Rasterisation

Rasterisation (or rasterization) is the task of taking an image described in a vector graphics format (shapes) and converting it into a raster image (pixels or dots) for output on a video display or printer, or for storage in a bitmap file format.

Contents |

Introduction

The term "rasterisation" can in general be applied to any process by which vector information can be converted into a raster format.

In normal usage, the term refers to the popular rendering algorithm for displaying three-dimensional shapes on a computer. Rasterization is currently the most popular technique for producing real-time 3D computer graphics. Real-time applications need to respond immediately to user input, and generally need to produce frame rates of at least 24 frames per second to achieve smooth animation.

Compared with other rendering techniques such as ray tracing, rasterization is extremely fast. However, rasterization is simply the process of computing the mapping from scene geometry to pixels and does not prescribe a particular way to compute the color of those pixels. Shading, including programmable shading, may be based on physical light transport, or artistic intent.

The process of rasterising 3D models onto a 2D plane for display on a computer screen is often carried out by fixed function hardware within the graphics pipeline. This is because there is no motivation for modifying the techniques for rasterisation used at render time and a special-purpose system allows for high efficiency.

Basic approach

The most basic rasterization algorithm takes a 3D scene, described as polygons, and renders it onto a 2D surface, usually a computer monitor. Polygons are themselves represented as collections of triangles. Triangles are represented by 3 vertices in 3D-space. At a very basic level, rasterizers simply take a stream of vertices, transform them into corresponding 2-dimensional points on the viewer’s monitor and fill in the transformed 2-dimensional triangles as appropriate.

Transformations

Transformations are usually performed by matrix multiplication. Quaternion math may also be used but that is outside the scope of this article. The main transformations are translation, scaling, rotation, and projection. A 3 dimensional vertex may be transformed by augmenting an extra variable (known as a "homogeneous variable") and left multiplying the resulting 4-component vertex by a 4 x 4 transformation matrix.

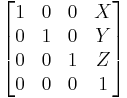

A translation is simply the movement of a point from its original location to another location in 3-space by a constant offset. Translations can be represented by the following matrix:

X, Y, and Z are the offsets in the 3 dimensions, respectively.

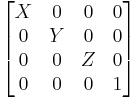

A scaling transformation is performed by multiplying the position of a vertex by a scalar value. This has the effect of scaling a vertex with respect to the origin. Scaling can be represented by the following matrix:

X, Y, and Z are the values by which each of the 3-dimensions are multiplied. Asymmetric scaling can be accomplished by varying the values of X, Y, and Z.

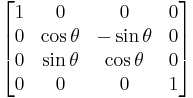

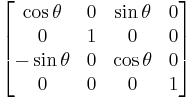

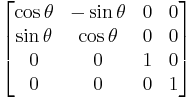

Rotation matrices depend on the axis around which a point is to be rotated.

Rotation about the X-axis:

Rotation about the Y-axis:

Rotation about the Z-axis:

θ in all each of these cases represent the angle of rotation.

A series of translation, scaling, and rotation matrices can logically describe most transformations. Rasterization systems generally use a transformation stack to move the stream of input vertices into place. The transformation stack is a standard stack which stores matrices. Incoming vertices are multiplied by the matrix stack.

As an illustrative example of how the transformation stack is used, imagine a simple scene with a single model of a person. The person is standing upright, facing an arbitrary direction while his head is turned in another direction. The person is also located at a certain offset from the origin. A stream of vertices, the model, would be loaded to represent the person. First, a translation matrix would be pushed onto the stack to move the model to the correct location. A scaling matrix would be pushed onto the stack to size the model correctly. A rotation about the y-axis would be pushed onto the stack to orient the model properly. Then, the stream of vertices representing the body would be sent through the rasterizer. Since the head is facing a different direction, the rotation matrix would be popped off the top of the stack and a different rotation matrix about the y-axis with a different angle would be pushed. Finally the stream of vertices representing the head would be sent to the rasterizer.

After all points have been transformed to their desired locations in 3-space with respect to the viewer, they must be transformed to the 2-D image plane. The simplest projection, the orthographic projection, simply involves removing the z component from transformed 3d vertices. Orthographic projections have the property that all parallel lines in 3-space will remain parallel in the 2-D representation. However, real world images are perspective images, with distant objects appearing smaller than objects close to the viewer. A perspective projection transformation needs to be applied to these points.

Conceptually, the idea is to transform the perspective viewing volume into the orthogonal viewing volume. The perspective viewing volume is a frustum, that is, a truncated pyramid. The orthographic viewing volume is a rectangular box, where both the near and far viewing planes are parallel to the image plane.

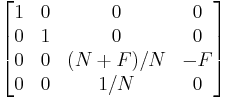

A perspective projection transformation can be represented by the following matrix:

F and N here are the distances of the far and near viewing planes, respectively. The resulting four vector will be a vector where the homogeneous variable is not 1. Homogenizing the vector, or multiplying it by the inverse of the homogeneous variable such that the homogeneous variable becomes unitary, gives us our resulting 2-D location in the x and y coordinates.

Clipping

Once triangle vertices are transformed to their proper 2d locations, some of these locations may be outside the viewing window, or the area on the screen to which pixels will actually be written. Clipping is the process of truncating triangles to fit them inside the viewing area.

The most common technique is the Sutherland-Hodgeman clipping algorithm. In this approach, each of the 4 edges of the image plane is tested at a time. For each edge, test all points to be rendered. If the point is outside the edge, the point is removed. For each triangle edge that is intersected by the image plane’s edge, that is, one vertex of the edge is inside the image and another is outside, a point is inserted at the intersection and the outside point is removed.

Scan conversion

The final step in the traditional rasterization process is to fill in the 2D triangles that are now in the image plane. This is also known as scan conversion.

The first problem to consider is whether or not to draw a pixel at all. For a pixel to be rendered, it must be within a triangle, and it must not be occluded, or blocked by another pixel. There are a number of algorithms to fill in pixels inside a triangle, the most popular of which is the scanline algorithm. Since it is difficult to know that the rasterization engine will draw all pixels from front to back, there must be some way of ensuring that pixels close to the viewer are not overwritten by pixels far away. A z buffer is the most common solution. The z buffer is a 2d array corresponding to the image plane which stores a depth value for each pixel. Whenever a pixel is drawn, it updates the z buffer with its depth value. Any new pixel must check its depth value against the z buffer value before it is drawn. Closer pixels are drawn and farther pixels are disregarded.

To find out a pixel's color, textures and shading calculations must be applied. A texture map is a bitmap that is applied to a triangle to define its look. Each triangle vertex is also associated with a texture and a texture coordinate (u,v) for normal 2-d textures in addition to its position coordinate. Every time a pixel on a triangle is rendered, the corresponding texel (or texture element) in the texture must be found. This is done by interpolating between the triangle’s vertices’ associated texture coordinates by the pixels on-screen distance from the vertices. In perspective projections, interpolation is performed on the texture coordinates divided by the depth of the vertex to avoid a problem known as perspective foreshortening (a process known as perspective texturing).

Before the final color of the pixel can be decided, a lighting calculation must be performed to shade the pixels based on any lights which may be present in the scene. There are generally three light types commonly used in scenes. Directional lights are lights which come from a single direction and have the same intensity throughout the entire scene. In real life, sunlight comes close to being a directional light, as the sun is so far away that rays from the sun appear parallel to Earth observers and the falloff is negligible. Point lights are lights with a definite position in space and radiate light evenly in all directions. Point lights are usually subject to some form of attenuation, or fall off in the intensity of light incident on objects farther away. Real life light sources experience quadratic falloff. Finally, spotlights are like real-life spotlights, with a definite point in space, a direction, and an angle defining the cone of the spotlight. There is also often an ambient light value that is added to all final lighting calculations to arbitrarily compensate for global illumination effects which rasterization can not calculate correctly.

There are a number of shading algorithms for rasterizers. All shading algorithms need to account for distance from light and the normal vector of the shaded object with respect to the incident direction of light. The fastest algorithms simply shade all pixels on any given triangle with a single lighting value, also known as flat shading. There is no way to create the illusion of smooth surfaces this way, except by subdividing into many small triangles. Algorithms can also separately shade vertices, and interpolate the lighting value of the vertices when drawing pixels. This is known as Gouraud shading. The slowest and most realistic approach is to calculate lighting separately for each pixel, also known as Phong shading. This performs bilinear interpolation of the normal vectors and uses the result to do local lighting calculation.

Acceleration techniques

To extract the maximum performance out of any rasterization engine, a minimum number of polygons should be sent to the renderer. A number of acceleration techniques have been developed over time to cull out objects which can not be seen.

Backface culling

The simplest way to cull polygons is to cull all polygons which face away from the viewer. This is known as backface culling. Since most 3d objects are fully enclosed, polygons facing away from a viewer are always blocked by polygons facing towards the viewer unless the viewer is inside the object. A polygon’s facing is defined by its winding, or the order in which its vertices are sent to the renderer. A renderer can define either clockwise or counterclockwise winding as front or back facing. Once a polygon has been transformed to screen space, its winding can be checked and if it is in the opposite direction, it is not drawn at all. Of course, backface culling can not be used with degenerate and unclosed volumes.

Spatial data structures

More advanced techniques use data structures to cull out objects which are either outside the viewing volume or are occluded by other objects. The most common data structures are binary space partitions, octrees, and cell and portal culling.

Further refinements

While the basic rasterization process has been known for decades, modern applications continue to make optimizations and additions to increase the range of possibilities for the rasterization rendering engine.

Texture filtering

Textures are created at specific resolutions, but since the surface they are applied to may be at any distance from the viewer, they can show up at arbitrary sizes on the final image. As a result, one pixel on screen usually does not correspond directly to one texel. Some form of filtering technique needs to be applied to create clean images at any distance. A variety of methods are available, with different tradeoffs between image quality and computational complexity.

Environment mapping

Environment mapping is a form of texture mapping in which the texture coordinates are view-dependent. One common application, for example, is to simulate reflection on a shiny object. One can environment map the interior of a room to a metal cup in a room. As the viewer moves about the cup, the texture coordinates of the cup’s vertices move accordingly, providing the illusion of reflective metal.

Bump mapping

Bump mapping is another form of texture mapping which does not provide pixels with color, but rather with depth. Especially with modern pixel shaders (see below), bump mapping creates the feel of view and lighting-dependent roughness on a surface to enhance realism greatly.

Level of detail

In many modern applications, the number of polygons in any scene can be phenomenal. However, a viewer in a scene will only be able to discern details of close-by objects. Level of detail algorithms vary the complexity of geometry as a function of distance to the viewer. Objects right in front of the viewer can be rendered at full complexity while objects further away can be simplified dynamically, or even replaced completely with sprites.

Shadows

Lighting calculations in the traditional rasterization process do not account for object occlusion. Shadow mapping and shadow volumes are two common modern techniques for creating shadows.

Hardware acceleration

Starting in the 1990s, hardware acceleration for normal consumer desktop computers has become the norm. Whereas graphics programmers had earlier relied on hand-coded assembly to make their programs run fast, most modern programs are written to interface with one of the existing graphics APIs, which drives a dedicated GPU.

The latest GPUs feature support for programmable pixel shaders which drastically improve the capabilities of programmers. The trend is towards full programmability of the graphics pipeline.

See also

- Hidden surface determination

- Bresenham's line algorithm for a typical method in rasterisation

- Scanline rendering for line-by-line rasterisation

- Rendering (computer graphics) for more general information

- Graphics pipeline for rasterisation in commodity graphics hardware

- Raster image processor for 2D rasterisation in printing systems

- Vector graphics for the source art

- Raster graphics for the result

- Raster to vector for conversion in the opposite direction

- Triangulated irregular network, a vector source for topography data, often rasterized as a (raster) digital elevation model.