product of (x − each root) is

And P(x)/R(x)

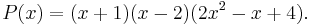

As  , the factored polynomial is P(x) = R(x) · S(x):

, the factored polynomial is P(x) = R(x) · S(x):

Factoring over the complexes

To completely factor a given polynomial over C, the complex numbers, we must know all of its roots (and that could include irrational and/or complex numbers). For example, consider the polynomial above:

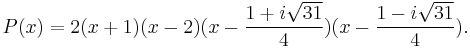

Extracting its rational roots and factoring it, we end with:

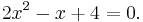

But that is not completely factored over C. If we need to factor our polynomial to a product of linear factors, we must deal with that quadratic factor

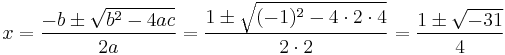

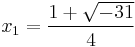

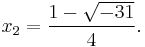

The easiest way is to use quadratic formula, which gives us

and the solutions

So the completely factored polynomial over C will be:

However, it should be noted that we cannot in every case expect things to be so easy; the quadratic formula's analogue for fourth-order polynomials is very messy and no such analogue exists for 5th-or-higher order polynomials. See Galois theory for a theoretical explanation of why this is so, and see numerical analysis for ways to approximate roots of polynomials numerically.

Limitations

It is entirely possible that, when looking for a given polynomial's roots, we might obtain a messy higher-order polynomial for S(x) which is further factorable over the rationals even before considering irrational or complex factorings. Consider the polynomial x5 − 3x4 + 3x3 − 9x2 + 2x − 6. Using Ruffini's method we will find only one root (x = 3); factoring it out gives us P(x) = (x4 + 3x2 + 2)(x − 3).

As explained above, if our assignment was to "factor into irreducibles over C" we know that would have to find some way to dissect the quartic and look for its irrational and/or complex roots. But if we were asked to "factor into irreducibles over Q", we might think we are done; but it is important to realize that this might not necessarily be the case.

For in this instance the quartic is actually factorable as the product of two quadratics (x2 + 1)(x2 + 2). These, at last, are irreducible over the rationals (and, indeed, the reals as well in this example); so now we are done; P(x) = (x2 + 1)(x2 + 2)(x − 3). In this instance it is in fact easy to factor our quartic by treating it as a biquadratic equation; but finding such factorings of a higher degree polynomial can be very difficult.

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Ruffini's rule" from MathWorld.

- Synthetic Division, an article by Elizabeth Stapel on Purple Math