Regular number

Regular numbers are numbers that evenly divide powers of 60. As an example, 602 = 3600 = 48 × 75, so both 48 and 75 are divisors of a power of 60. Thus, they are also regular numbers.

The numbers that evenly divide the powers of 60 arise in several areas of mathematics and its applications, and have different names coming from these different areas of study.

- In number theory, these numbers are called 5-smooth, because they can be characterized as having only 2, 3, or 5 as prime factors. This is a specific case of the more general k-smooth numbers, i.e., a set of numbers that have no prime factor greater than k.

- In the study of Babylonian mathematics, the divisors of powers of 60 are called regular numbers or regular sexagesimal numbers, and are of great importance due to the sexagesimal number system used by the Babylonians.

- In music theory, regular numbers occur in the ratios of tones in just intonation, also called 5-limit tuning for this reason.

- In computer science, regular numbers are often called Hamming numbers, after Richard Hamming, who proposed the problem of finding computer algorithms for generating these numbers in order.

Contents |

Number theory

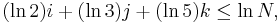

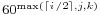

Formally, a regular number is an integer of the form 2i·3j·5k, for nonnegative integers i, j, and k. Such a number is a divisor of  . The regular numbers are also called 5-smooth, indicating that their greatest prime factor is at most 5.

. The regular numbers are also called 5-smooth, indicating that their greatest prime factor is at most 5.

The first few regular numbers are

- 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 12, 15, 16, 18, 20, 24, 25, 27, 30, 32, 36, 40, 45, 48, 50, 54, 60, ... (sequence A051037 in OEIS).

Several other sequences at OEIS have definitions involving 5-smooth numbers.[2]

Although the regular numbers appear dense within the range from 1 to 60, they are quite sparse among the larger integers. A regular number n = 2i·3j·5k is less than or equal to N if and only if the point (i,j,k) belongs to the tetrahedron bounded by the coordinate planes and the plane

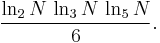

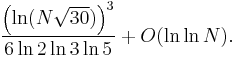

as can be seen by taking logarithms of both sides of the inequality 2i·3j·5k ≤ N. Therefore, the number of regular numbers that are at most N can be estimated as the volume of this tetrahedron, which is

Even more precisely, using big O notation, the number of regular numbers up to N is

A similar formula for the number of 3-smooth numbers up to N is given by Srinivasa Ramanujan in his first letter to G. H. Hardy.[3]

Babylonian mathematics

In the Babylonian sexagesimal notation, the reciprocal of a regular number has a finite representation, thus being easy to divide by. Specifically, if n divides 60k, then the sexagesimal representation of 1/n is just that for 60k/n, shifted by some number of places.

For instance, suppose we wish to divide by the regular number 54 = 2133. 54 is a divisor of 603, and 603/54 = 4000, so dividing by 54 in sexagesimal can be accomplished by multiplying by 4000 and shifting three places. In sexagesimal 4000 = 1×3600 + 6×60 + 40×1, or (as listed by Joyce) 1:6:40. Thus, 1/54, in sexagesimal, is 1/60 + 6/602 + 40/603, also denoted 1:6:40 as Babylonian notational conventions did not specify the power of the starting digit. Conversely 1/4000 = 54/603, so division by 1:6:40 = 4000 can be accomplished by instead multiplying by 54 and shifting three sexagesimal places.

The Babylonians used tables of reciprocals of regular numbers, some of which still survive (Sachs, 1947). These tables existed relatively unchanged throughout Babylonian times.[4]

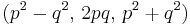

Although the primary reason for preferring regular numbers to other numbers involves the finiteness of their reciprocals, some Babylonian calculations other than reciprocals also involved regular numbers. For instance, tables of regular squares have been found[4] and the broken cuneiform tablet Plimpton 322 has been interpreted by Neugebauer as listing Pythagorean triples  generated by p, q both regular and less than 60.[5]

generated by p, q both regular and less than 60.[5]

Music theory

In music theory, the just intonation of the diatonic scale involves regular numbers: the pitches in a single octave of this scale have frequencies proportional to the numbers in the sequence 24, 27, 30, 32, 36, 40, 45, 48 of nearly-consecutive regular numbers. Thus, for an instrument with this tuning, all pitches are regular-number harmonics of a single fundamental frequency. This scale is called a 5-limit tuning, meaning that the interval between any two pitches can be described as a product 2i3j5k of powers of the prime numbers up to 5, or equivalently as a ratio of regular numbers.

5-limit musical scales other than the familiar diatonic scale of Western music have also been used, both in traditional musics of other cultures and in modern experimental music: Honing & Bod (2005) list 31 different 5-limit scales, drawn from a larger database of musical scales. Each of these 31 scales shares with diatonic just intonation the property that all intervals are ratios of regular numbers. Euler's tonnetz provides a convenient graphical representation of the pitches in any 5-limit tuning, by factoring out the octave relationships (powers of two) so that the remaining values form a planar grid. Some music theorists have stated more generally that regular numbers are fundamental to tonal music itself, and that pitch ratios based on primes larger than 5 cannot be consonant.[6] However the equal temperament of modern pianos is not a 5-limit tuning, and some modern composers have experimented with tunings based on primes larger than five.

In connection with the application of regular numbers to music theory, it is of interest to find pairs of regular numbers that differ by one. There are exactly ten such pairs (x, x+1)[7] and each such pair defines a superparticular ratio (x + 1)/x that is meaningful as a musical interval. These intervals are 2/1 (the octave), 3/2 (the perfect fifth), 4/3 (the perfect fourth), 5/4 (the just major third), 6/5 (the just minor third), 9/8 (the just major tone), 10/9 (the just minor tone), 16/15 (the just diatonic semitone), 25/24 (the just chromatic semitone), and 81/80 (the syntonic comma).

Algorithms

Algorithms for calculating the regular numbers in ascending order were popularized by Edsger Dijkstra. Dijkstra (1981) attributes to Hamming the problem of building the infinite ascending sequence of all 5-smooth numbers; this problem is now known as Hamming's problem, and the numbers so generated are also called the Hamming numbers. Dijkstra's ideas to compute these numbers are the following:

- The sequence of Hamming numbers begins with the number 1.

- The remaining values in the sequence are of the form 2h, 3h, and 5h, where h is any Hamming number.

- Therefore, the sequence H may be generated by outputting the value 1, and then merging the sequences 2H, 3H, and 5H.

This algorithm is often used to demonstrate the power of a lazy functional programming language, because (implicitly) concurrent efficient implementations, using a constant number of arithmetic operations per generated value, are easily constructed as described above. Similarly efficient strict functional or imperative sequential implementations are also possible whereas explicitly concurrent generative solutions might be non-trivial.[8]

In the Python programming language, lazy functional code for generating regular numbers is used as one of the built-in tests for correctness of the language's implementation.[9]

A related problem, discussed by Knuth (1972), is to list all k-digit sexagesimal numbers in ascending order, as was done (for k = 6) by Inakibit-Anu, the Seleucid-era scribe of tablet AO6456. In algorithmic terms, this is equivalent to generating (in order) the subsequence of the infinite sequence of regular numbers, ranging from 60k to 60k + 1. See Gingerich (1965) for an early description of computer code that generates these numbers out of order and then sorts them; Knuth describes an ad-hoc algorithm, which he attributes to Bruins (1970), for generating the six-digit numbers more quickly but that does not generalize in a straightforward way to larger values of k. Eppstein (2007) describes an algorithm for computing tables of this type in linear time for arbitrary values of k.

Other applications

Heninger, Rains & Sloane (2005) show that, when n is a regular number and is divisible by 8, the generating function of an n-dimensional extremal even unimodular lattice is an nth power of a polynomial.

As with other classes of smooth numbers, regular numbers are important as problem sizes in computer programs for performing the fast Fourier transform, a technique for analyzing the dominant frequencies of signals in time-varying data. For instance, the method of Temperton (1992) requires that the transform length be a regular number.

Book VIII of Plato's Republic involves an allegory of marriage centered around the highly regular number 604 = 12,960,000 and its divisors. Later scholars have invoked both Babylonian mathematics and music theory in an attempt to explain this passage.[10]

Notes

- ^ Inspired by similar diagrams by Erkki Kurenniemi in "Chords, scales, and divisor lattices".

- ^ OEIS search for sequences involving 5-smoothness.

- ^ Berndt, Bruce C.; Rankin, Robert Alexander, eds. (1995), Ramanujan: letters and commentary, History of mathematics, 9, American Mathematical Society, p. 23, ISBN 9780821804704.

- ^ a b Aaboe (1965).

- ^ See Conway & Guy (1996) for a popular treatment of this interpretation. Plimpton 322 has other interpretations, for which see its article, but all involve regular numbers.

- ^ Asmussen (2001), for instance, states that "within any piece of tonal music" all intervals must be ratios of regular numbers, echoing similar statements by much earlier writers such as Habens (1889). In the modern music theory literature this assertion is often attributed to Longuet-Higgins (1962), who used a graphical arrangement closely related to the tonnetz to organize 5-limit pitches.

- ^ Halsey & Hewitt (1972) note that this follows from Størmer's theorem (Størmer 1897), and provide a proof for this case; see also Silver (1971).

- ^ See, e.g., Hemmendinger (1988) or Yuen (1992).

- ^ Function m235 in test_generators.py.

- ^ Barton (1908); McClain (1974).

References

- Aaboe, Asger (1965), "Some Seleucid mathematical tables (extended reciprocals and squares of regular numbers)", Journal of Cuneiform Studies (The American Schools of Oriental Research) 19 (3): 79–86, doi:10.2307/1359089, JSTOR 1359089, MR0191779.

- Asmussen, Robert (2001), Periodicity of sinusoidal frequencies as a basis for the analysis of Baroque and Classical harmony: a computer based study, Ph.D. thesis, Univ. of Leeds, http://www.terraworld.net/c-jasmussen/thesis_asmussen.pdf.

- Barton, George A. (1908), "On the Babylonian origin of Plato's nuptial number", Journal of the American Oriental Society (American Oriental Society) 29: 210–219, doi:10.2307/592627, JSTOR 592627.

- Bruins, E. M. (1970), "La construction de la grande table le valeurs réciproques AO 6456", in Finet, André, Actes de la XVIIe Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, Comité belge de recherches en Mésopotamie, pp. 99–115.

- Conway, John H.; Guy, Richard K. (1996), The Book of Numbers, Copernicus, pp. 172–176, ISBN 0-387-97993-X.

- Dijkstra, Edsger W. (1981), Hamming's exercise in SASL, Report EWD792. Originally a privately-circulated handwitten note, http://www.cs.utexas.edu/users/EWD/ewd07xx/EWD792.PDF.

- Eppstein, David (2007), The range-restricted Hamming problem, http://11011110.livejournal.com/95519.html.

- Gingerich, Owen (1965), "Eleven-digit regular sexagesimals and their reciprocals", Transactions of the American Philosophical Society (American Philosophical Society) 55 (8): 3–38, doi:10.2307/1006080, JSTOR 1006080.

- Habens, Rev. W. J. (1889), "On the musical scale", Proceedings of the Musical Association (Royal Musical Association) 16: 16th Session, p. 1, JSTOR 765355.

- Halsey, G. D.; Hewitt, Edwin (1972), "More on the superparticular ratios in music", American Mathematical Monthly (Mathematical Association of America) 79 (10): 1096–1100, doi:10.2307/2317424, JSTOR 2317424, MR0313189.

- Hemmendinger, David (1988), "The "Hamming problem" in Prolog", ACM SIGPLAN Notices 23 (4): 81–86, doi:10.1145/44326.44335.

- Heninger, Nadia; Rains, E. M.; Sloane, N. J. A. (2005). "On the integrality of nth roots of generating functions". arXiv:math.NT/0509316..

- Honingh, Aline; Bod, Rens (2005), "Convexity and the well-formedness of musical objects", Journal of New Music Research 34 (3): 293–303, doi:10.1080/09298210500280612.

- Knuth, D. E. (1972), "Ancient Babylonian algorithms", Communications of the ACM 15 (7): 671–677, doi:10.1145/361454.361514. Errata in CACM 19(2), 1976. Reprinted with a brief addendum in Selected Papers on Computer Science, CSLI Lecture Notes 59, Cambridge Univ. Press, 1996, pp. 185–203.

- Longuet-Higgins, H. C. (1962), "Letter to a musical friend", Music Review (August): 244–248.

- McClain, Ernest G.; Plato, (1974), "Musical "Marriages" in Plato's "Republic"", Journal of Music Theory (Duke University Press) 18 (2): 242–272, doi:10.2307/843638, JSTOR 843638.

- Sachs, A. J. (1947), "Babylonian mathematical texts. I. Reciprocals of regular sexagesimal numbers", Journal of Cuneiform Studies (The American Schools of Oriental Research) 1 (3): 219–240, doi:10.2307/1359434, JSTOR 1359434, MR0022180.

- Silver, A. L. Leigh (1971), "Musimatics or the nun's fiddle", American Mathematical Monthly (Mathematical Association of America) 78 (4): 351–357, doi:10.2307/2316896, JSTOR 2316896.

- Størmer, Carl (1897), "Quelques théorèmes sur l'équation de Pell x2 - Dy2 = ±1 et leurs applications", Skrifter Videnskabs-selskabet (Christiania), Mat.-Naturv. Kl. I (2).

- Temperton, Clive (1992), "A generalized prime factor FFT algorithm for any N = 2p3q5r", SIAM Journal on Scientific and Statistical Computing 13 (3): 676–686, doi:10.1137/0913039.

- Yuen, C. K. (1992), "Hamming numbers, lazy evaluation, and eager disposal", ACM SIGPLAN Notices 27 (8): 71–75, doi:10.1145/142137.142151.

External links

- Table of reciprocals of regular numbers up to 3600 from the web site of Professor David E. Joyce, Clark University

|

||||||||||||||||||||||