Response amplitude operator

In the field of ship design and design of other floating structures, a response amplitude operator (RAO) is an engineering statistic, or set of such statistics, that are used to determine the likely behaviour of a ship when operating at sea. Known by the acronym of RAO, response amplitude operators are usually obtained from models of proposed ship designs tested in a model basin, or from running specialized CFD computer programs, often both. RAOs are usually calculated for all ship motions and for all wave headings.

Contents |

Usage

RAOs are effectively transfer functions used to determine the effect that a sea state will have upon the motion of a ship through the water, and therefore, for example, whether or not (in the case of cargo vessels) the addition of cargo to the vessel will require measures to be taken to improve stability and prevent the cargo from shifting within the vessel. Generation of extensive RAOs at the design phase allows shipbuilders to determine the modifications to a design that may be required for safety reasons (i.e., to make the design robust and resistant to capsizing or sinking in highly adverse sea conditions) or to improve performance (e.g., improve top speed, fuel consumption, stability in rough seas). RAOs are computed in tandem with the generation of a hydrodynamic database, which is a model of the effects of water pressure upon the ship's hull under a wide variety of flow conditions. Together, the RAOs and hydrodynamic database provide (inasmuch as this is possible within modelling and engineering constraints) certain assurances about the behaviour of a proposed ship design. They also allow the designer to dimension the ship or structure so it will hold up to the most extreme sea states it will likely be subjected to (based on sea state statistics).

RAOs in ship design

Different modelling and design criteria will affect the nature of the 'ideal' RAO curves (as plotted graphically) being sought for a particular ship: for example, an ocean cruise liner will have a considerable emphasis placed upon minimizing accelerations to ensure the comfort of the passengers, while the stability concerns for a naval warship will be concentrated upon making the ship an effective weapons platform.

Methods for calculating

When calculating the response of ships in regular waves it is often possible to neglect the effects of viscosity in certain modes of motion. Fairly accurate results can then be found by using potential theory. The calculations are often divided into two sub-problems:

- Finding the forces on the ship when it is restrained from motion and subjected to regular waves. The forces acting on the body are:

- The Froude–Krylov force, which is the pressure in the undisturbed waves integrated over the wetted surface of the ship.

- The Diffraction forces, which are pressures that occur due to the disturbances in the water because of the ship being present.

- Finding the forces on the ship when it is forced to oscillate in still water conditions. The forces are divided into:

- Added mass forces due to having to accelerate the water along with the ship.

- Damping forces due to the oscillations creating outgoing waves which carry energy away from the ship.

- Restoring forces due to bringing the buoyancy/weight equilibrium out of balance.

In the above "Ship" must be interpreted widely to also include other forms of floating structures. The obvious problem in the above method is the neglection of viscous forces which contribute heavily in modes of motion like surge and roll.

On a computer the above algorithm was first introduced by using strip theory. Today strip theory is still used if the need for fast calculations outweigh the need for precise results and the ship designer knows the limitations of strip theory. The more advanced programs that are used today may not use the exact algorithm outlined above and may also include the effects of viscosity. The insight into the forces that governs the seakeeping behaviour of a ship gained from the above are of course still valid.

Calculating the RAO

The RAO transfer function is only defined when the ship motions can be assumed to be linear. The above forces can then be assembled into an equation of motion:

Where  is the oscillation frequency,

is the oscillation frequency,  is the structural mass and inertia

is the structural mass and inertia  is the added mass (frequency dependent),

is the added mass (frequency dependent),  is the linear damping (frequency dependent),

is the linear damping (frequency dependent),  is the restoring force and

is the restoring force and  is the harmonic excitation force proportional to

is the harmonic excitation force proportional to  and the wave height

and the wave height  .

.

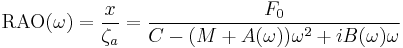

This can be solved for  and the RAO is then:

and the RAO is then:

where  is the linear excitation force complex amplitude per wave height. The RAO is a frequency dependent and complex function (the

is the linear excitation force complex amplitude per wave height. The RAO is a frequency dependent and complex function (the  in the above expression is the imaginary unit). It is common to only consider the absolute value of the RAO if the phase between the excitation and the ship motions are irrelevant.

in the above expression is the imaginary unit). It is common to only consider the absolute value of the RAO if the phase between the excitation and the ship motions are irrelevant.

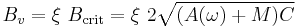

It is common to add a linearised viscous damping term,  to account for the strong non-linearity of the damping force, especially in the roll motion. This term is for simplicity often taken as a fraction of the critical damping,

to account for the strong non-linearity of the damping force, especially in the roll motion. This term is for simplicity often taken as a fraction of the critical damping,  . The expression is then:

. The expression is then:

where:

A good simplification is to use the infinite frequency added mass,  in the above expression to find a frequency independent critical damping value.

in the above expression to find a frequency independent critical damping value.

See also

References

-

- Ultramarine Inc. web page illustrating RAO curves and describing their uses (note: contains content aimed at ship design professionals)

- Faltinsen, O. M. (1990). Sea Loads on Ships and Offshore Structures. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-45870-6.

![\big[ M %2B A(\omega) \big] \ddot x %2B B(\omega) \dot x %2B C x = F(\omega)](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/681100be051a1c6b97f01e00e451994d.png)

![\big[ M %2B A(\omega) \big] \ddot x %2B \big[ B(\omega) %2B B_v \big] \dot x %2B C x = F(\omega)](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/f14fe271fdcfe838c5a8ead1d5f97dee.png)