Proton-transfer-reaction mass spectrometry

Proton-transfer-reaction mass spectrometry (PTR-MS) is a very sensitive technique for online monitoring of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in ambient air developed by scientists at the Institut für Ionenphysik at the Leopold-Franzens University in Innsbruck, Austria[1]. A PTR-MS instrument consists of an ion source that is directly connected to a drift tube (in contrast to SIFT-MS no mass filter is interconnected) and an analyzing system (quadrupole mass analyzer or time-of-flight mass spectrometer). Commercially available PTR-MS instruments have a response time of about 100 ms and reach a detection limit in the single digit pptv region. Established fields of application are environmental research, food and flavour science, biological research, medicine, etc.[2][3]

Contents |

Theory

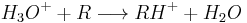

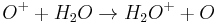

With H3O+ as the primary ion the proton transfer process is (with  being the trace component)

being the trace component)

(1).

(1).

Reaction (1) is only possible if energetically allowed, i.e. if the proton affinity of  is higher than the proton affinity of H2O (691 kJ/mol [4]). As most components of ambient air possess a lower proton affinity than H2O (e.g. N2, O2, Ar, CO2, etc.) the H3O+ ions only reacts with VOC trace components and the air itself acts as a buffer gas. Moreover due to the low number of trace components one can assume that the total number of H3O+ ions remains nearly unchanged, which leads to the equation[5]

is higher than the proton affinity of H2O (691 kJ/mol [4]). As most components of ambient air possess a lower proton affinity than H2O (e.g. N2, O2, Ar, CO2, etc.) the H3O+ ions only reacts with VOC trace components and the air itself acts as a buffer gas. Moreover due to the low number of trace components one can assume that the total number of H3O+ ions remains nearly unchanged, which leads to the equation[5]

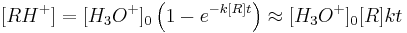

(2).

(2).

In equation (2)  is the density of product ions,

is the density of product ions,  is the density of primary ions in absence of reactant molecules in the buffer gas,

is the density of primary ions in absence of reactant molecules in the buffer gas,  is the reaction rate constant and

is the reaction rate constant and  is the average time the ions need to pass the reaction region. With a PTR-MS instrument the number of product and of primary ions can be measured, the reaction rate constant can be found in literature for most substances[6] and the reaction time can be derived from the set instrument parameters. Therefore the absolute concentration of trace constituents

is the average time the ions need to pass the reaction region. With a PTR-MS instrument the number of product and of primary ions can be measured, the reaction rate constant can be found in literature for most substances[6] and the reaction time can be derived from the set instrument parameters. Therefore the absolute concentration of trace constituents  can be easily calculated without the need of calibration or gas standards. Furthermore it gets obvious that the overall sensitivity of a PTR-MS instrument is mainly dependent on the primary / reagent ion yield. Fig. 1 gives an overview of several published (in peer-reviewed journals) reagent ion yields during the last decades and the corresponding sensitivities.

can be easily calculated without the need of calibration or gas standards. Furthermore it gets obvious that the overall sensitivity of a PTR-MS instrument is mainly dependent on the primary / reagent ion yield. Fig. 1 gives an overview of several published (in peer-reviewed journals) reagent ion yields during the last decades and the corresponding sensitivities.

Technology

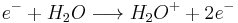

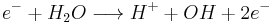

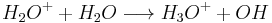

In commercial PTR-MS instruments water vapour is ionized in a hollow cathode discharge:

.

.

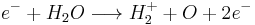

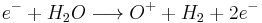

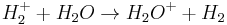

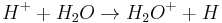

After the discharge a short drift tube is used to form very pure (>99.5%[5]) H3O+ via ion-molecule reactions:

.

.

Due to the high purity of the primary ions a mass filter between the ion source and the reaction drift tube is not necessary and the H3O+ ions can be injected directly. The absence of this mass filter in turn greatly reduces losses of primary ions and leads eventually to an outstandingly low detection limit of the whole instrument. In the reaction drift tube a vacuum pump is continuously drawing through air containing the VOCs one wants to analyze. At the end of the drift tube the protonated molecules are mass analyzed (Quadrupole mass analyzer or Time-of-flight mass spectrometer) and detected.

Advantages of PTR-MS

- Low fragmentation: Only a small amount of energy is transferred during the ionization process (compared to e.g. electron impact ionization), therefore fragmentation is suppressed and the obtained mass spectra are easily interpretable.

- No sample preparation is necessary: VOC containing air and fluids headspaces can be analyzed directly.

- Real-time measurements: With a typical response time of 100 ms VOCs can be monitored on-line.

- Real-time quantification: Absolute concentrations are obtained directly without previous calibration measurements.

- Compact and robust setup: Due to the simple design and the low number of parts needed for a PTR-MS instrument, it can be built in into space saving and even mobile housings.

- Easy to operate: For the operation of a PTR-MS only electric power and a small amount of distilled water are needed. Unlike other techniques no gas cylinders are needed for buffer gas or calibration standards.

Disadvantages of PTR-MS

- Not all molecules detectable: Because only molecules with a proton affinity higher than water can be detected by PTR-MS, the technology is not suitable for all fields of application.

- Maximum measurable concentration limited: Equation (2) is based on the assumption that the decrease of primary ions is neglectable, therefore the total concentration of VOCs in air must not exceed about 10 ppmv. Otherwise the instrument's response will not be linear anymore and the concentration calculation will be incorrect.

Applications

The most common applications for the PTR-MS technique are (including some relevant publications):[2][3]

- Environmental research[7][8]

- Waste incineration

- Food and flavour science[9]

- Biological research[10]

- Process monitoring

- Indoor air quality[11][12][13]

- Medicine and biotechnology[14][15]

- Homeland Security[16][17]

Extensive reviews about PTR-MS and some of its applications were published in Mass Spectrometry Reviews by Joost de Gouw et al. (2007)[18] and in Chemical Reviews by R.S. Blake et al. (2009)[19]. A special issue of the Journal of Breath Research dedicated to PTR-MS applications in medical research was published in 2009[20].

Examples

Food Science

Fig. 2 shows a typical PTR-MS measurement performed in food and flavor research. The test person swallows a sip of a vanillin flavored drink and breathes via his nose into a heated inlet device coupled to a PTR-MS instrument. Due to the high time resolution and sensitivity of the instrument used here, the development of vanillin in the person's breath can be monitored in real-time (please note that isoprene is shown in this figure because it is a product of human metabolism and therefore acts as an indicator for the breath cycles). The data can be used for food design, i.e. for adjusting the intensity and duration of vanillin flavor tasted by the consumer.

Another example for the application of PTR-MS in food science was published in 2008 by C. Lindinger et al.[24] in Analytical Chemistry. This publication found great response even in non-scientific media[25][26]. Lindinger et al. developed a method to convert "dry" data from a PTR-MS instrument that measured headspace air from different coffee samples into expressions of flavour (e.g. "woody", "winey", "flowery", etc.) and showed that the obtained flavor profiles matched nicely to the ones created by a panel of European coffee tasting experts.

Air quality analysis

In Fig. 3 a mass spectrum of air inside a laboratory (obtained with a time-of-flight (TOF) based PTR-MS instrument), is shown. The peaks on masses 19, 37 and 55 m/z (and their isotopes) represent the reagent ions (H3O+) and their clusters. On 30 and 32 m/z NO+ and O2+, which are both impurities originating from the ion source, appear. All other peaks correspond to compounds present in typical laboratory air (e.g. high intensity of protonated acetone on 59 m/z). If one takes into account that virtually all peaks visible in Fig. 3 are in fact double, triple or multiple peaks (isobaric compounds) it becomes obivious that for PTR-MS instruments selectivity is at least as important as sensitivity, especially when complex samples / compositions are analyzed. Methods to handle this issue have been suggestested in literature as:

- High mass resolution: When the PTR source is coupled to a high resolution mass spectrometer isobaric compounds can be distinguished and substances can be identified via their exact mass[27].

- Switchable reagent ions: Some PTR-MS instruments are despite of the lack of a mass filter between the ion source and the drift tube capable of switching the reagent ions (e.g. to NO+ or O2+; Charge-exchange ionization). With the additional information obtained by using different reagent ions a much higher level of selectivity can be reached, e.g. some isomeric molecules can be distinguished[28].

References

- ^ A. Hansel, A. Jordan, R. Holzinger, P. Prazeller W. Vogel, W. Lindinger, Proton transfer reaction mass spectrometry: on-line trace gas analysis at ppb level, Int. J. of Mass Spectrom. and Ion Proc., 149/150, 609-619 (1995).

- ^ a b http://www.ionicon.com/documentation/publications.html

- ^ a b http://www.uibk.ac.at/ionen-angewandte-physik/umwelt/publications/index.html.en

- ^ R.S. Blake, P.S. Monks, A.M. Ellis, Proton-Transfer Reaction Mass Spectrometry, Chem. Rev., 109, 861-896 (2009)

- ^ a b W. Lindinger, A. Hansel and A. Jordan, On-line monitoring of volatile organic compounds at pptv levels by means of Proton-Transfer-Reaction Mass-Spectrometry (PTR-MS): Medical applications, food control and environmental research, Review paper, Int. J. Mass Spectrom. Ion Proc., 173, 191-241 (1998).

- ^ Y. Ikezoe, S. Matsuoka and A. Viggiano, Gas Phase Ion-Molecule Reaction Rate Constants through 1986, Maruzen Company Ltd., Tokyo, (1987).

- ^ M. Müller, M. Graus, T. M. Ruuskanen, R. Schnitzhofer, I. Bamberger, L. Kaser, T. Titzmann, L. Hörtnagl, G. Wohlfahrt, T. Karl, A. Hansel: First eddy covariance flux measurements by PTR-TOF, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 3, 387–395, (2010).

- ^ R. Beale, P. S. Liss, J. L. Dixon, P. D. Nightingale: Quantification of oxygenated volatile organic compounds in seawater by membrane inlet-proton transfer reaction/mass spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta (2011).

- ^ F. Biasioli, C. Yeretzian, F. Gasperi, T. D. Märk: PTR-MS monitoring of VOCs and BVOCs in food science and technology, Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 30/7, (2011).

- ^ M. Simpraga, H. Verbeeck, M. Demarcke, É. Joó, O. Pokorska, C. Amelynck, N. Schoon, J. Dewulf, H. Van Langenhove, B. Heinesch, M. Aubinet, Q. Laffineur, J.-F. Müller, K. Steppe: Clear link between drought stress, photosynthesis and biogenic volatile organic compounds in Fagus sylvatica L., Atmospheric Environment, 45, 5254-5259, (2011).

- ^ A. Wisthaler, P. Strom-Tejsen, L. Fang, T. J. Arnaud, A. Hansel, T. D. Märk, D. P. Wyon, PTR-MS Assessment of Photocatalytic and Sorption-Based Purification of Recirculated Cabin Air during Simulated 7-h Flights with High Passenger Density. Environ. Sci. Technol., 1/41, 229-234, (2007).

- ^ B. Kolarik, P. Wargocki, A. Skorek-Osikowska, A. Wisthaler: The effect of a photocatalytic air purifier on indoor air quality quantified using different measuring methods, Building and Environment, 45, 1434–1440, (2010).

- ^ K.H. Han, J.S. Zhang, H.N. Knudsen, P. Wargocki, H. Chen, P.K. Varshney, B. Guo: Development of a novel methodology for indoor emission source identification, Atmospheric Environment, 45, 3034-3045, (2011).

- ^ J. Herbig, M. Müller, S. Schallhart, T. Titzmann, M. Graus, A. Hansel, On-line breath analysis with PTR-TOF, J. Breath Res., 3, 027004, (2009).

- ^ C. Brunner, W. Szymczak, V. Höllriegl, S. Mörtl, H. Oelmez, A. Bergner, R. M. Huber, C. Hoeschen, U. Oeh, Discrimination of cancerous and non-cancerous cell lines by headspace-analysis with PTR-MS, Anal. Bioanal. Chem., 397, 2315-2324, (2010).

- ^ S. Jürschik, P. Sulzer, F. Petersson, C. A. Mayhew, A. Jordan, B. Agarwal, S. Haidacher, H. Seehauser, K. Becker, T. D. Märk: Proton transfer reaction mass spectrometry for the sensitive and rapid real-time detection of solid high explosives in air and water, Anal Bioanal Chem 398, 2813–2820, (2010).

- ^ F. Petersson, P. Sulzer, C.A. Mayhew, P. Watts, A. Jordan, L. Märk, T.D. Märk: Real-time trace detection and identification of chemical warfare agent simulants using recent advances in proton transfer reaction time-of-flight mass spectrometry, Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom., 23, 3875–3880, (2009).

- ^ J. de Gouw, C. Warneke, T. Karl, G. Eerdekens, C. van der Veen, R. Fall: Measurement of Volatile Organic Compounds in the Earth's Atmosphere using Proton-Transfer-Reaction Mass Spectrometry, Mass Spectrometry Reviews, 26, 223-257, (2007).

- ^ R. S. Blake, P. S. Monks, A. M. Ellis: Proton-Transfer Reaction Mass Spectrometry. Chem. Rev., 109/3, 861-896, (2009).

- ^ Jens Herbig and Anton Amann (editors), Journal of Breath Research, Proton Transfer Reaction-Mass Spectrometry Applications in Medical Research; Volume 3, Number 2, June 2009.

- ^ http://www.ionicon.com/products/accessories/nase.html

- ^ http://www.ionicon.com/products/ptr-ms/ptrqms/hs-ptr-qms_500.html

- ^ http://www.ionicon.com/products/ptr-ms/ptrtofms/ptrtof8000.html

- ^ C. Lindinger, D. Labbe, P. Pollien, A. Rytz, M. A. Juillerat, C. Yeretzian, I. Blank, When Machine Tastes Coffee: Instrumental Approach To Predict the Sensory Profile of Espresso Coffee, Anal. Chem., 80/5, 1574-1581, (2008).

- ^ http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/23359908/

- ^ http://www.nytimes.com/2008/02/19/science/19objava.html?ex=1361077200&en=393e1220ba7a4cf1&ei=5124&partner=permalink&exprod=permalink

- ^ A. Jordan, S. Haidacher, G. Hanel, E. Hartungen, L. Märk, H. Seehauser, R. Schottkowsky, P. Sulzer, T.D. Märk: A high resolution and high sensitivity time-of-flight proton-transfer-reaction mass spectrometer (PTR-TOF-MS), International Journal of Mass Spectrometry, 286, 122–128, (2009).

- ^ A. Jordan, S. Haidacher, G. Hanel, E. Hartungen, J. Herbig, L. Märk, R. Schottkowsky, H. Seehauser, P. Sulzer, T.D. Märk: An online ultra-high sensitivity proton-transfer-reaction mass-spectrometer combined with switchable reagent ion capability (PTR+SRI-MS), International Journal of Mass Spectrometry, 286, 32-38, (2009).