PostScript

| Paradigm(s) | multi-paradigm: stack-based, procedural |

|---|---|

| Appeared in | 1982 |

| Designed by | John Warnock & Chuck Geschke |

| Developer | Adobe Systems |

| Stable release | PostScript 3 (1997) |

| Typing discipline | dynamic, strong |

| Major implementations | Adobe PostScript, TrueImage, Ghostscript, InterPress |

| Influenced by | Lisp |

| Influenced | |

| Filename extension | .ps |

|---|---|

| Internet media type | application/postscript |

| Uniform Type Identifier | com.adobe.postscript |

| Magic number | %! |

| Developed by | Adobe Systems |

| Type of format | printing file format |

| Extended to | Encapsulated PostScript |

PostScript (PS) is a dynamically typed concatenative programming language created by John Warnock and Charles Geschke in 1982. It is best known for its use as a page description language in the electronic and desktop publishing areas.

Contents |

History

The concepts of the PostScript language were seeded in 1976 when John Warnock was working at Evans & Sutherland, a computer graphics company. At that time John Warnock was developing an interpreter for a large three-dimensional graphics database of New York harbor. Warnock conceived the Design System language to process the graphics.

Concurrently, researchers at Xerox PARC had developed the first laser printer and had recognized the need for a standard means of defining page images. In 1975-76 Bob Sproull and William Newman developed the Press format, which was eventually used in the Xerox Star system to drive laser printers. But Press, a data format rather than a language, lacked flexibility, and PARC mounted the InterPress effort to create a successor.

In 1978 Evans and Sutherland asked Warnock to move from the San Francisco Bay Area to their main headquarters in Utah, but he was not interested in moving. He then joined Xerox PARC to work with Martin Newell. They rewrote Design System to create JaM (for "John and Martin") which was used for VLSI design and the investigation of type and graphics printing. This work later evolved and expanded into the InterPress language.

Warnock left with Chuck Geschke and founded Adobe Systems in December 1982. They created a simpler language, similar to InterPress, called PostScript, which went on the market in 1984. At about this time they were visited by Steve Jobs, who urged them to adapt PostScript to be used as the language for driving laser printers.

In March 1985, the Apple LaserWriter was the first printer to ship with PostScript, sparking the desktop publishing (DTP) revolution in the mid-1980s. The combination of technical merits and widespread availability made PostScript a language of choice for graphical output for printing applications. For a time an interpreter (sometimes referred to as a RIP for Raster Image Processor) for the PostScript language was a common component of laser printers, into the 1990s.

However, the cost of implementation was high; computers output raw PS code that would be interpreted by the printer into a raster image at the printer's natural resolution. This required high performance microprocessors and ample memory. The LaserWriter used a 12 MHz Motorola 68000, making it faster than any of the Macintosh computers it attached to. When the laser printer engines themselves cost over a thousand dollars the added cost of PS was marginal. But as printer mechanisms fell in price, the cost of implementing PS became an increasingly greater percentage of the overall printer cost, and thus it succumbed to cost competition in the lower-priced market tiers.

Once the de facto standard for electronic distribution of final documents meant for publication, PostScript is steadily being supplanted in this area by one of its own descendants, the Portable Document Format or PDF. By 2001 there were fewer printer models which came with support for PostScript, largely due to the growing competition from much cheaper non-PostScript ink jet printers, and new software-based methods to render PostScript images on the computer, making them suitable for any printer (PDF provided one such method). The use of a PostScript laser printer still can, however, significantly reduce the CPU workload involved in printing documents, transferring the work of rendering PostScript images from the computer to the printer. PostScript is still an option on most "high end" models.

PostScript Level 1

The first version of the PostScript language was released to the market in 1984.

PostScript Level 2

PostScript Level 2 was introduced in 1991, and included several improvements: improved speed and reliability, support for in-RIP separations, image decompression (for example, JPEG images could be rendered by a PostScript program), support for composite fonts, and the form mechanism for caching reusable content.

PostScript 3

PostScript 3 (Adobe dropped the "level" terminology in favor of simple versioning) came at the end of 1997, and along with many new dictionary-based versions of older operators, introduced better color handling, and new filters (which allow in-program compression/decompression, program chunking, and advanced error-handling).

PostScript 3 was significant in terms of replacing the existing proprietary color electronic prepress systems, then widely used for magazine production, through the introduction of smooth shading operations with up to 4096 shades of grey (rather than the 256 available in PostScript 2), as well as DeviceN, a color space that allowed the addition of additional ink colors (called spot colors) into composite color pages.

Use in printing

Before PostScript

Prior to the introduction of PostScript, printers were designed to print character output given the text—typically in ASCII—as input. There were a number of technologies for this task, but most shared the property that the glyphs were physically difficult to change, as they were stamped onto typewriter keys, bands of metal, or optical plates.

This changed to some degree with the increasing popularity of dot matrix printers. The characters on these systems were drawn as a series of dots, as defined by a font table inside the printer. As they grew in sophistication, dot matrix printers started including several built-in fonts from which the user could select, and some models allowed users to upload their own custom glyphs into the printer.

Dot matrix printers also introduced the ability to print raster graphics. The graphics were interpreted by the computer and sent as a series of dots to the printer using a series of escape sequences. These printer control languages varied from printer to printer, requiring program authors to create numerous drivers.

Vector graphics printing was left to special-purpose devices, called plotters. Almost all plotters did share a common command language, HPGL, but were of limited use for anything other than printing graphics. In addition, they tended to be expensive and slow, and thus rare.

PostScript printing

Laser printers combine the best features of both printers and plotters. Like plotters, laser printers offer high quality line art, and like dot-matrix printers, they are able to generate pages of text and raster graphics. Unlike either printers or plotters, however, a laser printer makes it possible to position high-quality graphics and text on the same page. PostScript made it possible to fully exploit these characteristics, by offering a single control language that could be used on any brand of printer.

PostScript went beyond the typical printer control language and was a complete programming language of its own. Many applications can transform a document into a PostScript program whose execution will result in the original document. This program can be sent to an interpreter in a printer, which results in a printed document, or to one inside another application, which will display the document on-screen. Since the document-program is the same regardless of its destination, it is called device-independent.

PostScript is noteworthy for implementing on-the fly rasterization; everything, even text, is specified in terms of straight lines and cubic Bézier curves (previously found only in CAD applications), which allows arbitrary scaling, rotating and other transformations. When the PostScript program is interpreted, the interpreter converts these instructions into the dots needed to form the output. For this reason PostScript interpreters are also sometimes called PostScript Raster Image Processors, or RIPs.

Font handling

Almost as complex as PostScript itself was its handling of fonts. The rich font system used the PS graphics primitives to draw glyphs as line art, which could then be rendered at any resolution. Though this sounds like a reasonably straightforward concept, there were a number of typographic issues that had to be considered.

One issue is that fonts do not actually scale linearly at small sizes; features of the glyphs will become proportionally too large or small and they start to look wrong. PostScript avoided this problem with the inclusion of hints which could be saved along with the font outlines. Basically they are additional information in horizontal or vertical bands that help identify the features in each letter that are important for the rasterizer to maintain. The result was significantly better-looking fonts even at low resolution; it had formerly been believed that hand-tuned bitmap fonts were required for this task.

At the time, the technology for including these hints in fonts was carefully guarded, and the hinted fonts were compressed and encrypted into what Adobe called a Type 1 Font (also known as PostScript Type 1 Font, PS1, T1 or Adobe Type 1). Type 1 was effectively a simplification of the PS system to store outline information only, as opposed to being a complete language (PDF is similar in this regard). Adobe would then sell licenses to the Type 1 technology to those wanting to add hints to their own fonts. Those who did not license the technology were left with the Type 3 Font (also known as PostScript Type 3 Font, PS3 or T3). Type 3 fonts allowed for all the sophistication of the PostScript language, but without the standardized approach to hinting. Other differences further added to the confusion.

Type 2 was designed to be used with the Compact Font Format (CFF), and were implemented for a compact representation of the glyph description procedures to reduce the overall font file size. The CFF/Type2 format later became the basis for Type 1 OpenType fonts.

CID-keyed font format was also designed, to solve the problems in the OCF/Type 0 fonts, for addressing the complex Asian-language (CJK) encoding and very large character set issues. CID-keyed font format can be used with the Type 1 font format for standard CID-keyed fonts, or Type 2 for CID-keyed OpenType fonts.

Adobe's rates were widely considered to be prohibitively high, and it was this issue that led Apple to design their own system, TrueType, around 1991. Immediately following the announcement of TrueType, Adobe published the specification for the Type 1 font format. Retail tools such as Altsys Fontographer (acquired by Macromedia in January 1995, owned by FontLab since May 2005) added the ability to create Type 1 fonts. Since then, many free Type 1 fonts have been released; for instance, the fonts used with the TeX typesetting system are available in this format.

In the early 1990s there were several other systems for storing outline-based fonts, developed by Bitstream and METAFONT for instance, but none included a general-purpose printing solution and they were therefore not widely used.

In the late 1990s, Adobe joined Microsoft in developing OpenType, essentially a functional superset of the Type 1 and TrueType formats. When printed to a PostScript output device, the unneeded parts of the OpenType font are omitted, and what is sent to the device by the driver is the same as it would be for a TrueType or Type 1 font, depending on which kind of outlines were present in the OpenType font.

Other implementations

In the 1980s, Adobe drew most of its revenue from the licensing fees for their implementation of PostScript for printers, known as a raster image processor or RIP. As a number of new RISC-based platforms became available in the mid 1980s, some found Adobe's support of the new machines to be lacking.

This and issues of cost led to third-party implementations of PostScript becoming common, particularly in low-cost printers (where the licensing fee was the sticking point) or in high-end typesetting equipment (where the quest for speed demanded support for new platforms faster than Adobe could provide). At one point, Microsoft and Apple teamed up to try to unseat Adobe's laser printer monopoly, Microsoft licensing to Apple a PostScript-compatible interpreter it had bought called TrueImage, and Apple licensing to Microsoft its new font format, TrueType. (Apple ended up reaching an accord with Adobe and licensed genuine PostScript for its printers, but TrueType became the standard outline font technology for both Windows and the Macintosh.)

Today, third-party PostScript-compatible interpreters are widely used in printers and multifunction peripherals (MFPs). For example, CSR plc's IPS PS3[1] interpreter, formerly known as PhoenixPage, is standard in many printers and MFPs, including those developed by Hewlett-Packard and sold under the LaserJet and Color LaserJet lines. Other third-party PostScript solutions used by print and MFP manufacturers include Jaws[2] and the Harlequin RIP, both provided by Global Graphics. Several compatible interpreters are listed on the Undocumented Printing Wiki.[3]

Still, some basic, inexpensive laser printers don't support PostScript, instead coming with drivers that simply rasterize the platform's native graphics formats rather than converting them to PostScript first. When PostScript support is needed for such a printer, a free PostScript-compatible interpreter called Ghostscript can be used. Ghostscript prints PostScript documents on non-PostScript printers using the CPU of the host computer to do the rasterization, sending the result as a single large bitmap to the printer. Ghostscript can also be used to preview PostScript documents on a computer monitor and to convert PostScript pages into raster graphics such as TIFF and PNG, and vector formats such as PDF. There are a number of commercial PostScript interpreters also, such as TeletypeSetting Co.'s T-Script.

Very high-resolution devices, such as imagesetters or CTP platesetters, in which resolutions exceeding 2500 dpi are common, still require external RIPs with large amounts of memory and hard drive space. Very high-end laser printer systems (known as digital presses) also use an external RIP to separate the more readily-upgradable computer from the specialized printing hardware. Companies such as EFI and Xitron specialize in such RIP software.

Use as a display system

PostScript became commercially successful due to the introduction of the graphical user interface, allowing designers to directly lay out pages for eventual output on laser printers. However, the GUI's own graphics systems were generally much less sophisticated than PostScript; Apple's QuickDraw, for instance, supported only basic lines and arcs, not the complex B-splines and advanced region filling options of PostScript. In order to take full advantage of PostScript printing, applications on the computers had to re-implement those features using the host platform's own graphics system. This led to numerous issues where the on-screen layout would not exactly match the printed output, due to differences in the implementation of these features.

As computer power grew, it became possible to host the PS system in the computer rather than the printer. This led to the natural evolution of PS from a printing system to one that could also be used as the host's own graphics language. There were numerous advantages to this approach; not only did it help eliminate the possibility of different output on screen and printer, but it also provided a powerful graphics system for the computer, and allowed the printers to be "dumb" at a time when the cost of the laser engines was falling. In a production setting, using PostScript as a display system meant that the host computer could render low-resolution to the screen, higher resolution to the printer, or simply send the PS code to a smart printer for offboard printing.

However, PostScript was written with printing in mind, and had numerous features that made it unsuitable for direct use in an interactive display system. In particular, PS was based on the idea of collecting up PS commands until the showpage command was seen, at which point all of the commands read up to that point were interpreted and output. In an interactive system this was clearly not appropriate. Nor did PS have any sort of interactivity built in; for example, supporting hit detection for mouse interactivity obviously did not apply when PS was being used on a printer.

When Steve Jobs left Apple and started NeXT, he pitched Adobe on the idea of using PS as the display system for his new workstation computers. The result was Display PostScript, or DPS. DPS added basic functionality to improve performance by changing many string lookups into 32 bit integers, adding support for direct output with every command, and adding functions to allow the GUI to inspect the diagram. Additionally, a set of "bindings" was provided to allow PS code to be called directly from the C programming language. NeXT used these bindings in their NeXTStep system to provide an object oriented graphics system. Although DPS was written in conjunction with NeXT, Adobe sold it commercially and it was a common feature of most Unix workstations in the 1990s.

Sun Microsystems took another approach, creating NeWS. Instead of DPS's concept of allowing PS to interact with C programs, NeWS instead extended PS into a language suitable for running the entire GUI of a computer. Sun added a number of new commands for timers, mouse control, interrupts and other systems needed for interactivity, and added data structures and language elements to allow it to be completely object oriented internally. A complete GUI, three in fact, were written in NeWS and provided for a time on their workstations. However, the ongoing efforts to standardize the X11 system led to its introduction and widespread use on Sun systems, and NeWS never became widely used.

The language

PostScript is a Turing-complete programming language, belonging to the concatenative group. Typically, PostScript programs are not produced by humans, but by other programs. However, it is possible to write computer programs in PostScript just like any other programming language.

PostScript is an interpreted, stack-based language similar to Forth but with strong dynamic typing, data structures inspired by those found in Lisp, scoped memory and, since language level 2, garbage collection. The language syntax uses reverse Polish notation, which makes the order of operations unambiguous, but reading a program requires some practice, because one has to keep the layout of the stack in mind. Most operators (what other languages term functions) take their arguments from the stack, and place their results onto the stack. Literals (for example, numbers) have the effect of placing a copy of themselves on the stack. Sophisticated data structures can be built on the array and dictionary types, but cannot be declared to the type system, which sees them all only as arrays and dictionaries, so any further typing discipline to be applied to such user-defined "types" is left to the code that implements them.

The character "%" is used to introduce comments in PostScript programs. As a general convention, every PostScript program should start with the characters "%!" as an interpreter directive so that all devices will properly interpret it as PostScript.

"Hello world"

A Hello World program, the customary way to show a small example of a complete program in a given language, might look like this in PostScript (level 2):

%!PS

/Courier % name the desired font

20 selectfont % choose the size in points and establish

% the font as the current one

72 500 moveto % position the current point at

% coordinates 72, 500 (the origin is at the

% lower-left corner of the page)

(Hello world!) show % stroke the text in parentheses

showpage % print all on the page

or if the output device has a console

%!PS (Hello world!) =

Units of length

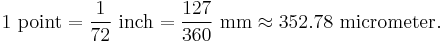

Postscript uses the point as its unit of length. However, unlike some of the other versions of the point, PostScript uses exactly 72 points to the inch. Thus:

For example, in order to draw a vertical line of 4 cm length, it is sufficient to type:

0 0 moveto 0 113.385827 lineto stroke

More readably and idiomatically, one might use the following equivalent, which demonstrates a simple procedure definition and the use of the mathematical operators mul and div:

/mm { 360 mul 127 div } def

0 0 moveto

0 40 mm lineto stroke

In most implementations PostScript uses single-precision reals (24-bit mantissa), so it is not meaningful to use more than 9 decimal digits to specify a real number, and performing calculations may produce unacceptable round-off errors.

See also

- Adobe Systems

- Ghostscript

- Portable Document Format

- Document Structuring Conventions

- Vector graphics

- Typeface

- Computer font

- Encapsulated PostScript

- Reverse Polish notation

- PostScript Printer Description

- InterPress

- PCL

- TeX

- LaTeX

Notes

References

This article was originally based on material from the Free On-line Dictionary of Computing, which is licensed under the GFDL.

External links

- PostScript Language Reference, third edition (PLR3), plus its Supplement, is the de facto defining work, known as "The Red Book" on account of its covers. The first edition covered PostScript Level 1, the second edition covered a greatly expanded language known as PostScript Level 2, and includes documentation for Display PostScript as well. The third edition covers PostScript 3 (with this version, Adobe dropped "level" from the name) but no longer includes DPS.

- PostScript Language Tutorial and Cookbook is the corresponding introductory text, known as "The Blue Book" on account of its covers.

- PostScript language program design is "The Green Book".

- Adobe: PostScript vs. PDF - Official introductory comparison of PS, EPS vs. PDF.

- Adobe: The Type 1 Font Format (PDF file).

- A First Guide to PostScript

- Mathematical Illustrations: A Manual of Geometry and PostScript — a book by Bill Casselman.

- Mathematical Illustrations: A Manual of Geometry and PostScript — a book by Bill Casselman (PDF file).

- Thinking in PostScript - 1990 by Glenn Reid, Addison-Wesley — A thorough tutorial available online courtesy of the author.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||