Quadrature amplitude modulation

| Passband modulation |

|---|

| Analog modulation |

| AM · SSB · QAM · FM · PM · SM |

| Digital modulation |

| FSK · MFSK · ASK · OOK · PSK · QAM MSK · CPM · PPM · TCM · SC-FDE |

| Spread spectrum |

| CSS · DSSS · FHSS · THSS |

| See also: Demodulation, modem, line coding, PAM, PWM, PCM |

Quadrature amplitude modulation (QAM) ( /ˈkwɑːm/ or /ˈkæm/ or simply "Q-A-M") is both an analog and a digital modulation scheme. It conveys two analog message signals, or two digital bit streams, by changing (modulating) the amplitudes of two carrier waves, using the amplitude-shift keying (ASK) digital modulation scheme or amplitude modulation (AM) analog modulation scheme. The two carrier waves, usually sinusoids, are out of phase with each other by 90° and are thus called quadrature carriers or quadrature components — hence the name of the scheme. The modulated waves are summed, and the resulting waveform is a combination of both phase-shift keying (PSK) and amplitude-shift keying (ASK), or (in the analog case) of phase modulation (PM) and amplitude modulation. In the digital QAM case, a finite number of at least two phases and at least two amplitudes are used. PSK modulators are often designed using the QAM principle, but are not considered as QAM since the amplitude of the modulated carrier signal is constant. QAM is used extensively as a modulation scheme for digital telecommunication systems. Spectral efficiencies of 6 bits/s/Hz can be achieved with QAM.[1]

QAM modulation is being used in optical fiber systems as bit rates increase – QAM16 and QAM64 can be optically emulated with a 3-path interferometer.[2]

Contents |

Digital QAM

Like all modulation schemes, QAM conveys data by changing some aspect of a carrier signal, or the carrier wave, (usually a sinusoid) in response to a data signal. In the case of QAM, the amplitude of two waves, 90 degrees out-of-phase with each other (in quadrature) are changed (modulated or keyed) to represent the data signal. Amplitude modulating two carriers in quadrature can be equivalently viewed as both amplitude modulating and phase modulating a single carrier.

Phase modulation (analog PM) and phase-shift keying (digital PSK) can be regarded as a special case of QAM, where the magnitude of the modulating signal is a constant, with only the phase varying. This can also be extended to frequency modulation (FM) and frequency-shift keying (FSK), for these can be regarded as a special case of phase modulation.

Analog QAM

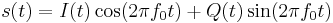

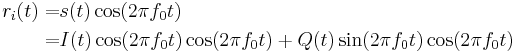

When transmitting two signals by modulating them with QAM, the transmitted signal will be of the form:

,

,

where  and

and  are the modulating signals and

are the modulating signals and  is the carrier frequency.

is the carrier frequency.

At the receiver, these two modulating signals can be demodulated using a coherent demodulator. Such a receiver multiplies the received signal separately with both a cosine and sine signal to produce the received estimates of  and

and  respectively. Because of the orthogonality property of the carrier signals, it is possible to detect the modulating signals independently.

respectively. Because of the orthogonality property of the carrier signals, it is possible to detect the modulating signals independently.

In the ideal case  is demodulated by multiplying the transmitted signal with a cosine signal:

is demodulated by multiplying the transmitted signal with a cosine signal:

Using standard trigonometric identities, we can write it as:

Low-pass filtering  removes the high frequency terms (containing

removes the high frequency terms (containing  ), leaving only the

), leaving only the  term. This filtered signal is unaffected by

term. This filtered signal is unaffected by  , showing that the in-phase component can be received independently of the quadrature component. Similarly, we may multiply

, showing that the in-phase component can be received independently of the quadrature component. Similarly, we may multiply  by a sine wave and then low-pass filter to extract

by a sine wave and then low-pass filter to extract  .

.

The phase of the received signal is assumed to be known accurately at the receiver. If the demodulating phase is even a little off, it results in crosstalk between the modulated signals. This issue of carrier synchronization at the receiver must be handled somehow in QAM systems. The coherent demodulator needs to be exactly in phase with the received signal, or otherwise the modulated signals cannot be independently received. For example analog television systems transmit a burst of the transmitting colour subcarrier after each horizontal synchronization pulse for reference.

Analog QAM is used in NTSC and PAL television systems, where the I- and Q-signals carry the components of chroma (colour) information. "Compatible QAM" or C-QUAM is used in AM stereo radio to carry the stereo difference information.

Fourier analysis of QAM

In the frequency domain, QAM has a similar spectral pattern to DSB-SC modulation. Using the properties of the Fourier transform, we find that:

where S(f), MI(f) and MQ(f) are the Fourier transforms (frequency-domain representations) of s(t), I(t) and Q(t), respectively.

Quantized QAM

Like many digital modulation schemes, the constellation diagram is a useful representation. In QAM, the constellation points are usually arranged in a square grid with equal vertical and horizontal spacing, although other configurations are possible (e.g. Cross-QAM). Since in digital telecommunications the data are usually binary, the number of points in the grid is usually a power of 2 (2, 4, 8 ...). Since QAM is usually square, some of these are rare—the most common forms are 16-QAM, 64-QAM and 256-QAM. By moving to a higher-order constellation, it is possible to transmit more bits per symbol. However, if the mean energy of the constellation is to remain the same (by way of making a fair comparison), the points must be closer together and are thus more susceptible to noise and other corruption; this results in a higher bit error rate and so higher-order QAM can deliver more data less reliably than lower-order QAM, for constant mean constellation energy.

If data-rates beyond those offered by 8-PSK are required, it is more usual to move to QAM since it achieves a greater distance between adjacent points in the I-Q plane by distributing the points more evenly. The complicating factor is that the points are no longer all the same amplitude and so the demodulator must now correctly detect both phase and amplitude, rather than just phase.

64-QAM and 256-QAM are often used in digital cable television and cable modem applications. In the United States, 64-QAM and 256-QAM are the mandated modulation schemes for digital cable (see QAM tuner) as standardised by the SCTE in the standard ANSI/SCTE 07 2000. Note that many marketing people will refer to these as QAM-64 and QAM-256. In the UK, 16-QAM and 64-QAM are currently used for digital terrestrial television (Freeview and Top Up TV) and 256-QAM is planned for Freeview-HD.

Communication systems designed to achieve very high levels of spectral efficiency usually employ very dense QAM constellations. One example is the ITU-T G.hn standard for networking over existing home wiring (coaxial cable, phone lines and power lines), which employs constellations up to 4096-QAM (12 bits/symbol). Another example is VDSL2 technology for copper twisted pairs, whose constellation size goes up to 32768 points.

Ideal structure

Transmitter

The following picture shows the ideal structure of a QAM transmitter, with a carrier frequency  and the frequency response of the transmitter's filter

and the frequency response of the transmitter's filter  :

:

First the flow of bits to be transmitted is split into two equal parts: this process generates two independent signals to be transmitted. They are encoded separately just like they were in an amplitude-shift keying (ASK) modulator. Then one channel (the one "in phase") is multiplied by a cosine, while the other channel (in "quadrature") is multiplied by a sine. This way there is a phase of 90° between them. They are simply added one to the other and sent through the real channel.

The sent signal can be expressed in the form:

where ![v_c[n]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/34aff838d5ca0efba06aae1af87eb4de.png) and

and ![v_s[n]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/5b17ff918789aa638204f3108a07c77c.png) are the voltages applied in response to the

are the voltages applied in response to the  th symbol to the cosine and sine waves respectively.

th symbol to the cosine and sine waves respectively.

Receiver

The receiver simply performs the inverse process of the transmitter. Its ideal structure is shown in the picture below with  the receive filter's frequency response :

the receive filter's frequency response :

Multiplying by a cosine (or a sine) and by a low-pass filter it is possible to extract the component in phase (or in quadrature). Then there is only an ASK demodulator and the two flows of data are merged back.

In practice, there is an unknown phase delay between the transmitter and receiver that must be compensated by synchronization of the receivers local oscillator, i.e. the sine and cosine functions in the above figure. In mobile applications, there will often be an offset in the relative frequency as well, due to the possible presence of a Doppler shift proportional to the relative velocity of the transmitter and receiver. Both the phase and frequency variations introduced by the channel must be compensated by properly tuning the sine and cosine components, which requires a phase reference, and is typically accomplished using a Phase-Locked Loop (PLL).

In any application, the low-pass filter will be within hr (t): here it was shown just to be clearer.

Quantized QAM performance

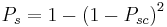

The following definitions are needed in determining error rates:

= Number of symbols in modulation constellation

= Number of symbols in modulation constellation = Energy-per-bit

= Energy-per-bit = Energy-per-symbol =

= Energy-per-symbol =  with k bits per symbol

with k bits per symbol = Noise power spectral density (W/Hz)

= Noise power spectral density (W/Hz) = Probability of bit-error

= Probability of bit-error = Probability of bit-error per carrier

= Probability of bit-error per carrier = Probability of symbol-error

= Probability of symbol-error = Probability of symbol-error per carrier

= Probability of symbol-error per carrier .

.

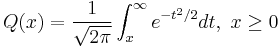

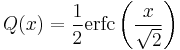

is related to the complementary Gaussian error function by:

is related to the complementary Gaussian error function by:  , which is the probability that x will be under the tail of the Gaussian PDF towards positive infinity.

, which is the probability that x will be under the tail of the Gaussian PDF towards positive infinity.

The error rates quoted here are those in additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN).

Where coordinates for constellation points are given in this article, note that they represent a non-normalised constellation. That is, if a particular mean average energy were required (e.g. unit average energy), the constellation would need to be linearly scaled.

Rectangular QAM

Rectangular QAM constellations are, in general, sub-optimal in the sense that they do not maximally space the constellation points for a given energy. However, they have the considerable advantage that they may be easily transmitted as two pulse amplitude modulation (PAM) signals on quadrature carriers, and can be easily demodulated. The non-square constellations, dealt with below, achieve marginally better bit-error rate (BER) but are harder to modulate and demodulate.

The first rectangular QAM constellation usually encountered is 16-QAM, the constellation diagram for which is shown here. A Gray coded bit-assignment is also given. The reason that 16-QAM is usually the first is that a brief consideration reveals that 2-QAM and 4-QAM are in fact binary phase-shift keying (BPSK) and quadrature phase-shift keying (QPSK), respectively. Also, the error-rate performance of 8-QAM is close to that of 16-QAM (only about 0.5 dB better), but its data rate is only three-quarters that of 16-QAM.

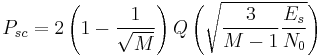

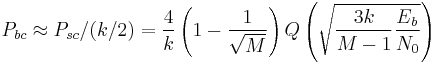

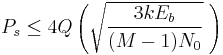

Expressions for the symbol-error rate of rectangular QAM are not hard to derive but yield rather unpleasant expressions. For an even number of bits per symbol,  , exact expressions are available. They are most easily expressed in a per carrier sense:

, exact expressions are available. They are most easily expressed in a per carrier sense:

,

,

so

.

.

The bit-error rate depends on the bit to symbol mapping, but for  and a Gray-coded assignment—so that we can assume each symbol error causes only one bit error—the bit-error rate is approximately

and a Gray-coded assignment—so that we can assume each symbol error causes only one bit error—the bit-error rate is approximately

.

.

Since the carriers are independent, the overall bit error rate is the same as the per-carrier error rate, just like BPSK and QPSK.

.

.

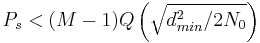

Odd-k QAM

For odd  , such as 8-QAM (

, such as 8-QAM ( ) it is harder to obtain symbol-error rates, but a tight upper bound is:

) it is harder to obtain symbol-error rates, but a tight upper bound is:

.

.

Two rectangular 8-QAM constellations are shown below without bit assignments. These both have the same minimum distance between symbol points, and thus the same symbol-error rate (to a first approximation).

The exact bit-error rate,  will depend on the bit-assignment.

will depend on the bit-assignment.

Note that both of these constellations are seldom used in practice, as the non-rectangular version of 8-QAM is optimal. Example of second constellation's usage: LDPC and 8-QAM.

Non-rectangular QAM

It is the nature of QAM that most orders of constellations can be constructed in many different ways and it is neither possible nor instructive to cover them all here. This article instead presents two, lower-order constellations.

Two diagrams of circular QAM constellation are shown, for 8-QAM and 16-QAM. The circular 8-QAM constellation is known to be the optimal 8-QAM constellation in the sense of requiring the least mean power for a given minimum Euclidean distance. The 16-QAM constellation is suboptimal although the optimal one may be constructed along the same lines as the 8-QAM constellation. The circular constellation highlights the relationship between QAM and PSK. Other orders of constellation may be constructed along similar (or very different) lines. It is consequently hard to establish expressions for the error rates of non-rectangular QAM since it necessarily depends on the constellation. Nevertheless, an obvious upper bound to the rate is related to the minimum Euclidean distance of the constellation (the shortest straight-line distance between two points):

.

.

Again, the bit-error rate will depend on the assignment of bits to symbols.

Although, in general, there is a non-rectangular constellation that is optimal for a particular  , they are not often used since the rectangular QAMs are much easier to modulate and demodulate.

, they are not often used since the rectangular QAMs are much easier to modulate and demodulate.

Interference and noise

In moving to a higher order QAM constellation (higher data rate and mode) in hostile RF/microwave QAM application environments, such as in broadcasting or telecommunications, multipath interference typically increases. There is a spreading of the spots in the constellation, decreasing the separation between adjacent states, making it difficult for the receiver to decode the signal appropriately. In other words, there is reduced noise immunity . There are several test parameter measurements which help determine an optimal QAM mode for a specific operating environment. The following three are most significant:[3]

- Carrier/interference ratio

- Carrier-to-noise ratio

- Threshold-to-noise ratio

See also

- Modulation for other examples of modulation techniques

- Phase-shift keying

- Amplitude and phase-shift keying or Asymmetric phase-shift keying (APSK)

- Carrierless Amplitude Phase Modulation (CAP)

- Random modulation

- QAM tuner for HDTV

References

- ^ UAS UAV communications links

- ^ Kylia products, dwdm mux demux, 90 degree optical hybrid, d(q) psk demodulatorssingle polarization

- ^ Howard Friedenberg and Sunil Naik. "Hitless Space Diversity STL Enables IP+Audio in Narrow STL Bands". 2005 National Association of Broadcasters Annual Convention. http://www.moseleysb.com/mb/whitepapers/friedenberg.pdf. Retrieved April 17, 2005.

The notation used here has mainly (but not exclusively) been taken from

- John G. Proakis, "Digital Communications, 3rd Edition",

External links

- How imperfections affect QAM constellation

- Microwave Phase Shifters Overview by Herley General Microwave

- QAM Baseband Modem - EPN-online.co.uk

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![\begin{align}

r_i(t) = & \frac{1}{2} I(t) \left[1 %2B \cos (4 \pi f_0 t)\right] %2B \frac{1}{2} Q(t) \sin (4 \pi f_0 t) \\

= & \frac{1}{2} I(t) %2B \frac{1}{2} [I(t) \cos (4 \pi f_0 t) %2B \frac{1}{2} Q(t) \sin (4 \pi f_0 t)]

\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/31a44ad5bf5c506bb97b343709195779.png)

![S(f) = \frac{1}{2}\left[ M_I(f - f_0) %2B M_I(f %2B f_0) \right] %2B \frac{1}{2j}\left[ M_Q(f - f_0) - M_Q(f %2B f_0) \right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/acc017193e5ceeb20435e24066a2f4d1.png)

![s(t) = \sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty} \left[ v_c [n] \cdot h_t (t - n T_s) \cos (2 \pi f_0 t) -

v_s[n] \cdot h_t (t - n T_s) \sin (2 \pi f_0 t) \right],](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/b07991c6a71fdf2c272266303e71e2b1.png)