Riemann zeta function

The Riemann zeta function, ζ(s), is a function of a complex variable s that analytically continues the sum of the infinite series  which converges when the real part of s is greater than 1. More general representations of ζ(s) for all s are given below. The Riemann zeta function plays a pivotal role in analytic number theory and has applications in physics, probability theory, and applied statistics.

which converges when the real part of s is greater than 1. More general representations of ζ(s) for all s are given below. The Riemann zeta function plays a pivotal role in analytic number theory and has applications in physics, probability theory, and applied statistics.

First results about this function were obtained by Leonhard Euler in the eighteenth century. It is named after Bernhard Riemann, who in the memoir "On the Number of Primes Less Than a Given Magnitude", published in 1859, established a relation between its zeros and the distribution of prime numbers.[1]

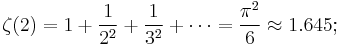

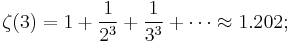

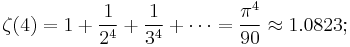

The values of the Riemann zeta function at even positive integers were computed by Euler. The first of them, ζ(2), provides a solution to the Basel problem. In 1979 Apéry proved the irrationality of ζ(3). The values at negative integer points, also found by Euler, are rational numbers and play an important role in the theory of modular forms. Many generalizations of the Riemann zeta function, such as Dirichlet series, Dirichlet L-functions and L-functions, are known.

Contents |

Definition

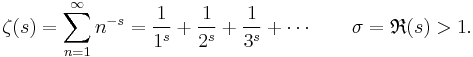

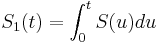

The Riemann zeta function ζ(s) is a function of a complex variable s = σ + it (here, s, σ and t are traditional notations associated to the study of the ζ-function). The following infinite series converges for all complex numbers s with real part greater than 1, and defines ζ(s) in this case:

The Riemann zeta function is defined as the analytic continuation of the function defined for σ > 1 by the sum of the preceding series.

Leonhard Euler considered the above series in 1740 for positive integer values of s, and later Chebyshev extended the definition to real s > 1.[2]

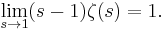

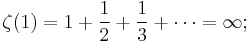

The above series is a prototypical Dirichlet series that converges absolutely to an analytic function for s such that σ > 1 and diverges for all other values of s. Riemann showed that the function defined by the series on the half-plane of convergence can be continued analytically to all complex values s ≠ 1. For s = 1 the series is the harmonic series which diverges to +∞, and

Thus the Riemann zeta function is a meromorphic function on the whole complex s-plane, which is holomorphic everywhere except for a simple pole at s = 1 with residue 1.

Specific values

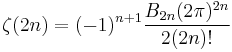

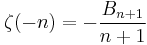

For any positive even number 2n,

where B2n is a Bernoulli number; for negative integers, one has

for n ≥ 1, so in particular ζ vanishes at the negative even integers because Bm = 0 for all odd m other than 1. No such simple expression is known for odd positive integers.

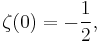

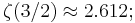

The values of the zeta function obtained from integral arguments are called zeta constants. The following are the most commonly used values of the Riemann zeta function.

- this is the harmonic series.

(sequence A078434 in OEIS)

(sequence A078434 in OEIS)

- this is employed in calculating the critical temperature for a Bose–Einstein condensate in a box with periodic boundary conditions, and for spin wave physics in magnetic systems.

(sequence A013661 in OEIS)

(sequence A013661 in OEIS)

- the demonstration of this equality is known as the Basel problem. The reciprocal of this sum answers the question: What is the probability that two numbers selected at random are relatively prime?[3]

(sequence A002117 in OEIS)

(sequence A002117 in OEIS)

-

- this is called Apéry's constant.

(sequence A0013662 in OEIS)

(sequence A0013662 in OEIS)

-

- Stefan–Boltzmann law and Wien approximation in physics.

Euler product formula

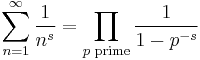

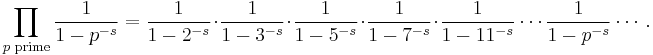

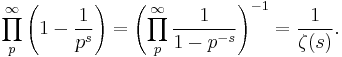

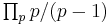

The connection between the zeta function and prime numbers was discovered by Leonhard Euler, who proved the identity

where, by definition, the left hand side is ζ(s) and the infinite product on the right hand side extends over all prime numbers p (such expressions are called Euler products):

Both sides of the Euler product formula converge for Re(s) > 1. The proof of Euler's identity uses only the formula for the geometric series and the fundamental theorem of arithmetic. Since the harmonic series, obtained when s = 1, diverges, Euler's formula (which becomes  ) implies that there are infinitely many primes.[4]

) implies that there are infinitely many primes.[4]

The Euler product formula can be used to calculate the asymptotic probability that s randomly selected integers are set-wise coprime. Intuitively, the probability that any single number is divisible by a prime (or any integer), p is 1/p. Hence the probability that s numbers are all divisible by this prime is 1/ps, and the probability that at least one of them is not is 1 − 1/ps. Now, for distinct primes, these divisibility events are mutually independent because the candidate divisors are coprime (a number is divisible by coprime divisors n and m if and only if it is divisible by nm, an event which occurs with probability 1/(nm).) Thus the asymptotic probability that s numbers are coprime is given by a product over all primes,

(More work is required to derive this result formally.)[5]

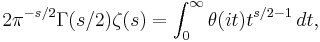

The functional equation

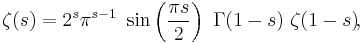

The Riemann zeta function satisfies the functional equation

where Γ(s) is the gamma function, which is an equality of meromorphic functions valid on the whole complex plane. This equation relates values of the Riemann zeta function at the points s and 1 − s. The functional equation (owing to the properties of sin) implies that ζ(s) has a simple zero at each even negative integer s = − 2n — these are the trivial zeros of ζ(s). For s an even positive integer, the product sin(πs/2)Γ(1−s) is regular and the functional equation relates the values of the Riemann zeta function at odd negative integers and even positive integers.

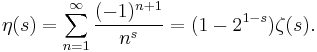

The functional equation was established by Riemann in his 1859 paper On the Number of Primes Less Than a Given Magnitude and used to construct the analytic continuation in the first place. An equivalent relationship had been conjectured by Euler over a hundred years earlier, in 1749, for the Dirichlet eta function (alternating zeta function)

Incidentally, this relation is interesting also because it actually exhibits ζ(s) as a Dirichlet series (of the η-function) which is convergent (albeit non-absolutely) in the larger half-plane σ > 0 (not just σ > 1), up to an elementary factor.

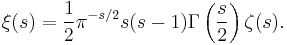

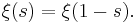

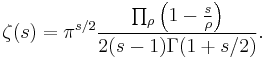

Riemann also found a symmetric version of the functional equation, given by first defining

The functional equation is then given by

(Riemann defined a similar but different function which he called ξ(t).)

Zeros, the critical line, and the Riemann hypothesis

The functional equation shows that the Riemann zeta function has zeros at −2, −4, ... . These are called the trivial zeros. They are trivial in the sense that their existence is relatively easy to prove, for example, from sin(πs/2) being 0 in the functional equation. The non-trivial zeros have captured far more attention because their distribution not only is far less understood but, more importantly, their study yields impressive results concerning prime numbers and related objects in number theory. It is known that any non-trivial zero lies in the open strip {s ∈ C: 0 < Re(s) < 1}, which is called the critical strip. The Riemann hypothesis, considered one of the greatest unsolved problems in mathematics, asserts that any non-trivial zero s has Re(s) = 1/2. In the theory of the Riemann zeta function, the set {s ∈ C: Re(s) = 1/2} is called the critical line. For the Riemann zeta function on the critical line, see Z-function.

The Hardy–Littlewood conjectures

In 1914 Godfrey Harold Hardy proved that  has infinitely many real zeros.

has infinitely many real zeros.

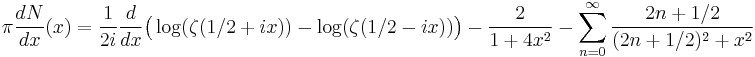

Let  be the total number of real zeros,

be the total number of real zeros,  be the total number of zeros of odd order of the function

be the total number of zeros of odd order of the function  , lying on the interval

, lying on the interval ![(0,T]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/5660568efb6ab2eb02a1ee97dd59ba56.png) .

.

The next two conjectures of Hardy and John Edensor Littlewood on the distance between real zeros of  and on the density of zeros of

and on the density of zeros of  on the intervals

on the intervals ![(T,T%2BH]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/fa2b3ed87882d01eb10f80daebb84c0b.png) for sufficiently great

for sufficiently great  ,

,  and with as less as possible value of

and with as less as possible value of  , where

, where  is an arbitrarily small number, open two new directions in the investigation of the Riemann zeta function:

is an arbitrarily small number, open two new directions in the investigation of the Riemann zeta function:

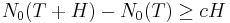

1. for any  there exists such

there exists such  that for

that for  and

and  the interval

the interval ![(T,T%2BH]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/fa2b3ed87882d01eb10f80daebb84c0b.png) contains a zero of odd order of the function

contains a zero of odd order of the function  .

.

2. for any  there exist

there exist  and

and  , such that for

, such that for  and

and  the inequality

the inequality  is true.

is true.

The Selberg conjecture

In 1942 Atle Selberg investigated the problem of Hardy–Littlewood 2 and proved that for any  there exists such

there exists such  and

and  , such that for

, such that for  and

and  the inequality

the inequality  is true.

is true.

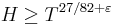

In his turn, Selberg claim a conjecture[6] that it's possible to decrease the value of the exponent  for

for  .

.

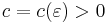

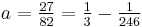

In 1984 Anatolii Alexeevitch Karatsuba proved[7][8][9] that for a fixed  satisfying the condition

satisfying the condition  , a sufficiently large

, a sufficiently large  and

and  ,

,  , the interval

, the interval  contains at least

contains at least  real zeros of the Riemann zeta function

real zeros of the Riemann zeta function  and therefore confirmed the Selberg conjecture.

and therefore confirmed the Selberg conjecture.

The estimates of Atle Selberg and Karatsuba can not be improved in respect of the order of growth as  .

.

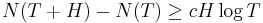

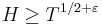

In 1992 A.A. Karatsuba proved,[10] that an analog of the Selberg conjecture holds for «almost all» intervals ![(T,T%2BH]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/fa2b3ed87882d01eb10f80daebb84c0b.png) ,

,  , where

, where  is an arbitrarily small fixed positive number. The Karatsuba method permits to investigate zeros of the Riemann zeta-function on «supershort» intervals of the critical line, that is, on the intervals

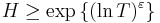

is an arbitrarily small fixed positive number. The Karatsuba method permits to investigate zeros of the Riemann zeta-function on «supershort» intervals of the critical line, that is, on the intervals ![(T,T%2BH]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/fa2b3ed87882d01eb10f80daebb84c0b.png) , the length

, the length  of which grows slower than any, even arbitrarily small degree

of which grows slower than any, even arbitrarily small degree  . In particular, he proved that for any given numbers

. In particular, he proved that for any given numbers  ,

,  satisfying the conditions

satisfying the conditions  almost all intervals

almost all intervals ![(T,T%2BH]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/fa2b3ed87882d01eb10f80daebb84c0b.png) for

for  contain at least

contain at least  zeros of the function

zeros of the function  . This estimate is quite close to the one that follows from the Riemann hypothesis.

. This estimate is quite close to the one that follows from the Riemann hypothesis.

Other results

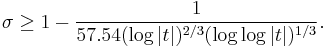

The location of the Riemann zeta function's zeros is of great importance in the theory of numbers. The prime number theorem is equivalent to the fact that there are no zeros of the zeta function on the Re(s) = 1 line[11]. A better result[12] is that ζ(σ + it) ≠ 0 whenever |t| ≥ 3 and

The strongest result of this kind one can hope for is the truth of the Riemann hypothesis, which would have many profound consequences in the theory of numbers.

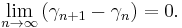

It is known that there are infinitely many zeros on the critical line. Littlewood showed that if the sequence (γn) contains the imaginary parts of all zeros in the upper half-plane in ascending order, then

The critical line theorem asserts that a positive percentage of the nontrivial zeros lies on the critical line.

In the critical strip, the zero with smallest non-negative imaginary part is 1/2 + i14.13472514... Directly from the functional equation one sees that the non-trivial zeros are symmetric about the axis Re(s) = 1/2. Furthermore, the fact that ζ(s) = ζ(s*)* for all complex s ≠ 1 (* indicating complex conjugation) implies that the zeros of the Riemann zeta function are symmetric about the real axis.

The statistics of the Riemann zeta zeros are a topic of interest to mathematicians because of their connection to big problems like the Riemann hypothesis, distribution of prime numbers, etc. Through connections with random matrix theory and quantum chaos, the appeal is even broader. The fractal structure of the Riemann zeta zero distribution has been studied using rescaled range analysis.[13] The self-similarity of the zero distribution is quite remarkable, and is characterized by a large fractal dimension of 1.9. This rather large fractal dimension is found over zeros covering at least fifteen orders of magnitude, and also for the zeros of other L-functions.

Various properties

For sums involving the zeta-function at integer and half-integer values, see rational zeta series.

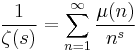

Reciprocal

The reciprocal of the zeta function may be expressed as a Dirichlet series over the Möbius function μ(n):

for every complex number s with real part > 1. There are a number of similar relations involving various well-known multiplicative functions; these are given in the article on the Dirichlet series.

The Riemann hypothesis is equivalent to the claim that this expression is valid when the real part of s is greater than 1/2.

Universality

The critical strip of the Riemann zeta function has the remarkable property of universality. This zeta-function universality states that there exists some location on the critical strip that approximates any holomorphic function arbitrarily well. Since holomorphic functions are very general, this property is quite remarkable.

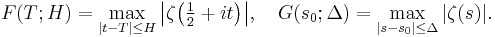

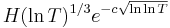

Estimates of the maximum of the modulus of the zeta function

Let the functions  and

and  be defined by the equalities

be defined by the equalities

Here  is a sufficiently large positive number,

is a sufficiently large positive number,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  . Estimating the values

. Estimating the values  and

and  from below shows, how large (in modulus) values

from below shows, how large (in modulus) values  can take on short intervals of the critical line or in small neighborhoods of points lying in the critical strip

can take on short intervals of the critical line or in small neighborhoods of points lying in the critical strip  .

.

The case  was studied by Ramachandra; the case

was studied by Ramachandra; the case  , where

, where  is a sufficiently large constant, is trivial.

is a sufficiently large constant, is trivial.

Karatsuba proved,[14][15] in particular, that if the values  and

and  exceed certain sufficiently small constants, then the estimates

exceed certain sufficiently small constants, then the estimates

hold, where  are certain absolute constants.

are certain absolute constants.

The argument of the Riemann zeta-function

The function  is called the argument of the Riemann zeta function. Here

is called the argument of the Riemann zeta function. Here  is the increment of an arbitrary continuous branch of

is the increment of an arbitrary continuous branch of  along the broken line joining the points

along the broken line joining the points  and

and  There are some theorems on properties of the function

There are some theorems on properties of the function  . Among those results[16][17] are the mean value theorems for

. Among those results[16][17] are the mean value theorems for  and its first integral

and its first integral  on intervals of the real line, and also the theorem claiming that every interval

on intervals of the real line, and also the theorem claiming that every interval ![(T,T%2BH]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/fa2b3ed87882d01eb10f80daebb84c0b.png) for

for  contains at least

contains at least

points where the function  changes sign. Earlier similar results were obtained by Atle Selberg for the case

changes sign. Earlier similar results were obtained by Atle Selberg for the case  .

.

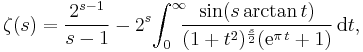

Representations

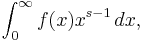

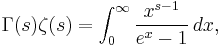

Mellin transform

The Mellin transform of a function ƒ(x) is defined as

in the region where the integral is defined. There are various expressions for the zeta-function as a Mellin transform. If the real part of s is greater than one, we have

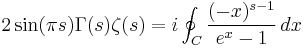

where Γ denotes the Gamma function. By modifying the contour Riemann showed that

for all s, where the contour C starts and ends at +∞ and circles the origin once.

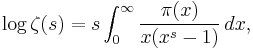

We can also find expressions which relate to prime numbers and the prime number theorem. If π(x) is the prime-counting function, then

for values with Re(s) > 1.

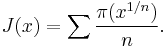

A similar Mellin transform involves the Riemann prime-counting function J(x), which counts prime powers pn with a weight of 1/n, so that

Now we have

These expressions can be used to prove the prime number theorem by means of the inverse Mellin transform. Riemann's prime-counting function is easier to work with, and π(x) can be recovered from it by Möbius inversion.

Theta functions

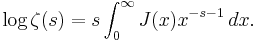

The Riemann zeta function can be given formally by a divergent Mellin transform

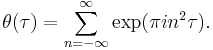

in terms of Jacobi's theta function

However this integral does not converge for any value of s and so needs to be regularized: this gives the following expression for the zeta function:

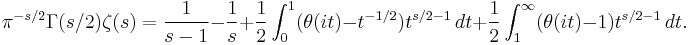

Laurent series

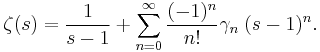

The Riemann zeta function is meromorphic with a single pole of order one at s = 1. It can therefore be expanded as a Laurent series about s = 1; the series development then is

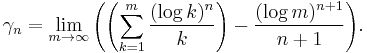

The constants γn here are called the Stieltjes constants and can be defined by the limit

The constant term γ0 is the Euler–Mascheroni constant.

Integral

For all  the integral relation

the integral relation

holds true, which may be used for a numerical evaluation of the Zeta-function.[18]

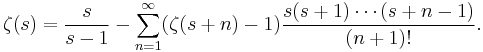

Rising factorial

Another series development using the rising factorial valid for the entire complex plane is

This can be used recursively to extend the Dirichlet series definition to all complex numbers.

The Riemann zeta function also appears in a form similar to the Mellin transform in an integral over the Gauss–Kuzmin–Wirsing operator acting on xs−1; that context gives rise to a series expansion in terms of the falling factorial.

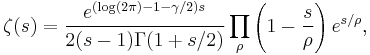

Hadamard product

On the basis of Weierstrass's factorization theorem, Hadamard gave the infinite product expansion

where the product is over the non-trivial zeros ρ of ζ and the letter γ again denotes the Euler–Mascheroni constant. A simpler infinite product expansion is

This form clearly displays the simple pole at s = 1, the trivial zeros at −2, −4, ... due to the gamma function term in the denominator, and the non-trivial zeros at s = ρ.

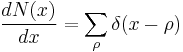

Logarithmic derivative on the critical strip

where  is the density of zeros of ζ on the critical strip 0 < Re(s) < 1 (δ is the Dirac delta distribution, and the sum is over the nontrivial zeros ρ of ζ).

is the density of zeros of ζ on the critical strip 0 < Re(s) < 1 (δ is the Dirac delta distribution, and the sum is over the nontrivial zeros ρ of ζ).

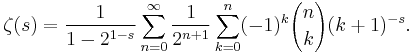

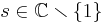

Globally convergent series

A globally convergent series for the zeta function, valid for all complex numbers s except s = 1 + 2πin/log(2) for some integer n, was conjectured by Konrad Knopp and proved by Helmut Hasse in 1930 (cf. Euler summation):

The series only appeared in an Appendix to Hasse's paper, and did not become generally known until it was rediscovered more than 60 years later (see Sondow, 1994).

Peter Borwein has shown a very rapidly convergent series suitable for high precision numerical calculations. The algorithm, making use of Chebyshev polynomials, is described in the article on the Dirichlet eta function.

Applications

The zeta function occurs in applied statistics (see Zipf's law and Zipf–Mandelbrot law).

Zeta function regularization is used as one possible means of regularization of divergent series in quantum field theory. In one notable example, the Riemann zeta-function shows up explicitly in the calculation of the Casimir effect. The zeta function is also useful for the analysis of dynamical systems, see [19].

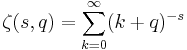

Generalizations

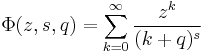

There are a number of related zeta functions that can be considered to be generalizations of the Riemann zeta function. These include the Hurwitz zeta function

(the convergent series representation was given by Helmut Hasse in 1930,[20] cf. Hurwitz zeta function), which coincides with the Riemann zeta function when q = 1 (note that the lower limit of summation in the Hurwitz zeta function is 0, not 1), the Dirichlet L-functions and the Dedekind zeta-function. For other related functions see the articles Zeta function and L-function.

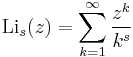

The polylogarithm is given by

which coincides with the Riemann zeta function when z = 1.

The Lerch transcendent is given by

which coincides with the Riemann zeta function when z = 1 and q = 1 (note that the lower limit of summation in the Lerch transcendent is 0, not 1).

The Clausen function Cls(θ) that can be chosen as the real or imaginary part of Lis(e iθ).

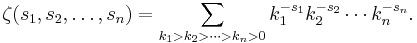

The multiple zeta functions are defined by

One can analytically continue these functions to the n-dimensional complex space. The special values of these functions are called multiple zeta values by number theorists and have been connected to many different branches in mathematics and physics.

See also

- Generalized Riemann hypothesis

- Riemann–Siegel theta function

- Prime zeta function

- 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + ···

Notes

- ^ This paper also contained the Riemann hypothesis, a conjecture about the distribution of complex zeros of the Riemann zeta function that is considered by many mathematicians to be the most important unsolved problem in pure mathematics.Bombieri, Enrico. "The Riemann Hypothesis - official problem description". Clay Mathematics Institute. http://www.claymath.org/millennium/Riemann_Hypothesis/riemann.pdf. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

- ^ Devlin, Keith (2002). The Millennium Problems: The Seven Greatest Unsolved Mathematical Puzzles of Our Time. New York: Barnes & Noble. pp. 43–47. ISBN 978-0760786598.

- ^ C. S. Ogilvy & J. T. Anderson Excursions in Number Theory, pp. 29–35, Dover Publications Inc., 1988 ISBN 0-486-25778-9

- ^ Charles Edward Sandifer, How Euler did it, The Mathematical Association of America, 2007, p. 193. ISBN 978-0-88385-563-8

- ^ J. E. Nymann (1972). "On the probability that k positive integers are relatively prime". Journal of Number Theory 4 (5): 469–473. doi:10.1016/0022-314X(72)90038-8.

- ^ Selberg, A. (1942). "On the zeros of Riemann's zeta-function". Shr. Norske Vid. Akad. Oslo (10): 1–59.

- ^ Karatsuba, A. A. (1984). "On the zeros of the function ζ(s) on short intervals of the critical line". Izv. Akad. Nauk SSSR, Ser. Mat. (48:3): 569–584.

- ^ Karatsuba, A. A. (1984). "The distribution of zeros of the function ζ(1/2+it)". Izv. Akad. Nauk SSSR, Ser. Mat. (48:6): 1214–1224.

- ^ Karatsuba, A. A. (1985). "On the zeros of the Riemann zeta-function on the critical line". Proc. Steklov Inst. Math. (167): 167–178.

- ^ Karatsuba, A. A. (1992). "On the number of zeros of the Riemann zeta-function lying in almost all short intervals of the critical line". Izv. Ross. Akad. Nauk, Ser. Mat. (56:2): 372–397.

- ^ Diamond, Harold G. (1982), "Elementary methods in the study of the distribution of prime numbers", Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 7 (3): 553–89, doi:10.1090/S0273-0979-1982-15057-1, MR670132.

- ^ Ford, K. (2002). "Vinogradov's integral and bounds for the Riemann zeta function". Proc. London Math. Soc. 85 (3): 565–633. doi:10.1112/S0024611502013655.

- ^ O. Shanker (2006). "Random matrices, generalized zeta functions and self-similarity of zero distributions". J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 39 (45): 13983–13997. Bibcode 2006JPhA...3913983S. doi:10.1088/0305-4470/39/45/008.

- ^ Karatsuba, A. A. (2001). "Lower bounds for the maximum modulus of ζ(s) in small domains of the critical strip". Mat. Zametki (70:5): 796–798.

- ^ Karatsuba, A. A. (2004). "Lower bounds for the maximum modulus of the Riemann zeta function on short segments of the critical line". Izv. Ross. Akad. Nauk, Ser. Mat. (68:8): 99–104.

- ^ Karatsuba, A. A. (1996). "Density theorem and the behavior of the argument of the Riemann zeta function". Mat. Zametki (60:3): 448–449.

- ^ Karatsuba, A. A. (1996). "On the function S(t)". Izv. Ross. Akad. Nauk, Ser. Mat. (60:5): 27–56.

- ^ Mathematik-Online-Kurs: Numerik - Numerische Integration der Riemannschen Zeta-Funktion

- ^ "Dynamical systems and number theory". http://empslocal.ex.ac.uk/people/staff/mrwatkin/zeta/spinchains.htm.

- ^ Hasse, Helmut (1930). "Ein Summierungsverfahren für die Riemannsche ζ-Reihe". Mathematische Zeitschrift 32 (1): 458–464. doi:10.1007/BF01194645

References

- Apostol, T. M. (2010), "Zeta and Related Functions", in Olver, Frank W. J.; Lozier, Daniel M.; Boisvert, Ronald F. et al., NIST Handbook of Mathematical Functions, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521192255, MR2723248, http://dlmf.nist.gov/25

- Riemann, Bernhard (1859). "Über die Anzahl der Primzahlen unter einer gegebenen Grösse". Monatsberichte der Berliner Akademie. http://www.maths.tcd.ie/pub/HistMath/People/Riemann/Zeta/.. In Gesammelte Werke, Teubner, Leipzig (1892), Reprinted by Dover, New York (1953).

- Hadamard, Jacques (1896). "Sur la distribution des zéros de la fonction ζ(s) et ses conséquences arithmétiques". Bulletin de la Societé Mathématique de France 14: 199–220.

- Hasse, Helmut (1930). "Ein Summierungsverfahren für die Riemannsche ζ-Reihe". Math. Z. 32: 458–464. doi:10.1007/BF01194645. MR1545177. (Globally convergent series expression.)

- E. T. Whittaker and G. N. Watson (1927). A Course in Modern Analysis, fourth edition, Cambridge University Press (Chapter XIII).

- H. M. Edwards (1974). Riemann's Zeta Function. Academic Press. ISBN 0-486-41740-9.

- G. H. Hardy (1949). Divergent Series. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

- A. Ivic (1985). The Riemann Zeta Function. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-80634-X.

- A.A. Karatsuba; S.M. Voronin (1992). The Riemann Zeta-Function. W. de Gruyter, Berlin.

- Hugh L. Montgomery; Robert C. Vaughan (2007). Multiplicative number theory I. Classical theory. Cambridge tracts in advanced mathematics. 97. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-84903-9. Chapter 10.

- Donald J. Newman (1998). Analytic number theory. GTM. 177. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-98308-2. Chapter 6.

- E. C. Titchmarsh (1986). The Theory of the Riemann Zeta Function, Second revised (Heath-Brown) edition. Oxford University Press.

- Jonathan Borwein, David M. Bradley, Richard Crandall (2000). "Computational Strategies for the Riemann Zeta Function" (PDF). J. Comp. App. Math. 121 (1–2): 247–296. doi:10.1016/S0377-0427(00)00336-8. http://www.maths.ex.ac.uk/~mwatkins/zeta/borwein1.pdf. Bibcode: 2000JCoAM.121..247B

- Cvijović, Djurdje; Klinowski, Jacek (2002). "Integral Representations of the Riemann Zeta Function for Odd-Integer Arguments". J. Comp. App. Math. 142 (2): 435–439. doi:10.1016/S0377-0427(02)00358-8. MR1906742. Bibcode: 2002JCoAM.142..435C

- Cvijović, Djurdje; Klinowski, Jacek (1997). "Continued-fraction expansions for the Riemann zeta function and polylogarithms". Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 125 (9): 2543–2550. doi:10.1090/S0002-9939-97-04102-6.

- Sondow, Jonathan (1994). "Analytic continuation of Riemann's zeta function and values at negative integers via Euler's transformation of series". Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 120 (120): 421–424. doi:10.1090/S0002-9939-1994-1172954-7.

- Zhao, Jianqiang (1999). "Analytic continuation of multiple zeta functions". Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 128 (5): 1275–1283. doi:10.1090/S0002-9939-99-05398-8. MR1670846.

- Raoh, Guo (1996). "The Distribution of the Logarithmic Derivative of the Riemann Zeta Function". Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society s3–72: 1–27. doi:10.1112/plms/s3-72.1.1.

- Mezo, Istvan; Dil, Ayhan (2010). "Hyperharmonic series involving Hurwitz zeta function". Journal of Number Theory 130 (2): 360–369. doi:10.1016/j.jnt.2009.08.005. MR2564902.

External links

- Riemann Zeta Function, in Wolfram Mathworld — an explanation with a more mathematical approach

- Tables of selected zeros

- Prime Numbers Get Hitched A general, non-technical description of the significance of the zeta function in relation to prime numbers.

- X-Ray of the Zeta Function Visually oriented investigation of where zeta is real or purely imaginary.

- Formulas and identities for the Riemann Zeta function functions.wolfram.com

- Riemann Zeta Function and Other Sums of Reciprocal Powers, section 23.2 of Abramowitz and Stegun

- The Riemann Hypothesis - A Visual Exploration — a visual exploration of the Riemann Hypothesis and Zeta Function

|

||||||||||||||||||||