Rational root theorem

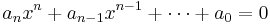

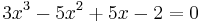

In algebra, the rational root theorem (or rational root test) states a constraint on rational solutions (or roots) of the polynomial equation

with integer coefficients.

If a0 and an are nonzero, then each rational solution x, when written as a fraction x = p/q in lowest terms (i.e., the greatest common divisor of p and q is 1), satisfies

- p is an integer factor of the constant term a0, and

- q is an integer factor of the leading coefficient an.

Thus, a list of possible rational roots of the equation can be derived using the formula  .

.

The rational root theorem is a special case (for a single linear factor) of Gauss's lemma on the factorization of polynomials. The integral root theorem is a special case of the rational root theorem if the leading coefficient an = 1.

Contents |

Proofs

An elementary proof

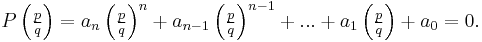

Let P(x) = anxn + an-1xn-1 + ... + a1x + a0 for some a0, ..., an ∈ Z, and suppose P(p/q) = 0 for some coprime p, q ∈ Z:

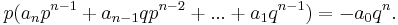

If we shift the constant term to the right hand side and multiply by qn, we get

We see that p times the integer quantity in parentheses equals -a0qn, so p divides a0qn. But p is coprime to q and therefore to qn, so by (the generalized form of) Euclid's lemma it must divide the remaining factor a0 of the product.

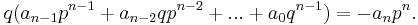

If we instead shift the leading term to the right hand side and multiply by qn, we get

And for similar reasons, we can conclude that q divides an.[1]

Proof using Gauss's lemma

Should there be a nontrivial factor dividing all the coefficients of the polynomial, then one can divide by the greatest common divisor of the coefficients so as to obtain a primitive polynomial in the sense of Gauss's lemma; this does not alter the set of rational roots and only strengthens the divisibility conditions. That lemma says that if the polynomial factors in ℚ[X], then it also factors in ℤ[X] as a product of primitive polynomials. Now any rational root p/q corresponds to a factor of degree 1 in ℚ[X] of the polynomial, and its primitive representative is then qx − p, assuming that p and q are coprime. But any multiple in ℤ[X] of qx − p has leading term divisible by q and constant term divisible by p, which proves the statement. This argument shows that more generally, any irreducible factor of P can be supposed to have integer coefficients, and leading and constant coefficients dividing the corresponding coefficients of P.

Example

For example, every rational solution of the equation

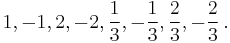

must be among the numbers symbolically indicated by

- ±

which gives the list of possible answers:

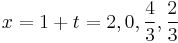

These root candidates can be tested using the Horner scheme (for instance). In this particular case there is exactly one rational root. If a root candidate does not satisfy the equation, it can be used to shorten the list of remaining candidates. For example, x = 1 does not satisfy the equation as the left hand side equals 1. This means that substituting x = 1 + t yields a polynomial in t with constant term 1, while the coefficient of t3 remains the same as the coefficient of x3. Applying the rational root theorem thus yields the following possible roots for t:

Therefore,

Root candidates that do not occur on both lists are ruled out. The list of rational root candidates has thus shrunk to just x = 2 and x = 2/3.

If a root r1 is found, the Horner scheme will also yield a polynomial of degree n − 1 whose roots, together with r1, are exactly the roots of the original polynomial. It may also be the case that none of the candidates is a solution; in this case the equation has no rational solution. If the equation lacks a constant term a0, then 0 is one of the rational roots of the equation.

See also

Notes

References

- Charles D. Miller, Margaret L. Lial, David I. Schneider: Fundamentals of College Algebra. Scott & Foresman/Little & Brown Higher Education, 3rd edition 1990, ISBN 0-673-38638-4, pp. 216-221

- Phillip S. Jones, Jack D. Bedient: The historical roots of elementary mathematics. Dover Courier Publications 1998, ISBN 0486255638, pp. 116-117 (online copy at Google Books)

- Ron Larson: Calculus: An Applied Approach. Cengage Learning 2007, ISBN 9780618958252, pp. 23-24 (online copy at Google Books)

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Rational Zero Theorem" from MathWorld.

- RationalRootTheorem at PlanetMath

- Another proof that nth roots of integers are irrational, except for perfect nth powers by Scott E. Brodie

- The Rational Roots Test at purplemath.com