Prior probability

In Bayesian statistical inference, a prior probability distribution, often called simply the prior, of an uncertain quantity p (for example, suppose p is the proportion of voters who will vote for the politician named Smith in a future election) is the probability distribution that would express one's uncertainty about p before the "data" (for example, an opinion poll) is taken into account. It is meant to attribute uncertainty rather than randomness to the uncertain quantity. The unknown quantity may be a parameter or latent variable.

One applies Bayes' theorem, multiplying the prior by the likelihood function and then normalizing, to get the posterior probability distribution, which is the conditional distribution of the uncertain quantity given the data.

A prior is often the purely subjective assessment of an experienced expert. Some will choose a conjugate prior when they can, to make calculation of the posterior distribution easier.

Parameters of prior distributions are called hyperparameters, to distinguish them from parameters of the model of the underlying data. For instance, if one is using a beta distribution to model the distribution of the parameter p of a Bernoulli distribution, then:

- p is a parameter of the underlying system (Bernoulli distribution), and

- α and β are parameters of the prior distribution (beta distribution), hence hyperparameters.

Contents |

Informative priors

An informative prior expresses specific, definite information about a variable. An example is a prior distribution for the temperature at noon tomorrow. A reasonable approach is to make the prior a normal distribution with expected value equal to today's noontime temperature, with variance equal to the day-to-day variance of atmospheric temperature, or a distribution of the temperature for that day of the year.

This example has a property in common with many priors, namely, that the posterior from one problem (today's temperature) becomes the prior for another problem (tomorrow's temperature); pre-existing evidence which has already been taken into account is part of the prior and as more evidence accumulates the prior is determined largely by the evidence rather than any original assumption, provided that the original assumption admitted the possibility of what the evidence is suggesting. The terms "prior" and "posterior" are generally relative to a specific datum or observation.

Uninformative priors

An uninformative prior expresses vague or general information about a variable. The term "uninformative prior" may be somewhat of a misnomer; often, such a prior might be called a not very informative prior, or an objective prior, i.e. one that's not subjectively elicited. Uninformative priors can express "objective" information such as "the variable is positive" or "the variable is less than some limit".

The simplest and oldest rule for determining a non-informative prior is the principle of indifference, which assigns equal probabilities to all possibilities.

In parameter estimation problems, the use of an uninformative prior typically yields results which are not too different from conventional statistical analysis, as the likelihood function often yields more information than the uninformative prior.

Some attempts have been made at finding a priori probabilities, i.e. probability distributions in some sense logically required by the nature of one's state of uncertainty; these are a subject of philosophical controversy, with Bayesians being roughly divided into two schools: "objective Bayesians", who believe such priors exist in many useful situations, and "subjective Bayesians" who believe that in practice priors usually represent subjective judgements of opinion that cannot be rigorously justified (Williamson 2010). Perhaps the strongest arguments for objective Bayesianism were given by Edwin T. Jaynes.

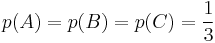

As an example of an a priori prior, due to Jaynes (2003), consider a situation in which one knows a ball has been hidden under one of three cups, A, B or C, but no other information is available about its location. In this case a uniform prior of  seems intuitively like the only reasonable choice. More formally, we can see that the problem remains the same if we swap around the labels ("A", "B" and "C") of the cups. It would therefore be odd to choose a prior for which a permutation of the labels would cause a change in our predictions about which cup the ball will be found under; the uniform prior is the only one which preserves this invariance. If one accepts this invariance principle then one can see that the uniform prior is the logically correct prior to represent this state of knowledge. It should be noted that this prior is "objective" in the sense of being the correct choice to represent a particular state of knowledge, but it is not objective in the sense of being an observer-independent feature of the world: in reality the ball exists under a particular cup, and it only makes sense to speak of probabilities in this situation if there is an observer with limited knowledge about the system.

seems intuitively like the only reasonable choice. More formally, we can see that the problem remains the same if we swap around the labels ("A", "B" and "C") of the cups. It would therefore be odd to choose a prior for which a permutation of the labels would cause a change in our predictions about which cup the ball will be found under; the uniform prior is the only one which preserves this invariance. If one accepts this invariance principle then one can see that the uniform prior is the logically correct prior to represent this state of knowledge. It should be noted that this prior is "objective" in the sense of being the correct choice to represent a particular state of knowledge, but it is not objective in the sense of being an observer-independent feature of the world: in reality the ball exists under a particular cup, and it only makes sense to speak of probabilities in this situation if there is an observer with limited knowledge about the system.

As a more contentious example, Jaynes published an argument (Jaynes 1968) based on Lie groups that suggests that the prior representing complete uncertainty about a probability should be the Haldane prior p−1(1 − p)−1. The example Jaynes gives is of finding a chemical in a lab and asking whether it will dissolve in water in repeated experiments. The Haldane prior[1] gives by far the most weight to  and

and  , indicating that the sample will either dissolve every time or never dissolve, with equal probability. However, if one has observed samples of the chemical to dissolve in one experiment and not to dissolve in another experiment then this prior is updated to the uniform distribution on the interval [0, 1]. This is obtained by applying Bayes' theorem to the data set consisting of one observation of dissolving and one of not dissolving, using the above prior. The Haldane prior has been criticized on the grounds that it yields an improper posterior distribution that puts 100% of the probability content at either p = 0 or at p = 1 if a finite number of observations have given the same result. The Jeffreys prior p−1/2(1 − p)−1/2 is therefore preferred (see below).

, indicating that the sample will either dissolve every time or never dissolve, with equal probability. However, if one has observed samples of the chemical to dissolve in one experiment and not to dissolve in another experiment then this prior is updated to the uniform distribution on the interval [0, 1]. This is obtained by applying Bayes' theorem to the data set consisting of one observation of dissolving and one of not dissolving, using the above prior. The Haldane prior has been criticized on the grounds that it yields an improper posterior distribution that puts 100% of the probability content at either p = 0 or at p = 1 if a finite number of observations have given the same result. The Jeffreys prior p−1/2(1 − p)−1/2 is therefore preferred (see below).

Priors can be constructed which are proportional to the Haar measure if the parameter space X carries a natural group structure which leaves invariant our Bayesian state of knowledge (Jaynes, 1968). This can be seen as a generalisation of the invariance principle used to justify the uniform prior over the three cups in the example above. For example, in physics we might expect that an experiment will give the same results regardless of our choice of the origin of a coordinate system. This induces the group structure of the translation group on X, which determines the prior probability as a constant improper prior. Similarly, some measurements are naturally invariant to the choice of an arbitrary scale (i.e., it doesn't matter if we use centimeters or inches, we should get results that are physically the same). In such a case, the scale group is the natural group structure, and the corresponding prior on X is proportional to 1/x. It sometimes matters whether we use the left-invariant or right-invariant Haar measure. For example, the left and right invariant Haar measures on the affine group are not equal. Berger (1985, p. 413) argues that the right-invariant Haar measure is the correct choice.

Another idea, championed by Edwin T. Jaynes, is to use the principle of maximum entropy (MAXENT). The motivation is that the Shannon entropy of a probability distribution measures the amount of information contained in the distribution. The larger the entropy, the less information is provided by the distribution. Thus, by maximizing the entropy over a suitable set of probability distributions on X, one finds the distribution that is least informative in the sense that it contains the least amount of information consistent with the constraints that define the set. For example, the maximum entropy prior on a discrete space, given only that the probability is normalized to 1, is the prior that assigns equal probability to each state. And in the continuous case, the maximum entropy prior given that the density is normalized with mean zero and variance unity is the standard normal distribution. The principle of minimum cross-entropy generalizes MAXENT to the case of "updating" an arbitrary prior distribution with suitability constraints in the maximum-entropy sense.

A related idea, reference priors, was introduced by José-Miguel Bernardo. Here, the idea is to maximize the expected Kullback–Leibler divergence of the posterior distribution relative to the prior. This maximizes the expected posterior information about X when the prior density is p(x); thus, in some sense, p(x) is the "least informative" prior about X. The reference prior is defined in the asymptotic limit, i.e., one considers the limit of the priors so obtained as the number of data points goes to infinity. Reference priors are often the objective prior of choice in multivariate problems, since other rules (e.g., Jeffreys' rule) may result in priors with problematic behavior.

Objective prior distributions may also be derived from other principles, such as information or coding theory (see e.g. minimum description length) or frequentist statistics (see frequentist matching).

Philosophical problems associated with uninformative priors are associated with the choice of an appropriate metric, or measurement scale. Suppose we want a prior for the running speed of a runner who is unknown to us. We could specify, say, a normal distribution as the prior for his speed, but alternatively we could specify a normal prior for the time he takes to complete 100 metres, which is proportional to the reciprocal of the first prior. These are very different priors, but it is not clear which is to be preferred. Jaynes' often-overlooked method of transformation groups can answer this question in some situations.[2]

Similarly, if asked to estimate an unknown proportion between 0 and 1, we might say that all proportions are equally likely and use a uniform prior. Alternatively, we might say that all orders of magnitude for the proportion are equally likely, the logarithmic prior, which is the uniform prior on the logarithm of proportion. The Jeffreys prior attempts to solve this problem by computing a prior which expresses the same belief no matter which metric is used. The Jeffreys prior for an unknown proportion p is p−1/2(1 − p)−1/2, which differs from Jaynes' recommendation.

Priors based on notions of algorithmic probability are used in inductive inference as a basis for induction in very general settings.

Practical problems associated with uninformative priors include the requirement that the posterior distribution be proper. The usual uninformative priors on continuous, unbounded variables are improper. This need not be a problem if the posterior distribution is proper. Another issue of importance is that if an uninformative prior is to be used routinely, i.e., with many different data sets, it should have good frequentist properties. Normally a Bayesian would not be concerned with such issues, but it can be important in this situation. For example, one would want any decision rule based on the posterior distribution to be admissible under the adopted loss function. Unfortunately, admissibility is often difficult to check, although some results are known (e.g., Berger and Strawderman 1996). The issue is particularly acute with hierarchical Bayes models; the usual priors (e.g., Jeffreys' prior) may give badly inadmissible decision rules if employed at the higher levels of the hierarchy.

Improper priors

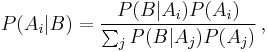

If Bayes' theorem is written as

then it is clear that it would remain true if all the prior probabilities P(Ai) and P(Aj) were multiplied by a given constant; the same would be true for a continuous random variable. The posterior probabilities will still sum (or integrate) to 1 even if the prior values do not, and so the priors only need to be specified in the correct proportion.

Taking this idea further, in many cases the sum or integral of the prior values may not even need to be finite to get sensible answers for the posterior probabilities. When this is the case, the prior is called an improper prior.

Some statisticians use improper priors as uninformative priors. For example, if they need a prior distribution for the mean and variance of a random variable, they may assume p(m, v) ~ 1/v (for v > 0) which would suggest that any value for the mean is "equally likely" and that a value for the positive variance becomes "less likely" in inverse proportion to its value. Many authors (Lindley, 1973; De Groot, 1937; Kass and Wasserman, 1996) warn against the danger of over-interpreting those priors since they are not probability densities. The only relevance they have is found in the corresponding posterior, as long as it is well-defined for all observations. (The Haldane prior is a typical counterexample.)

Examples

Examples of improper priors include:

- Beta(0,0), the beta distribution for α=0, β=0.

- The uniform distribution on an infinite interval (i.e., a half-line or the entire real line).

- The logarithmic prior on the positive reals.

Other priors

The concept of algorithmic probability provides a route to specifying prior probabilities based on the relative complexity of the alternative models being considered.

See also

Notes

- ^ This prior was proposed by J.B.S. Haldane in "A note on inverse probability", Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 28, 55–61, 1932, available online at http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract?aid=1733860. See also J. Haldane, "The precision of observed values of small frequencies", Biometrika, 35:297–300, 1948, available online at http://www.jstor.org/pss/2332350.

- ^ Jaynes (1968), pp. 17, see also Jaynes (2003), chapter 12. Note that chapter 12 is not available in the online preprint but can be previewed via Google Books.

References

- Rubin, Donald B.; Gelman, Andrew; John B. Carlin; Stern, Hal (2003). Bayesian Data Analysis (2nd ed.). Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC. ISBN 1-58488-388-X. MR2027492.

- Berger, James O. (1985). Statistical decision theory and Bayesian analysis. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-96098-8. MR0804611.

- Berger, James O.; Strawderman, William E. (1996). "Choice of hierarchical priors: admissibility in estimation of normal means". Annals of Statistics 24 (3): 931–951. doi:10.1214/aos/1032526950. MR1401831. Zbl 0865.62004.

- Bernardo, Jose M. (1979). "Reference Posterior Distributions for Bayesian Inference". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B 41 (2): 113–147. JSTOR 2985028. MR0547240.

- James O. Berger; José M. Bernardo; Dongchu Sun (2009). "The formal definition of reference priors". Annals of Statistics 37 (2): 905–938. arXiv:0904.0156.

- Jaynes, Edwin T. (Sept 1968). "Prior Probabilities". IEEE Transactions on Systems Science and Cybernetics 4 (3): 227–241. doi:10.1109/TSSC.1968.300117. http://bayes.wustl.edu/etj/articles/prior.pdf. Retrieved 2009-03-27.

- Reprinted in Rosenkrantz, Roger D. (1989). E. T. Jaynes: papers on probability, statistics, and statistical physics. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 116–130. ISBN 90-277-1448-7.

- Jaynes, Edwin T. (2003). Probability Theory: The Logic of Science. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521592712. http://www-biba.inrialpes.fr/Jaynes/prob.html.

- Williamson, Jon (2010). "review of Bruno di Finetti. Philosophical Lectures on Probability". Philosophia Mathematica 18 (1): 130–135. doi:10.1093/philmat/nkp019. http://www.kent.ac.uk/secl/philosophy/jw/2009/deFinetti.pdf. Retrieved 2010-07-02.