Plücker coordinates

In geometry, Plücker coordinates, introduced by Julius Plücker in the 19th century, are a way to assign six homogenous coordinates to each line in projective 3-space, P3. Because they satisfy a quadratic constraint, they establish a one-to-one correspondence between the 4-dimensional space of lines in P3 and points on a quadric in P5 (projective 5-space). A predecessor and special case of Grassmann coordinates (which describe k-dimensional linear subspaces, or flats, in an n-dimensional Euclidean space), Plücker coordinates arise naturally in geometric algebra. They have proved useful for computer graphics, and also can be extended to coordinates for the screws and wrenches in the theory of kinematics used for robot control.

Contents |

Geometric intuition

A line L in 3-dimensional Euclidean space is determined by two distinct points that it contains, or by two distinct planes that contain it. Consider the first case, with points x = (x1,x2,x3) and y = (y1,y2,y3). The vector displacement from x to y is nonzero because the points are distinct, and represents the direction of the line. That is, every displacement between points on L is a scalar multiple of d = y−x. If a physical particle of unit mass were to move from x to y, it would have a moment about the origin. The geometric equivalent is a vector whose direction is perpendicular to the plane containing L and the origin, and whose length equals twice the area of the triangle formed by the displacement and the origin. Treating the points as displacements from the origin, the moment is m = x×y, where "×" denotes the vector cross product. The area of the triangle is proportional to the length of the segment between x and y, considered as the base of the triangle; it is not changed by sliding the base along the line, parallel to itself. By definition the moment vector is perpendicular to every displacement along the line, so d•m = 0, where "•" denotes the vector dot product.

Although neither d nor m alone is sufficient to determine L, together the pair does so uniquely, up to a common (nonzero) scalar multiple which depends on the distance between x and y. That is, the coordinates

- (d:m) = (d1:d2:d3:m1:m2:m3)

may be considered homogeneous coordinates for L, in the sense that all pairs (λd:λm), for λ ≠ 0, can be produced by points on L and only L, and any such pair determines a unique line so long as d is not zero and d•m = 0. Furthermore, this approach extends to include points, lines, and a plane "at infinity", in the sense of projective geometry.

- Example. Let x = (2,3,7) and y = (2,1,0). Then (d:m) = (0:−2:−7:−7:14:−4).

Alternatively, let the equations for points x of two distinct planes containing L be

- 0 = a + a•x

- 0 = b + b•x .

Then their respective planes are perpendicular to vectors a and b, and the direction of L must be perpendicular to both. Hence we may set d = a×b, which is nonzero because a and b are neither zero nor parallel (the planes being distinct and intersecting). If point x satisfies both plane equations, then it also satisfies the linear combination

-

0 = a (b + b•x) − b (a + a•x) = (a b − b a)•x .

That is, m = a b − b a is a vector perpendicular to displacements to points on L from the origin; it is, in fact, a moment consistent with the d previously defined from a and b.

- Example. Let a0 = 2, a = (−1,0,0) and b0 = −7, b = (0,7,−2). Then (d:m) = (0:−2:−7:−7:14:−4).

Although the usual algebraic definition tends to obscure the relationship, (d:m) are the Plücker coordinates of L.

Algebraic definition

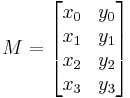

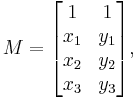

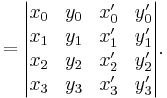

In a 3-dimensional projective space, P3, let L be a line containing distinct points x and y with homogeneous coordinates (x0:x1:x2:x3) and (y0:y1:y2:y3), respectively. Let M be the 4×2 matrix with these coordinates as columns.

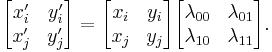

Because x and y are distinct points, the columns of M are linearly independent; M has rank 2. Let M′ be a second matrix, with columns x′ and y′ a different pair of distinct points on L. Then the columns of M′ are linear combinations of the columns of M; so for some 2×2 nonsingular matrix Λ,

In particular, rows i and j of M′ and M are related by

Therefore, the determinant of the left side 2×2 matrix equals the product of the determinants of the right side 2×2 matrices, the latter of which is a fixed scalar, det Λ.

Primary coordinates

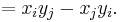

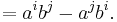

With this motivation, we define Plücker coordinate pij as the determinant of rows i and j of M,

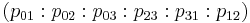

This implies pii = 0 and pij = −pji, reducing the possibilities to only six (4 choose 2) independent quantities. As we have seen, the sixtuple

is uniquely determined by L, up to a common nonzero scale factor. Furthermore, all six components cannot be zero, because if they were, all 2×2 subdeterminants in M would be zero and the rank of M at most one, contradicting the assumption that x and y are distinct. Thus the Plücker coordinates of L, as suggested by the colons, may be considered homogeneous coordinates of a point in a 5-dimensional projective space.

Plücker map

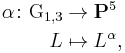

Denote the set of all lines (linear images of P1) in P3 by G1,3. We thus have a map:

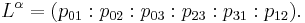

where

Dual coordinates

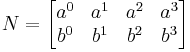

Alternatively, let L be a line contained in distinct planes a and b with homogeneous coefficients (a0:a1:a2:a3) and (b0:b1:b2:b3), respectively. (The first plane equation is 0 = ∑k akxk, for example.) Let N be the 2×4 matrix with these coordinates as rows.

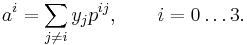

We define dual Plücker coordinate pij as the determinant of columns i and j of N,

Dual coordinates are convenient in some computations, and we can show that they are equivalent to primary coordinates. Specifically, let (i,j,k,l) be an even permutation of (0,1,2,3); then

Geometry

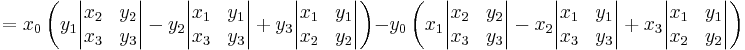

To relate back to the geometric intuition, take x0 = 0 as the plane at infinity; thus the coordinates of points not at infinity can be normalized so that x0 = 1. Then M becomes

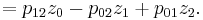

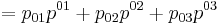

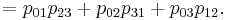

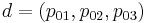

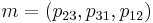

and setting x = (x1,x2,x3) and y = (y1,y2,y3), we have d = (p01,p02,p03) and m = (p23,p31,p12).

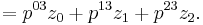

Dually, we have d = (p23,p31,p12) and m = (p01,p02,p03).

Bijection between lines and Klein quadric

Plane equations

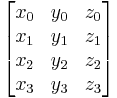

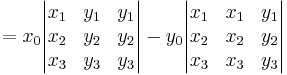

If the point z = (z0:z1:z2:z3) lies on L, then the columns of

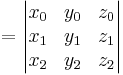

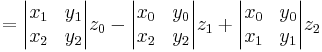

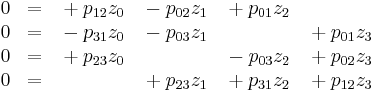

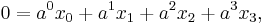

are linearly dependent, so that the rank of this larger matrix is still 2. This implies that all 3×3 submatrices have determinant zero, generating four (4 choose 3) plane equations, such as

The four possible planes obtained are as follows.

Using dual coordinates, and letting (a0:a1:a2:a3) be the line coefficients, each of these is simply ai = pij, or

Each Plücker coordinate appears in two of the four equations, each time multiplying a different variable; and as at least one of the coordinates is nonzero, we are guaranteed non-vacuous equations for two distinct planes intersecting in L. Thus the Plücker coordinates of a line determine that line uniquely, and the map α is an injection.

Quadratic relation

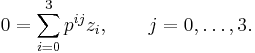

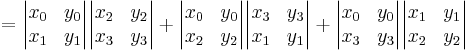

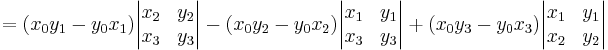

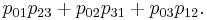

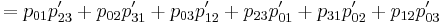

The image of α is not the complete set of points in P5; the Plücker coordinates of a line L satisfy the quadratic Plücker relation

For proof, write this homogeneous polynomial as determinants and use Laplace expansion (in reverse).

Since both 3×3 determinants have duplicate columns, the right hand side is identically zero.

Another proof may be done like this: Since vector

is perpendicular to vector

(see above), the scalar product of d and m must be zero! q.e.d.

Point equations

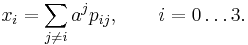

Letting (x0:x1:x2:x3) be the point coordinates, four possible points on a line each have coordinates xi = pij, for j = 0…3. Some of these possible points may be inadmissible because all coordinates are zero, but since at least one Plücker coordinate is nonzero, at least two distinct points are guaranteed.

Bijectivity

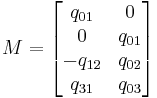

If (q01:q02:q03:q23:q31:q12) are the homogeneous coordinates of a point in P5, without loss of generality assume that q01 is nonzero. Then the matrix

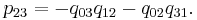

has rank 2, and so its columns are distinct points defining a line L. When the P5 coordinates, qij, satisfy the quadratic Plücker relation, they are the Plücker coordinates of L. To see this, first normalize q01 to 1. Then we immediately have that for the Plücker coordinates computed from M, pij = qij, except for

But if the qij satisfy the Plücker relation q23+q02q31+q03q12 = 0, then p23 = q23, completing the set of identities.

Consequently, α is a surjection onto the algebraic variety consisting of the set of zeros of the quadratic polynomial

And since α is also an injection, the lines in P3 are thus in bijective correspondence with the points of this quadric in P5, called the Plücker quadric or Klein quadric.

Uses

Plücker coordinates allow concise solutions to problems of line geometry in 3-dimensional space, especially those involving incidence.

Line-line crossing

Two lines in P3 are either skew or coplanar, and in the latter case they are either coincident or intersect in a unique point. If pij and p′ij are the Plücker coordinates of two lines, then they are coplanar precisely when d⋅m′+m⋅d′ = 0, as shown by

When the lines are skew, the sign of the result indicates the sense of crossing: positive if a right-handed screw takes L into L′, else negative.

The quadratic Plücker relation essentially states that a line is coplanar with itself.

Line-line join

In the event that two lines are coplanar but not parallel, their common plane has equation

- 0 = (m•d′)x0 + (d×d′)•x ,

where x = (x1,x2,x3).

The slightest perturbation will destroy the existence of a common plane, and near-parallelism of the lines will cause numeric difficulties in finding such a plane even if it does exist.

Line-line meet

Dually, two coplanar lines, neither of which contains the origin, have common point

- (x0 : x) = (d•m′:m×m′) .

To handle lines not meeting this restriction, see the references.

Plane-line meet

Given a plane with equation

or more concisely 0 = a0x0+a•x; and given a line not in it with Plücker coordinates (d:m), then their point of intersection is

- (x0 : x) = (a•d : a×m − a0d) .

The point coordinates, (x0:x1:x2:x3), can also be expressed in terms of Plücker coordinates as

Point-line join

Dually, given a point (y0:y) and a line not containing it, their common plane has equation

- 0 = (y•m) x0 + (y×d−y0m)•x .

The plane coordinates, (a0:a1:a2:a3), can also be expressed in terms of dual Plücker coordinates as

Line families

Because the Klein quadric is in P5, it contains linear subspaces of dimensions one and two (but no higher). These correspond to one- and two-parameter families of lines in P3.

For example, suppose L and L′ are distinct lines in P3 determined by points x, y and x′, y′, respectively. Linear combinations of their determining points give linear combinations of their Plücker coordinates, generating a one-parameter family of lines containing L and L′. This corresponds to a one-dimensional linear subspace belonging to the Klein quadric.

Lines in plane

If three distinct and non-parallel lines are coplanar; their linear combinations generate a two-parameter family of lines, all the lines in the plane. This corresponds to a two-dimensional linear subspace belonging to the Klein quadric.

Lines through point

If three distinct and non-coplanar lines intersect in a point, their linear combinations generate a two-parameter family of lines, all the lines through the point. This also corresponds to a two-dimensional linear subspace belonging to the Klein quadric.

Ruled surface

A ruled surface is a family of lines that is not necessarily linear. It corresponds to a curve on the Klein quadric. For example, a hyperboloid of one sheet is a quadric surface in P3 ruled by two different families of lines, one line of each passing through each point of the surface; each family corresponds under the Plücker map to a conic section within the Klein quadric in P5.

Line geometry

During the nineteenth century, line geometry was studied intensively. In terms of the bijection given above, this is a description of the intrinsic geometry of the Klein quadric.

Ray tracing

Line geometry is extensively used in ray tracing application where the geometry and intersections of rays need to be calculated in 3D. An implementation is described in Introduction to Pluecker Coordinates written for the Ray Tracing forum by Thouis Jones.

See also

References

- Hodge, W. V. D.; D. Pedoe (1994) [1947]. Methods of Algebraic Geometry, Volume I (Book II). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-46900-5.

- Behnke, H.; F. Bachmann, K. Fladt, H. Kunle (eds.) (1984). Fundamentals of Mathematics, Volume II: Geometry. trans. S. H. Gould. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-52094-2.

From the German: Grundzüge der Mathematik, Band II: Geometrie. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. - Kuptsov, L.P. (2001), "Plücker coordinates", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=P/p072890

- Mason, Matthew T.; J. Kenneth Salisbury (1985). Robot Hands and the Mechanics of Manipulation. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-13205-3.

- Hohmeyer, M.; S. Teller (1999). "Determining the Lines Through Four Lines" (PDF). Journal of Graphics Tools (A K Peters) 4 (3): 11–22. ISSN 1086-7651. http://people.csail.mit.edu/seth/pubs/TellerHohmeyerJGT2000.pdf.