Polar curve

In algebraic geometry, the first polar, or simply polar of an algebraic plane curve C of degree n with respect to a point Q is an algebraic curve of degree n−1 which contains every point of C whose tangent line passes through Q. It is used to investigate the relationship between the curve and its dual, for example in the derivation of the Plücker formulas.

Contents |

Definition

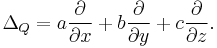

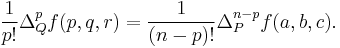

Let C be defined in homogeneous coordinates by f(x, y, z) = 0 where f is a homogeneous polynomial of degree n, and let the homogeneous coordinates of Q be (a, b, c). Define the operator

Then ΔQf is a homogeneous polynomial of degree n−1 and ΔQf(x, y, z) = 0 defines a curve of degree n−1 called the first polar of C with respect of Q.

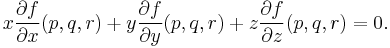

If P=(p, q, r) is a non-singular point on the curve C then the equation of the tangent at P is

In particular, if P is on the intersection of C and its first polar with respect to Q if and only if Q is on the tangent to C at P. Note also that for a double point of C, the partial derivatives of f are all 0 so the first polar contains these points as well.

Class of a curve

The class of C may be defined as the number of tangents that may be drawn to C from a point not on C (counting multiplicities and including imaginary tangents). Each of these tangents touches C at one of the points of intersection of C and the first polar, and by Bézout's theorem theorem there are at most n(n−1) of these. This puts an upper bound of n(n−1) on the class of a curve of degree n. The class may be computed exactly by counting the number and type of singular points on C (see Plücker formula).

Higher polars

The p-th polar of a C for an natural number p is defined as ΔQpf(x, y, z) = 0. This is a curve of degree n−p. When p is n−1 the p-th polar is a line called the polar line of C with respect to Q. Similarly, when p is n−2 the curve is called the polar conic of C.

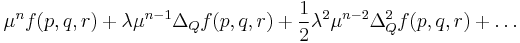

Using Taylor series in several variables and exploiting homogeneity, f(λa+μp, λb+μq, λc+μr) can be expanded in two ways as

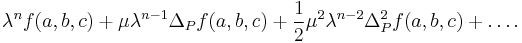

and

Comparing coefficients of λpμn−p shows that

In particular, the p-th polar of C with respect to Q is the locus of points P so that the (n−p)-th polar of C with respect to P passes through Q.[1]

Poles

If the polar line of C with respect to a point Q is a line L, the Q is said to be a pole of L. A given line has (n−1)2 poles (counting multiplicities etc.) where n is the degree of C. So see this, pick two points P and Q on L. The locus of points whose polar lines pass through P is the first polar of P and this is a curve of degree n−1. Similarly, the locus of points whose polar lines pass through Q is the first polar of Q and this is also a curve of degree n−1. The polar line of a point is L if and only if it contains both P and Q, so the poles of L are exactly the points of intersection of the two first polars. By Bézout's theorem these curves have (n−1)2 points of intersection and these are the pole of L.[2]

The Hessian

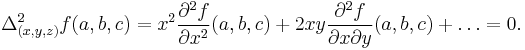

For a given point Q=(a, b, c), the polar conic is the locus of points P so that Q is on the second polar of P. In other words the equation of the polar conic is

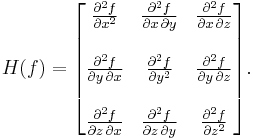

The conic is degenerate if and only if the determinant of the Hessian of f,

Therefor the equation |H(f)|=0 defines a curve, the locus of points whose polar conics are degenerate, of degree 3(n−2) called the Hessian curve of C.

See also

References

- Basset, Alfred Barnard (1901). An Elementary Treatise on Cubic and Quartic Curves. Deighton Bell & Co.. pp. 16ff.. http://books.google.com/books?id=yUxtAAAAMAAJ.

- Salmon, George (1879). Higher Plane Curves. Hodges, Foster, and Figgis. pp. 49ff.. http://www.archive.org/details/treatiseonhigher00salmuoft.

- Section 1.2 of Fulton, Introduction to intersection theory in algebraic geometry, CBMS, AMS, 1984.

- Ivanov, A.B. (2001), "Polar", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=P/p073400

- Ivanov, A.B. (2001), "Hessian (algebraic curve)", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=H/h047150