Reverberation

Reverberation is the persistence of sound in a particular space after the original sound is removed.[1] A reverberation, or reverb, is created when a sound is produced in an enclosed space causing a large number of echoes to build up and then slowly decay as the sound is absorbed by the walls and air.[2] This is most noticeable when the sound source stops but the reflections continue, decreasing in amplitude, until they can no longer be heard. The length of this sound decay, or reverberation time, receives special consideration in the architectural design of large chambers, which need to have specific reverberation times to achieve optimum performance for their intended activity.[3] In comparison to a distinct echo that is 50 to 100 ms after the initial sound, reverberation is many thousands of echoes that arrive in very quick succession (.01 – 1 ms between echoes). As time passes, the volume of the many echoes is reduced until the echoes cannot be heard at all.

Contents |

Reverberation time

RT60 is the time required for reflections of a direct sound to decay by 60 dB below the level of the direct sound. Reverberation time is frequently stated as a single value however it can be measured as a wide band signal (20 Hz to 20kHz) or more precisely in narrow bands (one octave, 1/3 octave, 1/6 octave, etc.). Typically, the reverb time measured in narrow bands will differ depending on the frequency band being measured. It is usually helpful to know what range of frequencies are being described by a reverberation time measurement.

In the late 19th century, Wallace Clement Sabine started experiments at Harvard University to investigate the impact of absorption on the reverberation time. Using a portable wind chest and organ pipes as a sound source, a stopwatch and his ears, he measured the time from interruption of the source to inaudibility (roughly 60 dB). He found that the reverberation time is proportional to the dimensions of room and inversely proportional to the amount of absorption present.

The optimum reverberation time for a space in which music is played depends on the type of music that is to be played in the space. Rooms used for speech typically need a shorter reverberation time so that speech can be understood more clearly. If the reflected sound from one syllable is still heard when the next syllable is spoken, it may be difficult to understand what was said.[4] "Cat", "Cab", and "Cap" may all sound very similar. If on the other hand the reverberation time is too short, tonal balance and loudness may suffer. Reverberation effects are often used in studios to add depth to sounds. Reverberation changes the perceived harmonic structure of a note, but does not alter the pitch.

Basic factors that affect a room's reverberation time include the size and shape of the enclosure as well as the materials used in the construction of the room. Every object placed within the enclosure can also affect this reverberation time, including people and their belongings.

Sabine equation

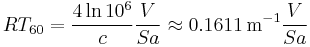

Sabine's reverberation equation was developed in the late 1890s in an empirical fashion. He established a relationship between the RT60 of a room, its volume, and its total absorption (in sabins). This is given by the equation:

.

.

where  is a number that relates to the speed of sound in the room,

is a number that relates to the speed of sound in the room,  is the volume of the room in m³,

is the volume of the room in m³,  total surface area of room in m²,

total surface area of room in m²,  is the average absorption coefficient of room surfaces, and the product

is the average absorption coefficient of room surfaces, and the product  is the total absorption in sabins.

is the total absorption in sabins.

The total absorption in sabins (and hence reverberation time) generally changes depending on frequency (which is defined by the acoustic properties of the space). The equation does not take into account room shape or losses from the sound travelling through the air (important in larger spaces). Most rooms absorb less sound energy in the lower frequency ranges resulting in longer reverb times at lower frequencies.

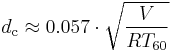

The reverberation time RT60 and the volume V of the room have great influence on the critical distance dc (conditional equation):

where critical distance  is measured in meters, volume

is measured in meters, volume  is measured in m³, and reverberation time

is measured in m³, and reverberation time  is measured in seconds.

is measured in seconds.

Absorption

The absorption coefficient of a material is a number between 0 and 1 which indicates the proportion of sound which is absorbed by the surface compared to the proportion which is reflected back into the room. A large, fully open window would offer no reflection as any sound reaching it would pass straight out and no sound would be reflected. This would have an absorption coefficient of 1. Conversely, a thick, smooth painted concrete ceiling would be the acoustic equivalent of a mirror, and would have an absorption coefficient very close to 0.

Measurement of reverberation time

Historically reverberation time could only be measured using a level recorder (a plotting device which graphs the noise level against time on a ribbon of moving paper). A loud noise is produced, and as the sound dies away the trace on the level recorder will show a distinct slope. Analysis of this slope reveals the measured reverberation time. Some modern digital sound level meters can carry out this analysis automatically.

Currently several methods exist for measuring reverb time. An impulse can be measured by creating a sufficiently loud noise (which must have a defined cut off point). Impulse noise sources such as a blank pistol shot or balloon burst may be used to measure the impulse response of a room.

Alternatively, a random noise signal such as pink noise or white noise may be generated through a loudspeaker, and then turned off. This is known as the interrupted method, and the measured result is known as the interrupted response.

A two port measurement system can also be used to measure noise introduced into a space and compare it to what is subsequently measured in the space. Consider sound reproduced by a loudspeaker into a room. A recording of the sound in the room can be made and compared to what was sent to the loudspeaker. The two signals can be compared mathematically. This two port measurement system utilizes a Fourier transform to mathematically derive the impulse response of the room. From the impulse response, the reverberation time can be calculated. Using a two port system, allows reverberation time to be measured with signals other than loud impulses. Music or recordings of other sound can be used. This allows measurements to be taken in a room after the audience is present.

Reverberation time is usually stated as a decay time and is measured in seconds. There may or may not be any statement of the frequency band used in the measurement. Decay time is the time it takes the signal to diminish 60 dB below the original sound.

Creating reverberation effects

It is often desirable to create a reverberation effect for recorded or live music. A number of systems have been developed to facilitate or simulate reverberation.

Chamber reverberators

The first reverb effects created for recordings used a real physical space as a natural echo chamber. A loudspeaker would play the sound, and then a microphone would pick it up again, including the effects of reverb. Although this is still a common technique, it requires a dedicated soundproofed room, and varying the reverb time is difficult.

Plate reverberators

A plate reverb system uses an electromechanical transducer, similar to the driver in a loudspeaker, to create vibration in a large plate of sheet metal. A pickup captures the vibrations as they bounce across the plate, and the result is output as an audio signal. In the late 1950s, Elektro-Mess-Technik (EMT) introduced the EMT 140;[5] a 600-pound (270 kg) model popular in recording studios, contributing to many hit records such as those recorded by Bill Porter in Nashville's RCA Studio B. Early units had one pickup for mono output, later models featured two pickups for stereo use. The reverb time can be adjusted by a damping pad, made from framed acoustic tiles. The closer the damping pad, the shorter the reverb time. However, the pad never touches the plate. Some units also featured a remote control.

Spring reverberators

A spring reverb system uses a transducer at one end of a spring and a pickup at the other, similar to those used in plate reverbs, to create and capture vibrations within a metal spring. Guitar amplifiers frequently incorporate spring reverbs due to their compact construction and low cost. Spring reverberators were once widely used in semi-professional recording due to their modest cost and small size.

Many musicians have made use of spring reverb units by rocking them back and forth, creating a thundering, crashing sound caused by the springs colliding with each other. The Hammond Organ included an inbuilt spring reverberator, making this a popular effect when used in a rock band.

Digital reverberators

Digital reverberators use various signal processing algorithms in order to create the reverb effect. Since reverberation is essentially caused by a very large number of echoes, simple reverberation algorithms use multiple feedback delay circuits to create a large, decaying series of echoes. More advanced digital reverb generators can simulate the time and frequency domain responses of real rooms (based upon room dimensions, absorption and other properties). In real music halls, the direct sound always arrives at the listener's ear first because it follows the shortest path. Shortly after the direct sound, the reverberant sound arrives. The time between the two is called the "pre-delay."

Convolution reverb

See also

References

- ^ Valente, Michael; Holly Hosford-Dunn, Ross J. Roeser (2008). Audiology. Thieme. pp. 425–426. ISBN 9781588905208.

- ^ Lloyd, Llewelyn Southworth (1970). Music and Sound. Ayer Publishing. pp. 169. ISBN 9780836951882.

- ^ Roth, Leland M. (2007). Understanding Architecture. Westview Press. pp. 104–105. ISBN 9780813390451.

- ^ "So why does reverberation affect speech intelligibility?". MC Squared System Design Group, Inc. http://www.mcsquared.com/y-reverb.htm. Retrieved 2008-12-04.

- ^ Eargle, John M. (2005). Handbook of Recording Engineering (4 ed.). Birkhäuser. p. 233. ISBN 0387284702. http://books.google.com/books?id=00m1SlorUcIC&pg=PA233.

External links

- Reverberation - Hyperphysics

- A database of measured room impulse responses to generate realistic reverberation effects

- Spring Reverb Tanks Explained and Compared

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||