Proto-Indo-European nouns

The nouns of the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE), their morphology and semantics, have been reconstructed by modern linguists based on similarities found across all Indo-European languages.

Contents |

Morphology

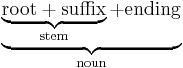

The nouns are, just like PIE verbs, inflected by adding an ending (E) to a stem. The stem is the carrier of the basic meaning, and is composed of a root (R) and a suffix (S). The ending carries information about the case and number. Thus, the general morphological form of a noun is R+S+E.

Each PIE root has an inherent meaning, usually that of a verb. Suffixation yields different derived nouns with different meaning (e. g. *déh₃-tor-s "giver" and *déh₃-o-s "gift", both with the verbal root *deh₃- "give").

Summing up, the suffix has the role of a derivational morpheme, and the ending that of an inflectional morpheme.

Athematic and thematic nouns

A fundamental distinction is made between thematic and athematic nouns. Thematic nouns have a stem ending in a thematic vowel, *-o- in almost all cases, sometimes ablauting to *-e-. The accent is fixed on the same syllable throughout the inflection. The stem of athematic nouns ends in a consonant. They have a complex system of accent and ablaut alterations between the root, the stem and the ending (see below). This type is generally held as more archaic.

In the 19th century, stems used to be classified by their last sound into vowel (i-, u-, a-, ya-, o-, yo-stems) and consonantic stems (the rest). However, since *i and *u have been explained as vocalic allophones of underlying consonants (the glides *y and *w, respectively),[1] and what used to be reconstructed as *ā and *a has been reduced to *eh₂ and *h₂e in the modern laryngeal theory, the only real vowel stems left are the o-stems, corresponding to what is now usually called the thematic stems. However, since syllabic allophones of the glides were phonemicized as real vowels in all daughter languages, and all the daughters except for the Anatolian branch have completely lost the laryngeals, terms like i-stems, a-stems etc. still continue to be widely used to subclassify athematic nouns.

Root nouns

PIE also had a class of monosyllabic athematic or so-called root nouns which lack the derivational suffix, the ending being directly added to the root (as in *dóm-s, derived from *dem- "build"[2]). These nouns can also be interpreted as having a zero suffix or one without a phonetic body (*dóm-Ø-s).

Verbal stems have corresponding morphological features, the root present and the root aorist.

Primary and secondary derivation

The first suffix added to a root is considered a primary derivation (as in *déh₃-tor-s), and if additional suffixes are added, or if a suffix is added to a root noun, this makes a secondary derivation.

Prefixes and reduplication

Some nouns were formed with prefixes. An example is *ni-sd-os "nest", derived from the verb *sed- "sit" by adding a local prefix and thus meaning "where [the bird] sits" or the like.

A special kind of prefixation, called reduplication, uses the first part of the root plus a vowel as a prefix. For example, *kʷel(h₁)- "turn" gives *kʷe-kʷl(h₁)-os "wheel". This type of derivation is also found in verbs, mainly to form the perfect.

Grammatical categories

PIE nouns, as well as adjectives and pronouns, are subject to the system of PIE nominal inflection, inflecting for eight or nine cases: nominative, accusative, vocative, genitive, dative, instrumental, ablative, locative, and possibly a directive or allative.[3] Three numbers were distinguished: singular, dual and plural, with a distinction between a plural of collective and one of countable nouns.

The so-called strong cases are the nominative and the vocative for all numbers, and the accusative case for singular and dual (and possibly plural as well), and the rest are the weak cases. This classification is relevant for inflecting the athematic nouns of different accent classes (see below).

Late PIE had three genders: masculine, feminine and neuter. Originally, there probably were only an animate (masculine/feminine) and an inanimate (neuter) gender.[4] This view is supported by the existence of certain classes of Latin and Ancient Greek adjectives which inflect only for two sets of endings, one for masculine and feminine, the other for neuter. Further evidence comes from the Anatolian languages which exhibit only the animate and the inanimate gender.[5] However, this could also mean that Proto-Anatolian inherited a three-gender PIE system, and subsequently Hittite and other Old Anatolian languages eliminated the feminine by merging it with the masculine.[6] The typically feminine ā-stems are considered to originate from the same form as the neuter plural, originally an abstract/collective derivational suffix *-h₂.[7]

Case endings

Here are two typical reconstructions of the case endings. Beekes[8] does not give separate tables for the thematic and athematic endings:

| Singular | Dual | Plural | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animate | Neuter | Animate | Neuter | Animate | Neuter | |

| Nominative | *-s, *-Ø | *-m, *-Ø | *-h₁(e) | *-ih₁ | *-es | *-h₂, *-Ø |

| Accusative | *-m | *-m, *-Ø | *-ih₁ | *-ih₁ | *-ns | *-h₂, *-Ø |

| Vocative | *-Ø | *-m, *-Ø | *-h₁(e) | *-ih₁ | *-es | *-h₂, *-Ø |

| Genitive | *-(o)s | *-h₁e | *-om | |||

| Dative | *-(e)i | *-me | *-mus | |||

| Instrumental | *-(e)h₁ | *-bʰih₁ | *-bʰi | |||

| Ablative | *-(o)s | *-ios | *-ios | |||

| Locative | *-i, *-Ø | *-h₁ou | *-su | |||

Fortson[9] reconstructs the athematic and the thematic endings, but lacks the dual for the weak cases. The thematic forms in the following table include the thematic vowel, which is really part of the suffix, not the ending.

The thematic vowel *-o- ablauts to *-e- only in word-final position in the vocative singular, and before *h₂ in the neuter nominative and accusative plural. The vocative singular is also the only case for which the thematic nouns show accent retraction, a leftward shift of the accent, denoted by *-ĕ.

| Singular | Dual | Plural | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Athematic | Thematic | Athematic | Thematic | Athematic | Thematic | |||||||

| Animate | Neuter | Animate | Neuter | Animate | Neuter | Animate | Neuter | Animate | Neuter | Animate | Neuter | |

| Nominative | *-s | *-Ø | *-os | *-om | *-h₁ | *-ih₁ | *-oh₁ > *-ō | *-oih₁ | *-es | *-h₂ | *-oes > *-ōs | *-eh₂ > *-ā |

| Accusative | *-m | *-Ø | *-om | *-om | *-h₁ | *-ih₁ | *-oh₁ > *-ō | *-oih₁ | *-ns | *-h₂ | *-ons | *-eh₂ > *-ā |

| Vocative | *-Ø | *-ĕ | *-h₁ | *-oh₁ > *-ō | *-es | *-oes > *-ōs | ||||||

| Genitive | *-s | *-os? | *-ōm | *-ōm | ||||||||

| Dative | *-ei | *-oei > *-ōi | *-bʰ-† | *-o(i)bʰ-† | ||||||||

| Instrumental | *-h₁ | *-oh₁ > *-ō | *-bʰ-† | *-o(i)bʰ-† | ||||||||

| Ablative | *-s | *-o(h₂)at > *-ōt | *-bʰ-† | *-o(i)bʰ-† | ||||||||

| Locative | *-i, *-ا | *-oi | *-su | *-oisu | ||||||||

†The dative, instrumental and ablative plural endings probably contained a *bʰ but are of uncertain structure otherwise. They might also have been of post-PIE date.

§For athematic nouns, an endingless locative is reconstructed in addition to the ordinary locative singular in *-i. In contrast to the other weak cases, it typically has full or lengthened grade of the stem.

Athematic accent/ablaut classes

Polysyllabic athematic nouns (type R+S+E) exhibit four characteristic patterns that include accent and ablaut alternations throughout the paradigm between the root, the stem and the ending. Root nouns (type R+E) show similar behaviour, but with only two patterns.[10] A distinction can be made between "kinetic" types (Ancient Greek kinetikos = moving) and "static" types (Ancient Greek statikos = holding still).

| Type | Case | R | S | E | Example | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polysyllabic nouns | ||||||

| acrostatic (or acrodynamic) (akros = beginning) |

strong | ó/ḗ | Ø | Ø | nom. sg. *nókʷ-t-s | "night" |

| weak | é | Ø | Ø | gen. sg. *nékʷ-t-s | ||

| proterokinetic (or proterodynamic) (proteros = before) |

strong | é | Ø | Ø | nom. sg. *mén-ti-s | "thought" |

| weak | Ø | é | Ø | gen. sg. *mn̥-téy-s | ||

| hysterokinetic (or hysterodynamic) (hystera = womb, presumably "inside" here) |

strong | Ø | é | Ø | nom. sg. *ph₂-tér-s[11] | "father" |

| weak | Ø | Ø | é | gen. sg. *ph₂-tr-és | ||

| amphikinetic (or amphidynamic) (amphis = on both sides) |

strong | é | o | Ø | nom. sg. *pént-oh₂-s | "path" |

| weak | Ø | Ø | é | gen. sg. *pn̥t-h₂-és | ||

| Root nouns | ||||||

| acrostatic | strong | ó/ḗ | Ø | nom. sg. *dóm-s[11] | "house" | |

| weak | é | Ø | gen. sg. *dém-s | |||

| amphikinetic (?) | strong | é/ḗ | Ø | nom. sg. *dyḗw-s | "heaven, god of heaven or day" | |

| weak | Ø | é | gen. sg. *diw-és | |||

There is an unexpected o-grade of the suffix in the strong cases of polysyllabic amphikinetic nouns. Another unusual property of this class is the locative singular having a stressed e-grade suffix.

The classification of the amphikinetic root nouns is disputed.[12] Since these words have no suffix, they differ from the amphikinetic polysyllables in the strong cases (no o-grade) and in the locative singular (no e-grade suffix). Some scholars prefer to call these nouns amphikinetic and the corresponding polysyllables holokinetic (or holodynamic, from holos = whole).[13]

Some[14] also list mesostatic (meso = middle) and teleutostatic types, with the accent fixed on the suffix and the ending, respectively, but their existence in PIE is disputed.[15] The classes can then be grouped into three static (acrostatic, mesostatic, teleutostatic) and three or four mobile (proterokinetic, hysterokinetic, amphikinetic, holokinetic) paradigms.

Heteroclitic stems

Some athematic noun stems have different final consonants in different cases; these are termed heteroclitic stems. Most of these stems end in *-r- in the nominative and accusative singular, and in *-n- in the other cases. Examples of such r/n-stems include the acrostatic neuter *wód-r̥ "water", genitive *wéd-n-s; and *peh₂-wr̥ "fire", genitive *ph₂-wen-s or similar.

A possible l/n-stem is *seh₂-wōl "sun", genitive *sh₂-wén-s or the like.[16]

Examples

The following are example declensions of a number of different types of nouns, based on the reconstruction of Ringe (2006).[17]

| acrostatic root noun | acrostatic lengthened root noun | amphikinetic (?) root noun | hysterokinetic r-stem | amphikinetic n-stem | hysterokinetic n-stem | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gloss | night (f.) | moon (m.) | foot (m.) | father (m.) | lake (m.) | bull (m.) | |

| sing. | nom. | *nókʷts | *mḗh₁n̥s | *pṓds | *ph₂tḗr | *léymō | *uksḗn |

| voc. | *nókʷt | *mḗh₁n̥s | *pód | *ph₂tér | *léymon | *úksen | |

| acc. | *nókʷtm̥ | *mḗh₁n̥sm̥ | *pódm̥ | *ph₂térm̥ | *léymonm̥ | *uksénm̥ | |

| inst. | *nékʷt(e)h₁ | *méh₁n̥s(e)h₁ | *pedéh₁ | *ph₂tr̥éh₁ | *limnéh₁ | *uksn̥éh₁ | |

| dat. | *nékʷtey | *méh₁n̥sey | *pedéy | *ph₂tr̥éy | *limnéy | *uksn̥éy | |

| abl. | *nékʷts | *méh₁n̥sos | *pedés | *ph₂tr̥és | *limnés | *uksn̥és | |

| gen. | *nékʷts | *méh₁n̥sos | *pedés | *ph₂tr̥és | *limnés | *uksn̥és | |

| loc. | *nékʷt(i) | *méh₁n̥s(i) | *péd(i) | *ph₂tér(i) | *limén(i) | *uksén(i) | |

| dual | nom.-voc.-acc. | *nókʷth₁e | *mḗh₁n̥sh₁e | *pódh₁e | *ph₂térh₁e | *léymonh₁e | *uksénh₁e |

| plur. | n.-v. | *nókʷtes | *mḗh₁n̥ses | *pódes | *ph₂téres | *léymones | *uksénes |

| acc. | *nókʷtn̥s | *mḗh₁n̥sn̥s | *pódn̥s | *ph₂térn̥s | *léymonn̥s | *uksénn̥s | |

| inst. | *nékʷtbʰi | *méh₁n̥sbʰi | *pedbʰí | *ph₂tr̥bʰí | *limn̥bʰí | *uksn̥bʰí | |

| dat.-abl. | *nékʷtm̥os | *méh₁n̥smos | *pedmós | *ph₂tr̥mós | *limn̥mós | *uksn̥mós | |

| gen. | *nékʷtoHom | *méh₁n̥soHom | *pedóHom | *ph₂tr̥óHom | *limn̥óHom | *uksn̥óHom | |

| loc. | *nékʷtsu | *méh₁n̥su | *pedsú | *ph₂tr̥sú | *limn̥sú | *uksn̥sú | |

| proterokinetic neuter r/n-stem | amphikinetic collective neuter r/n-stem | amphikinetic m-stem | proterokinetic ti-stem | proterokinetic tu-stem | proterokinetic neuter u-stem | ||

| gloss | water (n.) | water(s) (n.) | earth (f.) | thought (f.) | taste (m.) | tree (n.) | |

| sing. | nom. | *wódr̥ | *wédōr | *dʰéǵʰōm | *méntis | *ǵéwstus | *dóru |

| voc. | *wódr̥ | *wédōr | *dʰéǵʰom | *ménti | *ǵéwstu | *dóru | |

| acc. | *wódr̥ | *wédōr | *dʰéǵʰōm | *méntim | *ǵéwstum | *dóru | |

| inst. | *udénh₁ | *udnéh₁ | *ǵʰméh₁ | *mn̥tíh₁ | *ǵustúh₁ | *drúh₁ | |

| dat. | *udéney | *udnéy | *ǵʰméy | *mn̥téyey | *ǵustéwey | *dréwey | |

| abl. | *udéns | *udnés | *ǵʰmés | *mn̥téys | *ǵustéws | *dréws | |

| gen. | *udéns | *udnés | *ǵʰmés | *mn̥téys | *ǵustéws | *dréws | |

| loc. | *udén(i) | *udén(i) | *ǵʰdʰsém(i) | *mn̥téy (-ēy) | *ǵustéw(i) | *dréw(i) | |

| dual | nom.-voc.-acc. | *méntih₁ | *ǵéwstuh₁ | *dórwih₁ | |||

| plur. | n.-v. | *ménteyes | *ǵéwstewes | *dóruh₂ | |||

| acc. | *méntins | *ǵéwstuns | *dóruh₂ | ||||

| inst. | *mn̥tíbʰi | *ǵustúbʰi | *drúbʰi | ||||

| dat.-abl. | *mn̥tímos | *ǵustúmos | *drúmos | ||||

| gen. | *mn̥téyoHom | *ǵustéwoHom | *dréwoHom | ||||

| loc. | *mn̥tísu | *ǵustúsu | *drúsu | ||||

| neuter s-stem | proterokinetic h₂-stem | hysterokinetic h₂-stem | eh₂-stem (ā-stem) | o-stem | neuter o-stem | ||

| gloss | cloud (n.) | woman (f.) | tongue (f.) | grain (f.) | nest (m.) | work (n.) | |

| sing. | nom. | *nébʰos | *gʷḗn | *dn̥ǵʰwéh₂s | *dʰoHnéh₂ | *nisdós | *wérǵom |

| voc. | *nébʰos | *gʷḗn | *dń̥ǵʰweh₂ | *dʰoHn[á] | *nisdé | *wérǵom | |

| acc. | *nébʰos | *gʷénh₂m̥ | *dn̥ǵʰwéh₂m (-ām) | *dʰoHnéh₂m (-ā́m) | *nisdóm | *wérǵom | |

| inst. | *nébʰes(e)h₁ | *gʷnéh₂(e)h₁ | *dn̥ǵʰuh₂éh₁ | *dʰoHnéh₂(e)h₁ | *nisdóh₁ | *wérǵoh₁ | |

| dat. | *nébʰesey | *gʷnéh₂ey | *dn̥ǵʰuh₂éy | *dʰoHnéh₂ey | *nisdóey | *wérǵoey | |

| abl. | *nébʰesos | *gʷnéh₂s | *dn̥ǵʰuh₂és | *dʰoHnéh₂s | *nisdéad | *wérǵead | |

| gen. | *nébʰesos | *gʷnéh₂s | *dn̥ǵʰuh₂és | *dʰoHnéh₂s | *nisdósyo | *wérǵosyo | |

| loc. | *nébʰes(i) | *gʷnéh₂(i) | *dn̥ǵʰwéh₂(i) | *dʰoHnéh₂(i) | *nisdéy | *wérǵey | |

| dual | nom.-voc.-acc. | *nébʰesih₁ | *gʷénh₂h₁e | *dn̥ǵʰwéh₂h₁e | ? | *nisdóh₁ | *wérǵoy(h₁) |

| plur. | n.-v. | *nébʰōs | *gʷénh₂es | *dn̥ǵʰwéh₂es | *dʰoHnéh₂es | *nisdóes | *wérǵeh₂ |

| acc. | *nébʰōs | *gʷénh₂n̥s | *dn̥ǵʰwéh₂ns (-ās) | *dʰoHnéh₂ns (-ās) | *nisdóns | *wérǵeh₂ | |

| inst. | *nébʰesbʰi | *gʷnéh₂bʰi | *dn̥ǵʰuh₂bʰí | *dʰoHnéh₂bʰi | *nisdṓys | *wérǵōys | |

| dat.-abl. | *nébʰesmos | *gʷnéh₂mos | *dn̥ǵʰuh₂mós | *dʰoHnéh₂mos | *nisdó(y)mos | *wérǵo(y)mos | |

| gen. | *nébʰesoHom | *gʷnéh₂oHom | *dn̥ǵʰuh₂óHom | *dʰoHnéh₂oHom | *nisdóoHom | *wérǵooHom | |

| loc. | *nébʰesu | *gʷnéh₂su | *dn̥ǵʰuh₂sú | *dʰoHnéh₂su | *nisdóysu | *wérǵoysu | |

Derivation

New words are formed in several ways, namely:

- by ablaut alternations (the root consonantism is intact, but vocalization changes), e.g. *ḱernes "horned" from *ḱernos "horn, roe". Many PIE adjectives formed this way were subsequently nominalized in daughter languages.

- by alternating accent (i.e. switching to another accent/ablaut class), e.g. *bʰóros "burden", but *bʰorós "carrier"

- by derivational suffixes (possibly coupled with changes 1 and 2)

- by reduplication

- by combining lexical morphemes themselves (compounding); e.g. PIE *drḱ-h₂ḱru "tear", literally "eye-bitter"

Notes

- ^ Words like *mén-ti-s are athematic because the *i is just the vocalic form of the glide *y, the full grade of the suffix being *-tey-. See Proto-Indo-European phonology: Vowels for further information on the syllabification rules for PIE sonorants.

- ^ *dem- "build" is also reconstructed as *demh₂- which could mean that "house" is actually *dómh₂-s.

- ^ Fortson (2004:102)

- ^ Fortson (2004:103)

- ^ Mallory, J. P. and D. Q. Adams. 2006. The Oxford introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European world. P.59

- ^ Google Books: The Ancient Languages of Asia Minor

- ^ Luraghi, Silvia. 2009. The origin of the feminine gender in PIE. An old problem in a new perspective. In Bubenik, V., J. Hewson and S. Rose (ed.)Grammatical change in Indo-European languages.

- ^ Beekes (1995)

- ^ Fortson (2004:113)

- ^ Fortson (2004:108–109)

- ^ a b Actually, only *ph₂tḗr and *dṓm can be reconstructed, but these forms could have developed from the regular ones (*ph₂térs and *dóms, respectively) via Szemerényi's law.

- ^ Fortson (2004:109ff)

- ^ Meier-Brügger, Fritz & Mayrhofer (2003:216)

- ^ Meier-Brügger, Fritz & Mayrhofer (2003, F 315)

- ^ Fortson (2004:107)

- ^ Fortson (2004:110–111)

- ^ Ringe (2006:47–50)

References

- Fortson, Benjamin W., IV (2004), Indo-European Language and Culture, Blackwell Publishing, ISBN 1-4051-0316-7

- Beekes, Robert S. P. (1995), Comparative Indo-European Linguistics: An Introduction, Amsterdam: John Benjamins, ISBN 90-272-2150-2 (Europe), ISBN 1-55619-504-4 (U.S.)

- Meier-Brügger, Michael; Fritz, Matthias; Mayrhofer, Manfred (2003), Indo-European Linguistics, Berlin; New York: Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 3110174332

- Ringe, Don (2006), From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-955229-0

|

||||||||||||||