Fraction (mathematics)

A fraction (from Latin: fractus, "broken") represents a part of a whole or, more generally, any number of equal parts. When spoken in everyday English, we specify how many parts of a certain size there are, for example, one-half, five-eighths and three-quarters.

A common or vulgar fraction, such as 1/2, 8/5, 3/4, etc., consists of an integer numerator and a non-zero integer denominatorâthe numerator representing a number of equal parts and the denominator indicating how many of those parts make up a whole. An example is 3/4, in which the numerator, 3, tells us that the fraction represents 3 equal parts, and the denominator, 4, tells us that 4 parts equal a whole. The picture to the right illustrates 3/4 of a cake.

Fractional numbers can also be written without using explicit numerators or denominators, by using decimals, percent signs, or negative exponents (as in 0.01, 1%, and 10â2 respectively, all of which are equivalent to 1/100). An integer (e.g. the number 7) has an implied denominator of one, meaning that the number can be expressed as a fraction like 7/1.

Other uses for fractions are to represent ratios and to represent division. Thus the fraction 3/4 is also used to represent the ratio 3:4 (the ratio of the part to the whole) and the division 3 ÷ 4 (three divided by four).

In mathematics the set of all numbers which can be expressed in the form a/b, where a and b are integers and b is not zero, is called the set of rational numbers and is represented by the symbol Q, which stands for quotient. The test for a number being a rational number is that it can be written in that form (i.e., as a common fraction). However, the word fraction is also used to describe mathematical expressions that are not rational numbers, for example algebraic fractions (quotients of algebraic expressions), and expressions that contain irrational numbers, such as â2/2 (see square root of 2) and Ï/4 (see proof that Ï is irrational).

Forms of fractions

Common, vulgar, or simple fractions

A common fraction (also known as a vulgar fraction or simple fraction) is a rational number written as a/b or  , where the integers a and b are called the numerator and the denominator, respectively.[1] The numerator represents a number of equal parts and the denominator, which cannot be zero, indicates how many of those parts make up a unit or a whole. In the examples 2/5 and 7/3, the slanting line is called a solidus or forward slash. In the examples

, where the integers a and b are called the numerator and the denominator, respectively.[1] The numerator represents a number of equal parts and the denominator, which cannot be zero, indicates how many of those parts make up a unit or a whole. In the examples 2/5 and 7/3, the slanting line is called a solidus or forward slash. In the examples  and

and  , the horizontal line is called a vinculum or, informally, a "fraction bar".

, the horizontal line is called a vinculum or, informally, a "fraction bar".

Writing simple fractions

In computer displays and typography, simple fractions are sometimes printed as a single character, e.g. ½ (one half).

Scientific publishing distinguishes four ways to set fractions, together with guidelines on use:[2]

- case fractions:

, generally used for simple fractions and for showing mathematical operations;

, generally used for simple fractions and for showing mathematical operations; - special fractions: ½, not used in modern mathematical notation, but in other contexts;

- shilling fractions: 1/2, so called because this notation was used for pre-decimal British currency (£sd), as in 2/6 for a half crown, meaning two shillings and six pence. While the notation "two shillings and six pence" did not represent a fraction, the forward slash is now used in fractions, especially for fractions inline with prose (rather than displayed), to avoid uneven lines. It is also used for fractions within fractions (complex fractions) or within exponents to increase legibility;

- built-up fractions:

, while large and legible, these can be disruptive, particularly for simple fractions or within complex fractions.

, while large and legible, these can be disruptive, particularly for simple fractions or within complex fractions.

Proper and improper common fractions

Common fractions can be classified as either proper or improper. When the numerator and the denominator are both positive, the fraction is called proper if the numerator is less than the denominator, and improper otherwise.[3][4] In general, a common fraction is said to be a proper fraction if the absolute value of the fraction is strictly less than oneâthat is, if the fraction is between -1 and 1 (but not equal to -1 or 1).[5][6] It is said to be an improper fraction (U.S., British or Australian) or top-heavy fraction (British, occasionally North America) if the absolute value of the fraction is greater than or equal to 1. Examples of proper fractions are 2/3, -3/4, and 4/9; examples of improper fractions are 9/4, -4/3, and 8/3.

Mixed numbers

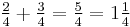

A mixed numeral (often called a mixed number, also called a mixed fraction) is the sum of a non-zero integer and a proper fraction. This sum is implied without the use of any visible operator such as "+". For example, in referring to two entire cakes and three quarters of another cake, the whole and fractional parts of the number are written next to each other:  .

.

This is not to be confused with the algebra rule of implied multiplication. When two algebraic expressions are written next to each other, the operation of multiplication is said to be "understood". In algebra,  for example is not a mixed number. Instead, multiplication is understood:

for example is not a mixed number. Instead, multiplication is understood:  .

.

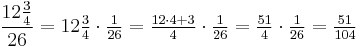

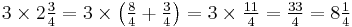

An improper fraction is another way to write a whole plus a part. A mixed number can be converted to an improper fraction as follows:

- Write the mixed number

as a sum

as a sum  .

. - Convert the whole number to an improper fraction with the same denominator as the fractional part,

.

. - Add the fractions. The resulting sum is the improper fraction. In the example,

.

.

Similarly, an improper fraction can be converted to a mixed number as follows:

- Divide the numerator by the denominator. In the example,

, divide 11 by 4. 11 ÷ 4 = 2 with remainder 3.

, divide 11 by 4. 11 ÷ 4 = 2 with remainder 3. - The quotient (without the remainder) becomes the whole number part of the mixed number. The remainder becomes the numerator of the fractional part. In the example, 2 is the whole number part and 3 is the numerator of the fractional part.

- The new denominator is the same as the denominator of the improper fraction. In the example, they are both 4. Thus

.

.

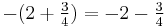

Mixed numbers can also be negative, as in  , which equals

, which equals  .

.

Reciprocals and the "invisible denominator"

The reciprocal of a fraction is another fraction with the numerator and denominator reversed. The reciprocal of  , for instance, is

, for instance, is  . The product of a fraction and its reciprocal is 1, hence the reciprocal is the multiplicative inverse of a fraction. Any integer can be written as a fraction with the number one as denominator. For example, 17 can be written as

. The product of a fraction and its reciprocal is 1, hence the reciprocal is the multiplicative inverse of a fraction. Any integer can be written as a fraction with the number one as denominator. For example, 17 can be written as  , where 1 is sometimes referred to as the invisible denominator. Therefore, every fraction or integer except for zero has a reciprocal. The reciprocal of 17 is

, where 1 is sometimes referred to as the invisible denominator. Therefore, every fraction or integer except for zero has a reciprocal. The reciprocal of 17 is  .

.

Complex fractions

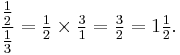

In a complex fraction, either the numerator, or the denominator, or both, is a fraction or a mixed number[7][8], corresponding to division of fractions. For example,  and

and  are complex fractions. To reduce a complex fraction to a simple fraction, treat the longest fraction line as representing division. For example:

are complex fractions. To reduce a complex fraction to a simple fraction, treat the longest fraction line as representing division. For example:

If, in a complex fraction, there is no clear way to tell which fraction line takes precedence, then the expression is improperly formed, and meaningless.

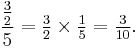

Compound fractions

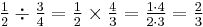

A compound fraction is a fraction of a fraction, or any number of fractions connected with the word of[7][8], corresponding to multiplication of fractions. To reduce a compound fraction to a simple fraction, just carry out the multiplication (see the section on multiplication). For example,  of

of  is a compound fraction, corresponding to

is a compound fraction, corresponding to  . The terms compound fraction and complex fraction are closely related and sometimes one is used as a synonym for the other.

. The terms compound fraction and complex fraction are closely related and sometimes one is used as a synonym for the other.

Decimal fractions and percentages

A decimal fraction is a fraction whose denominator is not given explicitly, but is understood to be an integer power of ten. Decimal fractions are commonly expressed using decimal notation in which the implied denominator is determined by the number of digits to the right of a decimal separator, the appearance of which (e.g., a period, a raised period (â¢), a comma) depends on the locale (for examples, see decimal separator). Thus for 0.75 the numerator is 75 and the implied denominator is 10 to the second power, viz. 100, because there are two digits to the right of the decimal separator. In decimal numbers greater than 1 (such as 3.75), the fractional part of the number is expressed by the digits to the right of the decimal (with a value of 0.75 in this case). 3.75 can be written either as an improper fraction, 375/100, or as a mixed number,  .

.

Decimal fractions can also be expressed using scientific notation with negative exponents, such as 6.023Ã10â7, which represents 0.0000006023. The 10â7 represents a denominator of 107. Dividing by 107 moves the decimal point 7 places to the left.

Decimal fractions with infinitely many digits to the right of the decimal separator represent an infinite series. For example, 1/3 = 0.333... represents the infinite series 3/10 + 3/100 + 3/1000 + ... .

Another kind of fraction is the percentage (Latin per centum meaning "per hundred", represented by the symbol %), in which the implied denominator is always 100. Thus, 75% means 75/100. Related concepts are the permille, with 1000 as implied denominator, and the more general parts-per notation, as in 75 parts per million, meaning that the proportion is 75/1,000,000.

Whether common fractions or decimal fractions are used is often a matter of taste and context. Common fractions are used most often when the denominator is relatively small. By mental calculation, it is easier to multiply 16 by 3/16 than to do the same calculation using the fraction's decimal equivalent (0.1875). And it is more accurate to multiply 15 by 1/3, for example, than it is to multiply 15 by any decimal approximation of one third. Monetary values are commonly expressed as decimal fractions, for example $3.75. However, as noted above, in pre-decimal British currency, shillings and pence were often given the form (but not the meaning) of a fraction, as, for example 3/6 (read "three and six") meaning 3 shillings and 6 pence, and having no relationship to the fraction 3/6.

Special cases

- A unit fraction is a vulgar fraction with a numerator of 1, e.g.

. Unit fractions can also be expressed using negative exponents, as in 2â1 which represents 1/2, and 2â2 which represents 1/(22) or 1/4.

. Unit fractions can also be expressed using negative exponents, as in 2â1 which represents 1/2, and 2â2 which represents 1/(22) or 1/4.

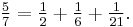

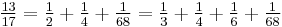

- An Egyptian fraction is the sum of distinct unit fractions of positive integers, e.g.

. This term derives from the fact that the ancient Egyptians expressed all fractions except

. This term derives from the fact that the ancient Egyptians expressed all fractions except  ,

,  and

and  in this manner. Every positive rational number can be expanded as an Egyptian fraction, such as

in this manner. Every positive rational number can be expanded as an Egyptian fraction, such as  For any positive rational number, there are infinitely many different such representations. For example,

For any positive rational number, there are infinitely many different such representations. For example,  .

.

- A dyadic fraction is a vulgar fraction in which the denominator is a power of two, e.g.

.

.

Arithmetic with fractions

Like whole numbers, fractions obey the commutative, associative, and distributive laws, and the rule against division by zero.

Equivalent fractions

Multiplying the numerator and denominator of a fraction by the same (non-zero) number results in a fraction that is equivalent to the original fraction. This is true because for any non-zero number  , the fraction

, the fraction  . Therefore, multiplying by

. Therefore, multiplying by  is equivalent to multiplying by one, and any number multiplied by one has the same value as the original number. By way of an example, start with the fraction

is equivalent to multiplying by one, and any number multiplied by one has the same value as the original number. By way of an example, start with the fraction  . When the numerator and denominator are both multiplied by 2, the result is

. When the numerator and denominator are both multiplied by 2, the result is  , which has the same value (0.5) as

, which has the same value (0.5) as  . To picture this visually, imagine cutting a cake into four pieces; two of the pieces together (

. To picture this visually, imagine cutting a cake into four pieces; two of the pieces together ( ) make up half the cake (

) make up half the cake ( ).

).

Dividing the numerator and denominator of a fraction by the same non-zero number will also yield an equivalent fraction. This is called reducing or simplifying the fraction. A simple fraction in which the numerator and denominator are coprime [that is, the only positive integer that goes into both the numerator and denominator evenly is 1) is said to be irreducible, in lowest terms, or in simplest terms. For example,  is not in lowest terms because both 3 and 9 can be exactly divided by 3. In contrast,

is not in lowest terms because both 3 and 9 can be exactly divided by 3. In contrast,  is in lowest termsâthe only positive integer that goes into both 3 and 8 evenly is 1.

is in lowest termsâthe only positive integer that goes into both 3 and 8 evenly is 1.

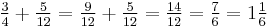

Using these rules, we can show that  =

=  =

=  =

=  .

.

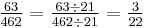

A common fraction can be reduced to lowest terms by dividing both the numerator and denominator by their greatest common divisor. For example, as the greatest common divisor of 63 and 462 is 21, the fraction  can be reduced to lowest terms by dividing the numerator and denominator by 21:

can be reduced to lowest terms by dividing the numerator and denominator by 21:

The Euclidean algorithm gives a method for finding the greatest common divisor of any two positive integers.

Comparing fractions

Comparing fractions with the same denominator only requires comparing the numerators.

because 3>2.

because 3>2.

If two positive fractions have the same numerator, then the fraction with the smaller denominator is the larger number. When a whole is divided into equal pieces, if fewer equal pieces are needed to make up the whole, then each piece must be larger. When two positive fractions have the same numerator, they represent the same number of parts, but in the fraction with the smaller denominator, the parts are larger.

One way to compare fractions with different numerators and denominators is to find a common denominator. To compare  and

and  , these are converted to

, these are converted to  and

and  . Then bd is a common denominator and the numerators ad and bc can be compared.

. Then bd is a common denominator and the numerators ad and bc can be compared.

?

?  gives

gives

It is not necessary to determine the value of the common denominator to compare fractions. This short cut is known as "cross multiplying" â you can just compare ad and bc, without computing the denominator.

?

?

Multiply top and bottom of each fraction by the denominator of the other fraction, to get a common denominator:

?

?

The denominators are now the same, but it is not necessary to calculate their value â only the numerators need to be compared. Since 5Ã17 (= 85) is greater than 4Ã18 (= 72),  .

.

Also note that every negative number, including negative fractions, is less than zero, and every positive number, including positive fractions, is greater than zero, so every negative fraction is less than any positive fraction.

Addition

The first rule of addition is that only like quantities can be added; for example, various quantities of quarters. Unlike quantities, such as adding thirds to quarters, must first be converted to like quantities as described below: Imagine a pocket containing two quarters, and another pocket containing three quarters; in total, there are five quarters. Since four quarters is equivalent to one (dollar), this can be represented as follows:

.

.

Adding unlike quantities

To add fractions containing unlike quantities (e.g. quarters and thirds), it is necessary to convert all amounts to like quantities. It is easy to work out the chosen type of fraction to convert to; simply multiply together the two denominators (bottom number) of each fraction.

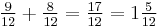

For adding quarters to thirds, both types of fraction are converted to  (twelfths).

(twelfths).

Consider adding the following two quantities:

First, convert  into twelfths by multiplying both the numerator and denominator by three:

into twelfths by multiplying both the numerator and denominator by three:  . Note that

. Note that  is equivalent to 1, which shows that

is equivalent to 1, which shows that  is equivalent to the resulting

is equivalent to the resulting  .

.

Secondly, convert  into twelfths by multiplying both the numerator and denominator by four:

into twelfths by multiplying both the numerator and denominator by four:  . Note that

. Note that  is equivalent to 1, which shows that

is equivalent to 1, which shows that  is equivalent to the resulting

is equivalent to the resulting  .

.

Now it can be seen that:

is equivalent to:

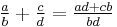

This method can be expressed algebraically:

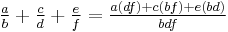

And for expressions consisting of the addition of three fractions:

This method always works, but sometimes there is a smaller denominator that can be used (a least common denominator). For example, to add  and

and  the denominator 48 can be used (the product of 4 and 12), but the smaller denominator 12 may also be used, being the least common multiple of 4 and 12.

the denominator 48 can be used (the product of 4 and 12), but the smaller denominator 12 may also be used, being the least common multiple of 4 and 12.

Subtraction

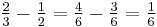

The process for subtracting fractions is, in essence, the same as that of adding them: find a common denominator, and change each fraction to an equivalent fraction with the chosen common denominator. The resulting fraction will have that denominator, and its numerator will be the result of subtracting the numerators of the original fractions. For instance,

Multiplication

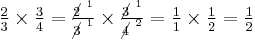

Multiplying a fraction by another fraction

To multiply fractions, multiply the numerators and multiply the denominators. Thus:

Why does this work? First, consider one third of one quarter. Using the example of a cake, if three small slices of equal size make up a quarter, and four quarters make up a whole, twelve of these small, equal slices make up a whole. Therefore a third of a quarter is a twelfth. Now consider the numerators. The first fraction, two thirds, is twice as large as one third. Since one third of a quarter is one twelfth, two thirds of a quarter is two twelfth. The second fraction, three quarters, is three times as large as one quarter, so two thirds of three quarters is three times as large as two thirds of one quarter. Thus two thirds times three quarters is six twelfths.

A short cut for multiplying fractions is called "cancellation". In effect, we reduce the answer to lowest terms during multiplication. For example:

A two is a common factor in both the numerator of the left fraction and the denominator of the right and is divided out of both. Three is a common factor of the left denominator and right numerator and is divided out of both.

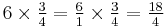

Multiplying a fraction by a whole number

Place the whole number over one and multiply.

This method works because the fraction 6/1 means six equal parts, each one of which is a whole.

Mixed numbers

When multiplying mixed numbers, it's best to convert the mixed number into an improper fraction. For example:

In other words,  is the same as

is the same as  , making 11 quarters in total (because 2 cakes, each split into quarters makes 8 quarters total) and 33 quarters is

, making 11 quarters in total (because 2 cakes, each split into quarters makes 8 quarters total) and 33 quarters is  , since 8 cakes, each made of quarters, is 32 quarters in total.

, since 8 cakes, each made of quarters, is 32 quarters in total.

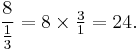

Division

To divide a fraction by a whole number, you may either divide the numerator by the number, if it goes evenly into the numerator, or multiply the denominator by the number. For example,  equals

equals  and also equals

and also equals  , which reduces to

, which reduces to  . To divide by a fraction, multiply by the reciprocal of that fraction. Thus,

. To divide by a fraction, multiply by the reciprocal of that fraction. Thus,  .

.

Converting between decimals and fractions

To change a common fraction to a decimal, divide the denominator into the numerator. Round the answer to the desired accuracy. For example, to change 1/4 to a decimal, divide 4 into 1.00, to obtain 0.25. To change 1/3 to a decimal, divide 3 into 1.0000..., and stop when the desired accuracy is obtained. Note that 1/4 can be written exactly with two decimal digits, while 1/3 cannot be written exactly with any finite number of decimal digits.

To change a decimal to a fraction, write in the denominator a 1 followed by as many zeroes as there are digits to the right of the decimal point, and write in the numerator all the digits in the original decimal, omitting the decimal point. Thus 12.3456 = 123456/10000.

Converting repeating decimals to fractions

Decimal numbers, while arguably more useful to work with when performing calculations, sometimes lack the precision that common fractions have. Sometimes an infinite number of repeating decimals is required to convey the same kind of precision. Thus, it is often useful to convert repeating decimals into fractions.

The preferred way to indicate a repeating decimal is to place a bar over the digits that repeat, for example 0.789 = 0.789789789⦠For repeating patterns where the repeating pattern begins immediately after the decimal point, a simple division of the pattern by the same number of nines as numbers it has will suffice. For example:

- 0.5 = 5/9

- 0.62 = 62/99

- 0.264 = 264/999

- 0.6291 = 6291/9999

In case leading zeros precede the pattern, the nines are suffixed by the same number of trailing zeros:

- 0.05 = 5/90

- 0.000392 = 392/999000

- 0.0012 = 12/9900

In case a non-repeating set of decimals precede the pattern (such as 0.1523987), we can write it as the sum of the non-repeating and repeating parts, respectively:

- 0.1523 + 0.0000987

Then, convert the repeating part to a fraction:

- 0.1523 + 987/9990000

Fractions in abstract mathematics

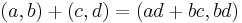

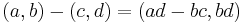

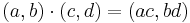

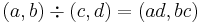

In addition to being of great practical importance, fractions are also studied by mathematicians, who check that the rules for fractions given above are consistent and reliable. Mathematicians define a fraction as an ordered pair (a, b) of integers a and b â 0, for which the operations addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division are defined as follows:[9]

(when c â 0)

(when c â 0)

In addition, an equivalence relation is specified as follows:  ~

~  if and only if

if and only if  .

.

These definitions agree in every case with the definitions given above; only the notation is different.

More generally, a and b may be elements of any integral domain R, in which case a fraction is an element of the field of fractions of R. For example, when a and b are polynomials in one indeterminate, the field of fractions is the field of rational fractions (also known as the field of rational functions). When a and b are integers, the field of fractions is the field of rational numbers.

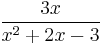

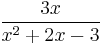

Algebraic fractions

An algebraic fraction is the indicated quotient of two algebraic expressions. Two examples of algebraic fractions are  and

and  . Algebraic fractions are subject to the same laws as arithmetic fractions.

. Algebraic fractions are subject to the same laws as arithmetic fractions.

If the numerator and the denominator are polynomials, as in  , the algebraic fraction is called a rational fraction (or rational expression). An irrational fraction is one that contains the variable under a fractional exponent, as in

, the algebraic fraction is called a rational fraction (or rational expression). An irrational fraction is one that contains the variable under a fractional exponent, as in  .

.

The terminology used to describe algebraic fractions is similar to that used for ordinary fractions. For example, an algebraic fraction is in lowest terms if the only factor common to the numerator and the denominator is 1. An algebraic fraction whose numerator or denominator, or both, contains a fraction, such as  , is called a complex fraction.

, is called a complex fraction.

Rational numbers are the quotient field of integers. Rational expressions are the quotient field of the polynomials (over some integral domain). Since a coefficient is a polynomial of degree zero, a radical expression such as â2/2 is a rational fraction. Another example (over the reals) is  , the radian measure of a right angle.

, the radian measure of a right angle.

The term partial fraction is used when decomposing rational expressions. The goal is to write the rational expression as the sum of other rational expressions with denominators of lesser degree. For example, the rational expression  can be rewritten as the sum of two fractions:

can be rewritten as the sum of two fractions:  and

and  . This is useful in many areas such as integral calculus and differential equations.

. This is useful in many areas such as integral calculus and differential equations.

Radical expressions

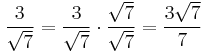

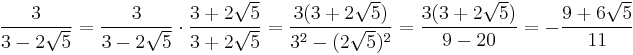

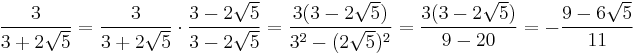

A fraction may also contain radicals in the numerator and/or the denominator. If the denominator contains radicals, it can be helpful to rationalize it (compare Simplified form of a radical expression), especially if further operations, such as adding or comparing that fraction to another, are to be carried out. It is also more convenient if division is to be done manually. When the denominator is a monomial square root, it can be rationalized by multiplying both the top and the bottom of the fraction by the denominator:

The process of rationalization of binomial denominators involves multiplying the top and the bottom of a fraction by the conjugate of the denominator so that the denominator becomes a rational number. For example:

Even if this process results in the numerator being irrational, like in the examples above, the process may still facilitate subsequent manipulations by reducing the number of irrationals one has to work with in the denominator.

Pedagogical tools

In primary schools, fractions have been demonstrated through Cuisenaire rods, fraction bars, fraction strips, fraction circles, paper (for folding or cutting), pattern blocks, pie-shaped pieces, plastic rectangles, grid paper, dot paper, geoboards, counters and computer software.

Pronunciation and spelling

When reading fractions, it is customary in English to pronounce the denominator using ordinal nomenclature, as in "fifths" for fractions with a 5 in the denominator. Thus, for 3/5, we would say "three fifths" and for 5/32, we would say "five thirty-seconds." This generally applies to whole number denominators greater than 2, though large denominators that are not powers of ten are often read using the cardinal number. Thus: 1/123 could be read "one one hundred twenty-third" but is often read "one over one hundred twenty-three". In contrast, because one million is a power of ten 1/1,000,000 is commonly read "one millionth" or "one one millionth". The table could be continued indefinitely.

The denominators 1, 2 and 4 are special cases. The fraction 3/1 can be read "three wholes". The fraction 3/2 is usually read "three halfs" or "three halves", never "three seconds". The fraction 3/4 can be read either "three fourths" or "three quarters".

| Denominator | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| in words | half (or halves) |

third(s) | fourth(s) or quarter(s) |

fifth(s) | sixth(s) | seventh(s) | eighth(s) | ninth(s) |

| Denominator | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

| in words | tenth(s) | eleventh(s) | twelfth(s) | thirteenth(s) | fourteenth(s) | fifteenth(s) | sixteenth(s) | |

| Denominator | 100 | 1,000 | 1,000,000 | |||||

| in words | hundredth(s) | thousandth(s) | millionth(s) |

History

The earliest fractions were reciprocals of integers: ancient symbols representing one part of two, one part of three, one part of four, and so on.[10] The Egyptians used Egyptian fractions ca. 1000 BC. About 4,000 years ago Egyptians divided with fractions using slightly different methods. They used least common multiples with unit fractions. Their methods gave the same answer as modern methods.[11] The Egyptians also had a different notation for dyadic fractions in the Akhmim Wooden Tablet and several Rhind Mathematical Papyrus problems.

The Greeks used unit fractions and later continued fractions and followers of the Greek philosopher Pythagoras, ca. 530 BC, discovered that the square root of two cannot be expressed as a fraction. In 150 BC Jain mathematicians in India wrote the "Sthananga Sutra", which contains work on the theory of numbers, arithmetical operations, operations with fractions.

In Sanskrit literature, fractions, or rational numbers were always expressed by an integer followed by a fraction. When the integer is written on a line, the fraction is placed below it and is itself written on two lines, the numerator called amsa part on the first line, the denominator called cheda âdivisorâ on the second below. If the fraction is written without any particular additional sign, one understands that it is added to the integer above it. If it is marked by a small circle or a cross (the shape of the âplusâ sign in the West) placed on its right, one understands that it is subtracted from the integer. For example, Bhaskara I writes[12]

६ १ २ १ १ १० ४ ५ ९

That is,

6 1 2 1 1 1० 4 5 9

to denote 6+1/4, 1+1/5, and 2â1/9

Al-HassÄr, a Muslim mathematician from Fez, Morocco specializing in Islamic inheritance jurisprudence during the 12th century, first mentions the use of a fractional bar, where numerators and denominators are separated by a horizontal bar. In his discussion he writes, "..., for example, if you are told to write three-fifths and a third of a fifth, write thus,  ." [13] This same fractional notation appears soon after in the work of Leonardo Fibonacci in the 13th century.[14]

." [13] This same fractional notation appears soon after in the work of Leonardo Fibonacci in the 13th century.[14]

In discussing the origins of decimal fractions, Dirk Jan Struik states that (p. 7):[15]

"The introduction of decimal fractions as a common computational practice can be dated back to the Flemish pamphlet De Thiende, published at Leyden in 1585, together with a French translation, La Disme, by the Flemish mathematician Simon Stevin (1548-1620), then settled in the Northern Netherlands. It is true that decimal fractions were used by the Chinese many centuries before Stevin and that the Persian astronomer Al-KÄshÄ« used both decimal and sexagesimal fractions with great ease in his Key to arithmetic (Samarkand, early fifteenth century).[16]"

While the Persian mathematician JamshÄ«d al-KÄshÄ« claimed to have discovered decimal fractions himself in the 15th century, J. Lennart Berggren notes that he was mistaken, as decimal fractions were first used five centuries before him by the Baghdadi mathematician Abu'l-Hasan al-Uqlidisi as early as the 10th century.[17] [18]

See also

References

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W., "Common Fraction" from MathWorld.

- ^ Galen, Leslie Blackwell (March 2004), "Putting Fractions in Their Place", American Mathematical Monthly 111 (3), http://www.integretechpub.com/research/papers/monthly238-242.pdf

- ^ World Wide Words: Vulgar fractions

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W., "Improper Fraction" from MathWorld.

- ^ Math Forum - Ask Dr. Math:Can Negative Fractions Also Be Proper or Improper?

- ^ New England Compact Math Resources

- ^ a b Trotter, James (1853). A complete system of arithmetic. p. 65. http://books.google.com/books?id=a0sDAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA65&dq=%2B%22complex+fraction%22+%2B%22compound+fraction%22&hl=sv&ei=kN-6TuKZIITc0QHStb3eCQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=4&ved=0CD4Q6AEwAw#v=onepage&q=%22complex%20fraction%22&f=false.

- ^ a b Barlow, Peter (1814). A new mathematical and philosophical dictionary. http://books.google.com/books?id=BBowAAAAYAAJ&pg=PT329&dq=%2B%22complex+fraction%22+%2B%22compound+fraction%22&hl=sv&ei=kN-6TuKZIITc0QHStb3eCQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=10&ved=0CFwQ6AEwCQ#v=onepage&q=%2B%22complex%20fraction%22%20%2B%22compound%20fraction%22&f=false.

- ^ http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php/Fraction

- ^ Eves, Howard ; with cultural connections by Jamie H. (1990). An introduction to the history of mathematics (6th ed. ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders College Pub.. ISBN 0030295580.

- ^ Milo Gardner (December 19, 2005). "Math History". http://egyptianmath.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2006-01-18. See for examples and an explanation.

- ^ (Filliozat 2004, p. 152)

- ^ Cajori, Florian (1928), A History of Mathematical Notations (Vol.1), La Salle, Illinois: The Open Court Publishing Company pg. 269.

- ^ (Cajori 1928, pg.89)

- ^ D.J. Struik, A Source Book in Mathematics 1200-1800 (Princeton University Press, New Jersey, 1986). ISBN 0-691-02397-2

- ^ P. Luckey, Die Rechenkunst bei ÄamÅ¡Ä«d b. Mas'Å«d al-KÄÅ¡Ä« (Steiner, Wiesbaden, 1951).

- ^ Berggren, J. Lennart (2007). "Mathematics in Medieval Islam". The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A Sourcebook. Princeton University Press. p. 518. ISBN 9780691114859.

- ^ While there is some disagreement among history of mathematics scholars as to the primacy of al-Uqlidisi's contribution, there is no question as to his major contribution to the concept of decimal fractions. [1] "MacTutor's al-Uqlidisi biography". Retrieved Nov. 22, 2011.

External links

- "Fraction, arithmetical". The Online Encyclopaedia of Mathematics. http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php/Fraction.

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Fraction" from MathWorld.

- "Fraction". Encyclopedia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/215508/fraction.

- "Fraction (mathematics)". Citizendium. http://en.citizendium.org/wiki/Fraction_(mathematics).

- "Fraction". PlanetMath. http://planetmath.org/encyclopedia/Fraction.html.