Real number

In mathematics, a real number is a value that represents a quantity along a continuum, such as -5 (an integer), 4/3 (a rational number that is not an integer), 8.6 (a rational number given by a finite decimal representation), √2 (the square root of two, an algebraic number that is not rational) and π (3.1415926535..., a transcendental number). Real numbers can be thought of as points on an infinitely long line called the number line or real line, where the points corresponding to integers are equally spaced. Any real number can be determined by a possibly infinite decimal representation (such as that of π above), where each consecutive digit ar at rank r indicates the addition of ar 10-r to the decimal truncated at rank r-1. The real line can be thought of as a part of the complex plane, and correspondingly, complex numbers include real numbers as a special case.

These descriptions of the real numbers are not sufficiently rigorous by the modern standards of pure mathematics. The discovery of a suitably rigorous definition of the real numbers — indeed, the realization that a better definition was needed — was one of the most important developments of 19th century mathematics. The currently standard axiomatic definition is that real numbers form the unique complete totally ordered field (R,+,·,<), up to isomorphism,[1] whereas popular constructive definitions of real numbers include declaring them as equivalence classes of Cauchy sequences of rational numbers, Dedekind cuts, or certain infinite "decimal representations", together with precise interpretations for the arithmetic operations and the order relation. These definitions are equivalent in the realm of classical mathematics.

Contents |

Basic properties

A real number may be either rational or irrational; either algebraic or transcendental; and either positive, negative, or zero. Real numbers are used to measure continuous quantities. They may in theory be expressed by decimal representations that have an infinite sequence of digits to the right of the decimal point; these are often represented in the same form as 324.823122147… The ellipsis (three dots) indicate that there would still be more digits to come.

More formally, real numbers have the two basic properties of being an ordered field, and having the least upper bound property. The first says that real numbers comprise a field, with addition and multiplication as well as division by nonzero numbers, which can be totally ordered on a number line in a way compatible with addition and multiplication. The second says that if a nonempty set of real numbers has an upper bound, then it has a least upper bound. The second condition distinguishes the real numbers from the rational numbers: for example, the set of rational numbers whose square is less than 2 is a set with an upper bound (e.g. 1.5) but no least upper bound: hence the rational numbers do not satisfy the least upper bound property.

In physics

In the physical sciences, most physical constants such as the universal gravitational constant, and physical variables, such as position, mass, speed, and electric charge, are modeled using real numbers. In fact, the fundamental physical theories such as classical mechanics, electromagnetism, quantum mechanics, general relativity and the standard model are described using mathematical structures, typically smooth manifolds or Hilbert spaces, that are based on the real numbers although actual measurements of physical quantities are of finite accuracy and precision.

In some recent developments of theoretical physics stemming from the holographic principle, the Universe is seen fundamentally as an information store, essentially zeroes and ones, organized in much less geometrical fashion and manifesting itself as space-time and particle fields only on a more superficial level. This approach removes the real number system from its foundational role in physics and even prohibits the existence of infinite precision real numbers in the physical universe by considerations based on the Bekenstein bound.[2]

In computation

Computer arithmetic cannot directly operate on real numbers, but only on a finite subset of rational numbers, limited by the number of bits used to store them, whether as floating-point numbers or arbitrary precision numbers. However, computer algebra systems can operate on irrational quantities exactly by manipulating formulas for them (such as  ,

,  , or

, or ) rather than their rational or decimal approximation;[3] however, it is not in general possible to determine whether two such expressions are equal (the Constant problem).

) rather than their rational or decimal approximation;[3] however, it is not in general possible to determine whether two such expressions are equal (the Constant problem).

A real number is said to be computable if there exists an algorithm that yields its digits. Because there are only countably many algorithms,[4] but an uncountable number of reals, almost all real numbers fail to be computable. Some constructivists accept the existence of only those reals that are computable. The set of definable numbers is broader, but still only countable.

Notation

Mathematicians use the symbol R (or alternatively,  , the letter "R" in blackboard bold, Unicode ℝ – U+211D) to represent the set of all real numbers (as this set is naturally endowed with a structure of field, the expression field of the real numbers is more frequently used than set of all real numbers). The notation Rn refers to the Cartesian product of n copies of R, which is an n-dimensional vector space over the field of the real numbers; this vector space may be identified to the n-dimensional space of Euclidean geometry as soon as a coordinate system has been chosen in the latter. For example, a value from R3 consists of three real numbers and specifies the coordinates of a point in 3-dimensional space.

, the letter "R" in blackboard bold, Unicode ℝ – U+211D) to represent the set of all real numbers (as this set is naturally endowed with a structure of field, the expression field of the real numbers is more frequently used than set of all real numbers). The notation Rn refers to the Cartesian product of n copies of R, which is an n-dimensional vector space over the field of the real numbers; this vector space may be identified to the n-dimensional space of Euclidean geometry as soon as a coordinate system has been chosen in the latter. For example, a value from R3 consists of three real numbers and specifies the coordinates of a point in 3-dimensional space.

In mathematics, real is used as an adjective, meaning that the underlying field is the field of the real numbers (or the real field). For example real matrix, real polynomial and real Lie algebra. As a substantive, the term is used almost strictly in reference to the real numbers themselves (e.g., The "set of all reals").

History

Vulgar fractions had been used by the Egyptians around 1000 BC; the Vedic "Sulba Sutras" ("The rules of chords") in, ca. 600 BC, include what may be the first 'use' of irrational numbers. The concept of irrationality was implicitly accepted by early Indian mathematicians since Manava (c. 750–690 BC), who were aware that the square roots of certain numbers such as 2 and 61 could not be exactly determined.[5] Around 500 BC, the Greek mathematicians led by Pythagoras realized the need for irrational numbers, in particular the irrationality of the square root of 2.

The Middle Ages saw the acceptance of zero, negative, integral and fractional numbers, first by Indian and Chinese mathematicians, and then by Arabic mathematicians, who were also the first to treat irrational numbers as algebraic objects,[6] which was made possible by the development of algebra. Arabic mathematicians merged the concepts of "number" and "magnitude" into a more general idea of real numbers.[7] The Egyptian mathematician Abū Kāmil Shujā ibn Aslam (c. 850–930) was the first to accept irrational numbers as solutions to quadratic equations or as coefficients in an equation, often in the form of square roots, cube roots and fourth roots.[8]

In the 16th century, Simon Stevin created the basis for modern decimal notation, and insisted that there is no difference between rational and irrational numbers in this regard.

In the 17th century, Descartes introduced the term "real" to describe roots of a polynomial, distinguishing them from "imaginary" ones.

In the 18th and 19th centuries there was much work on irrational and transcendental numbers. Johann Heinrich Lambert (1761) gave the first flawed proof that π cannot be rational; Adrien-Marie Legendre (1794) completed the proof, and showed that π is not the square root of a rational number. Paolo Ruffini (1799) and Niels Henrik Abel (1842) both constructed proofs of Abel–Ruffini theorem: that the general quintic or higher equations cannot be solved by a general formula involving only arithmetical operations and roots.

Évariste Galois (1832) developed techniques for determining whether a given equation could be solved by radicals, which gave rise to the field of Galois theory. Joseph Liouville (1840) showed that neither e nor e2 can be a root of an integer quadratic equation, and then established existence of transcendental numbers, the proof being subsequently displaced by Georg Cantor (1873). Charles Hermite (1873) first proved that e is transcendental, and Ferdinand von Lindemann (1882), showed that π is transcendental. Lindemann's proof was much simplified by Weierstrass (1885), still further by David Hilbert (1893), and has finally been made elementary by Adolf Hurwitz and Paul Gordan.

The development of calculus in the 18th century used the entire set of real numbers without having defined them cleanly. The first rigorous definition was given by Georg Cantor in 1871. In 1874 he showed that the set of all real numbers is uncountably infinite but the set of all algebraic numbers is countably infinite. Contrary to widely held beliefs, his first method was not his famous diagonal argument, which he published in 1891. See Cantor's first uncountability proof.

Definition

The real number system  can be defined axiomatically up to an isomorphism, which is described below. There are also many ways to construct "the" real number system, for example, starting from natural numbers, then defining rational numbers algebraically, and finally defining real numbers as equivalence classes of their Cauchy sequences or as Dedekind cuts, which are certain subsets of rational numbers. Another possibility is to start from some rigorous axiomatization of Euclidean geometry (Hilbert, Tarski etc.) and then define the real number system geometrically. From the structuralist point of view all these constructions are on equal footing.

can be defined axiomatically up to an isomorphism, which is described below. There are also many ways to construct "the" real number system, for example, starting from natural numbers, then defining rational numbers algebraically, and finally defining real numbers as equivalence classes of their Cauchy sequences or as Dedekind cuts, which are certain subsets of rational numbers. Another possibility is to start from some rigorous axiomatization of Euclidean geometry (Hilbert, Tarski etc.) and then define the real number system geometrically. From the structuralist point of view all these constructions are on equal footing.

Axiomatic approach

Let R denote the set of all real numbers. Then:

- The set R is a field, meaning that addition and multiplication are defined and have the usual properties.

- The field R is ordered, meaning that there is a total order ≥ such that, for all real numbers x, y and z:

- if x ≥ y then x + z ≥ y + z;

- if x ≥ 0 and y ≥ 0 then xy ≥ 0.

- The order is Dedekind-complete; that is, every non-empty subset S of R with an upper bound in R has a least upper bound (also called supremum) in R.

The last property is what differentiates the reals from the rationals. For example, the set of rationals with square less than 2 has a rational upper bound (e.g., 1.5) but no rational least upper bound, because the square root of 2 is not rational.

The real numbers are uniquely specified by the above properties. More precisely, given any two Dedekind-complete ordered fields R1 and R2, there exists a unique field isomorphism from R1 to R2, allowing us to think of them as essentially the same mathematical object.

For another axiomatization of R, see Tarski's axiomatization of the reals.

Construction from the rational numbers

The real numbers can be constructed as a completion of the rational numbers in such a way that a sequence defined by a decimal or binary expansion like {3, 3.1, 3.14, 3.141, 3.1415,...} converges to a unique real number. For details and other constructions of real numbers, see construction of the real numbers.

Properties

Completeness

A main reason for using real numbers is that the reals contain all limits. More precisely, every sequence of real numbers having the property that consecutive terms of the sequence become arbitrarily close to each other necessarily has the property that after some term in the sequence the remaining terms are arbitrarily close to some specific real number. In mathematical terminology, this means that the reals are complete (in the sense of metric spaces or uniform spaces, which is a different sense than the Dedekind completeness of the order in the previous section). This is formally defined in the following way:

A sequence (xn) of real numbers is called a Cauchy sequence if for any ε > 0 there exists an integer N (possibly depending on ε) such that the distance |xn − xm| is less than ε for all n and m that are both greater than N. In other words, a sequence is a Cauchy sequence if its elements xn eventually come and remain arbitrarily close to each other.

A sequence (xn) converges to the limit x if for any ε > 0 there exists an integer N (possibly depending on ε) such that the distance |xn − x| is less than ε provided that n is greater than N. In other words, a sequence has limit x if its elements eventually come and remain arbitrarily close to x.

Notice that every convergent sequence is a Cauchy sequence. The converse is also true:

- Every Cauchy sequence of real numbers is convergent to a real number.

That is, the reals are complete.

Note that the rationals are not complete. For example, the sequence (1, 1.4, 1.41, 1.414, 1.4142, 1.41421, ...), where each term adds a digit of the decimal expansion of the positive square root of 2, is Cauchy but it does not converge to a rational number. (In the real numbers, in contrast, it converges to the positive square root of 2.)

The existence of limits of Cauchy sequences is what makes calculus work and is of great practical use. The standard numerical test to determine if a sequence has a limit is to test if it is a Cauchy sequence, as the limit is typically not known in advance.

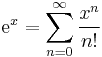

For example, the standard series of the exponential function

converges to a real number because for every x the sums

can be made arbitrarily small by choosing N sufficiently large. This proves that the sequence is Cauchy, so we know that the sequence converges even if the limit is not known in advance.

"The complete ordered field"

The real numbers are often described as "the complete ordered field", a phrase that can be interpreted in several ways.

First, an order can be lattice-complete. It is easy to see that no ordered field can be lattice-complete, because it can have no largest element (given any element z, z + 1 is larger), so this is not the sense that is meant.

Additionally, an order can be Dedekind-complete, as defined in the section Axioms. The uniqueness result at the end of that section justifies using the word "the" in the phrase "complete ordered field" when this is the sense of "complete" that is meant. This sense of completeness is most closely related to the construction of the reals from Dedekind cuts, since that construction starts from an ordered field (the rationals) and then forms the Dedekind-completion of it in a standard way.

These two notions of completeness ignore the field structure. However, an ordered group (in this case, the additive group of the field) defines a uniform structure, and uniform structures have a notion of completeness (topology); the description in the section Completeness above is a special case. (We refer to the notion of completeness in uniform spaces rather than the related and better known notion for metric spaces, since the definition of metric space relies on already having a characterisation of the real numbers.) It is not true that R is the only uniformly complete ordered field, but it is the only uniformly complete Archimedean field, and indeed one often hears the phrase "complete Archimedean field" instead of "complete ordered field". Since it can be proved that any uniformly complete Archimedean field must also be Dedekind-complete (and vice versa, of course), this justifies using "the" in the phrase "the complete Archimedean field". This sense of completeness is most closely related to the construction of the reals from Cauchy sequences (the construction carried out in full in this article), since it starts with an Archimedean field (the rationals) and forms the uniform completion of it in a standard way.

But the original use of the phrase "complete Archimedean field" was by David Hilbert, who meant still something else by it. He meant that the real numbers form the largest Archimedean field in the sense that every other Archimedean field is a subfield of R. Thus R is "complete" in the sense that nothing further can be added to it without making it no longer an Archimedean field. This sense of completeness is most closely related to the construction of the reals from surreal numbers, since that construction starts with a proper class that contains every ordered field (the surreals) and then selects from it the largest Archimedean subfield.

Advanced properties

The reals are uncountable, that is, there are strictly more real numbers than natural numbers, even though both sets are infinite. In fact, the cardinality of the reals equals that of the set of subsets (i.e., the power set) of the natural numbers, and Cantor's diagonal argument states that the latter set's cardinality is strictly bigger than the cardinality of N. Since only a countable set of real numbers can be algebraic, almost all real numbers are transcendental. The non-existence of a subset of the reals with cardinality strictly between that of the integers and the reals is known as the continuum hypothesis. The continuum hypothesis can neither be proved nor be disproved; it is independent from the axioms of set theory.

As a topological space, the real numbers are separable. This is because the set of rationals, which is countable, is dense in the real numbers. The irrational numbers are also dense in the real numbers, however they are uncountable and have the same cardinality as the reals.

The real numbers form a metric space: the distance between x and y is defined to be the absolute value |x − y|. By virtue of being a totally ordered set, they also carry an order topology; the topology arising from the metric and the one arising from the order are identical, but yield different presentations for the topology – in the order topology as intervals, in the metric topology as epsilon-balls. The Dedekind cuts construction uses the order topology presentation, while the Cauchy sequences construction uses the metric topology presentation. The reals are a contractible (hence connected and simply connected), separable and complete metric space of Hausdorff dimension 1. The real numbers are locally compact but not compact. There are various properties that uniquely specify them; for instance, all unbounded, connected, and separable order topologies are necessarily homeomorphic to the reals.

Every nonnegative real number has a square root in R, although no negative number does. This shows that the order on R is determined by its algebraic structure. Also, every polynomial of odd degree admits at least one real root: these two properties make R the premier example of a real closed field. Proving this is the first half of one proof of the fundamental theorem of algebra.

The reals carry a canonical measure, the Lebesgue measure, which is the Haar measure on their structure as a topological group normalised such that the unit interval [0,1] has measure 1.

The supremum axiom of the reals refers to subsets of the reals and is therefore a second-order logical statement. It is not possible to characterize the reals with first-order logic alone: the Löwenheim–Skolem theorem implies that there exists a countable dense subset of the real numbers satisfying exactly the same sentences in first order logic as the real numbers themselves. The set of hyperreal numbers satisfies the same first order sentences as R. Ordered fields that satisfy the same first-order sentences as R are called nonstandard models of R. This is what makes nonstandard analysis work; by proving a first-order statement in some nonstandard model (which may be easier than proving it in R), we know that the same statement must also be true of R.

Generalizations and extensions

The real numbers can be generalized and extended in several different directions:

- The complex numbers contain solutions to all polynomial equations and hence are an algebraically closed field unlike the real numbers. However, the complex numbers are not an ordered field.

- The affinely extended real number system adds two elements +∞ and −∞. It is a compact space. It is no longer a field, not even an additive group, but it still has a total order; moreover, it is a complete lattice.

- The real projective line adds only one value ∞. It is also a compact space. Again, it is no longer a field, not even an additive group. However, it allows division of a non-zero element by zero. It is not ordered anymore.

- The long real line pastes together ℵ1* + ℵ1 copies of the real line plus a single point (here ℵ1* denotes the reversed ordering of ℵ1) to create an ordered set that is "locally" identical to the real numbers, but somehow longer; for instance, there is an order-preserving embedding of ℵ1 in the long real line but not in the real numbers. The long real line is the largest ordered set that is complete and locally Archimedean. As with the previous two examples, this set is no longer a field or additive group.

- Ordered fields extending the reals are the hyperreal numbers and the surreal numbers; both of them contain infinitesimal and infinitely large numbers and thus are not Archimedean.

- Self-adjoint operators on a Hilbert space (for example, self-adjoint square complex matrices) generalize the reals in many respects: they can be ordered (though not totally ordered), they are complete, all their eigenvalues are real and they form a real associative algebra. Positive-definite operators correspond to the positive reals and normal operators correspond to the complex numbers.

"Reals" in set theory

In set theory, specifically descriptive set theory, the Baire space is used as a surrogate for the real numbers since the latter have some topological properties (connectedness) that are a technical inconvenience. Elements of Baire space are referred to as "reals".

Real numbers and logic

The real numbers are most often formalized using the Zermelo-Fraenkel axiomatization of set theory, but some mathematicians study the real numbers with other logical foundations of mathematics. In particular, the real numbers are also studied in reverse mathematics and in constructive mathematics.[9]

Abraham Robinson's theory of nonstandard or hyperreal numbers extends the set of the real numbers by infinitesimal numbers, which allows the building of infinitesimal calculus in a way which is closer to the usual intuition of the notion of limit. Edward Nelson's internal set theory is a non Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory which allows to consider the non standard real numbers as elements of the set of the reals (and not of an extension of it as in Robinson's theory).

The continuum hypothesis posits that the cardinality of the set of the real numbers is  , i.e. the smallest infinite cardinal number after

, i.e. the smallest infinite cardinal number after  , the cardinality of the integers. Paul Cohen has proved in 1963 that it is an axiom which is independent of the other axioms of set theory; that is, one may choose either the continuum hypothesis or its negation as an axiom of set theory, without making it contradictory.

, the cardinality of the integers. Paul Cohen has proved in 1963 that it is an axiom which is independent of the other axioms of set theory; that is, one may choose either the continuum hypothesis or its negation as an axiom of set theory, without making it contradictory.

See also

Notes

- ^ More precisely, given two complete totally ordered fields, there is a unique isomorphism between them. This implies that the identity is the unique field automorphism of the reals which is compatible with the ordering.

- ^ Scott Aaronson, NP-complete Problems and Physical Reality, ACM SIGACT News, Vol. 36, No. 1. (March 2005), pp. 30–52.

- ^ Cohen, Joel S. (2002), Computer algebra and symbolic computation: elementary algorithms, 1, A K Peters, Ltd., p. 32, ISBN 9781568811581

- ^ James L. Hein, Discrete Structures, Logic, and Computability, 3rd edition (Jones and Bartlett Publishers: Sudbury, MA), section 14.1.1 (2010).

- ^ T. K. Puttaswamy, "The Accomplishments of Ancient Indian Mathematicians", pp. 410–1, in Selin, Helaine; D'Ambrosio, Ubiratan (2000), Mathematics Across Cultures: The History of Non-western Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 1402002602

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Arabic mathematics: forgotten brilliance?", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/HistTopics/Arabic_mathematics.html.

- ^ Matvievskaya, Galina (1987), "The Theory of Quadratic Irrationals in Medieval Oriental Mathematics", Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 500: 253–277 [254], doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb37206.x

- ^ Jacques Sesiano, "Islamic mathematics", p. 148, in Selin, Helaine; D'Ambrosio, Ubiratan (2000), Mathematics Across Cultures: The History of Non-western Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 1402002602

- ^ Bishop, Errett; Bridges, Douglas (1985), Constructive analysis, Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften [Fundamental Principles of Mathematical Sciences], 279, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-15066-4, chapter 2.

References

- Georg Cantor, 1874, "Über eine Eigenschaft des Inbegriffes aller reellen algebraischen Zahlen", Journal für die Reine und Angewandte Mathematik, volume 77, pages 258–262.

- Robert Katz, 1964, Axiomatic Analysis, D. C. Heath and Company.

- Edmund Landau, 2001, ISBN 0-8218-2693-X, Foundations of Analysis, American Mathematical Society.

- Howie, John M., Real Analysis, Springer, 2005, ISBN 1-85233-314-6

External links

- The real numbers: Pythagoras to Stevin

- The real numbers: Stevin to Hilbert

- The real numbers: Attempts to understand

- What are the "real numbers," really?

|

|||||||||||

)

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

)