Phase detector

A phase detector or phase comparator is a frequency mixer, analog multiplier or logic circuit that generates a voltage signal which represents the difference in phase between two signal inputs. It is an essential element of the phase-locked loop (PLL).

Detecting phase differences is very important in many applications, such as motor control, radar and telecommunication systems, servo mechanisms, and demodulators.

Contents |

Types

Phase detectors for phase-locked loop circuits may be classified in two types.[1] A Type I detector is designed to be driven by analog signals or square-wave digital signals and produces an output pulse at the difference frequency. The Type I detector always produces an output waveform, which must be filtered to control the phase-locked loop voltage-controlled oscillator (VCO). A type II detector is sensitive only to the relative timing of the edges of the input and reference pulses, and produces a constant output proportional to phase difference when both signals are at the same frequency. This output will tend not to produce ripple in the control voltage of the VCO.

Analog phase detector

The phase detector needs to compute the phase difference of its two input signals. Let α be the phase of the first input and β be the phase of the second. The actual input signals to the phase detector, however, are not α and β, but rather sinusoids such as sin(α) and cos(β). In general, computing the phase difference would involve computing the arcsine and arccosine of each normalized input (to get an ever increasing phase) and doing a subtraction. Such an analog calculation is difficult. Fortunately, the calculation can be simplified by using some approximations.

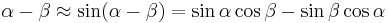

Assume that the phase differences will be small (much less than 1 radian, for example). The small-angle approximation for the sine function and the sine angle addition formula yield:

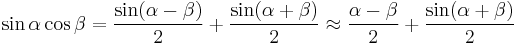

The expression suggests a quadrature phase detector can be made by summing the outputs of two multipliers. The quadrature signals may be formed with phase shift networks. Two common implementations for multipliers are the double balanced diode mixer (diode ring) and the four-quadrant multiplier (Gilbert cell).

Instead of using two multipliers, a more common phase detector uses a single multiplier and a different trigonometric identity:

The first term provides the desired phase difference. The second term is a sinusoid at twice the reference frequency, so it can be filtered out. In the case of general waveforms the phase detector output is described with phase detector characteristic

A mixer-based detector (e.g., a Schottky diode-based double-balanced mixer) provides "the ultimate in phase noise floor performance" and "in system sensitivity." since it does not create finite pulse widths at the phase detector output.[2] Another advantage of a mixer-based PD is its relative simplicity.[2] Both the quadrature and simple multiplier phase detectors have an output that depends on the input amplitudes as well as the phase difference. In practice, the input amplitudes are normalized.

Digital phase detector

A phase detector suitable for square wave signals can be made from an exclusive-OR (XOR) logic gate. When the two signals being compared are completely in-phase, the XOR gate's output will have a constant level of zero. When the two signals differ in phase by 1°, the XOR gate's output will be high for 1/180th of each cycle — the fraction of a cycle during which the two signals differ in value. When the signals differ by 180° — that is, one signal is high when the other is low, and vice versa — the XOR gate's output remains high throughout each cycle.

The XOR detector compares well to the analog mixer in that it locks near a 90° phase difference and has a square-wave output at twice the reference frequency. The square-wave changes duty-cycle in proportion to the phase difference resulting. Applying the XOR gate's output to a low-pass filter results in an analog voltage that is proportional to the phase difference between the two signals. It requires inputs that are symmetrical square waves, or nearly so. The remainder of its characteristics are very similar to the analog mixer for capture range, lock time, reference spurious and low-pass filter requirements.

Digital phase detectors can also be based on a sample and hold circuit, a charge pump, or a logic circuit consisting of flip-flops (see figure). When a phase detector that's based on logic gates is used in a PLL, it can quickly force the VCO to synchronize with an input signal, even when the frequency of the input signal differs substantially from the initial frequency of the VCO. Such phase detectors also have other desirable properties, such as better accuracy when there are only small phase differences between the two signals being compared. This is because a digital phase detector has a nearly infinite pull-in range in comparison to an XOR detector.

Phase-frequency detector

A phase-frequency detector is an asynchronous sequential logic circuit originally made of four flip-flops (e.g., the phase-frequency detectors found in both the RCA CD4046 and the motorola MC4344 ICs introduced in the 1970s). The logic determines which of the two signals has a zero-crossing earlier or more often. When used in a PLL application, lock can be achieved even when it is off frequency and is known as a Phase Frequency Detector. Such a detector has the advantage of producing an output even when the two signals being compared differ not only in phase but in frequency. A phase frequency detector prevents a "false lock" condition in PLL applications, in which the PLL synchronizes with the wrong phase of the input signal or with the wrong frequency (e.g., a harmonic of the input signal).[3]

A bang-bang charge pump phase detector supplies current pulses with fixed total charge, either positive or negative, to the capacitor acting as an integrator. A phase detector for a bang-bang charge pump must always have a dead band where the phases of inputs are close enough that the detector fires either both or neither of the charge pumps, for no total effect. Bang-bang phase detectors are simple, but are associated with significant minimum peak-to-peak jitter, because of drift within the dead band.

In 1976 it was shown that by using a three-state phase detector configuration (using only two flip-flops) instead of the original RCA/Motorola twelve-state configurations, this problem could be elegantly overcome. For other types of phase-frequency detectors other, though possibly less-elegant, solutions exist to the dead zone phenomenon.[3] Other solutions are necessary since the three-state phase-frequency detector does not work for certain applications involving randomized signal degradation, which can be found on the inputs to some signal regeneration systems (e.g., clock recovery designs).[4]

A proportional phase detector employs a charge pump that supplies charge amounts in proportion to the phase error detected. Some have dead bands and some do not. Specifically, some designs produce both "up" and "down" control pulses even when the phase difference is zero. These pulses are small, nominally the same duration, and cause the charge pump to produce equal-charge positive and negative current pulses when the phase is perfectly matched. Phase detectors with this kind of control system don't exhibit a dead band and typically have lower minimum peak-to-peak jitter when used in PLLs.

In PLL applications it is frequently required to know when the loop is out of lock. The more complex digital phase-frequency detectors usually have an output that allows a reliable indication of an out of lock condition.

Electronic phase detector

Some signal processing techniques such as those used in radar may require both the amplitude and the phase of a signal, to recover all the information encoded in that signal. One technique is to feed an amplitude-limited signal into one port of a product detector and a reference signal into the other port; the output of the detector will represent the phase difference between the signals. If the signal is different in frequency from the reference, the detector output will be periodic at the difference frequency.[5]

Optical phase detectors

Phase detectors are also known in optics as interferometers. For pulsed (amplitude modulated) light, it is said to measure the phase between the carriers. It is also possible to measure the delay between the envelopes of two short optical pulses by means of cross correlation in a nonlinear crystal. And it is possible to measure the phase between the envelope and the carrier of an optical pulse, by sending a pulse into an nonlinear crystal. There the spectrum gets wider and at the edges the shape depends significantly on the phase.

See also

References

- ^ Paul Horowitz and Winfield Hill, The Art of Electronics 2nd Ed. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1989 ISBN 0-521370957 pg. 644

- ^ a b Crawford, 1994, p. 9, 19

- ^ a b Crawford, 1994, p. 17-23, 153, and several other pages

- ^ Wolaver, 1991, p.211

- ^ Donald G. Fink (ed), Electronic Engineers Handbook, McGraw Hill, New York 1975, ISBN 0-07-02980-4 pg. 25-76

- Crawford, James A. 1994. Frequency Synthesizer Design Handbook, Artech House, ISBN 0-89006-440-7

- Wolaver, Dan H. 1991. Phase-Locked Loop Circuit Design, Prentice Hall, ISBN 0-13-662743-9

Further reading

- Egan, William F. 2000. Frequency Synthesis by Phase-lock, 2nd Ed., John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0-471-32104-4