Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider

The Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider at Brookhaven National Laboratory. Note especially the second, independent ring behind the blue striped one. Barely visible and between the white and red pipes on the left wall, is the orange Crash Cord, which should be used to stop the beam in case a person is still left in the tunnel. |

|

| Intersecting Storage Rings | CERN, 1971–1984 |

|---|---|

| Super Proton Synchrotron | CERN, 1981–1984 |

| ISABELLE | BNL, cancelled in 1983 |

| Tevatron | Fermilab, 1987–2011 |

| Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider | BNL, 2000–present |

| Superconducting Super Collider | Cancelled in 1993 |

| Large Hadron Collider | CERN, 2009–present |

| Super Large Hadron Collider | Proposed, CERN, 2019– |

| Very Large Hadron Collider | Theoretical |

The Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC, /ˈrɪk/) is a heavy-ion collider and a spin-polarized proton collider. It is located at Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL) in Upton, New York and operated by an international team of researchers.[1][2][3] By using RHIC to collide ions traveling at relativistic speeds, physicists study the primordial form of matter that existed in the universe shortly after the Big Bang.[4][5] By colliding spin-polarized protons, the spin structure of the proton is explored.

RHIC is now the second-highest-energy heavy-ion collider in the world. As of 7 November 2010, the LHC has collided heavy ions of lead at higher energies than RHIC.[6]

In 2010, RHIC physicists published results of temperature measurements from earlier experiments which concluded that temperatures in excess of 4 trillion kelvins (7 trillion degrees Fahrenheit) had been achieved in gold ion collisions, and that these collision temperatures resulted in the breakdown of "normal matter" and the creation of a liquid-like quark-gluon plasma.[7]

Contents |

The accelerator

RHIC is an intersecting storage ring particle accelerator. Two independent rings (arbitrarily denoted as "Blue" and "Yellow" rings, see also the photograph) circulate heavy ions and/or protons in opposite directions and allow a virtually free choice of colliding positively charged particles (the eRHIC upgrade will allow collisions between positively and negatively charged particles). The RHIC double storage ring is itself hexagonally shaped and 3,834 m long in circumference, with curved edges in which stored particles are deflected and focused by 1,740 superconducting niobium-titanium magnets. The dipole magnets operate at 3.45 T.[8] The six interaction points (between the particles circulating in the two rings) are at the middle of the six relatively straight sections, where the two rings cross, allowing the particles to collide. The interaction points are enumerated by clock positions, with the injection near 6 o'clock. Two large experiments, STAR and PHENIX, are located at 6 and 8 o'clock respectively.[9]

A particle passes through several stages of boosters before it reaches the RHIC storage ring. The first stage for ions is the Tandem Van de Graaff accelerator, while for protons, the 200 MeV linear accelerator (Linac) is used. As an example, gold nuclei leaving the Tandem Van de Graaff have an energy of about 1 MeV per nucleon and have an electric charge Q = +31 (31 of 79 electrons stripped from the gold atom). The particles are then accelerated by the Booster Synchrotron to 95 MeV per nucleon, which injects the projectile now with Q = +77 into the Alternating Gradient Synchrotron (AGS), before they finally reach 8.86 GeV per nucleon and are injected in a Q = +79 state (no electrons left) into the RHIC storage ring over the AGS-to-RHIC Transfer Line (ATR).

The main types of particle combinations explored at RHIC are p + p, d + Au, Cu + Cu and Au + Au. The projectiles typically travel at a speed of 99.995% of the speed of light. For Au + Au collisions, the center-of-mass energy is typically 200 GeV (or 100 GeV per nucleon); an average luminosity of 2×1026 cm−2s−1 was targeted during the planning. The current average luminosity of the collider is 20×1026 cm−2s−1, 10 times the design value.[10] For polarized p + p collision, Run-9 achieved center-of-mass energy of 500 GeV on 12 February 2009.[11]

One unique characteristic of RHIC is its capability to produce polarized protons. RHIC holds the record of highest energy polarized protons. Polarized protons are injected into RHIC and preserve this state throughout the energy ramp. This is a difficult task that can only be accomplished with the aid of Siberian snakes (a chain of solenoids and quadrupoles for aligning particles) and AC dipoles.[12][13] The AC dipoles have been also used in non-linear machine diagnostics for the first time in RHIC.[14]

The experiments

There are four detectors at RHIC: STAR (6 o'clock, and near the AGS-to-RHIC Transfer Line), PHENIX (8 o'clock), PHOBOS (10 o'clock), and BRAHMS (2 o'clock). Two of them are still active, with PHOBOS having completed its operation after 2005 and Run-05, and BRAHMS after 2006 and Run-06.

Among the two larger detectors, STAR is aimed at the detection of hadrons with its system of time projection chambers covering a large solid angle and in a conventionally generated solenoidal magnetic field, while PHENIX is further specialized in detecting rare and electromagnetic particles, using a partial coverage detector system in a superconductively generated axial magnetic field. The smaller detectors have larger pseudorapidity coverage, PHOBOS has the largest pseudorapidity coverage of all detectors, and tailored for bulk particle multiplicity measurement, while BRAHMS is designed for momentum spectroscopy, in order to study the so called "small-x" and saturation physics. There is an additional experiment, PP2PP, investigating spin dependence in p + p scattering.[15]

The spokespersons for each of the experiments are:

- STAR: Nu Xu (Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory, Nuclear Science Division)

- PHENIX: Barbara Jacak (Stony Brook University, Department of Physics and Astronomy)

- PHOBOS: Wit Busza (Massachusetts Institute of Technology Department of Physics and MIT Laboratory for Nuclear Science)

- BRAHMS: Flemming Videbaek (Brookhaven National Laboratory, Physics Department)

- PP2PP: Włodek Guryn (Brookhaven National Laboratory, Physics Department)

Current results

For a complementary discussion, see also quark-gluon plasma.

For the experimental objective of creating and studying the quark-gluon plasma, RHIC has the unique ability to provide baseline measurements for itself. This consists of the both lower energy and also lower mass number projectile combinations that do not result in the density of 200 GeV Au + Au collisions, like the p + p and d + Au collisions of the earlier runs, and also Cu + Cu collisions in Run-5.

Using this approach, important results of the measurement of the hot QCD matter created at RHIC are:[16]

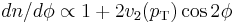

- Collective anisotropy, or elliptic flow. The multiplicity of the particles' bulk with lower momenta exhibits a dependency as

(pT is the transverse momentum,

(pT is the transverse momentum,  angle with the reaction plane). This is a direct result of the elliptic shape of the nucleus overlap region during the collision and hydrodynamical property of the matter created.

angle with the reaction plane). This is a direct result of the elliptic shape of the nucleus overlap region during the collision and hydrodynamical property of the matter created.

- Jet quenching. In the heavy ion collision event, scattering with a high transverse pT can serve as a probe for the hot QCD matter, as it loses its energy while traveling through the medium. Experimentally, the quantity RAA (A is the mass number) being the quotient of observed jet yield in A + A collisions and Nbin × yield in p + p collisions shows a strong damping with increasing A, which is an indication of the new properties of the hot QCD matter created.

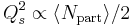

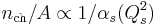

- Color glass condensate saturation. The Balitsky–Fadin–Kuraev–Lipatov (BFKL) dynamics[17] which are the result of a resummation of large logarithmic terms in Q² for deep inelastic scattering with small Bjorken-x, saturate at a unitarity limit

, with Npart/2 being the number of participant nucleons in a collision (as opposed to the number of binary collisions). The observed charged multiplicity follows the expected dependency of

, with Npart/2 being the number of participant nucleons in a collision (as opposed to the number of binary collisions). The observed charged multiplicity follows the expected dependency of  , supporting the predictions of the color glass condensate model. For a detailed discussion, see e.g. Kharzeev et al.;[18] for an overview of color glass condensates, see e.g. Iancu & Venugopalan.[19]

, supporting the predictions of the color glass condensate model. For a detailed discussion, see e.g. Kharzeev et al.;[18] for an overview of color glass condensates, see e.g. Iancu & Venugopalan.[19]

- Particle ratios. The particle ratios predicted by statistical models allow the calculation of parameters such as the temperature at chemical freeze-out Tch and hadron chemical potential

. The experimental value Tch varies a bit with the model used, with most authors giving a value of 160 MeV < Tch < 180 MeV, which is very close to the expected QCD phase transition value of approximately 170 MeV obtained by lattice QCD calculations (see e.g. Karsch[20]).

. The experimental value Tch varies a bit with the model used, with most authors giving a value of 160 MeV < Tch < 180 MeV, which is very close to the expected QCD phase transition value of approximately 170 MeV obtained by lattice QCD calculations (see e.g. Karsch[20]).

While in the first years, theorists were eager to claim that RHIC has discovered the quark-gluon plasma (e.g. Gyulassy & McLarren[21]), though the experimental groups were more careful not to jump to conclusions, citing various variables still in need of further measurement.[22] The present results shows that the matter created is a fluid with a viscosity near the quantum limit, but is unlike a weakly interacting plasma (a widespread yet not quantitatively unfounded belief on how quark gluon plasma looks).

A recent overview of the physics result is provided by the RHIC Experimental Evaluations 2004, a community-wide effort of RHIC experiments to evaluate the current data in the context of implication for formation of a new state of matter.[23] These results are from the first three years of data collection at RHIC.

New results were published in Physical Review Letters on February 16, 2010, stating the discovery of the first hints of symmetry transformations, and that the observations may suggest that bubbles formed in the aftermath of the collisions created in the RHIC may break parity symmetry, which normally characterizes interactions between quarks and gluons.[24][25]

The RHIC physicists announced new temperature measurements for these experiments of up to 7.2 trillion kelvins, the highest temperature ever achieved in a laboratory.[26] It is described as a recreation of the conditions that existed during the birth of the Universe.[27]

The future

RHIC began operation in 2000 and until November 2010 was the most powerful heavy-ion collider in the world. The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) of CERN, while used mainly for colliding protons, will operate with heavy ions for about one month per year. LHC will eventually operate 28 times higher ion energies, although current LHC operation is at half this energy.

Due to the longer operating time per year, a greater number of colliding ion species and collision energies can be studied at RHIC. In addition and unlike the LHC, RHIC is able to accelerate spin polarized protons, which would leave RHIC as the world's highest energy accelerator for studying spin-polarized proton structure.

A planned major upgrade is eRHIC: The construction of a 10 GeV high intensity electron/positron beam facility, allowing electron-ion collisions. At least one new detector will have to be built to study the collisions. A recent review is given by A. Deshpande et al..[28]

In October 2006, then Interim Director of BNL, Sam Aronson, has contested the claim in a Physics Today report that "Tevatron is unlikely to outlive the decade. Neither is ... the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider", referring to a report of the National Research Council.[29]

Critics of high energy experiments

Before RHIC started operation, critics postulated that the extremely high energy could produce catastrophic scenarios,[30] such as creating a black hole, a transition into a different quantum mechanical vacuum (see false vacuum), or the creation of strange matter that is more stable than ordinary matter. These hypotheses are complex, but many predict that the Earth would be destroyed in a time frame from seconds to millennia, depending on the theory considered. However, the fact that objects of the Solar System (e.g., the Moon) have been bombarded with cosmic particles of significantly higher energies than that of RHIC and other man made colliders for billions of years, without any harm to the Solar System, were among the most striking arguments that these hypotheses were unfounded.[31]

The other main controversial issue was a demand by critics for physicists to reasonably exclude the probability for such a catastrophic scenario. Physicists are unable to demonstrate experimental and astrophysical constraints of zero probability of catastrophic events, nor that tomorrow Earth will be struck with a "doomsday" cosmic ray (they can only calculate an upper limit for the likelihood). The result would be the same destructive scenarios described above, although obviously not caused by humans. According to this argument of upper limits, RHIC would still modify the chance for the Earth's survival by an infinitesimal amount.

Concerns were raised in connection with the RHIC particle accelerator, both in the media[32][33] and in the popular science media.[34] The risk of a doomsday scenario was indicated by Martin Rees, with respect to the RHIC, as being at least a 1 in 50,000,000 chance.[35] With regards to the production of strangelets, Frank Close, professor of physics at the University of Oxford, indicates that "the chance of this happening is like you winning the major prize on the lottery 3 weeks in succession; the problem is that people believe it is possible to win the lottery 3 weeks in succession."[36] After detailed studies, scientists reached such conclusions as "beyond reasonable doubt, heavy-ion experiments at RHIC will not endanger our planet"[37] and that there is "powerful empirical evidence against the possibility of dangerous strangelet production."[38]

The debate started in 1999 with an exchange of letters in Scientific American between Walter L. Wagner,[39] and F. Wilczek,[40] Institute for Advanced Study, in response to a previous article by M. Mukerjee.[41] The media attention unfolded with an article in U.K. Sunday Times of July 18, 1999 by J. Leake,[42] closely followed by articles in the U.S. media.[43] The controversy mostly ended with the report of a committee convened by the director of Brookhaven National Laboratory, J. H. Marburger, ostensibly ruling out the catastrophic scenarios depicted.[31] However, the report left open the possibility that relativistic cosmic ray impact products might behave differently while transiting earth compared to "at rest" RHIC products; and the possibility that the qualitative difference between high-E proton collisions with earth or the moon might be different than gold on gold collisions at the RHIC. Wagner tried subsequently to stop full energy collision at RHIC by filing Federal lawsuits in San Francisco and New York, but without success.[44] The New York suit was dismissed on the technicality that the San Francisco suit was the preferred forum. The San Francisco suit was dismissed, but with leave to refile if additional information was developed and presented to the court.[45]

On March 17, 2005, the BBC published an article[46] implying that researcher Horaţiu Năstase believes black holes have been created at RHIC. However, the original papers of H. Năstase[47] and the New Scientist article[48] cited by the BBC state that the correspondence of the hot dense QCD matter created in RHIC to a black hole is only in the sense of a correspondence of QCD scattering in Minkowski space and scattering in the AdS5 × X5 space in AdS/CFT; in other words, it is similar mathematically. Therefore, RHIC collisions might be described by mathematics relevant to theories of quantum gravity within AdS/CFT, but the described physical phenomena are not the same.

Financial information

The RHIC project is sponsored by the United States Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Nuclear Physics.[49] It had a line-item budget of 616.6 million U.S. dollars.[50] The annual operational budgets were:[51]

- fiscal year 2005: 131.6 million U.S. dollars

- fiscal year 2006: 115.5 million U.S. dollars

- fiscal year 2007, requested: 143.3 million U.S. dollars

The total investment by 2005 is approximately 1.1 billion U.S. dollars. Though operation under the fiscal year 2006 federal budget cut[52] was uncertain, a key portion of the operational cost (13 million U.S. dollars) was contributed privately by a group close to Renaissance Technologies of East Setauket, New York.[53]

RHIC in fiction

- The novel Cosm (ISBN 0-380-79052-1) by the American author Gregory Benford takes place at RHIC. The science fiction setting describes the main character Alicia Butterworth, a physicist at the BRAHMS experiment, and a new universe being created in RHIC by accident, while running with uranium ions.[54]

- The zombie apocalypse novel The Rising by the American author Brian Keene referenced the media concerns of activating the RHIC raised by the article in The Sunday Times of July 18, 1999 by J. Leake,.[42] As revealed very early in the story, side effects of the collider experiments of the RHIC (located at "Havenbrook National Laboratories") were the cause of the zombie uprising in the novel and its sequel City of the Dead.

See also

References

- ^ M. Harrison, T. Ludlam, S. Ozaki (2003). "RHIC Project Overview". Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A 499 (2–3): 235. Bibcode 2003NIMPA.499..235H. doi:10.1016/S0168-9002(02)01937-X.

- ^ M. Harrison, S. Peggs, T. Roser (2002). "The RHIC Accelerator". Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science 52: 425. Bibcode 2002ARNPS..52..425H. doi:10.1146/annurev.nucl.52.050102.090650.

- ^ E.D. Courant (2003). "Accelerators, Colliders, and Snakes". Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science 53: 1. Bibcode 2003ARNPS..53....1C. doi:10.1146/annurev.nucl.53.041002.110450.

- ^ M. Riordan, W.A. Zajc (2006). "The First Few Microseconds". Scientific American 294 (5): 34. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0506-34A. http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?articleID=0009A312-037F-1448-837F83414B7F014D.

- ^ S. Mirsky, W.A Zajc, J. Chaplin (26 April 2006). "Early Universe, Benjamin Franklin Science, Evolution Education". Science Talk. Scientific American. http://www.scientificamerican.com/podcast/episode.cfm?id=000F3F76-D5E6-144E-95E683414B7F0000. Retrieved 2010-02-16. (Listen)

- ^ "CERN Completes Transition to Lead-Ion Running at the LHC". CERN. 8 November 2010. http://press.web.cern.ch/press/PressReleases/Releases2010/PR21.10E.html. Retrieved 2010-11-08.

- ^ A. Trafton (9 February 2010). "Explained: Quark gluon plasma". MITnews. http://web.mit.edu/newsoffice/2010/exp-quark-gluon-0609.html.

- ^ P. Wanderer (22 February 2008). "RHIC". Brookhaven National Laboratory, Superconducting Magnet Division. http://www.bnl.gov/magnets/RHIC/RHIC.asp. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- ^ See "RHIC Accelerators". Brookhaven National Laboratory. http://www.bnl.gov/RHIC/complex.asp. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- ^ "RHIC Run Overview". Brookhaven National Laboratory. http://www.agsrhichome.bnl.gov/RHIC/Runs/.

- ^ "RHIC Run-9". Brookhaven National Laboratory/Alternating Gradient Synchrotron. http://www.agsrhichome.bnl.gov/AP/Spin2009/. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- ^ "Snake charming induces spin-flip". CERN Courier 42 (3): 2. 22 March 2002. http://www.cerncourier.com/main/article/42/3/2. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- ^ B.B. Blinov et al. (2002). "99.6% Spin-Flip Efficiency in the Presence of a Strong Siberian Snake". Physical Review Letters 88 (1): 014801. Bibcode 2002PhRvL..88a4801B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.014801. PMID 11800956.

- ^ R. Tomás et al. (2005). "Measurement of global and local resonance terms". Physical Review Special Topics: Accelerators and Beams 8 (2): 024001. Bibcode 2005PhRvS...8b4001T. doi:10.1103/PhysRevSTAB.8.024001.

- ^ http://www.rhic.bnl.gov/pp2pp/

- ^ T. Ludlam & L. McLerran, Phys. Today October 2003, 48 (2003).

- ^ L. N. Lipatov, Sov. J. Nucl. Phys. 23, 338 (1976).

- ^ D. Kharzeev et al., Phys. Lett. B 561, 93 (2002).

- ^ E. Iancu & R. Venugopalan, in Quark Gluon Plasma 3, edited by R. C. Hwa & X.-N. Wang, (World Scientific, Singapore, 2003), p. 249.

- ^ F. Karsch, in Lectures on Quark Matter, Lect. Notes Phys. 583 (Springer, Berlin, 2002), p. 209.

- ^ M. Gyulassy & L. McLarren, Nucl. Phys. A 750, 30 (2005).

- ^ K. McNulty Walsh, "Latest RHIC Results Make News Headlines at Quark Matter 2004", Discover Brookhaven 2:1, 14–17 (2004).

- ^ I. Arsene et al. (BRAHMS collaboration), Nucl. Phys. A 757 1, (2005); K. Adcox et al. (PHENIX Collaboration), Nucl. Phys. A 757, 184 (2005); B. B. Back et al. (PHOBOS Collaboration), Nucl. Phys. A 757, 28 (2005); J. Adams et al. (STAR Collaboration), Nucl. Phys. A 757, 102 (2005).

- ^ K. Melville (16 February 2010). "Mirror Symmetry Broken at 7 Trillion Degrees". Science a Go Go. http://www.scienceagogo.com/news/20100115233339data_trunc_sys.shtml. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- ^ D. Overbye (15 February 2010). "In Brookhaven Collider, Scientists Briefly Break a Law of Nature". New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/16/science/16quark.html. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- ^ Perfect Liquid Hot Enough to be Quark Soup

- ^ D. Vergano (16 February 2010). "Scientists Re-create High Temperatures from Big Bang". USA Today. http://www.usatoday.com/tech/science/2010-02-16-RHIC16_ST_N.htm. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- ^ A. Deshpande et al., Ann. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 55, 165 (2005).

- ^ S. Aronson, Phys. Today, October 2006, 15.

- ^ T. D. Gutierrez, "Doomsday Fears at RHIC," Skeptical Inquirer 24, 29 (May 2000)

- ^ a b R. Jaffe et al., Rev. Mod. Phys. 72, 1125–1140 (2000).

- ^ Matthews, Robert (28 August 1999). "A Black Hole Ate My Planet". New Scientist. http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg16322014.700-a-black-hole-ate-my-planet.html.

- ^ <Please add first missing authors to populate metadata.> (2005). Horizon: End Day. BBC.

- ^ W. Wagner, "Black holes at Brookhaven?" and reply by F. Wilzcek, Letters to the Editor, Scientific American July 1999

- ^ Cf. Brookhaven Report mentioned by Rees, Martin (Lord), Our Final Century: Will the Human Race Survive the Twenty-first Century?, U.K., 2003, ISBN 0-465-06862-6; note that the mentioned "1 in 50 million" chance is disputed as being a misleading and played down probability of the serious risks (Aspden, U.K., 2006)

- ^ BBC End Days (Documentary)

- ^ A. Dar, A. De Rujula, U. Heinz, "Will relativistic heavy ion colliders destroy our planet?", Phys. Lett. B470:142–148 (1999) arXiv:hep-ph/9910471

- ^ W. Busza, R. Jaffe, J. Sandweiss, F. Wilczek, "Review of speculative 'disaster scenarios' at RHIC", Rev. Mod. Phys.72:1125–1140 (2000) arXiv:hep-ph/9910333

- ^ Wagner is a lawyer and former physics lab technician. In 1975, he worked on a project that claimed to discover a magnetic monopole in cosmic ray data ("Evidence for the Detection of a Moving Magnetic Monopole", Physical Review Letters, Vol. 35, (1975)). That claim was later withdrawn in 1978 ("Further Measurements and Reassessment of the Magnetic Monopole Candidate", Physical Review D18: 1382–1421 (1978))

- ^ Wilczek is noted for his work on quarks, for which he subsequently was awarded the Nobel Prize

- ^ M. Mukerjee, Scientific American 280:March, 60 (1999). The Wagner and Wilczek letters follow in the July issue (vol. 281 no. 1), p. 8.

- ^ a b Sunday Times, 18 July 1999.

- ^ e.g. ABCNEWS.com, from the Internet Archive.

- ^ e.g. MSNBC, June 14, 2000.

- ^ United States District Court, Eastern District of New York, Case No. 00CV1672, Walter L. Wagner vs. Brookhaven Science Associates, L.L.C. (2000); United States District Court, Northern District of California, Case No. C99-2226, Walter L. Wagner vs. U.S. Department of Energy, et al. (1999)

- ^ BBC, 17 March 2005.

- ^ H. Nastase, hep-th/0501068 (2005).

- ^ E. S. Reich, New Scientist 185:2491, 16 (2005).

- ^ U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Nuclear Physics

- ^ M. Harrison, T. Ludlam, & S. Ozaki, Nucl. Instr. Meth. Phys. Res. A 499:2–3, 235 (2003).

- ^ U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Budget

- ^ e.g. FYI, November 22, 2005; New York Times, November 27, 2005.

- ^ e.g. APS News Online, March 2006; FYI, November 22, 2005.

- ^ Brookhaven Bulletin 52, 8 (1998), p. 2.

Further reading

- M. Harrison, T. Ludlam and S. Ozaki (eds) (2003). "The Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider Project: RHIC and its Detectors". Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A 499 (2–3): 235–880. Bibcode 2003NIMPA.499..235H. doi:10.1016/S0168-9002(02)01937-X. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=PublicationURL&_tockey=%23TOC%235314%232003%23995009997%23459310%23FLA%23&_cdi=5314&_pubType=J&_auth=y&_acct=C000050221&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=10&md5=0a6c6433f261a636ae8150534e4fc6ab. Preprints are available at