r/K selection theory

In ecology, r/K selection theory relates to the selection of combinations of traits in an organism that trade off between quantity or quality of offspring. The focus upon either increased quantity of offspring at the expense of individual parental investment, or reduced quantity of offspring with a corresponding increased parental investment, is varied to promote success in particular environments. The theory was popular in the 1970s and 1980s when it was used as a heuristic device, but lost importance in the early 1990s as it was criticized by several empirical studies.[1][2] The r/K selection paradigm has been replaced by a "life-history" paradigm. However, this continues to incorporate many of the themes important to the r/K paradigm.[3]

The terminology of r/K-selection was coined by the ecologists Robert MacArthur and E. O. Wilson[4] based on their work on island biogeography.[5]

Contents |

Overview

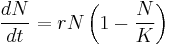

In r/K selection theory, selective pressures are hypothesised to drive evolution in one of two generalized directions: r- or K-selection.[4] These terms, r and K, are drawn from standard ecological algebra, as illustrated in the simplified Verhulst model of population dynamics:[6]

where r is the maximum growth rate of the population (N), and K is the carrying capacity of its local environmental setting. As the name implies, r-selected species are those that place an emphasis on a high growth rate, and typically exploit less-crowded ecological niches and produce many offspring, each of which has a relatively low probability of surviving to adulthood (i.e. high r, low K). By contrast, K-selected species display traits associated with living at densities close to carrying capacity, and typically are strong competitors in such crowded niches that invest more heavily in fewer offspring, each of which has a relatively high probability of surviving to adulthood (i.e. low r, high K). In the scientific literature, r-selected species are occasionally referred to as "opportunistic", while K-selected species are described as "equilibrium".[7]

r-selection (unstable environments)

In unstable or unpredictable environments, r-selection predominates as the ability to reproduce quickly is crucial. There is little advantage in adaptations that permit successful competition with other organisms, because the environment is likely to change again. Traits that are thought to be characteristic of r-selection include: high fecundity, small body size, early maturity onset, short generation time, and the ability to disperse offspring widely.

Organisms whose life history is subject to r-selection are often referred to as r-strategists or r-selected. Organisms who exhibit r-selected traits can range from bacteria and diatoms, to insects and weeds, to various semelparous cephalopods and mammals, particularly small rodents.

K-selection (stable environments)

In stable or predictable environments, K-selection predominates as the ability to compete successfully for limited resources is crucial and populations of K-selected organisms typically are very constant and close to the maximum that the environment can bear (unlike r-selected populations, where population sizes can change much more rapidly).

Traits that are thought to be characteristic of K-selection include: large body size, long life expectancy, and the production of fewer offspring, which require extensive parental care until they mature. Organisms whose life history is subject to K-selection are often referred to as K-strategists or K-selected. Organisms with K-selected traits include large organisms such as elephants, trees, humans and whales, but also smaller, long-lived organisms such as Arctic Terns.[8]

As a continuous spectrum

Although some organisms are identified as primarily r- or K-strategists, the majority of organisms do not follow this pattern. For instance, trees have traits such as longevity and strong competitiveness that characterise them as K-strategists. In reproduction, however, trees typically produce thousands of offspring and disperse them widely, traits characteristic of r-strategists. Similarly, reptiles such as sea turtles display both r- and K-traits: although sea turtles are large organisms with long lifespans (provided they reach adulthood), they produce large numbers of unnurtured offspring. Mammalian males tend to be r-type reproducers, whereas females tend to have K characteristics.[9]

In ecological succession

In areas of major ecological disruption or sterilisation (such as after a major volcanic eruption, as at Krakatoa or Mount Saint Helens), r- and K-strategists play distinct roles in the ecological succession that regenerates the ecosystem. Because of their higher reproductive rates and ecological opportunism, primary colonisers typically are r-strategists and they are followed by a succession of increasingly competitive flora and fauna. The ability of an environment to increase energetic content, through photosynthetic capture of solar energy, increases with the increase in complex biodiversity as r species proliferate to reach a peak possible with K strategies.[10]

Eventually a new equilibrium is approached (sometimes referred to as a climax community), with r-strategists gradually being replaced by K-strategists which are more competitive and better adapted to the emerging micro-environmental characteristics of the landscape. Traditionally, biodiversity was considered maximized at this stage, with introductions of new species resulting in the replacement and local extinction of endemic species.[11] However, the Intermediate Disturbance Hypothesis posits that intermediate levels of disturbance in a landscape create patches at different levels of succession, promoting coexistence of colonizers and competitors at the regional scale.

Status of the theory

In the 1970s and 1980s, several studies failed to produce experimental corroboration of the r/K theory, and, as a result, r/K selection theory was discarded by biologists studying life-history evolution by the early nineties.[12] Even though hundreds of papers used r/K selection theory to analyze life history data, and attempted to fit them into the r/K selection model, not a single study was able to demonstrate a correlation between fluctuation and adaptation or to show a tradeoff between r- and K-selected traits.[13]

Although r/K selection theory became widely used during the 1970s,[14][15][16][17] it also began to attract more critical attention.[18][19][20][21] In particular, an influential review by the ecologist Stephen C. Stearns drew attention to gaps in the theory, and to ambiguities in the interpretation of empirical data for testing it.[22] In 1981 a review of the r/K selection literature by Parry, demonstrated that there was no agreement among researchers using the theory about the definition of r and K selection, which led him to question whether the assumption of a relation between reproductive expenditure and packaging of offspring was justified.[23] A 1982 study by Templeton and Johnson, showed that in a population of Drosophila mercatorum under K selection the population actually produced a higher frequency of traits typically associated with r selection.[24] Several other studies contradicting the predictions of r/K selection theory were also published between 1977 and 1994.[25][26][27][28]

When Stearns reviewed the status of the theory in 1992[29] he noted that from 1977 to 1982 there was an average of 42 references to the theory per year in the BIOSIS literature search service, but from 1984 to 1989 the average dropped to 16 per year and continued to decline. He concluded that r/K theory was a once useful heuristic that no longer serves a purpose in life history theory.[30]

More recently the "Panarchy"[31] by theories of Adaptive Capacity and Resilience promoted by C. Holling and Lance Gunderson, have revived interest in the theory, as a way of integrating social systems, economics and ecology.

Reznick and colleagues (2002) reviewed the controversy regarding the r/K selection theory and wrote that "The distinguishing feature of the r- and K-selection paradigm was the focus on density-dependent selection as the important agent of selection on organisms’ life histories. This paradigm was challenged as it became clear that other factors, such as age-specific mortality, could provide a more mechanistic causative link between an environment and an optimal life history (Wilbur et al. 1974, Stearns 1976, 1977). The r- and K-selection paradigm was replaced by new paradigm that focused on age-specific mortality (Stearns 1976, Charlesworth 1980). This new life-history paradigm has matured into one that uses age-structured models as a framework to incorporate many of the themes important to the r–K paradigm."[3]

In humans

In his 1995 book Race, Evolution, and Behavior, the psychologist J. Philippe Rushton argues that different human races exhibit reproductive strategies characteristic of r/K selection theory. Rushton presents 60 different behavioral and anatomical variables, and asserts that East Asians, who have slightly longer lifespans, physically mature slower and are less sexually permissive relative to other races, are at the K end of the spectrum, while Africans, for whom the opposite is true, are more r-strategist.[32] Rushton's work has formed the theoretical basis for later studies from the hereditarian school of Race and Intelligence studies, for example in the work by Richard Lynn and Tatu Vanhanen. Among Rushton's many critics are evolutionary biologist Joseph L. Graves who has done extensive testing of the r/k selection theory with species of drosophila flies, argues that not only is r/K selection theory considered to be virtually useless when applied to human life history evolution, but Rushton himself does not apply the theory correctly, and displays a lack of understanding of evolutionary theory in general.[33] Graves also states that the sources for the biological data gathered in support of Rushton's hypothesis were misrepresented and that much of his social science data was collected by dubious means.[34] Other scholars have subsequently argued against Rushton's hypothesis on the basis that the concept of race is not supported by genetic evidence about the diversity of human populations.[35]

See also

- Adaptive capacity

- Evolutionary game theory

- Life history theory

- Ruderal species

- Trivers–Willard hypothesis

References

- ^ Roff, D. (1992). The Evolution of Life Histories: Theory and Analysis. London: Routledge, Chapman and Hall.. http://www.amazon.com/Evolution-Life-Histories-Theory-Analysis/dp/0412023911.

- ^ Stearns, S.C. (1992). The Evolution of Life Histories. Oxford: Oxford University Press.. http://www.amazon.com/Evolution-Life-Histories-Stephen-Stearns/dp/0198577419/ref=sr_1_2?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1302623680&sr=1-2.

- ^ a b Reznick, D.; Bryant, M. J.; Bashey, F. (2002). "R- ANDK-SELECTION REVISITED: THE ROLE OF POPULATION REGULATION IN LIFE-HISTORY EVOLUTION". Ecology 83 (6): 1509. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083[1509:RAKSRT]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0012-9658.

- ^ a b Pianka, E.R. (1970). "On r and K selection". American Naturalist 104 (940): 592–597. doi:10.1086/282697.

- ^ MacArthur, R. and Wilson, E.O. (1967). The Theory of Island Biogeography, Princeton University Press (2001 reprint), ISBN 0-691-08836-5M.

- ^ Verhulst, P.F. (1838). "Notice sur la loi que la population pursuit dans son accroissement". Corresp. Math. Phys. 10: 113–121.

- ^ For example: Weinbauer, M.G.; Höfle, M.G. (1 October 1998). "Distribution and Life Strategies of Two Bacterial Populations in a Eutrophic Lake". Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64 (10): 3776–3783. PMC 106546. PMID 9758799. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=106546.

- ^ "r and K selection". University of Miami Department of Biology. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- ^ Hrdy, Sarah Blaffer (2000), "Mother Nature: Maternal Instincts and How They Shape the Human Species" (Ballantine Books)

- ^ Gunderson, L. & Holling, C.S. (Eds) (2001), "Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems" (Island Press)

- ^ McNeely, J. A. (1994). "Lessons of the past: Forests and Biodiversity". Biodiversity and Conservation 3: 3–20. doi:10.1007/BF00115329. http://www.springerlink.com/content/t76125571tr97m64/.

- ^ Graves, Joseph L. "The Misuse of Life History Theory" in Fish, Jefferson (ed.) 2002. Race and Intelligence: Separating Science from Myth. Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates. p. 60

- ^ Graves, Joseph L. "The Misuse of Life History Theory" in Fish, Jefferson (ed.) 2002. Race and Intelligence: Separating Science from Myth. Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates. p. 65

- ^ Gadgil, M.; Solbrig, O.T. (1972). "Concept of r-selection and K-selection - evidence from wild flowers and some theoretical consideration". Am. Nat. 106: 14.

- ^ Long, T.; Long, G. (1974). "Effects of r-selection and K-selection on components of variance for 2 quantitative traits". Genetics 76 (3): 567–573. PMC 1213086. PMID 4208860. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1213086.

- ^ Grahame, J. (1977). "Reproductive effort and r-selection and K-selection in 2 species of Lacuna (Gastropoda-Prosobranchia)". Mar. Biol. 40 (3): 217–224. doi:10.1007/BF00390877.

- ^ Luckinbill, L.S. (1978). "r and K selection in experimental populations of Escherichia coli". Science 202 (4373): 1201–1203. doi:10.1126/science.202.4373.1201. PMID 17735406.

- ^ Wilbur, H.M.; Tinkle, D.W. and Collins, J.P. (1974). "Environmental certainty, trophic level, and resource availability in life history evolution". American Naturalist 108 (964): 805–816. doi:10.1086/282956.

- ^ Barbault, R. (1987). "Are still r-selection and K-selection operative concepts?". Acta Oecologica-Oecologia Generalis 8: 63–70.

- ^ Kuno, E. (1991). "Some strange properties of the logistic equation defined with r and K – inherent defects or artifacts". Researches on Population Ecology 33: 33–39. doi:10.1007/BF02514572.

- ^ Getz, W.M. (1993). "Metaphysiological and evolutionary dynamics of populations exploiting constant and interactive resources – r-K selection revisited". Evolutionary Ecology 7 (3): 287–305. doi:10.1007/BF01237746.

- ^ Stearns, S.C. (1977). "Evolution of life-history traits – critique of theory and a review of data" (PDF). Ann. Rev. of Ecology and Systematics 8: 145–171. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.08.110177.001045. http://faculty.washington.edu/kerrb/Stearns1977.pdf.

- ^ Parry, G.D. (1981) ‘The Meanings of r- and K-selection’, Oecologia 48: 260–81.

- ^ Templeton, A.R. and J.S. Johnson (1982) ‘Life History Evolution Under Pleiotropy and K-selection in a Natural Population of Drosophila mercatorum’, in J.S.F. Barker and W.T. Starmer (eds) Ecological Genetics and Evolution: The Cactus-Yeast-Drosophila System, pp. 225–39. Sydney: Academic Press.

- ^ Terry W. Snell and Charles E. King 1977. Lifespan and Fecundity Patterns in Rotifers: The Cost of Reproduction. Evolution. Vol. 31, No. 4 (Dec., 1977), pp. 882-890

- ^ r- and K-Selection in Drosophila pseudoobscura Charles E. Taylor and Cindra Condra. Evolution. Vol. 34, No. 6 (Nov., 1980), pp. 1183-1193

- ^ H. Hollocher and A. R. 1994. The Molecular Through Ecological Genetics of abnormal abdomen in Drosophila mercatorum. VI. The Non-Neutrality of the Y Chromosome rDNA PolymorphismTempleton Genetics, Vol 136, 1373-1384

- ^ Templeton, A.R., H. Hollocher and J.S. Johnson (1993) ‘The Molecular Through Ecological Genetics of Abnormal Abdomen in Drosophila mercatorum. V. Female Phenotypic Expression on Natural Genetic Backgrounds and in Natural Environments’, Genetics 134: 475–85.

- ^ Stearns, S.C. (1992). The Evolution of Life Histories. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-857741-6.

- ^ Graves, J. L. (2002). "What a tangled web he weaves Race, reproductive strategies and Rushton's life history theory". Anthropological Theory 2 (2): 2 131–154. doi:10.1177/1469962002002002627. http://ant.sagepub.com/content/2/2/131.short.

- ^ Gunderson, Lance H. and Holling C. S. (2001) "Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems" (Island Press)

- ^ Rushton, J. P. (1997). Race, Evolution, and Behavior: A Life History Perspective, Charles Darwin Research Institute, ISBN 0-9656836-2-1.

- ^ Graves, J. L. (2002). "What a tangled web he weaves Race, reproductive strategies and Rushton's life history theory". Anthropological Theory 2 (2): 2 131–154. doi:10.1177/1469962002002002627. http://ant.sagepub.com/content/2/2/131.short.

- ^ Graves, Joseph L. "The Misuse of Life History Theory: J. P. Rushton and the pseudoscience of racial hierarchy" in Fish, Jefferson. Ed. (2002) Race and Intelligence: Separating science from Myth. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. p 68

- ^ Long JC, Kittles RA (August 2003). "Human genetic diversity and the nonexistence of biological races". Human Biology 75 (4): 449–71. doi:10.1353/hub.2003.0058. PMID 14655871.