Rate function

In mathematics — specifically, in large deviations theory — a rate function is a function used to quantify the probabilities of rare events. It is required to have several "nice" properties which assist in the formulation of the large deviation principle. In some sense, the large deviation principle is an analogue of weak convergence of probability measures, but one which takes account of how well the rare events behave.

A rate function is also called a Cramér function, after the Swedish statistician Harald Cramér.

Contents |

Definitions

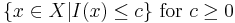

An extended real-valued function I : X → [0, +∞] defined on a Hausdorff topological space X is said to be a rate function if it is not identically +∞ and is lower semi-continuous, i.e. all the sub-level sets

are closed in X. If, furthermore, they are compact, then I is said to be a good rate function.

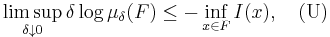

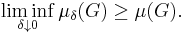

A family of probability measures (μδ)δ>0 on X is said to satisfy the large deviation principle with rate function I : X → [0, +∞) (and rate 1 ⁄ δ) if, for every closed set F ⊆ X and every open set G ⊆ X,

If the upper bound (U) holds only for compact (instead of closed) sets F, then (μδ)δ>0 is said to satisfy the weak large deviation principle (with rate 1 ⁄ δ and weak rate function I).

Remarks

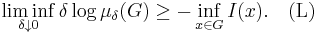

The role of the open and closed sets in the large deviation principle is similar to their role in the weak convergence of probability measures: recall that (μδ)δ>0 is said to converge weakly to μ if, for every closed set F ⊆ X and every open set G ⊆ X,

There is some variation in the nomenclature used in the literature: for example, den Hollander (2000) uses simply "rate function" where this article — following Dembo & Zeitouni (1998) — uses "good rate function", and "weak rate function" where this article uses "rate function". Fortunately, regardless of the nomenclature used for rate functions, examination of whether the upper bound inequality (U) is supposed to hold for closed or compact sets tells one whether the large deviation principle in use is strong or weak.

Properties

Uniqueness

A natural question to ask, given the somewhat abstract setting of the general framework above, is whether the rate function is unique. This turns out to be the case: given a sequence of probability measures (μδ)δ>0 on X satisfying the large deviation principle for two rate functions I and J, it follows that I(x) = J(x) for all x ∈ X.

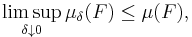

Exponential tightness

It is possible to convert a weak large deviation principle into a strong one if the measures converge sufficiently quickly. If the upper bound holds for compact sets F and the sequence of measures (μδ)δ>0 is exponentially tight, then the upper bound also holds for closed sets F. In other words, exponential tightness enables one to convert a weak large deviation principle into a strong one.

Continuity

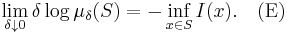

Naïvely, one might try to replace the two inequalities (U) and (L) by the single requirement that, for all Borel sets S ⊆ X,

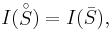

Unfortunately, the equality (E) is far too restrictive, since many interesting examples satisfy (U) and (L) but not (E). For example, the measure μδ might be non-atomic for all δ, so the equality (E) could hold for S = {x} only if I were identically +∞, which is not permitted in the definition. However, the inequalities (U) and (L) do imply the equality (E) for so-called I-continuous sets S ⊆ X, those for which

where  and

and  denote the interior and closure of S in X respectively. In many examples, many sets/events of interest are I-continuous. For example, if I is a continuous function, then all sets S such that

denote the interior and closure of S in X respectively. In many examples, many sets/events of interest are I-continuous. For example, if I is a continuous function, then all sets S such that

are I-continuous; all open sets, for example, satisfy this containment.

Transformation of large deviation principles

Given a large deviation principle on one space, it is often of interest to be able to construct a large deviation principle on another space. There are several results in this area:

- the contraction principle tells one how a large deviation principle on one space "pushes forward" to a large deviation principle on another space via a continuous function;

- the Dawson-Gärtner theorem tells one how a sequence of large deviation principles on a sequence of spaces passes to the projective limit.

- the tilted large deviation principle gives a large deviation principle for integrals of exponential functionals.

- exponentially equivalent measures have the same large deviation principles.

References

- Dembo, Amir; Zeitouni, Ofer (1998). Large deviations techniques and applications. Applications of Mathematics (New York) 38 (Second edition ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. xvi+396. ISBN 0-387-98406-2. MR1619036

- den Hollander, Frank (2000). Large deviations. Fields Institute Monographs 14. Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society. p. x+143. ISBN 0-8218-1989-5. MR1739680