Operational amplifier

An operational amplifier ("op-amp") is a DC-coupled high-gain electronic voltage amplifier with a differential input and, usually, a single-ended output.[1] An op-amp produces an output voltage that is typically hundreds of thousands times larger than the voltage difference between its input terminals.[2]

Operational amplifiers are important building blocks for a wide range of electronic circuits. They had their origins in analog computers where they were used in many linear, non-linear and frequency-dependent circuits. Their popularity in circuit design largely stems from the fact that characteristics of the final op-amp circuits with negative feedback (such as their gain) are set by external components with little dependence on temperature changes and manufacturing variations in the op-amp itself.

Op-amps are among the most widely used electronic devices today, being used in a vast array of consumer, industrial, and scientific devices. Many standard IC op-amps cost only a few cents in moderate production volume; however some integrated or hybrid operational amplifiers with special performance specifications may cost over $100 US in small quantities. Op-amps may be packaged as components, or used as elements of more complex integrated circuits.

The op-amp is one type of differential amplifier. Other types of differential amplifier include the fully differential amplifier (similar to the op-amp, but with two outputs), the instrumentation amplifier (usually built from three op-amps), the isolation amplifier (similar to the instrumentation amplifier, but with tolerance to common-mode voltages that would destroy an ordinary op-amp), and negative feedback amplifier (usually built from one or more op-amps and a resistive feedback network).

Contents |

Circuit notation

The circuit symbol for an op-amp is shown to the right, where:

- V+: non-inverting input

- V−: inverting input

- Vout: output

- VS+: positive power supply

- VS−: negative power supply

The power supply pins (VS+ and VS−) can be labeled in different ways (See IC power supply pins). Despite different labeling, the function remains the same – to provide additional power for amplification of the signal. Often these pins are left out of the diagram for clarity, and the power configuration is described or assumed from the circuit.

Operation

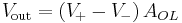

The amplifier's differential inputs consist of a V+ input and a V− input, and ideally the op-amp amplifies only the difference in voltage between the two, which is called the differential input voltage. The output voltage of the op-amp is given by the equation,

where V+ is the voltage at the non-inverting terminal, V− is the voltage at the inverting terminal and AOL is the open-loop gain of the amplifier (the term "open-loop" refers to the absence of a feedback loop from the output to the input).

The magnitude of AOL is typically very large—10,000 or more for integrated circuit op-amps—and therefore even a quite small difference between V+ and V− drives the amplifier output nearly to the supply voltage. This is called saturation of the amplifier. The magnitude of AOL is not well controlled by the manufacturing process, and so it is impractical to use an operational amplifier as a stand-alone differential amplifier. Without negative feedback, and perhaps with positive feedback for regeneration, an op-amp acts as a comparator. If the inverting input is held at ground (0 V) directly or by a resistor, and the input voltage Vin applied to the non-inverting input is positive, the output will be maximum positive; if Vin is negative, the output will be maximum negative. Since there is no feedback from the output to either input, this is an open loop circuit acting as a comparator. The circuit's gain is just the AOL< of the op-amp.

If predictable operation is desired, negative feedback is used, by applying a portion of the output voltage to the inverting input. The closed loop feedback greatly reduces the gain of the amplifier. If negative feedback is used, the circuit's overall gain and other parameters become determined more by the feedback network than by the op-amp itself. If the feedback network is made of components with relatively constant, stable values, the unpredictability and inconstancy of the op-amp's parameters do not seriously affect the circuit's performance. Typically the op-amp's very large gain is controlled by negative feedback, which largely determines the magnitude of its output ("closed-loop") voltage gain in amplifier applications, or the transfer function required (in analog computers). High input impedance at the input terminals and low output impedance at the output terminal(s) are important typical characteristics.

For example, in a non-inverting amplifier (see the figure on the right) adding a negative feedback via the voltage divider Rf,Rg reduces the gain. Equilibrium will be established when Vout is just sufficient to reach around and "pull" the inverting input to the same voltage as Vin. The voltage gain of the entire circuit is determined by 1 + Rf/Rg. As a simple example, if Vin = 1 V and Rf = Rg, Vout will be 2 V, the amount required to keep V– at 1 V. Because of the feedback provided by Rf,Rg this is a closed loop circuit. Its overall gain Vout / Vin is called the closed-loop gain ACL. Because the feedback is negative, in this case ACL is less than the AOL of the op-amp.

Another way of looking at it is to make two relatively valid assumptions: One, that when an op-amp is being operated in linear mode, the difference in voltage between the non-inverting (+) pin and the inverting (-) pin is so small as to be considered negligible.[3] The second assumption is that the input impedance at both + and - pins is extremely high (at least several megaohms with modern op-amps). Thus, when the circuit to the right is operated as a non-inverting linear amplifier, Vin will appear at the + and - pins and create a current i through Rg equal to Vin/Rg. Since Kirchoff's current law states that the same current must leave a node as enter it, and since the impedance into the - pin is near infinity, we can assume the overwhelming majority of the same current i travels through Rf, creating an output voltage equal to Vin + i*Rf. By combining terms, we can easily determine the gain of this particular type of circuit.

i = Vin / Rg

Vout = Vin + i*Rf

Vout = Vin + (Vin / Rg) * Rf

Vout = Vin + (Vin * Rf) / Rg

G = Vout/Vin = (Vin + (Vin * Rf) / Rg) / Vin

G = (Vin/Vin) + (Vin * Rf) / Rg) / Vin

G = 1 + (Vin * Rf) / (Rg * Vin)

G = 1 + Rf/Rg

Op-amp characteristics

Ideal op-amps

An ideal op-amp is usually considered to have the following properties, and they are considered to hold for all input voltages:

- Infinite open-loop gain (when doing theoretical analysis, a limit may be taken as open loop gain AOL goes to infinity).

- Infinite voltage range available at the output (

) (in practice the voltages available from the output are limited by the supply voltages

) (in practice the voltages available from the output are limited by the supply voltages  and

and  ). The power supply sources are called rails.

). The power supply sources are called rails. - Infinite bandwidth (i.e., the frequency magnitude response is considered to be flat everywhere with zero phase shift).

- Infinite input impedance (so, in the diagram,

, and zero current flows from

, and zero current flows from  to

to  ).

). - Zero input current (i.e., there is assumed to be no leakage or bias current into the device).

- Zero input offset voltage (i.e., when the input terminals are shorted so that

, the output is a virtual ground or

, the output is a virtual ground or  ).

). - Infinite slew rate (i.e., the rate of change of the output voltage is unbounded) and power bandwidth (full output voltage and current available at all frequencies).

- Zero output impedance (i.e.,

, so that output voltage does not vary with output current).

, so that output voltage does not vary with output current). - Zero noise.

- Infinite Common-mode rejection ratio (CMRR).

- Infinite Power supply rejection ratio for both power supply rails.

These ideals can be summarized by the two "golden rules":

- I. The output attempts to do whatever is necessary to make the voltage difference between the inputs zero.

- II. The inputs draw no current.[4]:177

The first rule only applies in the usual case where the op-amp is used in a closed-loop design (negative feedback, where there is a signal path of some sort feeding back from the output to the inverting input). These rules are commonly used as a good first approximation for analyzing or designing op-amp circuits.[4]:177

In practice, none of these ideals can be perfectly realized, and various shortcomings and compromises have to be accepted. Depending on the parameters of interest, a real op-amp may be modeled to take account of some of the non-infinite or non-zero parameters using equivalent resistors and capacitors in the op-amp model. The designer can then include the effects of these undesirable, but real, effects into the overall performance of the final circuit. Some parameters may turn out to have negligible effect on the final design while others represent actual limitations of the final performance, that must be evaluated.

Real op-amps

Real op-amps differ from the ideal model in various respects.

DC imperfections

Real operational amplifiers suffer from several non-ideal effects:

- Finite gain

- Open-loop gain is infinite in the ideal operational amplifier but finite in real operational amplifiers. Typical devices exhibit open-loop DC gain ranging from 100,000 to over 1 million. So long as the loop gain (i.e., the product of open-loop and feedback gains) is very large, the circuit gain will be determined entirely by the amount of negative feedback (i.e., it will be independent of open-loop gain). In cases where closed-loop gain must be very high, the feedback gain will be very low, and the low feedback gain causes low loop gain; in these cases, the operational amplifier will cease to behave ideally.

- Finite input impedances

- The differential input impedance of the operational amplifier is defined as the impedance between its two inputs; the common-mode input impedance is the impedance from each input to ground. MOSFET-input operational amplifiers often have protection circuits that effectively short circuit any input differences greater than a small threshold, so the input impedance can appear to be very low in some tests. However, as long as these operational amplifiers are used in a typical high-gain negative feedback application, these protection circuits will be inactive. The input bias and leakage currents described below are a more important design parameter for typical operational amplifier applications.

- Non-zero output impedance

- Low output impedance is important for low-impedance loads; for these loads, the voltage drop across the output impedance of the amplifier will be significant. Hence, the output impedance of the amplifier limits the maximum power that can be provided. In configurations with a voltage-sensing negative feedback, the output impedance of the amplifier is effectively lowered; thus, in linear applications, op-amps usually exhibit a very low output impedance indeed. Negative feedback can not, however, reduce the limitations that Rload in conjunction with Rout place on the maximum and minimum possible output voltages; it can only reduce output errors within that range.

- Low-impedance outputs typically require high quiescent (i.e., idle) current in the output stage and will dissipate more power, so low-power designs may purposely sacrifice low output impedance.

- Input current

- Due to biasing requirements or leakage, a small amount of current (typically ~10 nanoamperes for bipolar op-amps, tens of picoamperes for JFET input stages, and only a few pA for MOSFET input stages) flows into the inputs. When large resistors or sources with high output impedances are used in the circuit, these small currents can produce large unmodeled voltage drops. If the input currents are matched, and the impedance looking out of both inputs are matched, then the voltages produced at each input will be equal. Because the operational amplifier operates on the difference between its inputs, these matched voltages will have no effect (unless the operational amplifier has poor CMRR, which is described below). It is more common for the input currents (or the impedances looking out of each input) to be slightly mismatched, and so a small offset voltage (different from the input offset voltage below) can be produced. This offset voltage can create offsets or drifting in the operational amplifier. It can often be nulled externally; however, many operational amplifiers include offset null or balance pins and some procedure for using them to remove this offset. Some operational amplifiers attempt to nullify this offset automatically.

- Input offset voltage

- This voltage, which is what is required across the op-amp's input terminals to drive the output voltage to zero,[5][nb 1] is related to the mismatches in input bias current. In the perfect amplifier, there would be no input offset voltage. However, it exists in actual op-amps because of imperfections in the differential amplifier that constitutes the input stage of the vast majority of these devices. Input offset voltage creates two problems: First, due to the amplifier's high voltage gain, it virtually assures that the amplifier output will go into saturation if it is operated without negative feedback, even when the input terminals are wired together. Second, in a closed loop, negative feedback configuration, the input offset voltage is amplified along with the signal and this may pose a problem if high precision DC amplification is required or if the input signal is very small.[nb 2]

- Common-mode gain

- A perfect operational amplifier amplifies only the voltage difference between its two inputs, completely rejecting all voltages that are common to both. However, the differential input stage of an operational amplifier is never perfect, leading to the amplification of these identical voltages to some degree. The standard measure of this defect is called the common-mode rejection ratio (denoted CMRR). Minimization of common mode gain is usually important in non-inverting amplifiers (described below) that operate at high amplification.

- Output sink current

- The output sink current is maximum current allowed to sink into the output stage. Some manufacturers show the output voltage vs. the output sink current plot, which gives an idea of the output voltage when it is sinking current from another source into the output pin.

- Temperature effects

- All parameters change with temperature. Temperature drift of the input offset voltage is especially important.

- Power-supply rejection

- The output of a perfect operational amplifier will be completely independent from ripples that arrive on its power supply inputs. Every real operational amplifier has a specified power supply rejection ratio (PSRR) that reflects how well the op-amp can reject changes in its supply voltage. Copious use of bypass capacitors can improve the PSRR of many devices, including the operational amplifier.

- Drift

- Real op-amp parameters are subject to slow change over time and with changes in temperature, input conditions, etc.

- Noise

- Amplifiers generate random voltage at the output even when there is no signal applied. This can be due to thermal noise and flicker noise of the devices. For applications with high gain or high bandwidth, noise becomes a very important consideration.

AC imperfections

The op-amp gain calculated at DC does not apply at higher frequencies. Thus, for high-speed operation, more sophisticated considerations must be used in an op-amp circuit design.

- Finite bandwidth

- All amplifiers have finite bandwidth. To a first approximation, the op-amp has the frequency response of an integrator with gain. That is, the gain of a typical op-amp is inversely proportional to frequency and is characterized by its gain–bandwidth product (GBWP). For example, an op-amp with a GBWP of 1 MHz would have a gain of 5 at 200 kHz, and a gain of 1 at 1 MHz. This dynamic response coupled with the very high DC gain of the op-amp gives it the characteristics of a first-order low-pass filter with very high DC gain and low cutoff frequency given by the GBWP divided by the DC gain.

- The finite bandwidth of an op-amp can be the source of several problems, including:

- Stability. Associated with the bandwidth limitation is a phase difference between the input signal and the amplifier output that can lead to oscillation in some feedback circuits. For example, a sinusoidal output signal meant to interfere destructively with an input signal of the same frequency will interfere constructively if delayed by 180 degrees. In these cases, the feedback circuit can be stabilized by means of frequency compensation, which increases the gain or phase margin of the open-loop circuit. The circuit designer can implement this compensation externally with a separate circuit component. Alternatively, the compensation can be implemented within the operational amplifier with the addition of a dominant pole that sufficiently attenuates the high-frequency gain of the operational amplifier. The location of this pole may be fixed internally by the manufacturer or configured by the circuit designer using methods specific to the op-amp. In general, dominant-pole frequency compensation reduces the bandwidth of the op-amp even further. When the desired closed-loop gain is high, op-amp frequency compensation is often not needed because the requisite open-loop gain is sufficiently low; consequently, applications with high closed-loop gain can make use of op-amps with higher bandwidths.

- Noise, Distortion, and Other Effects. Reduced bandwidth also results in lower amounts of feedback at higher frequencies, producing higher distortion, noise, and output impedance and also reduced output phase linearity as the frequency increases.

- Typical low-cost, general-purpose op-amps exhibit a GBWP of a few megahertz. Specialty and high-speed op-amps exist that can achieve a GBWP of hundreds of megahertz. For very high-frequency circuits, a current-feedback operational amplifier is often used.

- Input capacitance

- Most important for high frequency operation because it further reduces the open-loop bandwidth of the amplifier.

- Common-mode gain

- See DC imperfections, above.

Non-linear imperfections

- Saturation

- output voltage is limited to a minimum and maximum value close to the power supply voltages.[nb 3] Saturation occurs when the output of the amplifier reaches this value and is usually due to:

- In the case of an op-amp using a bipolar power supply, a voltage gain that produces an output that is more positive or more negative than that maximum or minimum; or

- In the case of an op-amp using a single supply voltage, either a voltage gain that produces an output that is more positive than that maximum, or a signal so close to ground that the amplifier's gain is not sufficient to raise it above the lower threshold.[nb 4]

- Slewing

- the amplifier's output voltage reaches its maximum rate of change. Measured as the slew rate, it is usually specified in volts per microsecond. When slewing occurs, further increases in the input signal have no effect on the rate of change of the output. Slewing is usually caused by internal capacitances in the amplifier, especially those used to implement its frequency compensation.

- Non-linear input-output relationship

- The output voltage may not be accurately proportional to the difference between the input voltages. It is commonly called distortion when the input signal is a waveform. This effect will be very small in a practical circuit if substantial negative feedback is used.

Power considerations

- Limited output current

- The output current must be finite. In practice, most op-amps are designed to limit the output current so as not to exceed a specified level – around 25 mA for a type 741 IC op-amp – thus protecting the op-amp and associated circuitry from damage. Modern designs are electronically more rugged than earlier implementations and some can sustain direct short circuits on their outputs without damage.

- Limited dissipated power

- The output current flows through the op-amp's internal output impedance, dissipating heat. If the op-amp dissipates too much power, then its temperature will increase above some safe limit. The op-amp may enter thermal shutdown, or it may be destroyed.

Modern integrated FET or MOSFET op-amps approximate more closely the ideal op-amp than bipolar ICs when it comes to input impedance and input bias and offset currents. Bipolars are generally better when it comes to input voltage offset, and often have lower noise. Generally, at room temperature, with a fairly large signal, and limited bandwidth, FET and MOSFET op-amps now offer better performance.

Internal circuitry of 741 type op-amp

Though designs vary between products and manufacturers, all op-amps have basically the same internal structure, which consists of three stages:

- Differential amplifier – provides low noise amplification, high input impedance, usually a differential output.

- Voltage amplifier – provides high voltage gain, a single-pole frequency roll-off, usually single-ended output.

- Output amplifier – provides high current driving capability, low output impedance, current limiting and short circuit protection circuitry.

IC op-amps as implemented in practice are moderately complex integrated circuits. A typical example is the ubiquitous 741 op-amp designed by Dave Fullagar in Fairchild Semiconductor after the remarkable Widlar LM301. Thus the basic architecture of the 741 is identical to that of the 301.[6]

Input stage

The input stage is a composed differential amplifier with a complex biasing circuit and a current mirror active load.

Differential amplifier

It is implemented by two cascaded stages satisfying the conflicting requirements. The first stage consists of the NPN-based input emitter followers Q1 and Q2 that provide high input impedance. The next is the PNP-based common base pair Q3 and Q4 that eliminates the undesired Miller effect, shifts the voltage level downwards and provides a sufficient voltage gain to drive the next class A amplifier. The PNP transistors also help to increase the reverse Vbe rating (the base-emitter junctions of the NPN transistors Q1 and Q2 break down at around 7 V but the PNP transistors Q3 and Q4 have breakdown voltages around 50 V).[7]

Biasing circuit

The classical emitter-coupled differential stage is biased from the side of the emitters by connecting a constant current source to them. The series negative feedback (the emitter degeneration) makes the transistors act as voltage stabilizers; it forces them to adjust their VBE voltages so that to pass the current through their collector-emitter junctions. As a result, the quiescent current is β-independent.

Here, the Q3/Q4 emitters are already used as inputs. Their collectors are separated and cannot be used as inputs for the quiescent current source since they behave as current sources. So, the quiescent current can be set only from the side of the bases by connecting a constant current source to them. To make it not depend on β as above, a negative but parallel feedback is used. For this purpose, the total quiescent current is mirrored by Q8-Q9 current mirror and the negative feedback is taken from the Q9 collector. Now it makes the transistors Q1-Q4 adjust their VBE voltages so that to pass the desired quiescent current. The effect is the same as at the classical emitter-coupled pair - the quiescent current is β-independent. It is interesting fact that "to the extent that all PNP βs match, this clever circuit generates just the right β-dependent base current to produce a β-independent collector current".[6] The biasing base currents are usually provided only by the negative power supply; they should come from the ground and enter the bases. But to ensure maximum high input impedances, the biasing loops are not internally closed between the base and ground; it is expected they will be closed externally by the input sources. So, the sources have to be galvanic (DC) to ensure paths for the biasing currents and low resistive enough (tens or hundreds kilohms) to not create significant voltage drops across them. Otherwise, additional DC elements should be connected between the bases and the ground (or the positive power supply).

The quiescent current is set by the 39 kΩ resistor that is common for the two current mirrors Q12-Q13 and Q10-Q11. The current determined by this resistor acts also as a reference for the other bias currents used in the chip. The Widlar current mirror built by Q10, Q11, and the 5 kΩ resistor produces a very small fraction of  at the Q10 collector. This small constant current through Q10's collector supplies the base currents for Q3 and Q4 as well as the Q9 collector current. The Q8/Q9 current mirror tries to make Q9 collector current the same as the Q3 and Q4 collector currents and succeeds with the help of the negative feedback. The Q9 collector voltage changes until the ratio between the Q3/Q4 base and collector currents becomes equal to β. Thus Q3 and Q4's combined base currents (which are of the same order as the overall chip's input currents) are a small fraction of the already small Q10 current.

at the Q10 collector. This small constant current through Q10's collector supplies the base currents for Q3 and Q4 as well as the Q9 collector current. The Q8/Q9 current mirror tries to make Q9 collector current the same as the Q3 and Q4 collector currents and succeeds with the help of the negative feedback. The Q9 collector voltage changes until the ratio between the Q3/Q4 base and collector currents becomes equal to β. Thus Q3 and Q4's combined base currents (which are of the same order as the overall chip's input currents) are a small fraction of the already small Q10 current.

Thus the quiescent current is set by Q10-Q11 current mirror without using a current-sensing negative feedback. The voltage-sensing negative feedback only helps this process by stabilizing Q9 collector (Q3/Q4 base) voltage.[nb 5] The feedback loop also isolates the rest of the circuit from common-mode signals by making the base voltage of Q3/Q4 follow tightly  below the higher of the two input voltages.

below the higher of the two input voltages.

Current mirror active load

The differential amplifier formed by Q1–Q4 drives an active load implemented as an improved current mirror (Q5–Q7) whose role is to convert the differential current input signal to a single ended voltage signal without the intrinsic 50% losses and to increase extremely the gain. This is achieved by copying the input signal from the left to the right side where the magnitudes of the two input signals add (Widlar used the same trick in μA702 and μA709). For this purpose, the input of the current mirror (Q5 collector) is connected to the left output (Q3 collector) and the output of the current mirror (Q6 collector) is connected to the right output of the differential amplifier (Q4 collector). Q7 increases the accuracy of the current mirror by decreasing the amount of signal current required from Q3 to drive the bases of Q5 and Q6.

Operation

Differential mode

The input voltage sources are connected through two "diode" strings, each of them consisting of two connected in series base-emitter junctions (Q1-Q3 and Q2-Q4), to the common point of Q3/Q4 bases. So, if the input voltages change slightly in opposite directions, Q3/Q4 bases stay at relatively constant voltage and the common base current does not change as well; it only vigorously steers between Q3/Q4 bases and makes the common quiescent current distribute between Q3/Q4 collectors in the same proportion.[nb 6] The current mirror inverts Q3 collector current and tries to pass it through Q4. In the middle point between Q4 and Q6, the signal currents (current changes) of Q3 and Q4 are subtracted. In this case (differential input signal), they are equal and opposite. Thus, the difference is twice the individual signal currents (ΔI - (-ΔI) = 2ΔI) and the differential to single ended conversion is completed without gain losses. The open circuit signal voltage appearing at this point is given by the product of the subtracted signal currents and the total circuit impedance (the paralleled collector resistances of Q4 and Q6). Since the collectors of Q4 and Q6 appear as high differential resistances to the signal current (Q4 and Q6 behave as current sources), the open circuit voltage gain of this stage is very high.[nb 7]

More intuitively, the transistor Q6 can be considered as a duplicate of Q3 and the combination of Q4 and Q6 can be thought as of a varying voltage divider composed of two voltage-controlled resistors. For differential input signals, they vigorously change their instant resistances in opposite directions but the total resistance stays constant (like a potentiometer with quickly moving slider). As a result, the current stays constant as well but the voltage at the middle point changes vigorously. As the two resistance changes are equal and opposite, the effective voltage change is twice the individual change.

The base current at the inputs is not zero and the effective differential input impedance of a 741 is about 2 MΩ. The "offset null" pins may be used to place external resistors in parallel with the two 1 kΩ resistors (typically in the form of the two ends of a potentiometer) to adjust the balancing of the Q5/Q6 current mirror and thus indirectly control the output of the op-amp when zero signal is applied between the inputs.

Common mode

If the input voltages change in the same direction, the negative feedback makes Q3/Q4 base voltage follow (with 2VBE below) the input voltage variations. Now the output part (Q10) of Q10-Q11 current mirror keeps up the common current through Q9/Q8 constant in spite of varying voltage. Q3/Q4 collector currents and accordingly, the output voltage in the middle point between Q4 and Q6, remain unchanged.

The following negative feedback (bootstrapping) increases virtually the effective op-amp common-mode input impedance.

Class A gain stage

The section outlined in magenta is the class A gain stage. The top-right current mirror Q12/Q13 supplies this stage by a constant current load, via the collector of Q13, that is largely independent of the output voltage. The stage consists of the two NPN transistors Q15/Q19 connected in a Darlington configuration and uses the output side of a current mirror as its collector (dynamic) load to achieve high gain. The transistor Q22 prevents this stage from saturating by diverting the excessive Q15 base current (it acts as a Baker clamp).

The 30 pF capacitor provides frequency selective negative feedback around the class A gain stage as a means of frequency compensation to stabilise the amplifier in feedback configurations. This technique is called Miller compensation and functions in a similar manner to an op-amp integrator circuit. It is also known as 'dominant pole compensation' because it introduces a dominant pole (one which masks the effects of other poles) into the open loop frequency response. This pole can be as low as 10 Hz in a 741 amplifier and it introduces a −3 dB loss into the open loop response at this frequency. This internal compensation is provided to achieve unconditional stability of the amplifier in negative feedback configurations where the feedback network is non-reactive and the closed loop gain is unity or higher. Hence, the use of the operational amplifier is simplified because no external compensation is required for unity gain stability; amplifiers without this internal compensation such as the 748 may require external compensation or closed-loop gains significantly higher than unity.

Output bias circuitry

The green outlined section (based on Q16) is a voltage level shifter named rubber diode, transistor Zener or VBE multiplier. In the circuit as shown, Q16 provides a constant voltage drop across its collector-emitter junction regardless of the current through it (it acts as a voltage stabilizer). This is achieved by introducing a negative feedback between Q16 collector and its base, i.e. by connecting a voltage divider with ratio β = 7.5 kΩ / (4.5 kΩ + 7.5 kΩ) = 0.625 composed by the two resistors. If the base current to the transistor is assumed to be zero, the negative feedback forces the transistor to increase its collector-emitter voltage up to 1 V until its base-emitter voltage reaches 0.625 V (a typical value for a BJT in the active region). This serves to bias the two output transistors slightly into conduction reducing crossover distortion (in some discrete component amplifiers, this function is usually achieved with a string of two silicon diodes).

The circuit can be presented as a negative feedback voltage amplifier with constant input voltage of 0.625 V and a feedback ratio of β = 0.625 (a gain of 1/β = 1.6). The same circuit but with β = 1 is used in the input current-setting part of the classical BJT current mirror.

Output stage

The output stage (outlined in cyan) is a Class AB push-pull emitter follower (Q14, Q20) amplifier with the bias set by the  multiplier voltage source Q16 and its base resistors. This stage is effectively driven by the collectors of Q13 and Q19. Variations in the bias with temperature, or between parts with the same type number, are common so crossover distortion and quiescent current may be subject to significant variation. The output range of the amplifier is about one volt less than the supply voltage, owing in part to

multiplier voltage source Q16 and its base resistors. This stage is effectively driven by the collectors of Q13 and Q19. Variations in the bias with temperature, or between parts with the same type number, are common so crossover distortion and quiescent current may be subject to significant variation. The output range of the amplifier is about one volt less than the supply voltage, owing in part to  of the output transistors Q14 and Q20.

of the output transistors Q14 and Q20.

The 25 Ω resistor in the output stage acts as a current sense to provide the output current-limiting function which limits the current in the emitter follower Q14 to about 25 mA for the 741. Current limiting for the negative output is done by sensing the voltage across Q19's emitter resistor and using this to reduce the drive into Q15's base. Later versions of this amplifier schematic may show a slightly different method of output current limiting. The output resistance is not zero, as it would be in an ideal op-amp, but with negative feedback it approaches zero at low frequencies.

Some considerations

Note: while the 741 was historically used in audio and other sensitive equipment, such use is now rare because of the improved noise performance of more modern op-amps. Apart from generating noticeable hiss, 741s and other older op-amps may have poor common-mode rejection ratios and so will often introduce cable-borne mains hum and other common-mode interference, such as switch 'clicks', into sensitive equipment.

The "741" has come to often mean a generic op-amp IC (such as μA741, LM301, 558, LM324, TBA221 - or a more modern replacement such as the TL071). The description of the 741 output stage is qualitatively similar for many other designs (that may have quite different input stages), except:

- Some devices (μA748, LM301, LM308) are not internally compensated (require an external capacitor from output to some point within the operational amplifier, if used in low closed-loop gain applications).

- Some modern devices have rail-to-rail output capability (output can be taken to positive or negative power supply rail within a few millivolts).

Classification

Op-amps may be classified by their construction:

- discrete (built from individual transistors or tubes/valves)

- IC (fabricated in an Integrated circuit) - most common

- hybrid

IC op-amps may be classified in many ways, including:

- Military, Industrial, or Commercial grade (for example: the LM301 is the commercial grade version of the LM101, the LM201 is the industrial version). This may define operating temperature ranges and other environmental or quality factors.

- Classification by package type may also affect environmental hardiness, as well as manufacturing options; DIP, and other through-hole packages are tending to be replaced by surface-mount devices.

- Classification by internal compensation: op-amps may suffer from high frequency instability in some negative feedback circuits unless a small compensation capacitor modifies the phase and frequency responses. Op-amps with a built-in capacitor are termed "compensated", or perhaps compensated for closed-loop gains down to (say) 5. All others are considered uncompensated.

- Single, dual and quad versions of many commercial op-amp IC are available, meaning 1, 2 or 4 operational amplifiers are included in the same package.

- Rail-to-rail input (and/or output) op-amps can work with input (and/or output) signals very close to the power supply rails.

- CMOS op-amps (such as the CA3140E) provide extremely high input resistances, higher than JFET-input op-amps, which are normally higher than bipolar-input op-amps.

- other varieties of op-amp include programmable op-amps (simply meaning the quiescent current, gain, bandwidth and so on can be adjusted slightly by an external resistor).

- manufacturers often tabulate their op-amps according to purpose, such as low-noise pre-amplifiers, wide bandwidth amplifiers, and so on.

Applications

Use in electronics system design

The use of op-amps as circuit blocks is much easier and clearer than specifying all their individual circuit elements (transistors, resistors, etc.), whether the amplifiers used are integrated or discrete. In the first approximation op-amps can be used as if they were ideal differential gain blocks; at a later stage limits can be placed on the acceptable range of parameters for each op-amp.

Circuit design follows the same lines for all electronic circuits. A specification is drawn up governing what the circuit is required to do, with allowable limits. For example, the gain may be required to be 100 times, with a tolerance of 5% but drift of less than 1% in a specified temperature range; the input impedance not less than one megohm; etc.

A basic circuit is designed, often with the help of circuit modeling (on a computer). Specific commercially available op-amps and other components are then chosen that meet the design criteria within the specified tolerances at acceptable cost. If not all criteria can be met, the specification may need to be modified.

A prototype is then built and tested; changes to meet or improve the specification, alter functionality, or reduce the cost, may be made.

Applications without using any feedback

That is, the op-amp is being used as a voltage comparator. Note that a device designed primarily as a comparator may be better if, for instance, speed is important or a wide range of input voltages may be found, since such devices can quickly recover from full on or full off ("saturated") states.

A voltage level detector can be obtained if a reference voltage Vref is applied to one of the op-amp's inputs. This means that the op-amp is set up as a comparator to detect a positive voltage. If the voltage to be sensed, Ei, is applied to op amp's (+) input, the result is a noninverting positive-level detector: when Ei is above Vref, VO equals +Vsat; when Ei is below Vref, VO equals -Vsat. If Ei is applied to the inverting input, the circuit is an inverting positive-level detector: When Ei is above Vref, VO equals -Vsat.

A zero voltage level detector (Ei = 0) can convert, for example, the output of a sine-wave from a function generator into a variable-frequency square wave. If Ei is a sine wave, triangular wave, or wave of any other shape that is symmetrical around zero, the zero-crossing detector's output will be square. Zero-crossing detection may also be useful in triggering TRIACs at the best time to reduce mains interference and current spikes.

Positive feedback applications

Another typical configuration of op-amps is with positive feedback, which takes a fraction of the output signal back to the non-inverting input. An important application of it is the comparator with hysteresis, the Schmitt trigger. Some circuits may use Positive feedback and Negative feedback around the same amplifier, for example Triangle wave oscillators and active filters.

Because of the wide slew-range and lack of positive feedback, the response of all the open-loop level detectors described above will be relatively slow. External overall positive feedback may be applied but (unlike internal positive feedback that may be applied within the latter stages of a purpose-designed comparator) this markedly affects the accuracy of the zero-crossing detection point. Using a general-purpose op-amp, for example, the frequency of Ei for the sine to square wave converter should probably be below 100 Hz.

Negative feedback applications

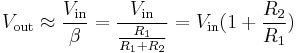

Non-inverting amplifier

In a non-inverting amplifier, the output voltage changes in the same direction as the input voltage.

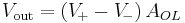

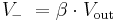

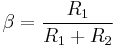

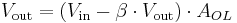

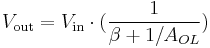

The gain equation for the op-amp is:

However, in this circuit  – is a function of

– is a function of  because of the negative feedback through the

because of the negative feedback through the  network.

network.  and

and  form a voltage divider, and as

form a voltage divider, and as  – is a high-impedance input, it does not load it appreciably. Consequently:

– is a high-impedance input, it does not load it appreciably. Consequently:

where

Substituting this into the gain equation, we obtain:

Solving for  :

:

If  is very large, this simplifies to

is very large, this simplifies to

.

.

Note that the non-inverting input of the operational amplifier will need a path for DC to ground; if the signal source might not give this, or if that source requires a given load impedance, the circuit will require another resistor - from input to ground. In either case, the ideal value for the feedback resistors (to give minimum offset voltage) will be such that the two resistances in parallel roughly equal the resistance to ground at the non-inverting input pin.

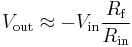

Inverting amplifier

In an inverting amplifier, the output voltage changes in an opposite direction to the input voltage.

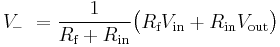

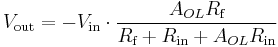

As with the non-inverting amplifier, we start with the gain equation of the op-amp:

This time,  – is a function of both

– is a function of both  and

and  due to the voltage divider formed by

due to the voltage divider formed by  and

and  . Again, the op-amp input does not apply an appreciable load, so:

. Again, the op-amp input does not apply an appreciable load, so:

Substituting this into the gain equation and solving for  :

:

If  is very large, this simplifies to

is very large, this simplifies to

.

.

A resistor is often inserted between the non-inverting input and ground (so both inputs "see" similar resistances), reducing the input offset voltage due to different voltage drops due to bias current, and may reduce distortion in some op-amps.

A DC-blocking capacitor may be inserted in series with the input resistor when a frequency response down to DC is not needed and any DC voltage on the input is unwanted. That is, the capacitive component of the input impedance inserts a DC zero and a low-frequency pole that gives the circuit a bandpass or high-pass characteristic.

The potentials at the operational amplifier inputs remain virtually constant (near ground) in the inverting configuration. The constant operating potential typically results in distortion levels that are lower than those attainable with the non-inverting topology.

Other applications

- audio- and video-frequency pre-amplifiers and buffers

- differential amplifiers

- differentiators and integrators

- filters

- precision rectifiers

- precision peak detectors

- voltage and current regulators

- analog calculators

- analog-to-digital converters

- digital-to-analog converters

- voltage clamps

- oscillators and waveform generators

Most single, dual and quad op-amps available have a standardized pin-out which permits one type to be substituted for another without wiring changes. A specific op-amp may be chosen for its open loop gain, bandwidth, noise performance, input impedance, power consumption, or a compromise between any of these factors.

Historical timeline

1941: A vacuum tube op-amp. An op-amp, defined as a general-purpose, DC-coupled, high gain, inverting feedback amplifier, is first found in U.S. Patent 2,401,779 "Summing Amplifier" filed by Karl D. Swartzel Jr. of Bell Labs in 1941. This design used three vacuum tubes to achieve a gain of 90 dB and operated on voltage rails of ±350 V. It had a single inverting input rather than differential inverting and non-inverting inputs, as are common in today's op-amps. Throughout World War II, Swartzel's design proved its value by being liberally used in the M9 artillery director designed at Bell Labs. This artillery director worked with the SCR584 radar system to achieve extraordinary hit rates (near 90%) that would not have been possible otherwise.[8]

1947: An op-amp with an explicit non-inverting input. In 1947, the operational amplifier was first formally defined and named in a paper by Professor John R. Ragazzini of Columbia University. In this same paper a footnote mentioned an op-amp design by a student that would turn out to be quite significant. This op-amp, designed by Loebe Julie, was superior in a variety of ways. It had two major innovations. Its input stage used a long-tailed triode pair with loads matched to reduce drift in the output and, far more importantly, it was the first op-amp design to have two inputs (one inverting, the other non-inverting). The differential input made a whole range of new functionality possible, but it would not be used for a long time due to the rise of the chopper-stabilized amplifier.[9]

1949: A chopper-stabilized op-amp. In 1949, Edwin A. Goldberg designed a chopper-stabilized op-amp.[10] This set-up uses a normal op-amp with an additional AC amplifier that goes alongside the op-amp. The chopper gets an AC signal from DC by switching between the DC voltage and ground at a fast rate (60 Hz or 400 Hz). This signal is then amplified, rectified, filtered and fed into the op-amp's non-inverting input. This vastly improved the gain of the op-amp while significantly reducing the output drift and DC offset. Unfortunately, any design that used a chopper couldn't use their non-inverting input for any other purpose. Nevertheless, the much improved characteristics of the chopper-stabilized op-amp made it the dominant way to use op-amps. Techniques that used the non-inverting input regularly would not be very popular until the 1960s when op-amp ICs started to show up in the field.

In 1953, vacuum tube op-amps became commercially available with the release of the model K2-W from George A. Philbrick Researches, Incorporated. The designation on the devices shown, GAP/R, is an acronym for the complete company name. Two nine-pin 12AX7 vacuum tubes were mounted in an octal package and had a model K2-P chopper add-on available that would effectively "use up" the non-inverting input. This op-amp was based on a descendant of Loebe Julie's 1947 design and, along with its successors, would start the widespread use of op-amps in industry.

1961: A discrete IC op-amps. With the birth of the transistor in 1947, and the silicon transistor in 1954, the concept of ICs became a reality. The introduction of the planar process in 1959 made transistors and ICs stable enough to be commercially useful. By 1961, solid-state, discrete op-amps were being produced. These op-amps were effectively small circuit boards with packages such as edge connectors. They usually had hand-selected resistors in order to improve things such as voltage offset and drift. The P45 (1961) had a gain of 94 dB and ran on ±15 V rails. It was intended to deal with signals in the range of ±10 V.

1961: A varactor bridge op-amps. There have been many different directions taken in op-amp design. Varactor bridge op-amps started to be produced in the early 1960s.[11][12] They were designed to have extremely small input current and are still amongst the best op-amps available in terms of common-mode rejection with the ability to correctly deal with hundreds of volts at their inputs.

1962: An op-amps in potted modules. By 1962, several companies were producing modular potted packages that could be plugged into printed circuit boards. These packages were crucially important as they made the operational amplifier into a single black box which could be easily treated as a component in a larger circuit.

1963: A monolithic IC op-amp. In 1963, the first monolithic IC op-amp, the μA702 designed by Bob Widlar at Fairchild Semiconductor, was released. Monolithic ICs consist of a single chip as opposed to a chip and discrete parts (a discrete IC) or multiple chips bonded and connected on a circuit board (a hybrid IC). Almost all modern op-amps are monolithic ICs; however, this first IC did not meet with much success. Issues such as an uneven supply voltage, low gain and a small dynamic range held off the dominance of monolithic op-amps until 1965 when the μA709[13] (also designed by Bob Widlar) was released.

1968: Release of the μA741. The popularity of monolithic op-amps was further improved upon the release of the LM101 in 1967, which solved a variety of issues, and the subsequent release of the μA741 in 1968. The μA741 was extremely similar to the LM101 except that Fairchild's facilities allowed them to include a 30 pF compensation capacitor inside the chip instead of requiring external compensation. This simple difference has made the 741 the canonical op-amp and many modern amps base their pinout on the 741s. The μA741 is still in production, and has become ubiquitous in electronics—many manufacturers produce a version of this classic chip, recognizable by part numbers containing 741. The same part is manufactured by several companies.

1970: First high-speed, low-input current FET design. In the 1970s high speed, low-input current designs started to be made by using FETs. These would be largely replaced by op-amps made with MOSFETs in the 1980s. During the 1970s single sided supply op-amps also became available.

1972: Single sided supply op-amps being produced. A single sided supply op-amp is one where the input and output voltages can be as low as the negative power supply voltage instead of needing to be at least two volts above it. The result is that it can operate in many applications with the negative supply pin on the op-amp being connected to the signal ground, thus eliminating the need for a separate negative power supply.

The LM324 (released in 1972) was one such op-amp that came in a quad package (four separate op-amps in one package) and became an industry standard. In addition to packaging multiple op-amps in a single package, the 1970s also saw the birth of op-amps in hybrid packages. These op-amps were generally improved versions of existing monolithic op-amps. As the properties of monolithic op-amps improved, the more complex hybrid ICs were quickly relegated to systems that are required to have extremely long service lives or other specialty systems.

Recent trends. Recently supply voltages in analog circuits have decreased (as they have in digital logic) and low-voltage op-amps have been introduced reflecting this. Supplies of ±5 V and increasingly 3.3 V (sometimes as low as 1.8 V) are common. To maximize the signal range modern op-amps commonly have rail-to-rail output (the output signal can range from the lowest supply voltage to the highest) and sometimes rail-to-rail inputs.

See also

- Operational amplifier applications

- Differential amplifier

- Instrumentation amplifier

- Active filter

- Current-feedback operational amplifier

- Operational transconductance amplifier

- George A. Philbrick

- Bob Widlar

- Analog computer

- Negative feedback amplifier

Notes

- ^ This definition hews to the convention of measuring op-amp parameters with respect to the zero voltage point in the circuit, which is usually half the total voltage between the amplifier's positive and negative power rails.

- ^ Many older designs of operational amplifiers have offset null inputs to allow the offset to be manually adjusted away. Modern precision op-amps can have internal circuits that automatically cancel this offset using choppers or other circuits that measure the offset voltage periodically and subtract it from the input voltage.

- ^ That the output cannot reach the power supply voltages is usually the result of limitations of the amplifier's output stage transistors. See Output stage.

- ^ The output of older op-amps can reach to within one or two volts of the supply rails. The output of newer so-called "rail to rail" op-amps can reach to within millivolts of the supply rails when providing low output currents.

- ^ This arrangement can be generalized by an equivalent circuit consisting of a constant current source loaded by a voltage source; the voltage source fixes the voltage across the current source while the current source sets the current through the voltage source. As the two heterogeneous sources provide ideal load conditions for each other, this circuit solution is widely used in cascode circuits, Wilson current mirror, the input part of the simple current mirror, emitter-coupled and other exotic circuits.

- ^ If the input differential voltage changes significantly (with more than about a hundred millivolts), the base-emitter junctions of the transistors driven by the lower input voltage (e.g., Q1 and Q3) become backward biased and the total common base current flows through the other (Q2 and Q4) base-emitter junctions. However, the high breakdown voltage of the PNP transistors Q3/Q4 prevents Q1/Q2 base-emitter junctions from damaging when the input difference voltage increases up to 50 V because of the unlimited current that may flow directly through the "diode bridge" between the two input sources.

- ^ This circuit (and geometrical) phenomenon can be illustrated graphically by superimposing the Q4 and Q6 output characteristics (almost parallel horizontal lines) on the same coordinate system. When the input voltages vary slightly in opposite directions, the two curves move slightly toward each other in the vertical direction but the operating (cross) point moves vigorously in the horizontal direction. The ratio between the two movements represents the high amplification.

References

- ^ MAXIM Application Note 1108: Understanding Single-Ended, Pseudo-Differential and Fully-Differential ADC Inputs – Retrieved November 10, 2007

- ^ Analog devices MT-044 TUTORIAL

- ^ Jacob Millman, Microelectronics: Digital and Analog Circuits and Systems, McGraw-Hill, 1979, ISBN 0-07-042327-x, pp. 523-527

- ^ a b Horowitz, Paul; Hill, Winfield (1989). The Art of Electronics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521370957. http://books.google.com/books?id=bkOMDgwFA28C&pg=PA177&lpg=PA177#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- ^ D.F. Stout Handbook of Operational Amplifier Circuit Design (McGraw-Hill, 1976, ISBN 007061797X ) pp. 1–11.

- ^ a b Lee, Thomas H. (November 18, 2002), IC Op-Amps Through the Ages, Stanford University, http://www.stanford.edu/class/archive/ee/ee214/ee214.1032/Handouts/ho18opamp.pdf; Handout #18: EE214 Fall 2002

- ^ The uA741 Operational Amplifier

- ^ Jung, Walter G. (2004). "Chapter 8: Op Amp History". Op Amp Applications Handbook. Newnes. p. 777. ISBN 9780750678445. http://books.google.com/books?id=dunqt1rt4sAC. Retrieved 2008-11-15.

- ^ Jung, Walter G. (2004). "Chapter 8: Op Amp History". Op Amp Applications Handbook. Newnes. p. 779. ISBN 9780750678445. http://books.google.com/books?id=dunqt1rt4sAC. Retrieved 2008-11-15.

- ^ http://www.analog.com/library/analogDialogue/archives/39-05/Web_ChH_final.pdf

- ^ http://www.philbrickarchive.org/

- ^ June 1961 advertisement for Philbrick P2, http://www.philbrickarchive.org/p2%20and%206033%20ad%20rsi%20vol32%20no6%20june1961.pdf

- ^ A.P. Malvino, Electronic Principles (2nd Ed. 1979. ISBN 0-07-039867-4) p. 476.

Further reading

- Basic Operational Amplifiers and Linear Integrated Circuits; 2nd Ed; Thomas L Floyd; 593 pages; 1998; ISBN 978-0130829870.

- Design with Operational Amplifiers and Analog Integrated Circuits; 3rd Ed; Sergio Franco; 672 pages; 2001; ISBN 978-0072320848.

- Operational Amplifiers and Linear Integrated Circuits; 6th Ed; Robert F Coughlin; 529 pages; 2000; ISBN 978-0130149916.

- Op-Amps and Linear Integrated Circuits; 4th Ed; Ram Gayakwad; 543 pages; 1999; ISBN 978-0132808682.

External links

- Simple Op Amp Measurements How to measure offset voltage, offset and bias current, gain, CMRR, and PSRR.

- Introduction to op-amp circuit stages, second order filters, single op-amp bandpass filters, and a simple intercom

- Hyperphysics – descriptions of common applications

- Single supply op-amp circuit collection

- Op-amp circuit collection

- Opamps for everyone Downloadable book.

- MOS op amp design: A tutorial overview

- High Speed OpAmp Techniques very practical and readable – with photos and real waveforms

- Op Amp Applications Downloadable book. Can also be bought

- Operational Amplifier Noise Prediction (All Op Amps) using spot noise

- Operational Amplifier Basics

- History of the Op-amp from vacuum tubes to about 2002. Lots of detail, with schematics. IC part is somewhat ADI-centric.

- ECE 209: Operational amplifier basics – Brief document explaining zero error by naive high-gain negative feedback. Gives single OpAmp example that generalizes typical configurations.

- Loebe Julie historical OpAmp interview by Bob Pease

- www.PhilbrickArchive.org – A free repository of materials from George A Philbrick / Researches - Operational Amplifier Pioneer