Pressure coefficient

The pressure coefficient is a dimensionless number which describes the relative pressures throughout a flow field in fluid dynamics. The pressure coefficient is used in aerodynamics and hydrodynamics. Every point in a fluid flow field has its own unique pressure coefficient,  .

.

In many situations in aerodynamics and hydrodynamics, the pressure coefficient at a point near a body is independent of body size. Consequently an engineering model can be tested in a wind tunnel or water tunnel, pressure coefficients can be determined at critical locations around the model, and these pressure coefficients can be used with confidence to predict the fluid pressure at those critical locations around a full-size aircraft or boat.

Contents |

Incompressible flow

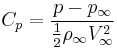

The pressure coefficient is a very useful parameter for studying the flow of incompressible fluids such as water, and also the low-speed flow of compressible fluids such as air. The relationship between the dimensionless coefficient and the dimensional numbers is [1] [2]:

where:

is the pressure at the point at which pressure coefficient is being evaluated

is the pressure at the point at which pressure coefficient is being evaluated is the pressure in the freestream (i.e. remote from any disturbance)

is the pressure in the freestream (i.e. remote from any disturbance) is the freestream fluid density (Air at sea level and 15 °C is 1.225

is the freestream fluid density (Air at sea level and 15 °C is 1.225  )

) is the freestream velocity of the fluid, or the velocity of the body through the fluid

is the freestream velocity of the fluid, or the velocity of the body through the fluid

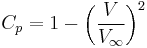

Using Bernoulli's Equation, the pressure coefficient can be further simplified for incompressible, lossless, and steady flow[3]:

where V is the velocity of the fluid at the point at which pressure coefficient is being evaluated.

This relationship is also valid for the flow of compressible fluids where variations in speed and pressure are sufficiently small that variations in fluid density can be ignored. This is a reasonable assumption when the Mach Number is less than about 0.3.

of zero indicates the pressure is the same as the free stream pressure.

of zero indicates the pressure is the same as the free stream pressure. of one indicates the pressure is stagnation pressure and the point is a stagnation point.

of one indicates the pressure is stagnation pressure and the point is a stagnation point. of minus one is significant in the design of gliders because this indicates a perfect location for a "Total energy" port for supply of signal pressure to the Variometer, a special Vertical Speed Indicator which reacts to vertical movements of the atmosphere but does not react to vertical maneuvering of the glider.

of minus one is significant in the design of gliders because this indicates a perfect location for a "Total energy" port for supply of signal pressure to the Variometer, a special Vertical Speed Indicator which reacts to vertical movements of the atmosphere but does not react to vertical maneuvering of the glider.

In the fluid flow field around a body there will be points having positive pressure coefficients up to one, and negative pressure coefficients including coefficients less than minus one, but nowhere will the coefficient exceed plus one because the highest pressure that can be achieved is the stagnation pressure. The only time the coefficient will exceed plus one is when advanced boundary layer control techniques, such as blowing, is used.

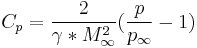

Compressible flow

In the flow of compressible fluids such as air, and particularly the high-speed flow of compressible fluids,  (the dynamic pressure) is no longer an accurate measure of the difference between stagnation pressure and static pressure. Also, the familiar relationship that stagnation pressure is equal to total pressure does not always hold true. (It is always true in isentropic flow but the presence of shock waves can cause the flow to depart from isentropic.) As a result, pressure coefficients can be greater than one in compressible flow.

(the dynamic pressure) is no longer an accurate measure of the difference between stagnation pressure and static pressure. Also, the familiar relationship that stagnation pressure is equal to total pressure does not always hold true. (It is always true in isentropic flow but the presence of shock waves can cause the flow to depart from isentropic.) As a result, pressure coefficients can be greater than one in compressible flow.

greater than one indicates the freestream flow is compressible.

greater than one indicates the freestream flow is compressible.

Pressure distribution

An airfoil at a given angle of attack will have what is called a pressure distribution. This pressure distribution is simply the pressure at all points around an airfoil. Typically, graphs of these distributions are drawn so that negative numbers are higher on the graph, as the  for the upper surface of the airfoil will usually be farther below zero and will hence be the top line on the graph.

for the upper surface of the airfoil will usually be farther below zero and will hence be the top line on the graph.

and

and  relationship

relationship

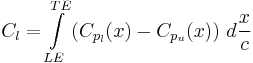

The coefficient of lift for an airfoil with strictly horizontal surfaces can be calculated from the coefficient of pressure distribution by integration, or calculating the area between the lines on the distribution. This expression is not suitable for direct numeric integration using the panel method of lift approximation, as it does not take into account the direction of pressure-induced lift.

where:

is pressure coefficient on the lower surface

is pressure coefficient on the lower surface is pressure coefficient on the upper surface

is pressure coefficient on the upper surface is the leading edge

is the leading edge is the trailing edge

is the trailing edge

When the lower surface  is higher (more negative) on the distribution it counts as a negative area as this will be producing down force rather than lift.

is higher (more negative) on the distribution it counts as a negative area as this will be producing down force rather than lift.

See also

References

- Clancy, L.J. (1975) Aerodynamics, Pitman Publishing Limited, London. ISBN 0 273 01120 0

- Abbott, I.H. and Von Doenhoff, A.E. (1959) Theory of Wing Sections, Dover Publications, Inc. New York, Standard Book No. 486-60586-8

- Anderson, John D (2001) Fundamentals of Aerodynamic 3rd Edition, McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0 07 237335 0