Bracket

Brackets are tall punctuation marks used in matched pairs within text, to set apart or interject other text. In the United States, "bracket" usually refers specifically to the "square" or "box" type.[1][2]

Contents |

List of types

- ( ) — round brackets, open brackets, brackets (UK), or parentheses

- [ ] — square brackets, closed brackets, or brackets (US)

- { } — curly brackets, definite brackets, swirly brackets, curly braces, birdie brackets, Scottish brackets, squirrelly brackets, braces, gullwings, fancy brackets, or squiggly brackets

- ⟨ ⟩ — angle brackets, triangular brackets, diamond brackets, tuples, or chevrons

- < > — inequality signs, or brackets. Sometimes referred to as angle brackets, in such cases as HTML markup. Occasionally known as broken brackets or brokets.[3]

- ‹ ›; « » — angular quote brackets, or guillemets

- ⸤ ⸥; 「 」 — corner brackets

History

The chevron was the earliest type to appear in written English. Desiderius Erasmus coined the term lunula to refer to the rounded parentheses (), recalling the round shape of the moon.[4]

Usage

In addition to referring to the class of all types of brackets, the unqualified word bracket is most commonly used to refer to a specific type of bracket. In modern American usage this is usually the square bracket.

In American usage, parentheses are usually considered separate from other brackets, and calling them "brackets" at all is unusual even though they serve a similar function. In more formal usage "parenthesis" may refer to the entire bracketed text, not just to the punctuation marks used (so all the text in this set of round brackets may be said to be a parenthesis or a parenthetical).[5]

According to early typographic practice, brackets are never set in italics, even when the surrounding characters are italic.[6]

Types

Parentheses ( )

Parentheses (singular, parenthesis) – also called simply brackets, or round brackets, curved brackets, oval brackets, or, colloquially, parens – contain material that could be omitted without destroying or altering the meaning of a sentence. In most writing, overuse of parentheses is usually a sign of a badly structured text. A milder effect may be obtained by using a pair of commas as the delimiter, though if the sentence contains commas for other purposes visual confusion may result.

Parentheses may be used in formal writing to add supplementary information, such as "Sen. John McCain (R., Arizona) spoke at length." They can also indicate shorthand for "either singular or plural" for nouns – e.g., "the claim(s)" – or for "either masculine or feminine" in some languages with grammatical gender.[7]

Parenthetical phrases have been used extensively in informal writing and stream of consciousness literature. Of particular note is the southern American author William Faulkner (see Absalom, Absalom! and the Quentin section of The Sound and the Fury) as well as poet E. E. Cummings. Parentheses have historically been used where the dash is currently used – that is, in order to depict alternatives, such as "parenthesis)(parentheses". Examples of this usage can be seen in editions of Fowler's.

Parentheses may also be nested (generally with one set (such as this) inside another set). This is not commonly used in formal writing (though sometimes other brackets [especially square brackets] will be used for one or more inner set of parentheses [in other words, secondary {or even tertiary} phrases can be found within the main parenthetical sentence]).[8]

Any punctuation inside parentheses or other brackets is independent of the rest of the text: "Mrs. Pennyfarthing (What? Yes, that was her name!) was my landlady." In this usage the explanatory text in the parentheses is a parenthesis. (Parenthesized text is usually short and within a single sentence. Where several sentences of supplemental material are used in parentheses the final full stop would be within the parentheses. Again, the parenthesis implies that the meaning and flow of the text is supplemental to the rest of the text and the whole would be unchanged were the parenthesized sentences removed.)

Parentheses in mathematics signify a different precedence of operators. Normally, 2 + 3 × 4 would be 14, since the multiplication is done before the addition. On the other hand (2 + 3) × 4 is 20, because the parentheses override normal precedence, causing the addition to be done first. Some authors follow the convention in mathematical equations that, when parentheses have one level of nesting, the inner pair are parentheses and the outer pair are square brackets. Example:

A related convention is that when parentheses have two levels of nesting, braces are the outermost pair.

Parentheses are also used to set apart the arguments in mathematical functions. For example, f(x) is the function f applied to the variable x. In coordinate systems parentheses are used to denote a set of coordinates; so in the Cartesian coordinate system (4, 7) may represent the point located at 4 on the x-axis and 7 on the y-axis. Parentheses may also represent intervals; (0, 5), for example, is the interval between 0 and 5, not including 0 or 5.

Parentheses may also be used to represent a binomial coefficient, and in chemistry to denote a polyatomic ion.

In Chinese and Japanese, 【 】, a combination of brackets and parentheses called 方頭括號 and sumitsuki, are used for inference in Chinese and used in titles and headings in Japanese.

Square brackets [ ]

Square brackets – also called simply brackets (US) – are mainly used to enclose explanatory or missing material usually added by someone other than the original author, especially in quoted text.[9] Examples include: "I appreciate it [the honor], but I must refuse", and "the future of psionics [see definition] is in doubt". They may also be used to modify quotations. For example, if referring to someone's statement "I hate to do laundry", one could write: She "hate[s] to do laundry".

The bracketed expression "[sic]" is used after a quote or reprinted text to indicate the passage appears exactly as in the original source; a bracketed ellipsis [...] is often used to indicate deleted material; bracketed comments indicate when original text has been modified for clarity: "I'd like to thank [several unimportant people] and my parentals [sic] for their love, tolerance [...] and assistance [emphasis added]".[10]

Brackets are used in mathematics in a variety of notations, including standard notations for intervals, commutators, the floor function, the Lie bracket, the Iverson bracket, and matrices.

In translated works, brackets are used to signify the same word or phrase in the original language to avoid ambiguity.[11] For example: He is trained in the way of the open hand [karate].

When nested parentheses are needed, parentheses are used as a substitute for the inner pair of brackets within the outer pair.[12] When deeper levels of nesting are needed, convention is to alternate between parentheses and brackets at each level.

In linguistics, phonetic transcriptions are generally enclosed within brackets,[13] often using the International Phonetic Alphabet, while phonemic transcriptions typically use paired slashes.

Brackets can also be used in chemistry to represent the concentration of a chemical substance or to denote distributed charge in a complex ion.

Brackets (called move-left symbols or move right symbols) are added to the sides of text in proofreading to indicate changes in indentation:

| Move left | [To Fate I sue, of other means bereft, the only refuge for the wretched left. |

|---|---|

| Center | ]Paradise Lost[ |

| Move up |

Brackets are used to denote parts of the text that need to be checked when preparing drafts prior to finalizing a document. They often denote points that have not yet been agreed to in legal drafts and the year in which a report was made for certain case law decisions.

Curly brackets { }

Curly brackets – also called braces (US) or squiggly brackets (UK, informally ) are sometimes used in prose to indicate a series of equal choices: "Select your animal {goat, sheep, cow, horse} and follow me". They are used in specialized ways in poetry and music (to mark repeats or joined lines). The musical terms for this mark joining staves are accolade and "brace", and connect two or more lines of music that are played simultaneously.[14] In mathematics they delimit sets. In many programming languages, they enclose groups of statements. Such languages (C being one of the best-known examples) are therefore called curly bracket languages. Some people use a brace to signify movement in a particular direction.

Presumably due to the similarity of the words brace and bracket (although they do not share an etymology), many people mistakenly treat brace as a synonym for bracket. Therefore, when it is necessary to avoid any possibility of confusion, such as in computer programming, it may be best to use the term curly bracket rather than brace. However, general usage in North American English favours the latter form. Indian programmers often use the name "flower bracket".[15]

In classical mechanics, curly brackets are often also used to denote the Poisson bracket between two quantities. It is defined as follows:

Angle brackets or chevrons ⟨ ⟩

Chevrons ⟨ ⟩;[16] are often used to enclose highlighted material. Some dictionaries use chevrons to enclose short excerpts illustrating the usage of words.

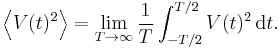

In physical sciences, chevrons are used to denote an average over time or over another continuous parameter. For example,

The inner product of two vectors is commonly written as  , but the notation (a, b) is also used.

, but the notation (a, b) is also used.

In mathematical physics, especially quantum mechanics, it is common to write the inner product between elements as  , as a short version of

, as a short version of  , or

, or  , where

, where  is an operator. This is known as Dirac notation or bra-ket notation.

is an operator. This is known as Dirac notation or bra-ket notation.

In set theory, chevrons or parentheses are used to denote ordered pairs and other tuples, whereas curly brackets are used for unordered sets.

In linguistics, chevrons indicate orthography, as in "The English word /kæt/ is spelled ⟨cat⟩." In epigraphy, they may be used for mechanical transliterations of a text into the Latin alphabet.

In textual criticism, and hence in many editions of poorly transmitted works, chevrons denote sections of the text which are illegible or otherwise lost; the editor will often insert his own reconstruction where possible within them.

Chevrons are infrequently used to denote dialogue that is thought instead of spoken, such as:

- ⟨ What a beautiful flower! ⟩

The mathematical or logical symbols for greater-than (>) and less-than (<) are inequality symbols, and are not punctuation marks when so used. Nevertheless, true chevrons are not available on a typical computer keyboard, but the less-than and greater-than symbols are, so they are often substituted. They are loosely referred to as angled brackets or chevrons in this case.

Single and double pairs of comparison operators (<<, >>) (meaning much smaller than and much greater than) are sometimes used instead of guillemets («, ») (used as quotation marks in many languages) when the proper glyphs are not available.

In comic books, chevrons are often used to mark dialogue that has been translated notionally from another language; in other words, if a character is speaking another language, instead of writing in the other language and providing a translation, one writes the translated text within chevrons. Of course, since no foreign language is actually written, this is only notionally translated.

Chevron-like symbols are part of standard Chinese, and Korean punctuation, where they generally enclose the titles of books: ︿ and ﹀ or ︽ and ︾ for traditional vertical printing, and 〈 and 〉 or 《 and 》 for horizontal printing. See also non-English usage of quotation marks.

Angle and half brackets 「」, ⌊ ⌋

In Chinese punctuation, angle brackets are used as quotation marks. Half brackets are used in English to mark added text, such as in translations: "Bill saw ⌊her⌋".

The corner brackets ⌈ and ⌉ have at least two uses in mathematical logic: first, as a generalization of quotation marks, and second, to denote the gödel number of the enclosed expression.

In editions of papyrological texts, half brackets enclose text which is lacking in the papyrus due to damage, but can be restored by virtue of another source, such as an ancient quotation of the text transmitted by the papyrus.[17] For example, Callimachus Iambus 1.2 reads: ἐκ τῶν ὅκου βοῦν κολλύ⌊βου π⌋ιπρήσκουσιν. A hole in the papyrus has obliterated βου π, but these letters are supplied by an ancient commentary on the poem.

Double brackets

In formal semantics, double brackets are used to indicate the semantic evaluation function. The CJK glyphs 〚 〛look identical except they have added width. They can be typeset in LaTeX with the package stmaryrd.

Computing

Encoding

- Opening and closing parentheses correspond to ASCII and Unicode characters U+0028 ( left parenthesis (HTML:

() and U+0029 ) right parenthesis (HTML:)), respectively. - For square brackets the code points are U+005B [ left square bracket (91 decimal) and U+005D ] right square bracket (93 decimal)

- For braces, Unicode names U+007B { left curly bracket (HTML:

{) and U+007D } right curly bracket (HTML:}). Braces first became part of a character set with the 8-bit code of the IBM 7030 Stretch.[18] - True chevrons are available in Unicode at multiple code points.

- Code points are U+27E8 ⟨ mathematical left angle bracket and U+27E9 ⟩ mathematical right angle bracket for mathematical use, or U+3008 〈 left angle bracket and U+3009 〉 right angle bracket for East Asian languages.

- A third set of chevrons are encoded at U+2329 〈 left pointing angle bracket (deprecated, see U+3008) and U+232A 〉 right pointing angle bracket (deprecated, see U+3009), but officially "discouraged for mathematical use"[19] because they are canonically equivalent to the CJK code points U+300x and thus likely to render as double-width symbols.

- The less-than and greater-than symbols are often used as replacements for chevrons. They are found in both Unicode and ASCII at code points U+003C < less-than sign (HTML:

<<) and U+003E > greater-than sign (HTML:>>).

These various bracket characters are frequently used in many computer languages as operators or for other syntax markup. The more common uses follow.

Uses of "(" and ")"

- are often used to define the syntactic structure of expressions, overriding operator precedence:

a*(b+c)has subexpressionsaandb+c, whereasa*b+chas subexpressionsa*bandc - passing parameters or arguments to functions, especially in C and similar languages, and invoking a function or function-like construct:

substring($val,10,1) - in Lisp, they open and close s-expressions and therefore function applications:

(cons a b) - in many regular expression syntaxes parentheses create a capturing group, allowing the matched portion inside to be retrieved by the user

- in Forth, they open and close comments in the code.

- in Fortran-family and COBOL languages, they are also used for array references

- in the Perl programming language through Perl 5, they are used to define lists, static array-like structures; this idiom is extended to their use as containers of subroutine (function) arguments

- in the Perl 6 programming language, they define captures, a structure that defers contextual interpretation. This usage extends to ordinary parentheses as well. They are also used to indicate arguments to function calls and to declare signatures of formal parameters or other variables.

- in Python they are used to disambiguate tuple literals (immutable ordered lists), which are usually formed by commas, in places where parentheses and commas would otherwise be a part of a function call.

- in Tcl they are used to enclose the name of an element of an associative array variable

- in joined brackets in a table form going vertically downwards, a ")" refers to repetition of a term for the number of items towards the left of this joined list of brackets.

Uses of "[" and "]"

- to refer to elements of an array or associative array, and sometimes to define the number of elements in an array, especially in C-like languages:

queue[3] - in many languages, may be used to define a literal anonymous array or list:

[5, 10, 15] - in most regular expression syntaxes brackets denote a character class: a set of possible characters to choose from

- in Forth, "[" causes the system to enter interpretation state and "]" causes the system to enter compilation state. For example, within a definition,

[ 2 3 + ] literalcauses the compiler to switch to the interpreter mode, calculate expression 2+3, leave the result on stack and resume compilation. As a result, a literal constant "5" will be compiled into the definition, instead of the whole expression. - in Tcl, they enclose a sub-script to be evaluated and the result substituted

- in some of Microsoft's .NET (CLI) languages, most notably C# and C++, they are used to denote metadata attributes.

- in x86 assembly implementations such as FASM, they are used to distinguish pointers from their data.

- in Smalltalk, brackets are used to delineate "blocks" or "block closures", grouping of code that can be executed immediately or later via messages send such as "value" sent to the block. Blocks are full first class objects in Smalltalk.

- in Objective-C, brackets are used to send a message to (i.e. call a method on) an object

- on Unix, "[" is a shorthand for the test command

- in JSON they are used to define an array. (an ordered sequence of comma-separated values)

- in programming manuals and metalanguages (e.g. in descriptions of operator or command syntax), optional elements are enclosed in square brackets

- delimiting IPv6 addresses in URLs, for example

http://[2001:db8:3c4d:15::abcd:ef12]:8080

Uses of "{" and "}"

- are used in some programming languages to define the beginning and ending of blocks of code or data. Languages which use this convention are said to belong to the curly bracket family of programming languages

- are used to represent certain type definitions or literal data values, such as a composite structure or associative array

- in mathematics they enclose elements of a set and denote a set

- in Curl they are used to delimit expressions and statements (similar to Lisp's use of parenthesis).

- in Pascal they define the beginning and ending of comments

- in most regular expression syntaxes, they are used as quantifiers, matching n repetitions of the previous group

- in Perl they are also used to refer to elements of an associative array

- in PHP they are used to determine structures.

- In Adobe Systems Actionscript they are used to denote structures of argument outcomes and functions

- in Tcl they enclose a string to be substituted without any internal substitutions being performed

- in Python and Ruby they are used for dictionaries (a mutable set of key: value pairs, separated by commas) and for sets.

- in TeX/LaTeX they can be used for grouping parts sharing the same local format, wrap parameters, or definitions, depending on the local catcode value

- in JSON they are used to define an object (an unordered collection of key:value pairs)

- in metalanguages (e.g. in descriptions of operator or command syntax), possible alternatives are enclosed in braces, if at least one is mandatory.

- These are also used in music at the start of a stave.

- In Objective-C they are used to mark the start and/or end of a process.

Uses of "<" and ">"

These symbols are used in pairs as if they are brackets,

- to set apart URLs and e-mail addresses in text, such as "I found it on Example.com <http://www.example.com/>" and "This photo is copyrighted by John Smith <john@smith.com>". This is also the computer-readable form for addresses in e-mail headers, specified by RFC 2822.

- in SGML (see HTML, XML), used to enclose code tags: ex.

<div> - in C++, C#, and Java they delimit generic arguments

- in Perl through Perl 5 they are used to read a line from an input source

- in Perl 6 they combine quoting and associative array lookup

- in ABAP they denote field symbols – placeholders or symbolic names for other fields, which can point to any data object.

- to indicate an action or status (e.g. <Waves> or <Offline>), particularly in online, real-time text-based discussions (instant messaging, bulletin boards, etc). (Here, asterisks can also be used to signify an action.)

When not used in pairs to delimit text (not acting as brackets):

- They are used as less-than and greater-than relational operators, possibly in combination with other marks. In some languages the pair together as

<>denotes an inequation ("not equal to"). - When doubled as

<<or>>they may represent bit shift operators, or in C++, also stream input/output operators. - They indicate the redirection of input/output in various command shells.[20]

- Right-angle brackets are used in nested Usenet quoting and various e-mail formats, and as such are standard quotation mark glyphs.

Layout styles

In normal writing (prose) an opening bracket is rarely left hanging at the end of a line of text nor is a closing bracket permitted to start one. However, in computer code this is often done intentionally to aid readability. For example, a bracketed list of items separated by semicolons may be written with the brackets on separate lines, and the items, followed by the semicolon, each on one line.

A common error in programming is mismatching braces; accordingly, many IDEs have braces matching to highlight matching pairs.

Mathematics

In addition to the use of parentheses to specify the order of operations, both parentheses and brackets are used to denote an interval, also referred to as a half-open range. The notation [a, c) is used to indicate an interval from a to c that is inclusive of a but exclusive of c. That is, [5, 12) would be the set of all real numbers between 5 and 12, including 5 but not 12. The numbers may come as close as they like to 12, including 11.999 and so forth (with any finite number of 9s), but 12.0 is not included. In Europe, the notation [5,12[ is also used for this. The endpoint adjoining the bracket is known as closed, while the endpoint adjoining the parenthesis is known as open. If both types of brackets are the same, the entire interval may be referred to as closed or open as appropriate. Whenever +∞ or −∞ is used as an endpoint, it is normally considered open and adjoined to a parenthesis. See Interval (mathematics) for a more complete treatment.

In quantum mechanics, chevrons are also used as part of Dirac's formalism, bra-ket notation, to note vectors from the dual spaces of the Bra (⟨A|) and the Ket (|B⟩). Mathematicians will also commonly write <a,b> for the inner product of two vectors. In statistical mechanics, Chevrons denote ensemble or time average. Chevrons are used in group theory to write group presentations, and to denote the subgroup generated by a collection of elements.

In group theory and ring theory, brackets denote the commutator. In group theory, the commutator [g,h] is commonly defined as g−1h−1gh. In ring theory, the commutator [a,b] is defined as ab − ba. Furthermore, in ring theory, braces denote the anticommutator where {a,b} is defined as ab + ba. The bracket is also used to denote the Lie derivative, or more generally the Lie bracket in any Lie algebra.

Various notations, like the vinculum have a similar effect to brackets in specifying order of operations, or otherwise grouping several characters together for a common purpose.

In the Z formal specification language, braces define a set and chevrons define a sequence.

Accounting

Traditionally in accounting, negative amounts are placed in parentheses.

Law

Brackets are used in some countries in the citation of law reports to identify parallel citations to non-official reporters. For example: Chronicle Pub. Co. v. Superior Court, (1998) 54 Cal.2d 548, [7 Cal.Rptr. 109]. In some other countries (such as England and Wales), square brackets are used to indicate that the year is part of the citation, as opposed to optional information. For example, National Coal Board v England [1954] AC 403, (1954) 98 Sol Jo 176 – the case report is in the 1954 volume of the Appeal Cases reports (year not optional) and in volume 98 of the Solicitor's Journal (year optional, since the volumes are numbered, and so given in round brackets).

When quoted material is in any way altered, the alterations are enclosed in brackets within the quotation. For example: Plaintiff asserts his cause is just, stating, "[m]y causes is [sic] just." While in the original quoted sentence the word "my" was capitalized, it has been modified in the quotation and the change signalled with brackets. Similarly, where the quotation contained a grammatical error, the quoting author signalled that the error was in the original with "[sic]" (Latin for "thus"). (California Style Manual, section 4:59 (4th ed.))

Sports

Tournament brackets, the diagrammatic representation of the series of games played during a tournament usually leading to a single winner, are so named for their resemblance to brackets or braces.

Typing

In roleplaying, and writing, brackets are used for out-of-speech sentences (otherwise known as OOC, out-of-character). Example:

(What's your name?)

To avoid ambiguity as to whether this is an in-character parenthetical statement or an out-of-character statement, in many circles double brackets are used, as they are unheard of in standard writing.

((How long have you played here?))

See also

References

- ^ "Bracket", American Heritage Dictionary" at Yahoo Education site

- ^ Free Online Dictionary of Computing

- ^ http://catb.org/jargon/html/B/broket.html

- ^ Truss, Lynne. Eats, Shoots & Leaves, 2003. p. 161. ISBN 1-59240-087-6.

- ^ The Free Online Dictionary

- ^ Robert Bringhurst, The Elements of Typographic Style, §5.3.2.

- ^ Slash (punctuation)#Gender-neutrality in Spanish and Portuguese

- ^ Fogarty, Mignon. "Parentheses, Brackets, and Braces". Quick and Dirty Tips. http://grammar.quickanddirtytips.com/parentheses-brackets-and-braces.aspx. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ The Chicago Manual of Style, 15th ed., The University of Chicago Press, 2003, §6.104

- ^ The Columbia Guide to Standard American English

- ^ The Chicago Manual of Style, 15th ed., The University of Chicago Press, 2003, §6.105

- ^ The Chicago Manual of Style, 15th ed., The University of Chicago Press, 2003, §6.102 and §6.106

- ^ The Chicago Manual of Style, 15th ed., The University of Chicago Press, 2003, §6.107

- ^ Decodeunicode.org > U+007B LEFT CURLY BRACKET Retrieved on May 3, 2009

- ^ K R Venugopal, Rajkumar Buyya, T Ravishankar. Mastering C++, 1999. p. 34. ISBN 0-07-463454-2.

- ^ Some fonts don't display these characters correctly. Please refer to the image on the right instead.

- ^ M.L. West (1973) Textual Criticism and Editorial Technique (Stuttgart) 81.

- ^ Bob, Bemer. "The Great Curly Brace Trace Chase". http://www.bobbemer.com/BRACES.HTM. Retrieved 2009-09-05

- ^ Unicode.org

- ^ Bryant, Randal E.; O'Hallaron, David. Computer Systems: A Programmer's Perspective, 2003. p. 794. ISBN 0-13-034074-X.

Bibliography

- Lennard, John (1991). But I Digress: The Exploitation of Parentheses in English Printed Verse. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-811247-5.

- Turnbull; et al. (1964). The Graphics of Communication. New York: Holt. States that what are depicted as brackets above are called braces and braces are called brackets. This was the terminology in US printing prior to computers.

![[(2%2B3)\times4]^2=400](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/413150a84f934de0a0e97a4f64575a9c.png)

![\{f,g\} = \sum_{i=1}^{N} \left[

\frac{\partial f}{\partial q_{i}} \frac{\partial g}{\partial p_{i}} -

\frac{\partial f}{\partial p_{i}} \frac{\partial g}{\partial q_{i}}

\right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/358755f883bc538bf1b85d0f02f96b0e.png)