Panspermia

Panspermia (Greek: πανσπερμία from πᾶς/πᾶν (pas/pan) "all" and σπέρμα (sperma) "seed") is the hypothesis that life exists throughout the Universe, distributed by meteoroids, asteroids and planetoids.[1]

Panspermia proposes that life that can survive the effects of space, such as extremophile bacteria, become trapped in debris that is ejected into space after collisions between planets that harbor life and Small Solar System Bodies (SSSB). Bacteria may travel dormant for an extended amount of time before colliding randomly with other planets or intermingling with protoplanetary disks. If met with ideal conditions on a new planet's surfaces, the bacteria become active and the process of evolution begins. Panspermia is not meant to address how life began, just the method that may cause its sustenance.[2]

The related but distinct idea of exogenesis (Greek: ἔξω (exo, "outside") and γένεσις (genesis, "origin")) is a more limited hypothesis that proposes life on Earth was transferred from elsewhere in the Universe but makes no prediction about how widespread it is. Because the term "exogenesis" is more well-known, it tends to be used in reference to what should strictly speaking be called panspermia.

Contents |

Hypothesis

The first known mention of the term was in the writings of the 5th century BC Greek philosopher Anaxagoras.[3] In the nineteenth century it was again revived in modern form by several scientists, including Jöns Jacob Berzelius (1834),[4] Kelvin (1871),[5] Hermann von Helmholtz (1879) and, somewhat later, by Svante Arrhenius (1903).[6] There is as yet no evidence to support or contradict panspermia, although the majority view holds that panspermia – especially in its interstellar form – is unlikely given the challenges of survival and transport in space. Sir Fred Hoyle (1915–2001) and Chandra Wickramasinghe (born 1939) were important proponents of the hypothesis who further contended that lifeforms continue to enter the Earth's atmosphere, and may be responsible for epidemic outbreaks, new diseases, and the genetic novelty necessary for macroevolution.[7]

Panspermia does not necessarily suggest that life originated only once and subsequently spread through the entire Universe, but instead that once started, it may be able to spread to other environments suitable for replication.

Proposed mechanisms

The mechanisms proposed for interstellar panspermia are hypothetical and currently unproven. Panspermia can be said to be either interstellar (between star systems) or interplanetary (between planets in the same star system); its transport mechanisms may include radiation pressure and lithopanspermia (microorganisms in rocks).[8][9] Deliberate directed panspermia from space to seed Earth[10] or sent from Earth to seed other solar systems[11][12][13] have also been proposed. One new twist to the hypothesis by engineer Thomas Dehel (2006), proposes that plasmoid magnetic fields ejected from the magnetosphere may move the few spores lifted from the Earth's atmosphere with sufficient speed to cross interstellar space to other systems before the spores can be destroyed.[14][15]

Interplanetary transfer of material is well documented, as evidenced by meteorites of Martian origin found on Earth.

Space probes may also be a viable transport mechanism for interplanetary cross-pollination in our solar system or even beyond. However, space agencies have implemented sterilization procedures to avoid planetary contamination.[16][17]

Stardust Space Probe - The link between Comets and Panspermia was investigated further with a NASA Launch performed by NASA beginning in 2004, entitled "The Stardust Mission". Ion Propulsion spacecraft was loaded with machinery to bring back lab samples from the tail of a comet. This published document from NASA entitled "NASA Researchers Make First Discovery of Life's Building Blocks in Comet".[18] This article refers to the Glycine and other building blocks that have been found in comets. Comets travel through space with these frozen potentially reproductive materials, and the tail of the comets appear when gases melt in the presence of our sun.

Research

Until a large portion of the galaxy is surveyed for signs of life or contact is made with hypothetical extraterrestrial civilizations, the panspermia hypothesis in its fullest meaning will remain difficult to test.

Early life on Earth

The Precambrian fossil record indicates that life appeared soon after the Earth was formed. This would imply that life appeared within several hundred million years when conditions became favourable. Generally accepted scientific estimates of the age of the Earth place its formation (along with the rest of the Solar system) at about 4.55 billion years old. The oldest known sedimentary rocks are somewhat altered Hadean formations from the southern tip of Akilia island, West Greenland. These rocks have been dated as no younger than 3.85 billion years.[19][20][21][22]

The oldest known fossilized stromatolites or bacterial aggregates, are dated at 3.5 billion years old. The bacteria that form stromatolites, cyanobacteria, are photosynthetic. Most models of the origin of life have the earliest organisms obtaining energy from reduced chemicals, with the more complex mechanisms of photosynthesis evolving later. During the Late Heavy Bombardment of the Earth's Moon about 3.9 billion years (as evidenced by Apollo lunar samples) impact intensities may have been up to 100x those immediately before.[23] From analysis of lunar melts and observations of similar cratering on Mars' highlands, Kring and Cohen suggest that the Late Heavy Bombardment was caused by asteroid impacts that affected the entire inner solar system.[24] This is likely to have effectively sterilised Earth's entire planetary surface, including submarine hydrothermal systems that would be otherwise protected.[23]

Extremophiles

Astrobiologists are particularly interested in studying extremophiles as many organisms of this type are capable of surviving in environments similar to those known to exist on other planets. Some organisms have been shown to be more resistant to extreme conditions than previously recognized, and may be able to survive for very long periods of time, probably even in deep space and, hypothetically, could travel in a dormant state between environments suitable for ongoing life.

Some bacteria and animals have been found to thrive in oceanic hydrothermal vents above 100 °C; a study revealed that a fraction of bacteria survive heating pulses up to 250°C in vacuum, while similar heating at normal atmospheric pressure leads to the total sterilization of samples.[25] Other bacteria can thrive in strongly caustic environments, others at extreme pressures 11 km under the ocean,[26] while others survive in extremely dry, desiccating conditions, frigid cold, vacuum or acid environments. Survival in space is not limited to bacteria, lichens or archea:[27][28] the animal Tardigrade has been proven to survive the vacuum of space.[29]

Recent experiments suggest that if bacteria were somehow sheltered from the radiation of space, perhaps inside a thick meteoroid or an icy comet, they could survive dormant for millions of years. Deinococcus radiodurans is a radioresistant bacterium that can survive high radiation levels. Duplicating the harsh conditions of cold interstellar space in their laboratory, NASA scientists have created primitive vesicles that mimic some aspects of the membraneous structures found in all living things. These chemical compounds may have played a part in the origin of life.[30]

Spores

Spores are another potential vector for transporting life through inhospitable and inimical environments, such as the depths of interstellar space.[31][32] Spores are produced as part of the normal life cycle of many plants, algae, fungi and some protozoans, and some bacteria produce endospores or cysts during times of stress. These structures may be highly resilient to ultraviolet and gamma radiation, desiccation, lysozyme, temperature, starvation and chemical disinfectants, while metabolically inactive. Spores germinate when favourable conditions are restored after exposure to conditions fatal to the parent organism. According to astrophysicist Dr. Steinn Sigurdsson, "There are viable bacterial spores that have been found that are 40 million years old on Earth - and we know they're very hardened to radiation."[13]

Potential habitats for life

The presence of past liquid water on Mars, suggested by river-like formations on the red planet, was confirmed by the Mars Exploration Rover missions. In December 2006, Michael C. Malin of Malin Space Science Systems published a paper in the journal Science which argued that his camera (the Mars Observer Camera) had found evidence suggesting water was occasionally flowing on the surface of Mars within the last five years.

Water oceans might exist on Europa, Enceladus, Triton and perhaps other moons in the Solar system. Even moons that are now frozen ice balls might earlier have been melted internally by heat from radioactive rocky cores. Bodies like this may be common throughout the universe. Living bacteria found in core samples retrieved from 3,700 metres (12,100 ft) deep at Lake Vostok in Antarctica, have provided data for extrapolations to the likelihood of microorganisms surviving frozen in extraterrestrial habitats or during interplanetary transport.[33] Also, bacteria have been discovered living within warm rock deep in the Earth's crust.[34]

Extraterrestrial life

Earth is the only place known by human beings to harbor life in the observed universe. Today's estimates of values for the Drake Equation suggest the probability of intelligent life in a single galaxy like our own Milky Way may be much smaller than once was thought, while the sheer number of galaxies make it seem probable that life has arisen somewhere else in the Universe.[35] According to current theories of physics, space travel over such vast distances would take an incredibly long time to the outside observer, with vast amounts of energy required. Nevertheless, small groups of researchers like the Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence (SETI) continue to monitor the skies for transmissions from within our own galaxy at least.

Astrobiological proponents like the Rare Earth hypothesists recognise that the conditions required for the evolution of intelligent life might be exceedingly rare in the Universe, while simultaneously noting that simple single-celled microorganisms may well be abundant.[36]

Spaceborne organic molecules

A 2008 analysis of 12C/13C isotopic ratios of organic compounds found in the Murchison meteorite indicates a non-terrestrial origin for these molecules rather than terrestrial contamination. Biologically relevant molecules identified so far include uracil, an RNA nucleobase, and xanthine.[37][38] These results demonstrate that many organic compounds which are components of life on Earth were already present in the early solar system and may have played a key role in life's origin.[39]

In August 2009, NASA scientists identified one of the fundamental chemical building-blocks of life (the amino acid glycine) in a comet for the first time.[40]

On August 8, 2011, a report, based on NASA studies with meteorites found on Earth, was published suggesting building blocks of DNA (adenine, guanine and related organic molecules) may have been formed extraterrestrially in outer space.[41][42][43] In October 2011, scientists reported that cosmic dust contains complex organic matter ("amorphous organic solids with a mixed aromatic-aliphatic structure") that could be created naturally, and rapidly, by stars.[44][45][46] One of the scientists suggested that these complex organic compounds may have been related to the development of life on earth and said that, "If this is the case, life on Earth may have had an easier time getting started as these organics can serve as basic ingredients for life." [44]

Still under investigation/undetermined

- Of the four Viking biological experiments performed by the Mars lander Viking in 1976, only the LR (Labeled Release) experiment gave results that were initially indicative of life (metabolism). However, the similar results from heated controls, how the release of indicative gas tapered off, and the lack of organic molecules in soil samples all suggest that the results were the result of a non-living chemical reaction rather than biological metabolism. Later experiments showed that existing oxidizers in the Martian soil could reproduce the results of the positive LR Viking experiment. Despite this, the Viking's LR experiment designer remains convinced that it is diagnostic for life on Mars.[47]

- A meteorite originating from Mars known as ALH84001 was shown in 1996 to contain microscopic structures resembling small terrestrial nanobacteria. When the discovery was announced, many immediately conjectured that these were fossils and were the first evidence of extraterrestrial life — making headlines around the world. Public interest soon started to dwindle as most experts started to agree that these structures were not indicative of life, but could instead be formed abiotically from organic molecules. However, in November 2009, a team of scientists at Johnson Space Center, including David McKay, reasserted that there was "strong evidence that life may have existed on ancient Mars", after having reexamined the meteorite and finding magnetite crystals.[48][49]

- On May 11, 2001, two researchers from the University of Naples claimed to have found live extraterrestrial bacteria inside a meteorite. Geologist Bruno D'Argenio and molecular biologist Giuseppe Geraci claim the bacteria were wedged inside the crystal structure of minerals, but were resurrected when a sample of the rock was placed in a culture medium. They believe that the bacteria were not terrestrial because they survived when the sample was sterilized at very high temperature and washed with alcohol. They also claim that the bacteria's DNA is unlike any on Earth.[50][51] They presented a report on May 11, 2001, concluding that this is the first evidence of extraterrestrial life, documented in its genetic and morphological properties. Some of the bacteria they discovered were found inside meteorites that have been estimated to be over 4.5 billion years old, and were determined to be related to modern day Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus pumilis bacteria on Earth but appears to be a different strain.[52]

- An Indian and British team of researchers led by Chandra Wickramasinghe reported on 2001 that air samples over Hyderabad, India, gathered from the stratosphere by the Indian Space Research Organization, contained clumps of living cells. Wickramasinghe calls this "unambiguous evidence for the presence of clumps of living cells in air samples from as high as 41 km, above which no air from lower down would normally be transported".[53][54] Two bacterial and one fungal species were later independently isolated from these filters which were identified as Bacillus simplex, Staphylococcus pasteuri and Engyodontium album respectively.[55] The experimental procedure suggested that these were not the result of laboratory contamination, although similar isolation experiments at separate laboratories were unsuccessful.

- A reaction report at NASA Ames indicated skepticism towards the premise that Earth life cannot travel to and reside at such altitudes.[56] Max Bernstein, a space scientist associated with SETI and Ames, argues the results should be interpreted with caution, noting that "it would strain one's credulity less to believe that terrestrial organisms had somehow been transported upwards than to assume that extraterrestrial organisms are falling inward".[53] Pushkar Ganesh Vaidya from the Indian Astrobiology Research Centre reported in his 2009 paper that "the three microorganisms captured during the balloon experiment do not exhibit any distinct adaptations expected to be seen in microorganisms occupying a cometary niche".[57][58]

- In 2005 an improved experiment was conducted by ISRO. On April 10, 2005 air samples were collected from six places at different altitudes from the earth ranging from 20 km to more than 40 km. Adequate precautions were taken to rule out any contamination from any microorganisms already present in the collection tubes. The samples were tested at two labs in India. The labs found 12 bacterial and 6 fungal colonies in these samples. The fungal colonies were Penicillium decumbens, Cladosporium cladosporioides, Alternaria sp. and Tilletiopsis albescens. Out of the 12 bacterial samples, three were identified as new species and named Janibacter hoyeli.sp.nov (after Fred Hoyle), Bacillus isronensis.sp.nov (named after ISRO) and Bacillus aryabhati (named after the ancient Indian mathematician, Aryabhata). These three new species showed that they were more resistant to UV radiation than similar bacteria found on Earth. For any organism living so far up the Earth's atmosphere or having come from outside Earth, the UV radiation resistance would be extremely critical for survival.[59][60]

Disputed

A NASA research group found a small number of Streptococcus mitis bacteria living inside the camera of the Surveyor 3 spacecraft when it was brought back to Earth by Apollo 12. They believed that the bacteria survived since the time of the craft's launch to the Moon.[61] However, these reports are disputed by Leonard D. Jaffe, who was Surveyor program scientist and custodian of the Surveyor 3 parts brought back from the Moon, stated in a letter to the Planetary Society that an unnamed member of his staff reported that a "breach of sterile procedure" took place at just the right time to produce a false positive result.[62] NASA was funding an archival study in 2007 that was trying to locate the film of the camera-body microbial sampling to confirm the report of a breach in sterile technique. NASA currently stands by its original assessment: see Reports of Streptococcus mitis on the moon.

Hoaxes

A separate fragment of the Orgueil meteorite (kept in a sealed glass jar since its discovery) was found in 1965 to have a seed capsule embedded in it, whilst the original glassy layer on the outside remained undisturbed. Despite great initial excitement, the seed was found to be that of a European Juncaceae or Rush plant that had been glued into the fragment and camouflaged using coal dust. The outer "fusion layer" was in fact glue. Whilst the perpetrator of this hoax is unknown, it is thought he sought to influence the 19th century debate on spontaneous generation — rather than panspermia — by demonstrating the transformation of inorganic to biological matter.[63]

Objections to panspermia and exogenesis

- Life as we know it requires the elements hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, iron, phosphorus and sulfur (H, C, N, O, Fe, P, and S respectively) to exist at sufficient densities and temperatures for the chemical reactions between them to occur. These conditions are not widespread in the Universe, so this limits the distribution of life as an ongoing process. First, the elements C, N and O are only created after at least one cycle of star birth/death: this is a limit to the earliest time life could have arisen. Second, densities of elements sufficient for the formation of more complex molecules necessary to life (such as amino acids) only occur in molecular dust clouds (109–1012 particles/m3), and (following their collapse) in solar systems. Third, temperatures must be lower than those in stars (elements are stripped of electrons: a plasma state) but higher than in the interstellar medium (reaction rates are too low). This restricts ongoing life to planetary environments where heavy elements are present at high densities, so long as temperatures are sufficient for plausible reaction rates. Note this does not restrict dormant forms of life to these environments, so this argument only contradicts the widest interpretation of panspermia — that life is ongoing and is spread across many different environments throughout the Universe — and presupposes that any life needs those elements, which the proponents of alternative biochemistries do not consider certain. Recent findings have boosted or even confirmed these alternative biochemistry theories with the discovery that arsenic can act as a building block of life.[64] However, the principal researcher for that finding is no longer sure that it is correct.[65]

- Space is a damaging environment for life, as it would be exposed to radiation, cosmic rays and stellar winds. Studies of bacteria frozen in Antarctic glaciers have shown that DNA has a half-life of 1.1 million years under such conditions, suggesting that while life may have potentially moved around within the Solar System it is unlikely that it could have arrived from an interstellar source.[66] Environments may exist within meteors or comets that are somewhat shielded from these hazards. However, the extreme resistance of Deinococcus radiodurans to radiation, cold, dehydration and vacuum shows that at least one known organism is capable of surviving the hazards of space without need for special protection.

- Bacteria would not survive the immense heat and forces of an impact on Earth — no conclusions (whether positive or negative) have yet been reached on this point. However, most of the heat generated when a meteor enters the Earth's atmosphere is carried away by ablation and the interiors of freshly landed meteorites are rarely heated much and are often cold. For example, a sample of hundreds of nematode worms on the space shuttle Columbia survived its crash landing from 63 km inside a 4 kg locker, and samples of already dead moss were not damaged. Though this is not a very good example, being protected by the man-made locker and possibly pieces of the shuttle, it lends some support to the idea that life could survive a trip through the atmosphere.[67] The existence of Martian meteorites and Lunar meteorites on Earth suggests material transfer from other celestial bodies to Earth happens regularly.

- Supporters of exogenesis also argue that on a larger scale, for life to emerge in one place in the Universe and subsequently spread to other planets would be simpler than similar life emerging separately on different planets. Thus, finding any evidence of extraterrestrial life similar to ours would lend credibility to exogenesis. However, this again assumes that the emergence of life in the entire Universe is rare enough as to limit it to one or few events or origination sites. Exogenesis still requires life to have originated from somewhere, most probably some form of geogenesis. Given the immense expanse of the entire Universe, it has been argued that there is a higher probability that there exists (or has existed) another Earth-like planet that has yielded life (geogenesis) than not. This explanation is more preferred under Occam's Razor than exogenesis since it theorizes that the creation of life is a matter of probability and can occur when the correct conditions are met rather than in exogenesis that assumes it is a singular event or that Earth did not meet those conditions on its own. In other words, exogenesis theorizes only one or few origins of life in the Universe, whereas geogenesis theorizes that it is a matter of probability depending on the conditions of the celestial body. Consider that even the most rare events on Earth can happen multiple times and independent of one another. However, since to date no extraterrestrial life has been confirmed, both theories still suffer from lack of information and too many unidentified variables.

- Even if life were to survive the hardships of space, or further, was being created in space, these would be very enduring life forms, as the theory itself proposes, and they would have already visibly populated and altered Venus and Mars as well as other moons in the solar system. The absence of life in Venus, with a somewhat similar composition to Earth's primitive conditions [68][69] or the absence of life on Mars, given the proposed "resilience" of life in space, also negates this as a viable theory, at least from what can be observed in our own Solar System: Life would be hyper abundant all around our Solar System if this theory were true, and we observe the opposite, except on Earth.

Accidental panspermia

Thomas Gold a professor of astronomy suggested a "garbage theory" for the origin of life, the theory says that life on Earth might have spread from a pile of waste products accidentally dumped on Earth long ago by extraterrestrials.[70]

Directed panspermia

A second prominent proponent of panspermia was the late Nobel prize winner Professor Francis Crick, who along with Leslie Orgel proposed the hypothesis of 'directed panspermia'.[10] This proposes that the seeds of life may have been purposely spread by an advanced extraterrestrial civilization. Later, after biologists had proposed that an "RNA world" might be involved in the origin of life, Crick noted that he had been overly pessimistic about the chances of life originating on Earth.[71]

The application of directed panspermia has been proposed as a way to spread life from Earth to other solar systems.[12] For example, microbial payloads launched by solar sails at speeds up to 0.0001 c (30,000 m/s) would reach targets at 10 to 100 light-years in 0.1 million to 1 million years. Fleets of microbial capsules can be aimed at clusters of new stars in star-forming clouds where they may land on planets, or captured by asteroids and comets and later delivered to planets. Payloads may contain extremophiles for diverse environments and cyanobacteria similar to early microorganisms. Hardy multicellular organisms (rotifer cysts) may be included to induce higher evolution.[72]

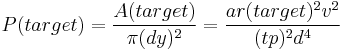

The probability of hitting the target zone can be calculated from  where A(target) is the cross-section of the target area, dy is the positional uncertainty at arrival; a - constant (depending on units), r(target) is the radius of the target area; v the velocity of the probe; (tp) the targeting precision (arcsec/yr); and d the distance to the target (all units in SIU). Guided by high-resolution astrometry of 1×10−5 arcsec/yr, almost nearby target stars (Alpha PsA, Beta Pictoris) can be seeded by milligrams of launched microbes; while seeding the Rho Ophiochus star-forming cloud requires hundreds of kilograms of dispersed capsules.[12]

where A(target) is the cross-section of the target area, dy is the positional uncertainty at arrival; a - constant (depending on units), r(target) is the radius of the target area; v the velocity of the probe; (tp) the targeting precision (arcsec/yr); and d the distance to the target (all units in SIU). Guided by high-resolution astrometry of 1×10−5 arcsec/yr, almost nearby target stars (Alpha PsA, Beta Pictoris) can be seeded by milligrams of launched microbes; while seeding the Rho Ophiochus star-forming cloud requires hundreds of kilograms of dispersed capsules.[12]

Theoretically, terrestrial spacecraft travelling to other celestial bodies such as the Moon, could carry with them microorganisms or other organic materials ubiquitous on Earth, thus raising the possibility that we can seed life on other planetary bodies. This is a concern among space researchers who try to prevent Earth contamination from distorting data, especially in regards to finding possible extraterrestrial life. Even the best sterilization techniques cannot guarantee that potentially invasive biologic or organic materials will not be unintentionally carried along. The harsh environments encountered throughout the rest of the solar system so far do not seem to support complex terrestrial life. However, matter exchange in form of meteor impacts has existed and will exist in the solar system even without human intervention.

Foton-M3 spacecraft

In September 2007, after enduring a 12-day orbital mission and a fiery reentry, the European unmanned spacecraft Foton-M3 was retrieved from a field in Kazakhstan.[73] The 5,500-pound capsule, seven-feet in diameter, carried a payload of 43 European experiments in a range of scientific disciplines – including fluid physics, biology, crystal growth, radiation exposure and astrobiology.[74] The capsule contained, among other things, lichen that were exposed to the radiation of space. Scientists also strapped basalt and granite disks riddled with cyanobacteria to the capsule's heat shield to see if the microorganisms could survive the brutal conditions of reentry. Some bacteria, lichens, spores, and even one animal (Tardigrades) were found to have survived the outer space environment and cosmic radiation.[27][28][29]

The Living Interplanetary Flight Experiment

The Living Interplanetary Flight Experiment, which is being developed by the Planetary Society, will consist of sending selected microorganisms on a three-year interplanetary round-trip in a small capsule aboard the Russian Fobos-Grunt spacecraft in 2011. The goal is to test whether organisms can survive a few years in deep space. The experiment will test one aspect of transpermia, the hypothesis that life could survive space travel, if protected inside rocks blasted by impact off one planet to land on another.[75][76]

See also

References

- ^ Rampelotto, P. H. (2010). Panspermia: A promising field of research. In: Astrobiology Science Conference. Abs 5224.

- ^ A variation of the panspermia hypothesis is necropanspermia which is described by astronomer Paul Wesson as follows: "The vast majority of organisms reach a new home in the Milky Way in a technically dead state ... Resurrection may, however, be possible." Grossman, Lisa (2010-11-10). "All Life on Earth Could Have Come From Alien Zombies". Wired. http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2010/11/necropanspermia/. Retrieved 2010-11-10.

- ^ Margaret O'Leary (2008) Anaxagoras and the Origin of Panspermia Theory, iUniverse publishing Group, # ISBN 978-0-595-49596-2

- ^ Berzelius (1799-1848), J. J.. Analysis of the Alais meteorite and implications about life in other worlds

- ^ Thomson (Lord Kelvin), W. (1871). "Inaugural Address to the British Association Edinburgh. "We must regard it as probably to the highest degree that there are countless seed-bearing meteoritic stones moving through space."". Nature 4 (92): 261–278 [262]. doi:10.1038/004261a0

- ^ Arrhenius, S., Worlds in the Making: The Evolution of the Universe. New York, Harper & Row, 1908.

- ^ Fred Hoyle, Chandra Wickramasinghe and John Watson, Viruses from Space and Related Matters, University College Cardiff Press, 1986.

- ^ Weber, P; Greenberg, J. M. (1985). "Can spores survive in interstellar space?". Nature 316 (6027): 403–407. Bibcode 1985Natur.316..403W. doi:10.1038/316403a0

- ^ Melosh, H. J. (1988). "The rocky road to panspermia". Nature 332 (6166): 687–688. Bibcode 1988Natur.332..687M. doi:10.1038/332687a0. PMID 11536601

- ^ a b Crick, F. H.; Orgel, L. E. (1973). "Directed Panspermia". Icarus 19: 341–348. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(73)90110-3+[http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1979JBIS...32..419M]

- ^ Mautner, M; Matloff, G. (1979). "Directed panspermia: A technical evaluation of seeding nearby solar systems". J. British Interplanetary Soc. 32: 419

- ^ a b c Mautner, M. N. (1997). "Directed panspermia. 3. Strategies and motivation for seeding star-forming clouds". J. British Interplanetary Soc. 50: 93

- ^ a b BBC Staff (23 August 2011). "Impacts 'more likely' to have spread life from Earth". BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-14637109. Retrieved 2011-08-24.

- ^ "Electromagnetic space travel for bugs? - space - 21 July 2006 - New Scientist Space". Space.newscientist.com. http://space.newscientist.com/article/dn9601-electromagnetic-space-travel-for-bugs.html. Retrieved 2009-08-20.

- ^ Dehel, T. (2006-07-23). "Uplift and Outflow of Bacterial Spores via Electric Field". 36th COSPAR Scientific Assembly. Held 16 - 23 July 2006 (Adsabs.harvard.edu) 36: 1. Bibcode 2006cosp...36....1D.

- ^ Studies Focus On Spacecraft Sterilization

- ^ European Space Agency: Dry heat sterilisation process to high temperatures

- ^ NASA Researchers Make First Discovery of Life's Building Blocks in Comet

- ^ Schidlowski, M. (May 1988). "A 3,800-Million-Year Isotopic Record Of Life From Carbon In Sedimentary-Rocks". Nature 333 (6171): 313–318. Bibcode 1988Natur.333..313S. doi:10.1038/333313a0.

- ^ Gilmour I, Wright I, Wright J 'Origins of Earth and Life', The Open University, 1997, ISBN 0-7492-8182-0

- ^ Nisbet E (June 2000). "The realms of Archaean life". Nature 405 (6787): 625–6. doi:10.1038/35015187. PMID 10864305.

- ^ Lepland A, van Zuilen M, Arrhenius G, Whitehouse M and Fedo C, Questioning the evidence for Earth's earliest life — Akilia revisited, Geology; January 2005; v. 33; no. 1; p. 77-79; DOI: 10.1130/G20890.1

- ^ a b Cohen BA, Swindle TD, Kring DA (December 2000). "Support for the lunar cataclysm hypothesis from lunar meteorite impact melt ages". Science 290 (5497): 1754–6. Bibcode 2000Sci...290.1754C. doi:10.1126/science.290.5497.1754. PMID 11099411. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=11099411.

- ^ Kring DA, Cohen BA (2002) Cataclysmic bombardment throughout the inner solar system 3.9-4.0 Ga. J GEOPHYS RES-PLANET 107 (E2): art. no. 5009

- ^ Pavlov AK, Shelegedin VN, Kogan VT, Pavlov AA, Vdovina MA, Tret'iakov AV (2007). "[Can microorganisms survive upon high-temperature heating during the interplanetary transfer by meteorites?]" (in Russian). Biofizika 52 (6): 1136–40. PMID 18225667.

- ^ "Science/Nature | Life flourishes at crushing depth". BBC News. 2005-02-04. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/4235979.stm. Retrieved 2009-08-20.

- ^ a b Experiment lithopanspermia: test of interplanetary transfer and re-entry process of epi- and endolithic microbial communities in the FOTON-M3 Mission

- ^ a b "LIFE IN SPACE FOR LIFE ON EARTH - Biosatelite Foton M3". June 26, 2008. http://www.congrex.nl/08a09/Sessions/26-06%20Session%202a.htm. Retrieved 2009-10-13.

- ^ a b "Tardigrades survive exposure to space in low Earth orbit". Current Biology 18 (17): R729–R731. 9 September 2008. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.06.048. PMID 18786368. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6VRT-4TD6241-8&_user=10&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&_docanchor=&view=c&_searchStrId=1046838032&_rerunOrigin=scholar.google&_acct=C000050221&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=10&md5=761b97d947706378039a09e4ae887166. Retrieved 2009-10-13.

- ^ "Scientists Find Clues That Life Began in Deep Space :: Astrobiology Magazine - earth science - evolution distribution Origin of life universe - life beyond". Astrobio.net. http://astrobio.net/news/modules.php?op=modload&name=News&file=article&sid=122&mode=thread&order=0&thold=0. Retrieved 2009-08-20.

- ^ The BIOPAN experiment MARSTOX II of the FOTON M-3 mission July 2008.

- ^ Surviving the Final Frontier. 25 November 2002.

- ^ "Detection, recovery, isolation, and characterization of bacteria in glacial ice and Lake Vostok accretion ice". Ohio State University. 2002. http://etd.ohiolink.edu/view.cgi?acc_num=osu1015965965. Retrieved 2011-02-04.

- ^ Nanjundiah, V. (2000). "The smallest form of life yet?". Journal of Biosciences 25 (1): 9–10. doi:10.1007/BF02985175. PMID 10824192. http://eprints.iisc.ernet.in/archive/00001799/01/25smallest25(1)-9to10mar2000.pdf

- ^ See shrinking estimates of parameter values (since its inception in 1961) as discussed throughout the Drake equation article.

- ^ Webb, Stephen, 2002. If the universe is teeming with aliens, where is everybody? Fifty solutions to the Fermi paradox and the problem of extraterrestrial life. Copernicus Books (Springer Verlag)

- ^ Martins, Zita; Botta, Oliver; Fogel, Marilyn L.; Sephton, Mark A.; Glavin, Daniel P.; Watson, Jonathan S.; Dworkin, Jason P.; Schwartz, Alan W. et al. (15 June 2008). "Extraterrestrial nucleobases in the Murchison meteorite". Earth and Planetary Science Letters 270 (1–2): 130–136. Bibcode 2008E&PSL.270..130M. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2008.03.026.

- ^ AFP Staff (20 August 2009). "We may all be space aliens: study". AFP. http://afp.google.com/article/ALeqM5j_QHxWNRNdiW35Qr00L8CkwcXyvw. Retrieved 2011-08-14.

- ^ Martins, Zita; Oliver Botta, Marilyn L. Fogel Mark A. Sephton, Daniel P. Glavin, Jonathan S. Watson, Jason P. Dworkin, Alan W. Schwartz, Pascale Ehrenfreund. (Available online 20 March 2008). "Extraterrestrial nucleobases in the Murchison meteorite" (PDF). Earth and Planetary Science Letters. http://astrobiology.gsfc.nasa.gov/analytical/PDF/Martinsetal2008.pdf. Retrieved 2008-10-07.

- ^ "'Life chemical' detected in comet". NASA (BBC News). 18 August 2009. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/8208307.stm. Retrieved 2010-03-06.

- ^ Callahan; Smith, K.E.; Cleaves, H.J.; Ruzica, J.; Stern, J.C.; Glavin, D.P.; House, C.H.; Dworkin, J.P. (11 August 2011). "Carbonaceous meteorites contain a wide range of extraterrestrial nucleobases". PNAS. doi:10.1073/pnas.1106493108. http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2011/08/10/1106493108. Retrieved 2011-08-15.

- ^ Steigerwald, John (8 August 2011). "NASA Researchers: DNA Building Blocks Can Be Made in Space". NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/topics/solarsystem/features/dna-meteorites.html. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

- ^ ScienceDaily Staff (9 August 2011). "DNA Building Blocks Can Be Made in Space, NASA Evidence Suggests". ScienceDaily. http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/08/110808220659.htm. Retrieved 2011-08-09.

- ^ a b Chow, Denise (26 October 2011). "Discovery: Cosmic Dust Contains Organic Matter from Stars". Space.com. http://www.space.com/13401-cosmic-star-dust-complex-organic-compounds.html. Retrieved 2011-10-26.

- ^ ScienceDaily Staff (26 October 2011). "Astronomers Discover Complex Organic Matter Exists Throughout the Universe". ScienceDaily. http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/10/111026143721.htm. Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ^ Kwok, Sun; Zhang, Yong (26 October 2011). "Mixed aromatic–aliphatic organic nanoparticles as carriers of unidentified infrared emission features". Nature 479 (7371): 80. doi:10.1038/nature10542.

- ^ The Carnegie Institution Geophysical Laboratory Seminar, "Analysis of evidence of Mars life" held 14 May 2007; Summary of the lecture given by Gilbert V. Levin, Ph.D. http://arxiv.org/abs/0705.3176, published by Electroneurobiología vol. 15 (2), pp. 39–47, 2007

- ^ "New Study Adds to Finding of Ancient Life Signs in Mars Meteorite". NASA. 2009-11-30. http://www.nasa.gov/centers/johnson/news/releases/2009/J09-030.html. Retrieved 2009-12-01.

- ^ Thomas-Keprta, K., S. Clemett, D. McKay, E. Gibson and S. Wentworth 2009. Origin of Magnetite Nanocrystals in Martian Meteorite ALH84001 journal Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta: 73. 6631-6677.

- ^ "Alien visitors - 11 May 2001 - New Scientist Space". Space.newscientist.com. http://space.newscientist.com/article/dn725. Retrieved 2009-08-20.

- ^ D’Argenio, Bruno; Giuseppe Geraci and Rosanna del Gaudio (March, 2001). "Microbes in rocks and meteorites: a new form of life unaffected by time, temperature, pressure". Rendiconti Lincei 12 (1): 51–68. doi:10.1007/BF02904521. http://www.springerlink.com/content/q3215249n6853188/. Retrieved 2009-10-13.

- ^ http://www.lincei.it/pubblicazioni/rendicontiFMN/rol/pdf/S2001-01-04.pdf

- ^ a b "Scientists Say They Have Found Extraterrestrial Life in the Stratosphere But Peers Are Skeptical: Scientific American". Sciam.com. 2001-07-31. http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?articleID=000D499B-4662-1C60-B882809EC588ED9F. Retrieved 2009-08-20.

- ^ Narlikar JV, Lloyd D, Wickramasinghe NC, et al. (2003). "Balloon experiment to detect micro-organisms in the outer space". Astrophys Space Science 285 (2): 555–62. Bibcode 2003Ap&SS.285..555N. doi:10.1023/A:1025442021619. http://www.springerlink.com/content/jp0232r03v023701/?p=3a22f0bdfe244d668927fa1d782a2b8e&pi=27.

- ^ M. Wainwright, N.C. Wickramasinghe, J.V. Narlikar, P. Rajaratnam. "Microorganisms cultured from stratospheric air samples obtained at 41km". http://meghnad.iucaa.ernet.in/~jvn/FEMS.html. Retrieved 2007-05-11.Wainwright M (2003). "A microbiologist looks at panspermia". Astrophys Space Science 285 (2): 563–70. Bibcode 2003Ap&SS.285..563W. doi:10.1023/A:1025494005689.

- ^ By Richard StengerCNN.com Writer (2000-11-24). "Space - Scientists discover possible microbe from space". http://archives.cnn.com/2000/TECH/space/11/24/alien.microbe.claim/index.html. Retrieved 2009-08-20.

- ^ "Critique on Vindication of Panspermia" (PDF). Apeiron 16 (3). July 2009. http://redshift.vif.com/JournalFiles/V16NO3PDF/V16N3VAI.pdf. Retrieved 2009-11-28.

- ^ Mumbai scientist challenges theory that bacteria came from space

- ^ Janibacter hoylei sp. nov., Bacillus isronensis sp. nov. and Bacillus aryabhattai sp. nov., isolated from cryotubes used for collecting air from upper atmosphere. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 2009. http://ijs.sgmjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/ijs.0.002527-0v1

- ^ Discovery of New Microorganisms in the Stratosphere

- ^ "Apollo 12 Mission". Lunar and Planetary Institute. http://www.lpi.usra.edu/lunar/missions/apollo/apollo_12/experiments/surveyor/. Retrieved 2008-02-15.

- ^ "Apollo 12 Remembered". Astrobiology Magazine (online 21 Nov 2004). http://www.astrobio.net/exclusive/1311/apollo-12-remembered. Retrieved 2011-02-05.

- ^ Edward Anders, Eugene R. DuFresne,Ryoichi Hayatsu, Albert Cavaille, Ann DuFresne, and Frank W. Fitch. "Contaminated Meteorite," Science, New Series, Volume 146, Issue 3648 (Nov.27, 1964), 1157-1161.

- ^ Brown, Dwayne (December 2, 2010). "NASA-Funded Research Discovers Life Built With Toxic Chemical". NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/topics/universe/features/astrobiology_toxic_chemical.html.

- ^ Pennisi, Elizabeth (December 20, 2010). "Exclusive Interview (with Felisa Wolfe-Simon): Discoverer of Arsenic Bacteria, in the Eye of the Storm". Science. http://news.sciencemag.org/sciencenow/2010/12/arsenic-researcher-asks-for-time.html.

- ^ Branson, Ken (August 6, 2007). "Locked in Glaciers, Ancient Microbes May Return to Life". Rutgers Office of Media Relations. http://ur.rutgers.edu/medrel/viewArticle.html?ArticleID=5898.

- ^ "Science/Nature | Worms survived Columbia disaster". BBC News. 2003-05-01. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/2992123.stm. Retrieved 2009-08-20.

- ^ "VENUS ATMOSPHERE BUILD-UP AND EVOLUTION : WHERE DID THE OXYGEN GO?". University of Idaho. http://www.mrc.uidaho.edu/~atkinson/IPPW-3/Manuscripts/session_5_Venus_Special_Topics/42_Chassefiere_paper.pdf.

- ^ "Experiencing Venus: Clues to the Origin, Evolution, and Chemistry of Terrestrial Planets via In-Situ Exploration of our Sister World". University of Michigan. http://www-personal.umich.edu/~atreya/Chapters/Venus_AGU_Monograph_2008.pdf.

- ^ Gold, T. "Cosmic Garbage," Air Force and Space Digest, 65 (May 1960).

- ^ "Anticipating an RNA world. Some past speculations on the origin of life: where are they today?" by L. E. Orgel and F. H. C. Crick in FASEB J. (1993) Volume 7 pages 238-239.

- ^ Mautner, Michael Noah Ph.D. (2000). Seeding the Universe with Life: Securing our Cosmological Future. Legacy Books (www.amazon.com). ISBN 047600330X.

- ^ "Foton-M3 experiments return to Earth". http://www.esa.int/esaCP/SEMFVO6H07F_index_0.html. Retrieved 2007-09-26.

- ^ NASA Collaborates With Russia On Foton-M3 Mission Sep 12, 2007.

- ^ "LIFE Experiment". Planetary.org. http://www.planetary.org/programs/projects/life/. Retrieved 2009-08-20.

- ^ "Living interplanetary flight experiment: an experiment on survivability of microorganisms during interplanetary transfer" (PDF). http://www.lpi.usra.edu/meetings/phobosdeimos2007/pdf/7043.pdf. Retrieved 2009-08-20.

- Crick F, 'Life, Its Origin and Nature', Simon and Schuster, 1981, ISBN 0-7088-2235-5

- Hoyle F, 'The Intelligent Universe', Michael Joseph Limited, London 1983, ISBN 0-7181-2298-4

Further reading

- Nature News. doi:10.1038/news040216-20.

- Warmflash, D.; Weiss, B. (24 October 2005). "Did Life Come from Another Planets?". Scientific American. http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=did-life-come-from-anothe.

External links

- Francis Crick's notes for a lecture on directed panspermia, dated 5 November 1976.

|

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||