Lattice gauge theory

| Quantum field theory |

|---|

| History of... |

|

Incomplete theories

|

|

Scientists

Adler • Bethe • Bogoliubov • Callan • Candlin • Coleman • DeWitt • Dirac • Dyson • Fermi • Feynman • Fierz • Fröhlich • Gell-Mann • Goldstone • Gross • 't Hooft • Jackiw • Klein • Landau • Lee • Lehmann • Majorana • Nambu • Parisi • Polyakov • Salam • Schwinger • Skyrme • Stueckelberg • Symanzik • Tomonaga • Veltman • Weinberg • Weisskopf • Wilson • Witten • Yang • Yukawa • Hoodbhoy • Zimmermann • Zinn-Justin

|

In physics, lattice gauge theory is the study of gauge theories on a spacetime that has been discretized into a lattice. Gauge theories are important in particle physics, and include the prevailing theories of elementary particles: quantum electrodynamics, quantum chromodynamics (QCD) and the Standard Model. Non-perturbative gauge theory calculations in continuous spacetime formally involve evaluating an infinite-dimensional path integral, which is computationally intractable. By working on a discrete spacetime, the path integral becomes finite-dimensional, and can be evaluated by stochastic simulation techniques such as the Monte Carlo method. When the size of the lattice is taken infinitely large and its sites infinitesimally close to each other, the continuum gauge theory is recovered intuitively. A mathematical proof of this fact is lacking.

Contents |

Basics

In lattice gauge theory, the spacetime is Wick rotated into Euclidean space and discretized into a lattice with sites separated by distance  and connected by links. In the most commonly-considered cases, such as lattice QCD, fermion fields are defined at lattice sites (which leads to fermion doubling), while the gauge fields are defined on the links. That is, an element U of the compact Lie group G is assigned to each link. Hence to simulate QCD, with Lie group SU(3), there is a 3×3 special unitary matrix defined on each link. The link is assigned an orientation, with the inverse element corresponding to the same link with the opposite orientation.

and connected by links. In the most commonly-considered cases, such as lattice QCD, fermion fields are defined at lattice sites (which leads to fermion doubling), while the gauge fields are defined on the links. That is, an element U of the compact Lie group G is assigned to each link. Hence to simulate QCD, with Lie group SU(3), there is a 3×3 special unitary matrix defined on each link. The link is assigned an orientation, with the inverse element corresponding to the same link with the opposite orientation.

Yang–Mills action

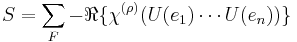

The Yang–Mills action is written on the lattice using Wilson loops (named after Kenneth G. Wilson), so that the limit  formally reproduces the original continuum action.[1] Given a faithful irreducible representation ρ of G, the lattice Yang-Mills action is the sum over all lattice sites of the (real component of the) trace over the n links e1, ..., en in the Wilson loop,

formally reproduces the original continuum action.[1] Given a faithful irreducible representation ρ of G, the lattice Yang-Mills action is the sum over all lattice sites of the (real component of the) trace over the n links e1, ..., en in the Wilson loop,

Here, χ is the character. If ρ is a real (or pseudoreal) representation, taking the real component is redundant, because even if the orientation of a Wilson loop is flipped, its contribution to the action remains unchanged.

There are many possible lattice Yang-Mills actions, depending on which Wilson loops are used in the action. The simplest "Wilson action" uses only the 1×1 Wilson loop, and differs from the continuum action by "lattice artifacts" proportional to the small lattice spacing  . By using more complicated Wilson loops to construct "improved actions", lattice artifacts can be reduced to be proportional to

. By using more complicated Wilson loops to construct "improved actions", lattice artifacts can be reduced to be proportional to  , making computations more accurate.

, making computations more accurate.

Measurements and calculations

Quantities such as particle masses are stochastically calculated using techniques such as the Monte Carlo method. Gauge field configurations are generated with probabilities proportional to  , where

, where  is the lattice action and

is the lattice action and  is related to the lattice spacing

is related to the lattice spacing  . The quantity of interest is calculated for each configuration, and averaged. Calculations are often repeated at different lattice spacings

. The quantity of interest is calculated for each configuration, and averaged. Calculations are often repeated at different lattice spacings  so that the result can be extrapolated to the continuum,

so that the result can be extrapolated to the continuum,  .

.

Such calculations are often extremely computationally intensive, and can require the use of the largest available supercomputers. To reduce the computational burden, the so-called quenched approximation can be used, in which the fermionic fields are treated as non-dynamic "frozen" variables. While this was common in early lattice QCD calculations, "dynamical" fermions are now standard.[3] These simulations typically utilize algorithms based upon molecular dynamics or microcanonical ensemble algorithms.[4][5]

The results of lattice QCD computations show e.g. that in a meson not only the particles (quarks and antiquarks), but also the "fluxtubes" of the gluon fields are important.

Other applications

Originally, solvable two-dimensional lattice gauge theories had already been introduced in 1971 as models with interesting statistical properties by the theorist Franz Wegner, who worked in the field of phase transitions.[6]

Lattice gauge theory has been shown to be exactly dual to spin foam models provided that only 1×1 Wilson loops appear in the action.

See also

Further reading

- M. Creutz, Quarks, gluons and lattices, Cambridge University Press 1985.

- I. Montvay and G. Münster, Quantum Fields on a Lattice, Cambridge University Press 1997.

- Y. Makeenko, Methods of contemporary gauge theory, Cambridge University Press 2002, ISBN 0-521-80911-8.

- J. Smit, Introduction to Quantum Fields on a Lattice, Cambridge University Press 2002.

- H. Rothe, Lattice Gauge Theories, An Introduction, World Scientific 2005.

- T. DeGrand and C. DeTar, Lattice Methods for Quantum Chromodynamics, World Scientific 2006.

- C. Gattringer and C. B. Lang, Quantum Chromodynamics on the Lattice, Springer 2010.

External links

References

- ^ Wilson, K. (1974). "Confinement of quarks". Physical Review D 10 (8): 2445. Bibcode 1974PhRvD..10.2445W. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.10.2445.

- ^ M. Cardoso et al., Lattice QCD computation of the colour fields for the static hybrid quark-gluon-antiquark system, and microscopic study of the Casimir scaling, Phys. Rev. D 81, 034504 (2010) ).

- ^ A. Bazavov et al. (2010). "Nonperturbative QCD simulations with 2+1 flavors of improved staggered quarks". Reviews of Modern Physics 82 (2): 1349–1417. arXiv:0903.3598. Bibcode 2010RvMP...82.1349B. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.82.1349.

- ^ David J. E. Callaway and Aneesur Rahman (1982). "Microcanonical Ensemble Formulation of Lattice Gauge Theory". Physical Review Letters 49 (9): 613–616. Bibcode 1982PhRvL..49..613C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.49.613.

- ^ David J. E. Callaway and Aneesur Rahman (1983). "Lattice gauge theory in the microcanonical ensemble". Physical Review D28 (6): 1506–1514. Bibcode 1983PhRvD..28.1506C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.28.1506.

- ^ F. Wegner, "Duality in Generalized Ising Models and Phase Transitions without Local Order Parameter", J. Math. Phys. 12 (1971) 2259-2272. Reprinted in Claudio Rebbi (ed.), Lattice Gauge Theories and Monte-Carlo-Simulations, World Scientific, Singapore (1983), p. 60-73. Abstract