Paleosalinity

Paleosalinity is the salinity of the global ocean or of an ocean basin at a point in geological history.

Contents |

Importance

From Bjerrum plots, it is found that a decrease in the salinity of an aqueous fluid will act to increase the value of the carbon dioxide-carbonate system equilibrium constants, (pK*). This means that the relative proportion of carbonate with respect to carbon dioxide is higher in more salinity fluids, e.g. seawater, than in fresher waters. Of crucial importance for paleoclimatology is the observation that an increase in salinity will thus reduce the solubility of carbon dioxide in the oceans. Since there is thought to have been a 120m depression in sea level at the last glacial maximum due to the extensive formation of ice sheets (which are solely freshwater), this represents a significant fractionation towards saltier seas during glacial periods. Correspondingly, this will cause a net outgassing of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere because of its reduced solubility, acting to increase atmospheric carbon dioxide by 6.5‰. This is thought to partly offset the net decrease of 80-100‰ observed during glacial periods.[1]

Stratification

In addition, it is thought that extensive salinity stratification can lead to a reduction in the meridional overturning circulation (MOC) through the slowing of thermohaline circulation. Increased stratification means that there is effectively a barrier to subduction of parcels of water; isopycnals effectively do no outcrop at the surface and are parallel to the surface. The ocean, in this case, can be described as "less ventilated", and this has been implicated in the slowing down of the MOC.

Measuring Paleosalinity

There may exist proxies for salinity, but to date the main way that salinity has been measured has been by directly measuring chlorinity in pore fluids.[2] Adkins et al. (2002) used pore fluid chlorinity in ODP cores, with the paleo-depth estimated from nearby coral horizons. Chlorinity was measured rather than pure salinity because the major ions in seawater are not constant with depth in the sediment column; for example, sulphate reduction and cation-clay interactions can change overall salinity, whereas chlorinity is not heavily affected.

Paleosalinity during the Last Glacial Maximum

Adkins' study found that global salinity was greater, more or less as expected for a global sea level drop of 120m. By also analysing delta - O18 values, they also found that deep waters were within error of the freezing point of water, with oceanic waters exhibiting a greater degree of homogeneity in their temperatures. In contrast, variations in salinity were much greater than they are today. Modern day salinities are all within 0.5 psu of the global average salinity of 34.7 psu, whereas salinities during the last glacial maximum (LGM) ranged from 35.8 psu in the North Atlantic to 37.1 in the Southern Ocean.

There are some notable differences in the hydrography at the LGM and present day. Today the North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW) is observed to be more saline than Antarctic Bottom Water (AABW), whereas at the last glacial maximum it was observed that the AABW was in fact more saline; a complete reversal. Today the NADW is more salty because of the Gulf Stream; this could thus indicate a reduction of flow through the Florida Straits due to lowered sea level.

Another observation is that the Southern Ocean was vastly more salty at the LGM than today, and noticeably more salty. This is particularly intriguiging given the assumed importance of the Southern Ocean in oceanic dynamical regulation of ice ages. The extreme value of 37.1 psu is assumed to be a consequence of an increased degree of sea ice formation and export. This would account for the increased salinity, but would also account for the lack of oxygen isotopic fractionation; brine rejection without oxygen isotopic fractionation is thought to be highly characteristic of sea ice formation.

The increased role of salinity

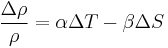

The presence of waters near the freezing point alters the balance of the relative effects of contrasts in salinity and temperature on sea water density. This is described in the equation,

where  is the thermal expansion coefficient and

is the thermal expansion coefficient and  is the haline contraction coefficient. In particular, the ratio

is the haline contraction coefficient. In particular, the ratio  is crucial. Using the observed temperatures and salinities, in the modern ocean,

is crucial. Using the observed temperatures and salinities, in the modern ocean,  is about 10 whilst at the LGM

is about 10 whilst at the LGM  it is estimated to have been closer to 25. The modern thermohaline circulation is thus more controlled by density contrasts due to thermal differences, whereas during the LGM the oceans were more than twice as sensitive to differences in salinity rather than temperature. In this way, the thermohaline circulation can be considered to have been less "thermo" and more "haline".

it is estimated to have been closer to 25. The modern thermohaline circulation is thus more controlled by density contrasts due to thermal differences, whereas during the LGM the oceans were more than twice as sensitive to differences in salinity rather than temperature. In this way, the thermohaline circulation can be considered to have been less "thermo" and more "haline".

See also

References

- ^ Sigman, D.M.; E.A. Boyle (2000). "Glacial/interglacial variations in Carbon Dioxide" (PDF). Nature 407 (6806): 859–869. doi:10.1038/35038000. PMID 11057657. http://www.up.ethz.ch/education/biogeochem_cycles/reading_list/sigman_nat_00.pdf. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ^ Adkins, J.F.; McIntyre, K. and Schrag, D.P. (2002). "The Salinity, Temperature, and delta 18O of the Glacial Deep Ocean" (PDF). Science 298 (5599): 1769–73. Bibcode 2002Sci...298.1769A. doi:10.1126/science.1076252. PMID 12459585. http://schraglab.unix.fas.harvard.edu/publications/CV49.pdf. Retrieved 2010-05-17.